In this issue: Updates on the annual meeting and other events, five book reviews, and reflections on life in apocalyptic times.

Contents

Letter from the President: Nikolaus Wandinger, About Legitimate Concerns

Editor’s Column: Curtis Gruenler, Disconnection and Misconnection

2024 Girard Lecture, Leiden University/online, November 28, 2024

Theology & Peace Quarterly Speaker Series, online, December 5, 2024

Identity in Suspense, December 5-6, 2024, online

COV&R Annual Meeting, Rome, June 4-7, 2025

Mark Anspach, On the Place of Rivalry in a Convivial Society

David Garcia-Ramos Gallego, When the Apocalypse Comes and All You Can Do Is Watch

David Garcia-Ramos Gallego, Cuando llega el apocalipsis y solo puedes mirar

Chelsea Jordan King, COV&R at the American Academy of Religion

Andrew McKenna, The Uses of Idolatry by William T. Cavanaugh

Reginald McGinnis, The War That Must Not Occur by Jean-Pierre Dupuy

Gena St. David, Alterity by Jean-Michel Oughourlian

Curtis Gruenler, The Brain and the Spirit by Gena St. David

Letter from the President

About Legitimate Concerns

Nikolaus Wandinger

Dear COV&R members and friends,

I write this in the days after the U.S. has elected a new president and, in all probability, has given his party a majority in both houses of Congress. As President Trump has appointed three justices to the Supreme Court during his previous term and the court now has a majority favorable to him, this means that the system of checks and balances has tilted enormously towards him: fewer checks and a certain imbalance in his favor. Now, I do not think it my business to comment on the U.S. elections. I am just stating the above fact, and thinking about it reminded me of something I heard in Raymund Schwager’s dogmatic history of the important councils of the first 700 years of the Christian church, which I think might be interesting for you, Bulletin readers, in the current situation in the U.S. and in many places of this planet where violent conflicts abound.

The councils I am referring to laid the foundation for the church’s deeper understanding of who Jesus Christ was to Christians. They tried to express the seemingly simple article of faith that Jesus Christ was true God and true human in a detailed philosophical terminology that could better explain what this faith meant, what it entailed and what it didn’t entail. I will not go into the specifics here, as you did not sign up for a theology lecture. I want to emphasize, however, that these councils—and especially the developments that occurred in between—were not just instances of peaceful debate. Diverging theological convictions clashed with each other, intermingled with personal or regional animosities and rivalries, and amalgamated with desires for political or ecclesial power and influence. The emperor, bishops and theologians, the Roman Pope, and many others were involved in this fight, which also led to expulsions, excommunications, and even severe bodily mutilation as punishment leading to the death of the theologian Maximus Confessor (†662). He suffered this because he refused to follow an order of the emperor in matters of faith, something which the existing Constantinian form of church demanded. Yet not much later, Maximus’s position shaped the official teaching of the church at the last of the councils I have in mind (Constantinople III in 680/81). The first one is the Council of Nicea (325), whose 1,700 jubilee will be celebrated next year, which was led by Emperor Constantine himself. Maximus’s fate is just one further instance of the problematic of a Constantinian Church, which Wolfgang Palaver described so well in last August’s Bulletin.

Here I want to emphasize something else, however. Despite the fact that these discussions and quarrels were shaped considerably by highly problematic mimetic mechanisms, Raymund Schwager insists, there were also diverging genuine theological concerns that were part of the motivation of the opponents. Human motivation often is permeated by many motives that intertwine, and only a small section of them is known to us; the mimetically induced desires for prevalence and status, especially, often remain unnoticed. Yet they often override those motivations that are conscious and are named as one’s main intentions: the right conviction about the problem at hand—in the case of the councils, how to verbalize the Christian faith about the Christ properly. Nevertheless, at certain points in this process that went on for centuries, a solution was possible that enabled the church to formulate that faith in terms that endured, what we call today “dogmas.”

Schwager claims that this happened because important participants at certain points were able, despite all the mimetic mechanisms going on, to see that their opponent had a legitimate and justified concern, and they tried to incorporate that concern into the formulation they propounded.

Incorporating the legitimate and justified concern of the opponent enabled a good compromise, reconciliation, valid expression of the truth sought, and a way forward out of a situation where it had previously seemed there was no way out. Unfortunately, in many cases, it still was not possible to achieve that without a scapegoat: two opponents or opposing groups found a common ground by incorporating each other’s legitimate concern while at the same time excluding someone whose concern seemed illegitimate to them. Apparently this was the price paid to the mimetic mechanisms involved.

Let us leave the first millennium and theology, and let us travel back to our present day and our torn societies. Couldn’t a lot be won if opponents realized and accepted that the opposing party also has a legitimate and justified concern and tried to incorporate it into their own thinking and acting? Many wars fought on this planet, and many hardened controversies between political foes, might be mitigated or even overcome if this were possible. I spare you an enumeration of examples, as you certainly can find them for yourselves. There is still the danger that this would succeed only by scapegoating a third party; and there might be cases where no legitimate concern can be envisioned—not to speak of the problem of who is to decide when a concern is legitimate and when not.

Still, the readiness to accept that an opponent might have a legitimate concern and the willingness to see it and to integrate it into one’s own conviction might save us a lot of trouble. And it might work as an alternative to the usual checks and balances, one not based on mere power but on the willingness to see the real concerns behind certain diverging convictions. This, then, would distinguish good compromises from bad ones: it is not just about “I give you something, if you give something else to me,” with no connection between the different subject matters. Rather it is, “I see that you have a point; if you can see my point, we might reach a solution that captures the truth better than either of us on our own could.”

Editor’s Column

Disconnection and Misconnection

Curtis Gruenler

René Girard’s apocalyptic strain is good for a glass-half-full person like me. Mimetic theory helps me make some sense of the darkness in humanity rather than just looking away.

The election of Donald Trump supplies a lot to look away from. And there may be some discipline in looking away from his scandalous flaunting of power, elevating clowns and taunting opponents—scandalous in the Girardian sense of inciting rivalry and, especially in his case, coercing from us the prize he seems most to desire, the coin of our media-saturated age, attention. So enough about him.

Apocalypse means revelation. What is revealed in recent turns of the political wheels of fortune? My sense is that the U.S. election underscores the abysmal disconnection suffered by most of the electorate. The results of the American Enterprise Institute’s 2024 American Social Capital Survey show substantial losses of social connection by every measure and across every demographic, with markedly greater losses among the less educated. The education gap also emerged as a major story in polling on the presidential election, with more educated voters, who are thus likely to be less disconnected, favoring Kamala Harris.

Disconnection, I suspect, makes people more prone to resentment, delusion, and everything that Dostoevsky already portrayed two centuries ago in Notes from Underground, now exacerbated by the swirl of electronic media beaming mash-ups of truth and falsehood, formatted to induce feelings of pseudo-connection, into everyone’s personal cave.

Perhaps it would be better to say, though, from a mimetic perspective, that, except in extreme cases, disconnection is not as accurate a diagnosis as misconnection. To be human is to be relationally connected, for both good and ill. This diagnosis implies a cure: better connections.

Robert D. Putnam’s influential book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000) and his more recent The Upswing: How American Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again (with Shaylyn Romney Garrett, 2020) renewed the argument that social and political health depend on good interpersonal connections. Putnam’s work inspired the documentary Join or Die, winner of the 2024 unRival Award at last winter’s Justice Film Festival. It is available on Netflix as well as for community screenings.

My favorite source for an encouraging perspective on what is happening Stateside under the radar of the dominant media, and what individuals can do, is James Fallows, dean of American journalists. He recently announced that on his Substack, Breaking the News, he will be keeping “an informal running list, updated and loosely categorized, of the ideas and possibilities for civic harmony, progress, and re-connection that people are discovering, and where and how these are paying off.”

More theoretically, Hartmut Rosa’s Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World, which I first heard of at COV&R’s annual meeting this past summer, makes a major contribution to understanding our current conditions of alienation and theorizing its opposite, for which he uses the metaphor of resonance in ways I find strongly compatible with mimetic theory. Rosa mentions the Second Convivialist Manifesto, discussed elsewhere in this issue by Mark Anspach, as a framework for a political and economic order that would help cultivate resonance and what I would call positive or loving or creative mimesis.

Calling mimesis creative recognizes the need for imagination. Misconnection and the social structures that promote it are familiar and, in that sense, easy. I wonder if the inability to imagine healthy connections, especially beyond one’s own, like-minded circle, is another thing revealed by recent elections. Envisioning a politics that rises above an us-against-them, zero-sum attitude, and trusting someone who tries to articulate one, requires imagination. Every healthy connection we make not only opens one more potential friendship but also, no matter how far it goes, plants a seed for imagining a world built of such connections. This, at least, is my glass half full of water for such seeds.

News

I was delighted to host Sam Sorich, director of the award-winning, feature-length documentary Things Hidden: The Life and Legacy of René Girard, for a screening at Hope College’s Knickerbocker Theatre, the last in a multistate swing of screenings during the month of November. The film will be released later this year. To see a trailer and sign up to receive updates about the film, go to https://www.thingshidden.movie/.

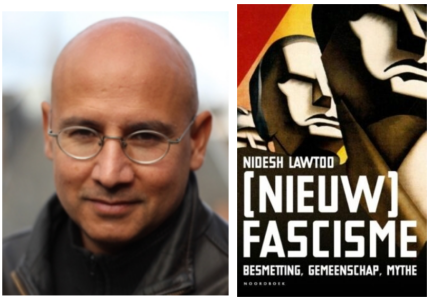

Nidesh Lawtoo will give the 2024 Girard Lecture addressing “The Urgency of Mimetic Studies: From Imitation to (New) Fascism” on Thursday, November 28, 17:15-18:30 CET. It’s a hybrid event, with a ZOOM link available here. More information about the lecture is available here. Two books edited by Lawtoo in conjunction with the Homo Mimeticus research program have recently appeared: Homo Mimeticus II: Re-Turns to Mimesis, co-edited with Marina Garcia Granero, and Mimetic Posthumanism: Homo Mimeticus 2.0 in Art, Philosophy and Technics.

The Call for Papers for COV&R’s annual meeting next year in Rome is available on the conference website. For more information, see the announcement below.

The Interdisciplinary Journal of Mimetic Theory, Xiphias Gladius, has published a new issue with articles on mimetic theory and phenomenology. The next issue will be a tribute occasioned by the passing of former COV&R president Cesáreo Bandera. A call for papers is available here. Submissions are due March 15, 2025.

Congratulations to Chelsea Jordan King, coordinator of COV&R’s sessions at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion (see her report below), on the publication of her new book, Reclaiming Sacrifice: Integrating Girardian and Feminist Insights on the Cross. For more information, see the publisher’s website.

The French blog Emissaire has been publishing weekly Girardian commentaries on a wide range of topics. A recent one, for instance, addresses the problem of the sacrificial nature of institutions through the example of school.

A 20% discount is available to COV&R members on the nine most recent books in Studies in Violence, Mimesis & Culture and Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory, including the four out this year: The World of René Girard, interviews conducted by Nadine Dormoy in 1988 and translated from French by William Johnsen; Cormac McCarthy: An American Apocalypse by Marcus Wierschem; René Girard and the Western Philosophical Tradition, Volume 1: Philosophy, Violence, and Mimesis, edited by Andreas Wilmes and George A. Dunn; and Playing Sociology: Theory and Games for Coping with Mimetic Crisis and Social Conflict by Martino Doni and Stefano Tomelleri. In addition, a 30% discount is available on selected titles from the backlist with a purchase of three or more. For more information, please see this page in the members section of the COV&R website. The same page includes a discount code for ordering through Eurospan, which has better shipping rates when ordering from Europe than ordering directly through MSUP.

The partial directory of COV&R members initiated by Mack Stirling earlier this year was updated this fall. This link will take you to a page where you can enter your member number to download the directory as either a pdf document or an Excel spreadsheet. The same page has a link to submit your information for inclusion in the next update. For questions about your membership or access to the member pages on the website—or to join COV&R—see our membership services page.

Julie and Tom Shinnick’s read-aloud-and-discuss Zoom group is working through Tony Bartlett’s Signs of Change: The Bible’s Evolution of Divine Nonviolence (reviewed in Bulletin 72 by Scott Cowdell and by yours truly here). It meets weekly on Monday nights at 6:30-8:00 Central Time. New participants are welcome. As Julie puts it, “The read-aloud format provides an opportunity for rich discussion which members have greatly appreciated. It also helps readers and listeners slow down from our busy lives for a weekly period of reflection in a small community. We only read 10-20 pages a week, so it is easy to catch up if people have to miss a session or two. We record each session for anyone who misses a meeting and wants a copy. The recordings are private, and only sent to members who request them. About a week before the meeting I’ll send out a link for the zoom.” If you are interested, please email Julie.

Forthcoming Events

2024 Girard Lecture of the Dutch Girard Society

The Urgency of Mimetic Studies: From Imitation to (New) Fascism

Leiden University/online

November 28, 2024

17:15-18:30pm CET

Nidesh Lawtoo will deliver the fifth Girard Lecture sponsored by the Dutch Girard Society. More information is available here, with the Zoom link for the lecture available here.

Nidesh is making available for download the chapter “Trump and Contagion” from (New) Fascism.

Theology & Peace Quarterly Speaker Series

The Wicked Truth: When Good People Do Bad Things

Online

Thursday, December 5, 2024

7:30-9:00pm EST

A long-anticipated film adaptation of the musical Wicked will be in theaters on Thanksgiving weekend! In conjunction with Wicked’s premiere, the Theology and Peace Quarterly Speaker Series is delighted to host Suzanne Ross, author of The Wicked Truth: When Good People Do Bad Things, which dissects Wicked’s remarkably enduring plot line from the perspective of Rene Girard’s mimetic theory.

Wicked is a radical reimagining of the classic tale The Wizard of Oz, and has played for 21 years on Broadway. Audiences don’t connect with Wicked because it presents a fantasy land utterly unlike their own. Rather, people return to this story because it depicts interpersonal relationships and societal patterns that are intimately familiar, ones exploring the very notion of good and evil. As the composer and lyricist Stephen Schwartz, puts it, “[Ross’s book] is a fascinating and valuable study of the ways we all wrestle with the wickedness within and without us….” Ross’s interview with Wicked composer and lyricist Stephen Schwartz is available here.

Registration for the lecture is free. For more information, click here.

Identity in Suspense

Political and Aesthetic Articulations of Alterity

Viewed from Mimetic Theory and Psychoanalysis

Online

December 5-6, 2024

This conference, sponsored by the Critical Thinking and Subjectivity Research Group at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogatá, is an invitation to reflect on politics and art, putting the notion of identity in doubt to illuminate the intersubjective and relational environments in which it acquires consistency and meaning. A common trait between psychoanalysis and mimetic theory is their suspicion of a sovereign subject. Being is being for another—or through another—who could be the father or the Girardian mediator; nevertheless, the sense of self is always in relation to another. The task is to ask ourselves about the relation rather than the content: How is identity assumed in the commodified relational environment of late capitalism? How is identity articulated in the state of war of the contemporary world? Are there post-anthropocentric identities at the brink of climatic catastrophe? Is violence a generative principle of identity? Can art put identities in disarray to open up non-sacrificial spaces?

We want to dialogue with philosophy, humanities, psychology, psychoanalysis, and social sciences, as well as with decolonial positions. We believe that mimetic theory invites us to study and propose different approaches that help to think about identity, its relationship with the contemporary world, with violence among others. This is the reason why we have invited people from different fields of knowledge to participate in this meeting, always in reference to the mimetic theory as proposed by René Girard, and with the aim of having serious conversations that seek better understandings and solutions to the current crisis.

The conference will be held on Zoom; here is the link to join. Further information, including the schedule, will be announced on Instagram here.

Spirituality, Religion, and the Sacred

COV&R Annual Meeting

Rome

June 4-7, 2025

The conference explores the parallel growth of individualistic spirituality and the violent sacred within an increasingly polarized world. The apparent modern contradiction—between religion and spirituality, accompanied by increasing individualization, polarization and dangerous collective behavior—can be helpfully understood in the light of René Girard’s analysis of modernity and the foundational and regulative function of religion, along with his critique of a newly emerging post-secular sacred. The aim of the conference is to examine the foundational—though often unexamined or misunderstood—dynamics of our time in which the sacred and religion play a fundamental role. The conference’s theme re-considers who we are—and might become—as homo mimeticus/religiosus, seeking a new reading of our unique historical moment, and how we have emerged into it.

The conference is open to academics, professionals, practitioners in the field, and anyone interested in the conference topic or René Girard’s mimetic theory.

The conference will explore these themes with some ground-breaking speakers and panels.

- Prof. Ann Astell (University of Notre Dame, USA), Rev. Prof. Tomáš Halík (Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic) and Assoc. Prof. Brian Robinette (Boston College, USA) will break open key themes around “religion, spirituality and the sacred in modernity.”

- Prof. William T. Cavanaugh (De Paul University, Chicago, USA) will trace the migration of the sacred and identify modern forms of idolatry. His recent book The Uses of Idolatry (Oxford University Press) is reviewed by Andrew McKenna elsewhere in this issue.

- Assoc. Prof. Diego Bubbio (University of Turin, Italy) will speak as part of a panel on “The ‘self’ and spirituality now and then.”

- The final day will include a discussion forum on the conference theme, with reflections from the conference organizers: Prof. Scott Cowdell (Charles Sturt University), Assoc. Prof. Chris Fleming (Western Sydney University) and Assoc. Prof. Joel Hodge (Australian Catholic University).

Further speakers and panels will be announced in the new year.

The call for papers and information about the Raymund Schwager Memorial Essay Contest and travel grants are below. Registration details and information about accommodations will also be announced on the conference website soon.

The campus is located centrally in the suburb of Trastevere, with a range of hotels and restaurants nearby. There will be meals and some accommodation available on campus.

For more information about the conference, please contact Joel Hodge.

Call for Papers

Paper proposals and panels from any field of study are welcome, particularly as they relate to the conference theme. As the aim of the Colloquium is to explore, criticize, and develop the mimetic model of the relationship between violence and religion in the genesis and maintenance of culture and as the Colloquium is concerned with questions of both research and application, we welcome papers related to all aspects of mimetic theory. The conference is open to academics, professionals, practitioners in the field, and anyone interested in the conference topic or René Girard’s mimetic theory.

Proposals should contain your name, affiliation, the title of the paper, and an abstract of the planned paper of about 200 words. All submissions should include a statement at the end of the proposal listing technology needs. If needs are not stated at the time of submission, the host institution may be unable to accommodate them.

Papers are to be of a length for a 20-minute presentation, with 10 minutes for questions and discussion. Panels (of 90 minutes with 3 papers) on a particular theme are also welcome.

If you are a graduate student and your proposal has been accepted, there is the possibility of applying for the Raymund Schwager, SJ, Memorial Essay Contest.

Workshop Proposals

The organizing committee also welcomes proposals for practitioner-focused, interactive workshops that relate to the work of Girard or the conference theme. Such sessions could take different forms (e.g., workshop-style, forum, discussion group, panel) and may cover areas such as spirituality, peace-building, inter-faith dialogue, Girard and preaching, or Girard and psychotherapy (not an exhaustive list). Please provide a description and rationale for an inter-active workshop on a particular topic to be facilitated for approx. 45 or 90 minutes by appropriately qualified persons.

There will be two rounds of proposals (to assist those with planning and funding requirements). Responses will be given shortly after each due date. For more information or to send a proposal (including a title, 200-word abstract and contact details), please email the conference organizers at joel.hodge@acu.edu.au and info@australiangirardseminar.org by 15th December 2024 (for the first round). For the second round, please send your proposal by 15th April, 2025.

Raymund Schwager Memorial Essay Contest

To honor the memory of Raymund Schwager, SJ, the Colloquium on Violence and Religion is offering an award of $1,500 shared by up to three persons for the three best papers given by graduate students at the COV&R 2025 meeting at the Australian Catholic University. Receiving the award also entails the refund of the conference registration fee—this should be factored in the calculation of the conference fee.

Students presenting papers at the conference are invited to apply for the Raymund Schwager Memorial Award by sending a letter to that effect and the full text of their paper in an e-mail attachment to Joel Hodge, organizer of the COV&R 2025 meeting and chair of the three-person COV&R Awards Committee. The paper should be in English. The paper should be 2500 words, double-spaced-12-point font excluding notes. That should work out to a 10-page text excluding notes that can be read in 20 minutes. Because of blind review, the author name should not be stated in the essay or in the title of the WORD file. Due date for submission is 1 May 2025. Winners will be announced in the conference program. Prize-winning essays should reflect an engagement with mimetic theory; they will be presented in a plenary session and be considered for publication in Contagion.

Travel Grants

COV&R offers a limited number of travel grants for grad students or practitioners of mimetic theory (e.g., NGO/non-profit staff; journalists, government employees). Preference is given to graduate students but practitioners of mimetic theory are also encouraged to apply.

In order to be eligible you need:

- to have an accepted paper proposal and offer a presentation at the conference

- to have not received the travel grant previously

- to belong to the groups mentioned above.

To apply for a travel grant: send your confirmation of acceptance at the conference and your situation to the COV&R executive secretary, Joel Hodge.

COV&R travel grants are for cost of transportation only and are at a maximum of $US1,000 per person. If your travel costs are less, you will receive the actual cost of travel. If your travel costs exceed that amount, you will have to finance the excess yourself. The travel grant money will be awarded after the conference. Recipients’ conference registration fee will also be refunded.

Commentary

On the Place of Rivalry in a Convivial Society

Mark Anspach

We live in a time of political crisis when the ideologies that dominated the 19th and 20th centuries have run out of steam. Another world is surely possible, but what should that world look like? Critics of the society in which we live are legion, yet there is a dearth of overarching alternative visions.

Girardian theorists cannot look to René Girard himself for guidance in this regard. He proposed far-reaching hypotheses about the origin and function of political institutions but refrained from offering concrete prescriptions as to how existing institutions might be improved. This is a strength as much as a weakness. It means that individuals of varying political outlooks may work together to develop the theory without getting caught up in the partisan rivalries that might otherwise divide us. (On the status of the political in Girard’s thought, see the remarkable dossier René Girard politique in Cités 53, 2013.)

If there is one thing on which Girardians of every political stripe can agree, it is on the omnipresence of rivalry. How to deal with this phenomenon is one of the most salient points of contention between the political ideologies of the past. Collectivist ideologies sought to abolish the human propensity to rivalry and ended up sacrificing individual freedom and initiative; liberal individualism gave rivalry free reign at the risk of losing a shared sense of commitment to the collective good. Is it possible to imagine another path, one more faithful to our dual nature as creatures whose egoism and sociality are inextricably intertwined?

Enter the Convivialist movement. The guiding spirit behind this movement is French sociologist Alain Caillé, who, more than 40 years ago, was the chief founder of the Mouvement Anti-Utilitariste dans les Sciences Sociales (of which I am a longtime member). The utilitarianism it targets is less the philosophical school of Bentham and Mill than the relentlessly materialist economistic thinking common to vulgar Marxists and neoliberals alike. The acronym MAUSS is a tribute to Marcel Mauss, author of the pioneering study The Gift (HAU Books, 2016). Mauss insists that givers of gifts are motivated by individual self-interest and social obligation all at once. Gift exchange is, he shows, a universal practice in human societies, more fundamental than market exchange.

By spurring individuals to outdo each other in generosity, gift exchange gives premodern societies a way to channel antagonisms and rivalry into positive reciprocity (see Mark R. Anspach, Vengeance in Reverse: The Tangled Loops of Violence, Myth, and Madness, and my contribution to the Palgrave Handbook of Mimetic Theory and Religion, Vengeance and the Gift). So it is, Mauss concludes, that “the clan, the tribe, and the peoples have learned—as, tomorrow, in our so-called civilized world, classes and nations and individuals too will have to learn—how to confront one another without massacring each other, and to give to each other without sacrificing themselves to the other” (p. 197).

The MAUSS is still going strong today. It is itself a convivial group that, like COV&R, is unusual not only in being interdisciplinary but in bringing together individuals from both inside and outside academia. In addition to its semiannual journal in French, the Revue du MAUSS, now edited by Philippe Chanial, the organization recently inaugurated an annual electronic journal in English, MAUSS International. Meanwhile, Caillé launched the parallel Convivialist movement in an effort to translate the MAUSS’s theoretical ideas into more concrete political form.

The first Convivialist Manifesto, subtitled A Declaration of Interdependence, was originally published in French in 2013. Echoing Marcel Mauss, it defines convivialism as “a mode of living together (con-vivere) that values human relationships and cooperation and enables us to challenge one another without resorting to mutual slaughter.” The manifesto is noteworthy in its realistic approach to conflict: “To try to build a society where there is no conflict between groups and individuals would be not just delusory but disastrous. Conflict is a necessary and natural part of every society” (p. 25).

A healthy society must “foster an attitude of cooperative openness to the other” and accommodate diversity while insuring that “this plurality does not turn into a war of all against all.” The objective is to “make conflict a force for life rather than a force for death” and “turn rivalry into a means of cooperation, a weapon with which to ward off violence” (ibid.).

By the same token, a healthy society must “satisfy each individual’s desire for recognition” while preventing that desire “from degenerating into excess and hubris” (ibid.). Does this mean that the good convivial citizen must lead a subdued, sober, quiet little life, doggedly avoiding every form of excess? No, responds François Gauthier in a special issue of the Revue du MAUSS entitled “Demain, un monde convivialiste.” The agonistic dimensions of politics, sports and culture are “fundamental ritualities through which excess may be expressed” (Gauthier, “Réguler l’hubris: Quelle hubris?” in Revue du MAUSS 57 [2021], p. 57).

Like conflict, hubris is “necessary and constitutive, but its manifestations must be submitted in the last analysis to the principle of conviviality”: they must promote the social bond (Gauthier, p. 58). As Frank Adloff notes in his introduction to the manifesto (p. 7), the theme of regulating hubris goes back to Ivan Illich’s 1973 book Tools for Conviviality. For Illich, a convivial society is one that imposes constraints on the technological and institutional tools we use so that they work for us rather than making us work for them.

The foregoing quotes will be resonant for many COV&R members. They may serve to introduce the following excerpts from the Second Convivialist Manifesto (2020). Subtitled Towards a Post-Neoliberal World, this new document was originally published in French and signed by some 300 intellectuals from 33 different countries. (The Convivialism website features links to the second manifesto in French, English, German, Italian, Catalan, Portuguese and Arabic.) The reproduction of parts of the manifesto here does not imply endorsement, nor do the excerpts chosen fully encapsulate the text as a whole. Rather, these passages tackle questions of special interest to COV&R in a way that may offer a welcome stimulus to our own thinking.

* * *

The Second Convivialist Manifesto (excerpts)

This text is reprinted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0). It is drawn from the abridged English version published in the open-access journal Civic Sociology 1, 1 (2020).

Because everyone is called upon to express their singular individuality, it is normal for humans to be in opposition with each other. But it is only legitimate for them to do so as long as this does not endanger the framework of common humanity [“there exists only one humanity”], common sociality [“human beings are social beings”], and common naturality [“humans do not live outside nature”] that makes rivalry fertile and not destructive. Politics inspired by convivialism is therefore politics that allows human beings to differentiate themselves by engaging in peaceful and deliberative rivalry for the common good…

The first condition for rivalry to serve the common good is that it be devoid of desire for omnipotence, excess, hubris (and a fortiori pleonexia, the desire to possess ever more). On this condition, it becomes rivalry to cooperate better…

All [modern political] ideologies, to varying degrees, share the same limitation: because they assume that humans are first and foremost (if not exclusively) needy beings, they deduce that the cause of the conflict between them is material scarcity.

And there is, of course, some truth in that. But this need is inseparable from the desire for recognition. While all the material needs of infants deprived of their mothers can be met, if they do not also receive love, if they are not recognized in their uniqueness, they will die or fail to develop.

Hoping to satisfy all needs is a recipe for disappointment simply because a need is always recharged and sharpened by desire. If this desire is not both satisfied (by affection, respect, or esteem) and limited by prohibitions that prevent it from degenerating into hubris, then needs become insatiable, whatever the level of wealth reached.

By reducing the political problem to the satisfaction of needs, and in particular material needs, the classical discourses of democratic modernity are proving to be constitutively incapable of addressing the crucial problem of humanity. A problem that is both psychological and political, individual and collective. At the collective level, these classical discourses are lost because they are unable to answer the question of how to limit the aspiration to the omnipotence of the “Great Ones,” “who wish to command and oppress” (to paraphrase Machiavelli); how to control the hubris inherent in human desire when nothing channels it. The hubris of the Greats can trigger by mimicry and envy that of the “Little Ones,” or their resentment.

It can now be said with certainty that to satisfy needs made insatiable by unlimited desire, it has been necessary to form a “master and possessor” relationship with nature, and abandon the former relationship of gift/counter-gift with it, a reciprocal relationship in which one cannot take without giving back, even if only symbolically. But nature has its limits, and these have clearly been reached by now. Nature has already given (or, rather, let be taken) a good part of what can be given without return. And without receiving the attention she deserves, Gaia takes revenge. Hence, as political ecology has long made clear, we need to affirm through the principle of common naturality that our fate is linked to nature’s destiny, that we are interdependent, and that by exhausting nature, it is our very survival that we are gravely endangering. To be sure, political ecology has become the fifth and most recent discourse of modernity. Whilst the most precious, perhaps, it nevertheless still lacks the ability to specify its relationship to our inherited ideologies.

The metaprinciple of hubris control, so well highlighted by the ancient Greeks, formulates the central problem that humanity must now tackle resolutely. Unless humanity agrees on a virtue for which it is worthwhile to restrain the potential limitlessness of desire, and concur on how to run it out of steam, humanity will perish. Indeed, the primary social and political role of religions has been precisely that: to curb the desire of omnipotence, of the “Great” and the “Little,” by trying to subject everyone to a transcendental law, to heteronomy, by allowing hopes of reward—for those who could resist insatiable desire—or threatening those who would yield to it with afterlife punishment.

The problem with the discourses of modern democracy is that they are unable to block limitless desire. Their greatness resided in the promise of emancipation—in other words, in the affirmation that individuation, subjectification, becoming a subject are possibilities offered to all. Yes, they say, it is possible, necessary, desirable to “get out of the state of minority,” out of heteronomy, and to free oneself from the domination of the Great Ones. Yet most often, in the final analysis, these discourses hardly manage to conceptualise emancipation as different from surrender to an attitude resembling the hubris of the Great, each reproducing it in their own creed, in a way that everyone ceases to be servant and all become masters. This does not solve the hubris problem at all. Neither collectively nor individually.

How, then, to convince “modern” nonbelievers—especially when they no longer believe in “secular religions,” like communism, the republic, socialism, progress, and so on—to renounce the hubris, the infantile desire for omnipotence, if they no longer expect any reward or fear any punishment in the afterlife? Why, in the name of what, should they give up their desire to dominate those they have the power to dominate? The answer is that by violating the principles of common humanity, common sociality, common naturality, legitimate individuation for all, and creative opposition, they endanger the very survival of humanity and expose themselves to legitimate anger and contempt and stigma from all. This just anger must not be transformed into hatred and resentment, lest a toxic hubris be overtaken by an even more devastating one.

Under the reign of neoliberalism and rentier and speculative capitalism, the only outlasting value has been market wealth. In the dominant thought, only those who gain access to the power of money are considered worthy of recognition. This has replaced mutual trust with mutual distrust. On the contrary, in a convivial society, the actions that will be valued first and foremost are those that ensure respect for the principle of common humanity, contribute to more harmonious social relations, preserve the natural environment, and are deployed in art, science, technology, sport, democratic inventiveness, convivial attitudes, etc. Convivialism is above all a movement to invalidate that dominant value that prevails today.

Letter from…Valencia, Spain

When the Apocalypse Comes and All You Can Do Is Watch:

Reflections on the Images of a Tragedy

David Garcia-Ramos Gallego

When one experiences a catastrophe at close quarters, one is struck by a feeling of reverie and unreality, an uneasiness that is difficult to explain: horror, anguish, bewilderment, confusion, rage. It is as if when the end of the world comes—at least the end of one’s world, of that ensemble of securities on which we move every day—as if when the apocalypse arrives, only the images of destruction and evil were true. Dismay and despair cause us, having abandoned all hope, to enter hell.

On Saturday night I thought about the members of the COV&R and this Bulletin and decided to write to Curtis to propose a few lines about what was happening. It was the early hours of Saturday to Sunday morning, 2 am, in Catarroja, one of the affected areas. The silence was sepulchral and many stars were visible—something rare in the metropolitan area—and piles of mud and piled up cars were like a war film set. From the beginning I had in mind Dupuy’s thoughts on the catastrophe, and the late, and controversial, apocalyptic Girard, and it seemed to me that I could put together some words that might illuminate this landscape from mimetic theory. I was not aware to what extent it would be possible to do so that very Sunday.

Images, Mexican writer Juan Villoro reminds us in a recent essay, are not worth a thousand words. Images say nothing. Images say what they say to us. We have to translate them, put them in context, understand the intention of the author or of the one who uses them without the author’s permission; images thus have several lives. Many friends from all over the world, from Madrid to Aalst, from Mexico to Catania, from New York to Hradec Kralove, from Guam to Santiago de Chile, from Puerto Rico to Padua, have written to me these days worried, frightened by the images. What follows is the beginning of an attempt to think, narratively, about the catastrophe and the apocalypse, from the inside and without the limitations of an academic discourse. It will disappoint almost everyone, starting with me, but it is necessary to recount the images in order to make the images count. Hence, I apologize that there will be only three images.

For what is to be seen is “Eye has not seen, nor ear heard, / Nor have entered into the heart of man.” What is to be seen is the apocalypse.

Day 1. Tuesday, October 29

On Tuesday afternoon the first meteorological alerts began to arrive from the different services and civil authorities in Valencia. In Xàtiva and Alzira classes are suspended, something that is usual, because every year the phenomenon that today we call DANA (a Spanish acronym for high-altitude isolated depression) occurs, but here it has always been called “Gota Fría,” and that every year causes incidents of varying severity. Nobody could imagine what was going to happen. We all act by inertia—mimetic inertia. As I am from Madrid, every year I joke about how nervous Valencians get about “four drops”. I was going to regret those words. Others lock themselves in panic and the more practical ones take the car out of the garage so that, if the water comes in—it does sometimes, 20 or 40 centimeters at most—they don’t get stained. They park them outside, in the higher parts of the city, on bridges, etc. It’s time to go home, after work, classes at the university or shopping at the malls. During all the previous day and this very day it has rained heavily in Valencia and surroundings, but right now it is not raining. We continue our activities normally. Around 5:21 pm, the first problems begin in the subway, and a former student, who was attending a conference on philosophy and cinema at our university, and whom I had not seen for some time, decides to return home before the end of the last lecture. He wants to bring another colleague to his home by car, because they have read on the net that the subway is not working. With a new car that he will lose forever in a few hours in order to save his life. We get home and start listening to the news, but we are not yet able, even seeing images, to imagine the worst that was already happening.

Day 2. Wednesday, October 30

Classes are not going to be suspended until 3:00 pm. We have needed almost 24 hours to assimilate what they tell us. What the witnesses tell us through the images they send us. In a society of instant and image, it is incredible how long it has taken us to respond. In downtown Valencia, just 10 minutes by car from the disaster, nothing has happened. And we act as if nothing had happened, mimetically. We continue with the conference in spite of everything. Although things have already started to happen, we know about them from those who survived, so there are still no victims, only survivors.

Early this morning a colleague went to pick up our former student by motorcycle. He was in a basket pavilion where he was taken by the security forces at 7 am. He has hardly slept and has put on some dry socks that they have given him, but he is still dressed in the same clothes and the same sneakers, which have mud on them. We look at them when he shows them to us. We see without seeing. And we hear without hearing what he tells us. We reflect on the dilemmas—save the car or save his life. He tells us that a woman has stayed in the car. He himself has hesitated: it is only three weeks since he bought it. He walks to a bridge to escape the water current and there a bus driver makes all the passengers get off to go home himself and leave them there. While we are processing all this, we talk about Wim Wenders, Aki Kaurismaki, John Ford, Jean Renoir, Yasujirō Ozu, or Terrence Malick, and the philosophers Stanley Cavell, Gabriel Marcel, or Josep Maria Esquirol. In our questions and interventions, the Event slowly (too slowly!) creeps in. After lunch, a colleague told me that the grandmother of another colleague had passed away. The story is like a horror movie: she was ill and bedridden, the caregivers had raised the bed as much as they could and left to get help that would arrive too late. The horror, the catastrophe, the apocalypse, is revealed in its first form, that of evil, and it does so in images that we have not yet seen—or that we have seen little, as if looking away: the images of the imagination, the images painted in our minds by the words of the survivors, of the witnesses. At the end of the conference, not knowing what to do, we go to dinner. It will be a soup that will later have a bitter aftertaste—not like the soup that Levinas or Esquirol talk about, the one we share at the table with our friends; but like the one from Elie Wiesel’s prison camp, a bitter soup that others, the victims and survivors, will not be able to eat or taste. We speak of projects for the future, of the hope of the hopeless, of the society of the dispossessed and the “on the margins” of Alice Rohrwacher’s films. Without knowing it, the project is taking shape less than 10 minutes away by car, a desolate, macabre, deadly shape.

Day 3. Thursday, October 31

Classes at the university are cancelled all day. The first volunteers begin to arrive and with them come the stories. It is true that we receive terrible images on our smartphones, but it is as if the saturation of images and the adiophorization of evil—of which Bauman speaks—have anesthetized us. They are too similar to other moral evils, those of the war in Gaza or the devastated cities of Ukraine. As if there were an echo between the two images, something secretly connecting them. This day the images have multiplied, but so have the stories. Even though we live in an image culture, we need those images to have meaning—or more meaning than the tourist meaning with which we seem to look at pictures of atrocities or victims, as Susan Sontag pointed out. We need someone to tell us that this image is true, to place it in a network of meanings, in a constellation of meaning, a sort of profane illumination, in Benjamin’s words.

It is at this moment that the first interpretations of these images begin to be produced, to be used in the political arena by those most responsible for the management of the catastrophe: the abandoned cars, piled one on top of the other by the force of the flood, the streets full of mud and dragged objects. Everything begins to form part of the scenery that the media are going to set up so that it reaches everywhere. As always, reality will surpass fiction, not only because the smell will be a slap in the face that wakes us all up from the hallucinated contemplation of the images, but also because we will never be able to separate those images from the people who tell us about them: Juani, Ana, José, Pepe, Lucía, Joan….

In the afternoon we went for a walk with the children and met several families. Nothing is normal, knowing what is happening 10 minutes away by car. We look around us and, by inertia, we continue to act the same way—we go for a walk with the kids, we have a beer, we make plans. But there’s a dissonant note, as if something has happened that we can’t ignore anymore. We begin to feel the guilt of the innocent—we have done nothing, but we are not doing anything either. We are a community of guilty people— just like the community of culprits the Dardenne brothers talk about. In order to found a community of hopefuls it will take just one more day, a second apocalypse, a second revelation. We decided to organize ourselves to go in the morning. We act out of inertia, but sometimes inertia cracks and we let something different, something new break through. We act against inertia, and this also has a mimetic dimension.

A family with children dressed up to celebrate Halloween passes by. We unload our anger on them, we make them guilty: how dare they celebrate, it’s not even a holiday that makes sense to us? That new thing that had begun to form in our way of looking is now looking for culprits to unload on. Someone has to pay for this feeling of impotence and guilt, for so much confusion: let’s make a bonfire to light the way. If necessary, let us burn someone in it. Even if we have to burn also that new thing that was being born in us to get us out of our mimetic inertia.

Day 4. Friday, November 1, All Saints’ Day

We leave at 7 am to avoid traffic jams and to be allowed to pass. We are nervous, we are going to an unknown area. We have seen hundreds of images, but we know that between the image and the experience there is a leap. When we arrive, it is like entering into a Martian space, a space of war, like those spaces in the films of Alice Rohrwacher or Andrei Tarkovski. We look at reality as we look at photos or cinema, a reality already represented. But what we see exceeds and remains small, it is real and unreal. The work is mechanical: removing the mud from the houses, from the churches, from the streets. Opening garages with what you have at hand, a sledgehammer, kicking, with levers, to see if there is someone, to be able to remove the water, the mud, the slime.

The smell when we lift a piece of furniture, with the mud stagnating underneath, hits us and we throw our heads back and cover our faces. We don’t know it yet—we don’t know anything! —but soon we will know that it is due to the decomposition of microorganisms in the stagnant water and, in the worst case, the decomposition of corpses. We still don’t see anyone wearing masks because no one has told them to. We will feel irresponsible for having gone, for having hindered the work of the professionals. They will put fear in our bodies for wanting to go to help the other, the one who has lost everything. For having had an experience of charity, of tzedekah (צְדָקָה), for comforting the orphan, the poor, the stranger and the widow. The belt of towns surrounding Valencia, Catarroja, Massanasa, Alfafar, Sedaví, Albal, Paiporta, Picanya, and others, is working class and migrant, although there are also people with money, who are lifelong locals. Small and medium-sized companies. In general, humble and ordinary people.

Here is the second apocalypse, the second revelation: love is in the heart of man, waterlogged and muddy like the houses we enter asking if we can help. On occasions like this, the good struggles to come out and push us to do the right thing, without looking at what consequences it may have for us, without interest. There is an impressive mimetic pull: from Valencia thousands of people cross the new riverbed to reach the hell of Paiporta, of Catarroja, of Alfafar. The bridge they cross has been baptized in the media as the bridge of hope; others call it the bridge of solidarity. Those of us who, cynical like me, have a certain allergy to the masses, those of us who find it difficult to accept masses of any kind, cannot help but be suspicious of their motives. From the gesture of sanctity of a few—those who decided that there was a lot more to do with heroic passion and burning with charity—those of us who were disoriented have gone out to meet the needy.

At 12 noon the movement of people in the main avenue of Catarroja is too much: we have been five hours almost without stopping even to drink water—we are afraid of running out of it and, worse, leaving the survivors without it. It is overwhelming. Some people take pictures. I have decided to take only a few. I send them by e-mail to a friend, to a colleague who doesn’t know I live in Valencia, to my wife, to my brothers. But I feel bad about doing it. I do not want the image, what I am seeing, to be re-signified, to become a totem and a grail, a sign and a token of new violence. I am not a professional photographer, it is not my job. But even so I have to resist the temptation to take pictures, to do photographic tourism. I am outraged, although I understand the impulse, to see people taking pictures. I think I’m touching on something essential here: why does it outrage me or why, at the very least, do I see it as problematic? With what intention do I take the photo, what do I send it for, to whom do I send it? The factors of reuse and re-signification of the images are there: these images remind me of the images of war, of the flood of ’57 (but colored), of the movies. Juani crying disconsolately at the door of her house reminds me of the images of the mother, of pity, of despair, of the victims: a silent cry. But this pain is concrete, it is real, for me, for Juani, for Joan, for Albert, for Maria. The dimension of this pain, of these losses, is unimaginable. I have tried to calculate the number of streets, the blocks, the houses in each street, in each block, in each affected city. I lose count almost always at the beginning. Somewhere I have read that the number of people affected by the DANA is more than two and a half million people. We don’t know yet, because there is no coverage and we can’t look at the networks, that the number of bodies recovered has been increasing during the day. There will be almost 200 by the end of the day. The obsession with data, with numbers, feeds new fears and new panics. Always after the event, the data come to put fear in our bodies, to scare us, to immobilize us. COVID-19 has been a school of learning statistics for everyone. A few days later, today, when I have not been able to go to help because in the Valencia that has been saved we are working, I will ask those who have been able to go for Juani.

It is getting late and we think of leaving before nightfall, before there is a traffic jam. Thank God we are pulled out of these extemporaneous and bizarre, bourgeois considerations by the soldiers who have just arrived on the fourth day, at last. They are received with joy, but also with indignation. They will prefer not to say anything, they follow orders. A friend whose son is in the army says they have been ready since Wednesday. Here there will be another reason for controversy, there already is, because one and the other will accuse each other of having prevented the sending of troops. There is an army of useless and inexperienced volunteers when the first soldiers arrive. They approach and ask for our help to move the remains of the collapsed wall of a school away from the road. It’s 5:30 pm, and our conversations are full of criticism of the politicians, the perfect scapegoats for everything that has happened, because they are objectively guilty, we say. We don’t know yet that in a couple of days they will be about to be lynched.

It takes us two hours to drive home. The queue is enormous: people in cars returning; people walking and carrying water bottles and bags of food, shovels and brooms, cleaning products, diapers; a human river of seven kilometers, those that separate us from the capital.

Day 5. Saturday, November 2, All Souls’ Day

I wake up late and I don’t know if I will go; my friends have already left. They call me to go to pick up material from a chemical company in the north of Valencia, in Honda, and we go to get PPE, shovels, brooms, and water boots. We also take a hydraulic pump. There we meet other workers who have gone to get material to go to other places. They all have stories to tell: the daughter of one of them, a high-performance athlete, has been locked up for two days in the sports center where she lived, unable to contact anyone. She is a teenager. Another tells me that his friend has lost everything; he has a bar and the flood has taken everything inside. All the stories are similar in one thing at the moment: no one is afraid to go to help, no one is really looking for culprits—because they are there, at hand, in the news. Responding to the call of another and not thinking about one’s own safety. This simple act of holiness. Soon enough it will be said that they were foolish, reckless, that they disobeyed. Many will do so out of mimetic inertia, but even that mimetic gesture reflects the first heroic act of the one who went without asking to give aid before the institutions. Along the way we talk about logistics, about what should have been done, about possibilities. Everyone is right and everyone is wrong. We arrived at dusk, dressed in PPE, boots, gloves and mask. And we set about pumping water out of a basement. The firemen have left us a very powerful one until morning, we have to take advantage of it. It’s getting dark fast. The light has returned to some houses – those that have received the visit of fellow electricians who have checked the installation and have made repairs – but not to the street lamps. In the square a police car stands guard to prevent theft and looting, and other cars patrol the streets. On the third day a friend from another town had told me that no one had been there and that they were hiding at home because they were afraid to go out. Others tell me similar stories. We all know many people who are in danger and in need, how do we choose? Who do we help first? These kinds of dilemmas are the ones I pose to my students in ethics class, the mental experiments. They are of no use, in the here and now. It is night and the landscape looks more like a stage than ever and I take a picture: a powerful spotlight illuminates the cars that have been pulled off the streets to gain access to the houses. An anchorwoman is ready to go live on the evening news. It’s early for Spanish time, but it seems much later. Someone at home will be watching this same thing I’m watching now, without seeing what I’m seeing.

The pumps get stuck and we spend all night unclogging them and moving them around, carefully because the roof is falling down. The policemen come to greet us. They are from another city, another place, they have just arrived. They don’t believe what they see, the situation, nothing. They don’t see what their eyes see or they don’t want to believe it or see it, but they see it and open their eyes wide. They are afraid, they are in a neighborhood they don’t know, in a city they don’t know, in a situation they have never faced. But they stay at their post all night until the shift arrives.

I write to Curtis, asking him if I can send him a text for the Bulletin. There is another apocalypse, besides the catastrophe, besides charity: it is that of the witness, that of the one who testifies to what he has seen, what he sees and what he will see. I have just written to an Italian professor, who asked me if we were well, that this is terrible, but that in the midst of the horror—and there is always a greater horror that not everyone is allowed to see—shines the gesture of the one who stays and remains at the side of the victims in spite of everything.

Day 6. Sunday, November 3

In the morning comes the new shift of volunteers. There is almost no water left in the basement, but two of the four pumps have broken. What is left will have to be taken out by hand, bucket by bucket. They take the broom, like St. Martin de Porres, the saint of the day, and start cleaning the mud they already cleaned yesterday. They do it with joy. We rouse ourselves and leave. I take a picture just before I leave of something that was hidden under the water in one of the rooms we have cleaned. It is the third picture I take.

I get home, shower and disinfect and, like the previous days, we put the clothes in the wash to remove the mud. The washing machine is going to jam. Seeing the sunrise has been impressive. With the day came floods of volunteers who do not get tired. Back home, I think: “I have a dry and clean house and a family waiting for me, all safe and secure.” A certain shame, a feeling of guilt that won’t go away, lurks and waits for us to let our guard down to paralyze us.

I sleep until I don’t know what time, and when I wake up the President of the Government, the President of the Generalitat and the King of Spain are visiting Paiporta. I wake up as if a mimetic angel had whispered to me “wake up and look”. They are about to lynch them. The President of the Government, Pedro Sanchez, is leaving in an official car. They have thrown reeds and mud at them, sticks that are reeds, that fill everything, carried by the flood from the ravines. Reeds that we have used to remove the mud and unblock the drains —Reeds and mud is the title of a novel by the Valencian naturalist writer Blasco Ibáñez, they are important symbols of Valencia. The King stays and approaches to talk to those who insult him. Then will come the interpretations: that they should not have visited Paiporta, that the President recommended him not to make the visit, that it was a way to provoke, that there is no dialogue with the violent, that they were ultras groups that want to discredit the government. It is incredible how the information machines take an image and distort it, how they make images speak to say such different things. I see a man who has been called a murderer, who has had mud and sticks thrown at him, running away. I see another man who has been called a murderer, who has had mud and sticks thrown at him, who has stayed to talk. I see his wife, Queen Letizia, crying as she wipes the mud off her face. I wonder if they are thinking about the images they are generating when they talk to those who rebuke them, when they embrace, when they are rejected, when they take the hands of those who rebuke them. The image machine is going to gobble up hundreds of photos and videos. I don’t think I care what they say. Those of us who have read Girard know what happens to kings in crises. Rulers are lynched. The lynch mob was activated in Paiporta in a few seconds. The gesture of one of them was enough. To deactivate it, it was enough the gesture of another one, who stayed to speak. It doesn’t matter what he said, nor with whom he spoke. We have all been moved by something in this image. Later we will make the image say other things, but sometimes, just sometimes, an image makes us say or feel or think the right thing. It moves us, it invites us to follow a new inertia that breaks with other inertias that are as old as man, that of reproach and revenge, that which generates the community of the guilty. A certain hope is born in us. Although we resist, we do not want to abandon ourselves to it, it is crazy. Small circles form around the one who has remained, and he addresses each other, creating, I would like to think, communities of the hopeful. The mud of the media will reduce everything to the usual war between good guys and bad guys, but I only see people talking, disagreeing, looking at each other and listening to each other and hugging and crying together. They are images that remind me of other images, emblems of reconciliation and forgiveness, icons of love and charity.

In the flood there has been a revelation. The Apocalypse of John reveals the Lamb, who is Love. The caritas, the agape, has been revealed in the small: in the muddy boots; in the walks along the destroyed roads carrying mops, buckets, jugs of water and food; in every embrace and in all the shared tears. Death has pronounced itself tyrannically, with an unbearable roar, but it has received a hidden, silent response from people who walk and come to the margins of the city. The last word is not theirs, although it seems so in these hours of weeping, mourning, and desolation. It belongs to Love. And the waters cannot drown it.

In the hall of Juani’s house there is an umbrella stand with many umbrellas and a bottle of bleach, all covered by mud. I couldn’t help taking that image with my smartphone, it was the first picture I took. There is something in those objects that catches me: it is the protection, the everyday of cleaning, of going out when it rains and your grandmother telling you to take the umbrella, of cleaning every morning the floor of your house, so that it is clean and ready to welcome visitors. The mud covers everything and renders them useless. The hospitality has become impossible, the hospites arrives and receives those who receive and does not end up reaching this present that cannot be assumed. The house has become uninhabitable. But only man is capable of inhabiting the inhospitable, of making the desolation welcoming. Juani will receive us tomorrow, Monday, and she will cry because no one has been to see her for two days. Her daughter is with her. We go in to help her get rid of everything, her kitchen, her rooms, her memories. The umbrellas are still there, with the bleach; or not, they have already been cleaned and the bleach has been used. Twenty young people have come in to help her. She cries inconsolably—who knows if so much pain and so much love is bearable. In spite of everything, her image at the door of the house, saying goodbye gratefully, full of mud, will stay with me for a long time.

I finish these reflections on Tuesday, November 5. Yesterday I could not go. Life goes on, my students need to be consoled as well, many have been affected and we have to see how to continue with classes. I have to resist the temptation to feel guilty or ashamed. In the program I run, with students from the USA, we have to make decisions quickly: how the teachers are doing, how we will continue with the classes, what actions we can take. Soon it will be Thanksgiving. We would like to go and celebrate it there, and have the students be the waiters at a banquet in the midst of chaos, like the end of a Kusturica movie. It’s a sentimental and perhaps a bit sappy image. The future is uncertain. As Esquirol says at the beginning of La resistencia íntima and in La penúltima bondad, in the face of the desolation and nihilism of the images we have seen and which have engulfed us, we have the hope of being able to share, on the margins of the city, bread and soup, with those who have nothing, and that this soup tastes good.

I finish these reflections on Tuesday, November 5. Yesterday I could not go. Life goes on, my students need to be consoled as well, many have been affected and we have to see how to continue with classes. I have to resist the temptation to feel guilty or ashamed. In the program I run, with students from the USA, we have to make decisions quickly: how the teachers are doing, how we will continue with the classes, what actions we can take. Soon it will be Thanksgiving. We would like to go and celebrate it there, and have the students be the waiters at a banquet in the midst of chaos, like the end of a Kusturica movie. It’s a sentimental and perhaps a bit sappy image. The future is uncertain. As Esquirol says at the beginning of La resistencia íntima and in La penúltima bondad, in the face of the desolation and nihilism of the images we have seen and which have engulfed us, we have the hope of being able to share, on the margins of the city, bread and soup, with those who have nothing, and that this soup tastes good.

I have used the first person plural to include all those who were with me. This is an account, or rather, a relación of the disaster. I don’t pretend to explain what happened, but to narrate what we lived through before forgetting it. There are disguised quotations from people who have told me their stories, from books I was reading or that came to my discourse summoned (Esquirol, Villoro, Levinas, Benjamin, Mayorga, Paul of Tarsus, John of Patmos, Sontag). Images say a lot, but they must be made to say, because they reveal and veil at the same time. Seeing without seeing and hearing without hearing is the most frequent thing. It is essential to stop and look carefully and listen calmly. To look at the apocalypse face to face and see, at last, the other who suffers beside me and has asked me for help.

Carte desde… Valencia

Cuando llega el apocalipsis y solo puedes mirar

Reflexiones sobre las imágenes de una tragedia

David Garcia-Ramos Gallego

Cuando uno vive de cerca una catástrofe le aborda una sensación de ensueño e irrealidad, un desasosiego que es difícil de explicar: el horror, la angustia, el desconcierto, la confusión, la rabia. Es como si al llegar el fin del mundo—al menos el fin del mundo de uno, de ese conjunto de seguridades sobre el que nos movemos cada día—como si al llegar el apocalipsis, solo las imágenes de la destrucción y del mal fueran verdaderas. El desconsuelo y la desesperación hacen que, abandonada ya toda esperanza, nos adentremos en el infierno.

El sábado por la noche pensé en los miembros del COV&R y en este Bulletin y decidí escribir a Curtis para proponerle unas líneas sobre lo que estaba sucediendo. Era la madrugada del sábado al domingo, las 2 am, en Catarroja, una de las zonas afectadas. El silencio era sepulcral y se veían muchas estrellas—algo raro en el área metropolitana—y las montañas de barro y de coches apilados eran como un escenario de película de guerra. Desde el principio tuve presente el pensamiento sobre la catástrofe de Dupuy, y al último y controvertido Girard apocalíptico, y me pareció que podría juntar algunas palabras que pudieran iluminar este paisaje desde la teoría mimética. No era consciente hasta qué punto iba a ser posible hacerlo ese mismo domingo.

Las imágenes, nos recuerda el escritor mexicano Juan Villoro en un reciente ensayo, no valen más que mil palabras. Las imágenes no dicen nada. Las imágenes dicen lo que nos dicen a nosotros. Hay que interpretarlas, ponerlas en contexto, comprender la intención del autor o del que la utiliza sin permiso del autor; las imágenes tienen así varias vidas. Muchos amigos de todo el mundo, de Madrid a Aalst, de Mexico a Catania, de New York a Hradec Kralove, de Guam a Santiago de Chile, de Puerto Rico a Padova, me han escrito estos días preocupados, asustados por las imágenes. Lo que sigue es el comienzo de un intento de pensar, narrativamente, la catástrofe y el apocalipsis, desde dentro y sin las limitaciones de un discurso académico. Decepcionará a casi todos, empezando por mí, pero es necesario contar las imágenes para que las imágenes cuenten. De modo que os pido disculpas porque habrá solo tres imágenes.

Porque lo que hay que ver es “lo que ni el ojo vio, ni el oído oyó, ni al corazón del hombre llegó”. Lo que hay que ver es el apocalipsis.

Día 1. Martes, 29 de octubre

El martes por la tarde comenzaron a llegar las primeras alertas meteorológicas por parte de los distintas servicios y responsables civiles en Valencia. En Xàtiva y Alzira se suspenden las clases, algo que es habitual, porque todos los años se produce el fenómeno que hoy llamamos DANA, pero aquí se ha llamado siempre “Gota Fría,” y que todos los años provoca incidentes de distinta gravedad. Nadie podía imaginar qué iba a suceder. Todos actuamos por inercia—inercia mimética. Como yo soy de Madrid, todo los años bromeo sobre lo nerviosos que se ponen los valencianos por “cuatro gotas”. Me iba a arrepentir de esas palabras. Otros se encierran presa del pánico y los más prácticos sacan el coche del garaje para que, si entra el agua—lo hace en ocasiones, 20 o 40 centímetros a lo sumo—no se manchen. Los aparcan fuera, en las partes altas de la ciudad, en puentes, etc. Es la hora del regreso a casa, tras el trabajo, las clases en la universidad o las compras en los centros comerciales. Durante todo el día anterior y este día ha llovido con intensidad en Valencia y alrededores, pero ahora mismo no llueve. Seguimos nuestras actividades con normalidad. Sobre las 17:21 horas comienzan los primeros problemas en el metro y un antiguo alumno, que estaba asistiendo a un congreso de Filosofía y cine en nuestra universidad, y al que hacía tiempo que no veía, decide volver a su casa antes de que termine la última conferencia. Quiere acercar a otro compañero a su casa en coche, porque han leído en las redes que el metro no funciona. En un coche nuevo que perderá para siempre en unas horas para poder salvar la vida. Llegamos a casa y empezamos a oír las noticias, pero no somos capaces aún, ni viendo imágenes, de imaginarnos lo peor que ya estaba sucediendo.

Día 2. Miércoles, 30 de octubre

Las clases no se van a suspender hasta las 15 horas. Hemos necesitado casi 24 horas para asimilar lo que nos cuentan. Lo que nos cuentan los testigos a través de las imágenes que nos mandan. En una sociedad del instante y de la imagen es increíble lo que hemos tardado en responder. En Valencia centro, a solo 10 minutos en coche del desastre, no ha sucedido nada. Y actuamos como si no hubiera sucedido nada, miméticamente. Seguimos con el congreso a pesar de todo. Aunque ya han empezado a suceder cosas, las sabemos por los que sobreviven, de modo que aún no hay víctimas, solo supervivientes.

Esta mañana bien pronto un compañero ha ido a buscar en moto a nuestro antiguo estudiante. Estaba en un pabellón deportivo a donde le han conducido las fuerzas de seguridad a las 7 am. Casi no ha dormido y se ha puesto unos calcetines secos que le han dado, pero sigue vestido con la misma ropa y las mismas deportivas, que tienen barro. Las miramos cuando nos las enseña. Vemos sin ver. Y oímos sin oír lo que nos cuenta. Reflexionamos sobre los dilemas—salvar el coche o salvar la vida—. Nos cuenta que una mujer se ha quedado en el coche. Él mismo ha dudado: solo hace 3 semanas que lo compró. Camina hacia un puente para huir de la corriente de agua y allí un conductor de autobús de línea hace bajar a todos los pasajeros para irse a casa él mismo y dejarlos allí. Mientras vamos procesando todo esto, hablamos de Wim Wenders, de Aki Kaurismaki, de John Ford, de Jean Renoir, de Yasujirō Ozu o de Terrence Malick, y de los filósofos Stanley Cavell, Gabriel Marcel o Josep Maria Esquirol. En nuestras preguntas e intervenciones se va colando, lentamente (¡demasiado lentamente!) el Evento. Después de comer un compañero me dice que ha fallecido la abuela de otra compañera. El relato es de película de terror: estaba enferma y en cama, las cuidadoras han elevado la cama todo lo que han podido y se han ido a buscar una ayuda que llegaría demasiado tarde. El horror, la catástrofe, el apocalipsis, se va revelando en su primera forma, la del mal, y lo hace en imágenes que no hemos visto aún—o que hemos visto poco, como apartando la mirada—: las imágenes de la imaginación, las imágenes que han pintado en nuestra mente las palabras de los supervivientes, de los testigos. Al acabar el congreso, sin saber qué hacer, vamos a cenar. Será una sopa que después tendrá un regusto amargo—no como la sopa de la que hablan Levinas o Esquirol, la que compartimos en la mesa con nuestros amigos; sino como la del campo de prisioneros de Elie Wiesel, un sopa amarga que otros, las víctimas y supervivientes, no van a poder tomar ni degustar—. Hablamos de proyectos de futuro, de la esperanza de los sin esperanza, de la sociedad de los desposeídos y de los “al margen” de las películas de Alice Rohrwacher. Sin saberlo, el proyecto toma forma a menos de 10 minutos en coche, una forma desoladora, macabra, mortal.

Día 3. Jueves 31 de octubre

Se anulan las clases en la universidad todo el día. Los primeros voluntarios comienzan a llegar y con ellos llegan los relatos. Es cierto que recibimos imágenes terribles en nuestros móviles, pero es como si la saturación de las imágenes y la adioforización del mal—de la que habla Bauman—nos hubieran anestesiado. Se parecen demasiado a otro males morales, los de la guerra en Gaza o las ciudades devastadas de Ucrania. Como si hubiera un eco entre ambas imágenes, algo que secretamente las conectara. Este día las imágenes se han multiplicado, pero también los relatos. A pesar de que vivimos en una cultura de la imagen, necesitamos que esas imágenes tengan significado—o un significado más que el turístico con el que parece que contemplamos las fotos de atrocidades o de víctimas, como señaló Susan Sontag—. Necesitamos que alguien nos diga que esa imagen es cierta, que nos la sitúe en una red de significaciones, en una constelación de sentido, una suerte de iluminación profana, en palabras de Benjamin.

Es en este momento en el que empiezan a producirse las primeras interpretaciones de esas imágenes, que empiezan a utilizar en la arena política los máximos responsables de la gestión de la catástrofe: los coches abandonados, apilados unos sobre otros por la fuerza del aluvión, las calles llenas de lodo y de objetos arrastrados. Todo empieza a formar parte del escenario que los medios van a montar para que llegue a todas partes. Como siempre, la realidad va a superar a la ficción, no solo porque el olor será una bofetada que nos despierte a todos de la contemplación alucinada de las imágenes, sino porque esas imágenes no las podremos separar nunca de las personas que nos las cuenten: Juani, Ana, José, Pepe, Lucía, Joan….