No. 50 December 2016

Contents

President’s Report – Report on COV&R’s Activities at the 2016 American Academy of Religion

Musings from the Executive Secretary – Report on “Intersubjectivity, Desire, and the Mimetic Brain: René Girard and Psychoanalysis”

Conference 2017 – Identity and Rivalry, July 12-15, 2017, Madrid, Spain

Membership Services Update

Editor’s Column – The Editor’s Journey

Book Reviews

News

President’s Report

COV&R Activities at the 2016 American Academy of Religion

by Jeremiah Alberg

The year that has passed since the death of René Girard has given different scholarly organizations time to arrange suitable tributes in his honor. This was certainly true for this year’s AAR meeting, held November 18-22 in San Antonio, Texas. COV&R co-sponsored a session with the Theology and Religious Reflections Section and the Sacred Texts, Theory, and Theological Construction Group on the theme, “René Girard: Religion and the Legacy of Mimetic Theory.” There was another session titled: “Further Reflections on René Girard, Religion and the Legacy of Mimetic Theory.” In addition, COV&R had own Book Session, first on the newly published translation, René Girard and Raymund Schwager: Correspondence 1974-1991 (translated by Chris Fleming and Sheelah Treflé Hidden and edited by Scott Cowdell, Chris Fleming, Joel Hodge, and Mathias Moosbrugger), and second on Sandor Goodhart’s recent book, The Prophetic Law: Essays in Judaism, Girardianism, Literary Studies and the Ethical. Meanwhile, William Johnsen cheerfully manned the book booth for Michigan State University Press’s “Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture Series.” Keith Ross, Suzanne Ross, and Adam Ericksen, representing the Raven Foundation, were active in gathering interviews for their website. Suzanne was also spotted passing out spiffy cards that explained both what the Colloquium on Violence & Religion is (International, Interreligious, Innovative) and the benefits of becoming a paying member.

Finally there was very pleasant Book Launch and Wine Reception for the above mentioned Correspondence volume, sponsored by the publisher Bloomsbury and T&T Clark. Sandor Goodhart shared some reminisces from around the time that Girard and Schwager began to get to know each other.

The events took place in what has to be described, at least from the perspective of the vast majority of the people present, as the “shadow” of the election results. There were not a lot of vocal Trump supports carrying an AAR tote bag. But that led to many interesting conversations about how to understand the present political situation from a mimetic viewpoint. How does one respond to the election of Donald Trump in a way that does not contribute to the further coarsening of our political discourse was one recurrent theme in our conversations.

The panel on the Correspondence began with the reflections of the two translators, Chris Fleming and Sheelah Treflé Hidden, on the task of translation. Joel Hodge spoke on the some of the key themes that emerged from the letters, and Scott Cowdell spoke about “Girard among the Theologians.” Correspondence is a genre whose very existence is threatened with recent developments in communication. The Girard and Schwager correspondence ends as COV&R is founded and they are able to meet face-to-face on a more regular basis. Naturally, the two were not writing for publication, and both were struggling to formulate thoughts that were new to themselves, so there are ambiguity and difficulties. There is also a kind of freshness and the joy of discovery. As Hodge pointed out, the letters are a valuable resource not only for tracing Schwager’s influence and Girard’s development on the important topic of sacrifice but also for looking at such topics as their understanding of Paul and of the Law. Cowdell provided an important quotation from the correspondence in which Schwager gives expression to his interpretation of Girard’s position on the Fall and why the evidence for the prelapsarian condition is historically unavailable. The innocent or unfallen state never existed historically, although it was an existential possibility. Humans chose violence. I think that the Correspondence will provide resources for a deepened understanding of both Girard’s theory and Schwager’s theology.

COV&R Object: “To explore, criticize, and develop the mimetic model of the relationship between violence and religion in the genesis and maintenance of culture. The Colloquium will be concerned with questions of both research and application. Scholars from various fields and diverse theoretical orientations will be encouraged to participate both in the conferences and the publications sponsored by the Colloquium, but the focus of activity will be the relevance of the mimetic model for the study of religion.

Musings from the Executive Secretary

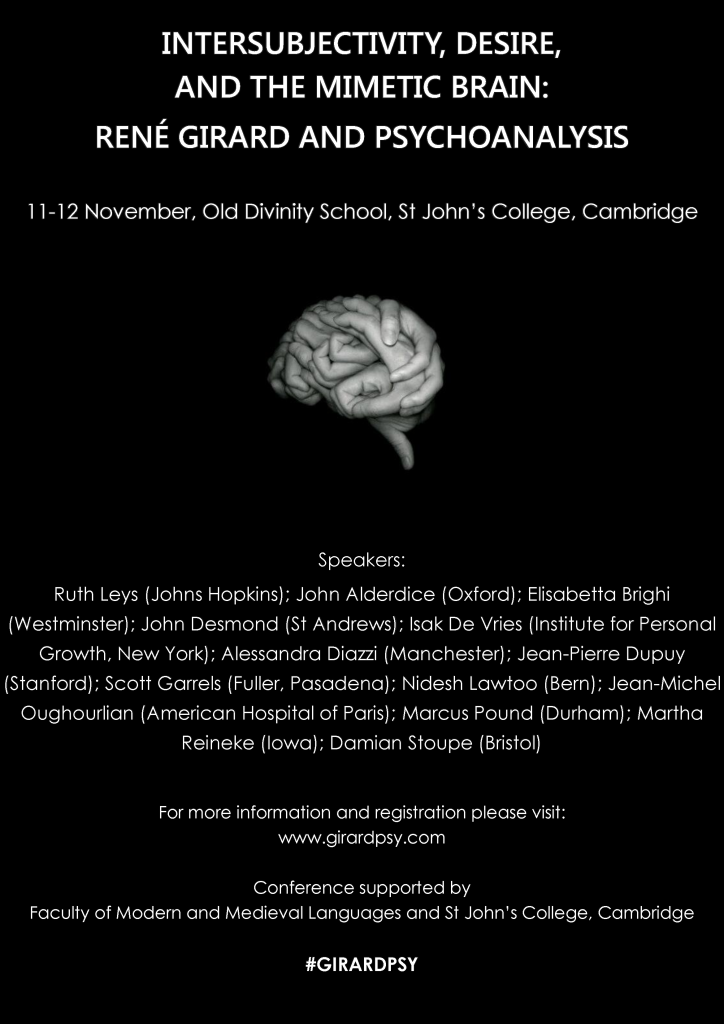

Report on “Intersubjectivity, Desire, and

the Mimetic Brain: René Girard and Psychoanalysis”

by Martha Reineke

University of Northern Iowa

A conference on mimetic theory and psychoanalysis was held November 11-12, 2016 at the Old Divinity School, St. John’s College, Cambridge. Planned and hosted by Pierpaolo Antonello, with the support of Alessandra Diazzi and Scott Garrels, the conference provided a welcome opportunity for scholars and clinicians (psychotherapists, psychoanalysts, and psychiatrists) to explore a long-neglected topic: the relationship between Girard and Freud, mimetic theory and psychoanalysis. Girard modeled such dialogue when he asserted in Mimesis and Theory that “literature and psychoanalysis in the best sense need each other” and wrote in Evolution and Conversion that Freud’s texts “support and validate mimetic theory.”

Keynote speaker for the conference was historian Ruth Leys, professor emerita from Johns Hopkins University, whose research focuses on the history of psychology and psychiatry. She is the author of Trauma: A Genealogy, From Guilt to Shame: Auschwitz and After, and the forthcoming The Ascent of Affect: From the 1960s to the Millennium. Leys focused on recent history of empirical research in psychology and neuroscience with the aim to report on features of Girard’s claims about mimesis that have been confirmed empirically. Her conclusion? “Girard got a number of things right” in terms of processes of cognition and the social context of mimesis. Most significant, Girard’s focus on the social function of mimesis both anticipates and supports recent empirical research that has challenged earlier research on human imitation. That research posited largely autonomous functioning of mimicry in humans and primates; more recent research shows that imitation is oriented toward communication. Of particular note, Leys concluded, is Girard’s distinctive focus among scholars of imitation on conflictual mimesis.

Topics explored by other presenters demonstrated the utility of bringing Girard and psychoanalysis together in conversation. Nidesh Lawtoo (Bern) and Jean-Pierre Dupuy (Stanford) brought Girard’s anthropology to bear on psychoanalysis. Lawtoo spoke on “Violence and the Mimetic Unconscious,” in which he discussed discontinuities between Girard’s anthropology and Freud’s early theory of the unconscious. Dupuy offered a paper on “Lacan’s Twelfth Camel,” an engaging reflection on how Lacan and poststructuralist thinkers of his time missed the structure of self-transcendence that lies at the heart of Girard’s theory. Marcus Pound (Durham) continued in the Lacanian mode with a presentation on “Lacan, Mimesis, and Comedy” in which he suggested that Girard’s focus on the tragic blinds him to positive forms of mimesis in Lacan, particularly in Lacan’s examination of humor. Martha Reineke (University of Northern Iowa) presented on a neglected aspect of Girard’s theory: embodied trauma. Drawing on Françoise Davoine’s book, Fighting Melancholia: Don Quixote’s Teaching, which argues that Cervantes’s novel attests to intergenerational war trauma, albeit with a fictional son, Reineke suggested how mimetic theory can be enhanced by greater attention to trauma.

Elisabetta Brighi (Westminster), Lord John Alderice, and Alessandra Diazzi (Manchester) linked mimetic theory and psychoanalysis with the topic of political conflict. Brighi explored global resentment, distinguishing between two forms of resentment that point to two emotions. One form, rightly recognized by Girard as toxic, merits continued critical reflection drawn from Girard’s insights on acquisitive rivalry. The other form, motivated by emotions founded on a sense of injustice, needs to be explored further in order to determine how its mimetic attributes align it with what some Girardians call positive mimesis, rather than with acquisitive rivalry. Alderice, Director of the Centre for the Resolution of Intractable Conflict and a psychoanalytic psychiatrist, played a key role in brokering the Northern Ireland peace accord in 1998. He spoke on links between Girard’s theory and the psychopathology of large groups, describing the particular salience of mimetic theory for illuminating features of intractable conflicts. In addition, he highlighted the risks of religious illiteracy in a time when some conflicts have the potential to become global catastrophes. Diazzi compared Girard with Italian psychoanalyst Elvio Fachinelli through examination of Fachinelli’s attention to anti-authoritarian pedagogy, group analysis, and the student protests of 1968. She showed how his analysis of these topics was shaped by a psychoanalysis of intersubjectivity with striking resemblance to mimetic theory.

The social context of a conversation between mimetic theory and psychoanalysis was the focus of two additional presentations. John Desmond (St. Andrews) explored advertising, offering a Girardian analysis of the self-absorption of models. Damian Stoupe (Bristol) addressed workplace bullying, drawing on Girard to argue that bullying is a variable in workplace “mobbing,” which enables an organization to identify and expel an employee scapegoat.

A conference highlight was a much appreciated conversation with Jean-Michel Oughourlian, author most recently of The Mimetic Brain. In what amounted to a superb master class in psychoanalysis, Oughourlian shared with conference attendees the major themes of the book, walked everyone through chapter highlights, and offered compelling examples from his clinical practice. As would be the case with an actual master class, Oughourlian took numerous questions from conference attendees, answering each one with care and unflagging bonhomie.

Rounding out the conference were presentations from perspectives that joined the clinical and theoretical by Scott Garrels, a psychotherapist from Pasadena, CA, and longtime Girardian, and Isak De Vries, Institute for Personal Growth, NY. Garrels’s presentation focused on trends in contemporary psychoanalysis and psychotherapy over the past several decades, showing how clinicians have moved closer to espousing relational perspectives with strong similarities to mimetic theory. Garrels analyzed how mimetic theory and psychoanalysis can build on this enhanced proximity to address respective weaknesses: mimetic theory lacks a model of the human mind which, if developed, could enhance its capacity to describe conversion from acquisitive rivalries. And psychoanalysis would benefit from a robust account of the role of imitation in intersubjective relations. DeVries shared reflections on working clinically with a transgender population and applied the work of Lacan, Girard, and Winnicott to an analysis focused on clarifying the role of images in identity construction and how these images can release violent passions focused on annihilating differences in ourselves and others.

Much appreciation is due to Antonello and the organizing committee for this first conference on mimetic theory and psychoanalysis. All agreed it was a productive exercise which merits imitation.

COV&R 2017 Annual Meeting: Identity and Rivalry

July 12-15, Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, Madrid, Spain

The process to build identity follows different ways/paths: narrative, ritualistic, mythological, political, etc. Nationalisms, indigenisms, religious revivals, political and economic protests, crowd-based movements, the dynamics of identity have become more and more complex. Spain has been a country of cultures, rivalries, conflicts and fratricidal wars, but has been too homeland for great artists: Cervantes, Velázquez, Calderón de la Barca, Goya, García Lorca, Picasso… Their contributions to the understanding of human nature has been revolutionary. Girard’s predilection for Cervantes is well known.

We want to invite participants to explore the roots of identity, the ways rivalry takes to survive and to rise across the centuries as a force of destruction and foundation. Nowadays, Spain constitutes a privileged window to explore the possibilities and limits and the actual identity of our world.

The program is still in early stages of development. Below are preliminary lists of topics.

Concurrent Sessions

- Nationalisms: the inter-nation rivalry

- Spanish Civil War: memory and identity

- Indignados and other protester movements

- The construction of European identity: politics, culture and religion

- American identity from colonialism and empire to independence and revolution

- Identity, Religion and Communion: from Middle Age to Contemporary Age

- The European Identity after the BREXIT and the Refugees Crisis

- Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Spain and the Possibility of Peace

- Identity and the Mimetic Brain

- South American Identity

- Schwager Prize

- Nation, State and Identity

For more information, visit the conference website.

Membership Services Update

By Executive Secretary Martha Reineke

At the COV&R Board and Business meetings in Melbourne, we voted to contract with the Philosophy Documentation Center for membership services. Expressing strong appreciation to our treasurers for their oversight of the budget as well as membership services, the Board freed our treasurers from their responsibility for membership services as part of a larger upgrade in online communication with our membership on the COV&R website.

For over fifty years, PDC has offered professional services to the academy, including the publication of reference materials, books, and journals. It also hosts membership services for a number of professional organizations, including COV&R. With our move to PDC, we no longer have separate American and European membership services. All services are now provided by PDC. When you visit our website now to become a member or to renew, you will be redirected to a membership page on the PDC site.

In one of its first actions in support of our membership, PDC sent renewal notices to our lapsed members: emails were sent to our American membership list and letters through the postal service were sent to our European membership list. In the past month, fifty lapsed members have rejoined COV&R. If you are reading this and are not yet a member, we invite you to join COV&R now. If you are a lapsed member or a member who needs to renew but have not received a renewal invitation from PDC, please click on the membership link on the website and complete the membership process.

From now on, PDC will be sending automatic renewal notices to all members, which should reduce the number of lapsed memberships. In addition, PDC will be managing and regularly updating the mailing list for books from Michigan State University Press.

Still in the process of coming on board are several additional PDC services. The Bulletin will become again, as it was in the past, a members-only benefit. Given the Bulletin’s value to our membership, this benefit should contribute to making our membership numbers even more robust. Contagion also will become electronically accessible to members at the time of publication, making possible immediate electronic access and the downloading of articles to member computers and laptops. In addition, COV&R members will be able to subscribe to the Journal of Violence and Religion at a reduced cost.

Total PDC services cost 50 cents more per member than did our previous credit card processing service. And that service only covered the processing of credit cards. There were no additional benefits. We anticipate more than covering our increased membership expense with membership growth. At the board meeting next July, we will revisit our contract with PDC and update it as needed. In the meantime, if you have any difficulties accessing PDC services, please contact them. They have been highly responsive so far. General questions about COV&R’s relationship with PDC may be directed to me.

All of these changes are exciting and hold potential not only for enlarging our membership but also for funding enhancements in scholarly resources available to our members. As we secure our presence in the 21st century with a larger online footprint, the community of Girardian scholars and practitioners of mimetic theory grows even stronger.

Editor’s Column: The Editor’s Journey

by Curtis Gruenler

While many COV&R members attended the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion (see Jeremiah Alberg’s report in this issue), I took a road trip from Holland, Michigan, to Iowa City, Iowa, for a “summit” of leaders from congregations that belong to a new network called Blue Ocean Faith. I had met several of these folks, including the pastors of host Sanctuary Church, when they participated in last summer’s Mimetic Theory Summer School. Blue Ocean Faith is pursuing, more adventurously than anyone else I know, what it might mean to include mimetic theory as a guiding ingredient in forming a local relational community.

While many COV&R members attended the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion (see Jeremiah Alberg’s report in this issue), I took a road trip from Holland, Michigan, to Iowa City, Iowa, for a “summit” of leaders from congregations that belong to a new network called Blue Ocean Faith. I had met several of these folks, including the pastors of host Sanctuary Church, when they participated in last summer’s Mimetic Theory Summer School. Blue Ocean Faith is pursuing, more adventurously than anyone else I know, what it might mean to include mimetic theory as a guiding ingredient in forming a local relational community.

They are still using the word church for these communities, but they are conceived in unchurchy ways—much like Mimetic Theory sees Christianity as an anti-religious religion, a movement formed out of the undoing of sacred violence rather than its perpetuation. The name “Blue Ocean” comes from marketing strategy: the red ocean is where competition is already intense, but it also attracts more competitors; the blue ocean is relatively free of competition. Blue Ocean churches share a calling to highly secular, unchurched places, like Ann Arbor (Michigan), Cambridge (Massachusetts), and Santa Monica (California). At the same time, the image of the red ocean fits a Girardian understanding of the rivalries that usually drive communities. The blue ocean could label the challenge of harnessing mimesis in a different way, for a more peaceful community.

Among the six “distinctives” of Blue Ocean Faith, articulated in a series of essays by Dave Schmelzer on the Blue Ocean blog, is the core metaphor of centered-set. The usual way of defining a group of points on a plane is a bounded set that draws a ring around some points that leaves the rest outside. A centered-set instead imagines the points in motion, identifies a center, and asks whether any point, no matter how far from the center, is moving toward it or away. There is no boundary. Membership is less marked, more active and intentional, always available by a mere change of direction, and, above all, not based on exclusion. Again, though this metaphor does not come from Mimetic Theory, the compatibility is obvious.

At the summit, one of the pastors of the Blue Ocean church in Ann Arbor, Emily Swan, gave a lucid, inspiring, well-received introduction to Girard’s work and its implications for theology. She testified to her own experience of wrestling with a version of Christianity that made God into a rival and finding, through Girard, a better, more inviting understanding of the Christian story, one that opens a way to unity in the Spirit that “holds diversity without differential status” and aids Blue Ocean’s mission of “making an experience of the goodness of God accessible to everyone.” I highly recommend the audio recording.

Swan’s emphasis on story fit with another element of the summit, a talk by Schmelzer on how myths of the hero’s journey might offer a fresh take on Christianity (also the subject of a series of podcasts, the first one available here). He drew on the work of Joseph Campbell, aware that Campbell is among those Girard rightly critiques for reducing Christianity to just another myth. Nonetheless Schmelzer succeeds in bringing out how the idea of crossing from the “ordinary world” into the “special world”—with its attendant motifs like supernatural aid, mentors and helpers, transformation and atonement—offers rich ways of recognizing what it is like to be moving toward Jesus as the center and, indeed, how the center has always and everywhere been accessible to and moving toward us. The ordinary world is a life of reactivity that Campbell describes in ways easily translatable into mimetic rivalry. Attempting to cross the threshold out of the ordinary world, we meet guardians who claim to stop us for our own good but whose imaginations are, like ours, stuck in a world of scarcity, envy, and fear. The special world, by contrast, is one of abundance and bliss. Crossing the threshold is a way of thinking about what it means to lose one’s life for the sake of Jesus and the Gospel (Mark 8:35).

I listened, on the way to Iowa, to the famous series of conversations between Campbell and the TV journalist Bill Moyers called “The Power of Myth.” It struck me that Campbell is quite good at selecting and retelling stories that convey a summons to communion with a transcendent presence. He contrasts this with the violence of what he calls “the system,” though with little attention to how it works or, especially, to the kinds of stories that support it—the stories that Girard focuses on when he talks about myth. Girard and Campbell emphasize opposite aspects of myth, whether because they are looking at different sides of the same thing or at different collections of stories. Campbell looks for what Girard (or J. R. R. Tolkien or C. S. Lewis) might see as glimmers of the Gospel. Campbell gives no attention, at least here, to the function of any kind of myth in history; instead he romanticizes the heroic quest of the individual to escape “the system.” He is romantic in Girard’s sense of being beholden to the modern Western fantasy of individualism. Yet on the other hand, Campbell also taps into the power of romance, in the sense of the medieval genre of hero stories, to form individuals by calling them away from the mimetic mob through conversion to a new pattern of desire, one formed on positive, non-conflictual models of transcendence from the finite to the infinite world.

Driving out to Iowa was a small journey into the special world for me. A larger one is participating in communities, like Blue Ocean Faith and like COV&R, that can help people undergo conversion to the infinite life of the Trinity. (For a mimetic approach to college as potentially such a community, see the commencement address I got to give at my college last August.) On my way home, I started listening to Jane Eyre, and that too seems like a story of conversion from the ordinary world of rivalry and resentment to the adventure of mercy and long-suffering love.

Does this essay on Blue Ocean Faith remind you of another example of how Mimetic Theory is being engaged by a community (religious, academic, secular, etc.)? To share a story in a future issue of the Bulletin, please contact the editor, Curtis Gruenler.

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the book review editor, Matthew Packer.

René Girard and Raymund Schwager:

Correspondence 1974–1991

reviewed by Grant Kaplan

René Girard and Raymund Schwager: Correspondence 1974–1991, edited by Scott Cowdell, Chris Fleming, Joel Hodge, and Mathias Moosbrugger, translated by Chris Fleming and Sheelah Treflé Hidden. Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. xiv + 218 pages.

René Girard and Raymund Schwager: Correspondence 1974–1991, edited by Scott Cowdell, Chris Fleming, Joel Hodge, and Mathias Moosbrugger, translated by Chris Fleming and Sheelah Treflé Hidden. Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. xiv + 218 pages.

The English translation of the recently published letters between Girard and Schwager represents an important and exciting resource for scholars of mimetic theory. The correspondence offers an insider’s peek into many of the key developments in the thought of both Girard and Schwager. This review comes in two parts. The first part discusses some of the more interesting ephemera, while the second part takes up the impact of the letters on the debate about where mimetic theory fits into the theological conversation.

Reading the correspondence confirms the classic saying: plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. The correspondents complain about department politics, lack of funding, bad reviews, a university eager to push professors into new technology, and an academic climate hostile to an honest and transparent discussion of ideas. On the final point Girard notes, “It would be hard for you to imagine, I think, to what extent university life […] is profoundly closed to research such as ours” (34). One can scarcely foresee how the author of such claims would eventually be inducted into the Académie Française.

The René in the letters is a deeply human figure: quick to express thanks for Schwager’s friendship and unfailingly gracious. The letters afford a glimpse into the life of a family man who relishes having his adult children home for the holidays, and who also shares his excitement over the promise that an IBM processor holds for new writing projects. A 1983 letter states, “You can work at any time on any part of the text, in all directions, add, delete, modify, correct as much as you want” (125). Maybe the last Luddite in Silicon Valley was not such a technophobe! Likewise, Schwager comes across less as a theologian whose work would be the subject of future dissertations, and more as a struggling mid-career academic, frustrated by a lack of reception of his work. Schwager even doubts whether he has led a purposeful life, confessing in 1985, “I wonder more and more, as the years pass quickly, if I have made of my life everything I could have” (145).

The epistolary exchange offers very little commentary on current events. They rarely talk Cold War politics, and despite a flurry of letters in 1978–79, no mention is made of the two papal elections in 1978. Perhaps this is due to a certain tact between a Swiss Jesuit working in Austria and a French exile in America. On the side of Girard, an underlying cultural pessimism emerges, making Battling to the End seem like a logical development rather than a rupture. After reading an interview with Ratzinger, Girard admits his fundamental agreement about the aftereffects of the Second Vatican Council. He continues, “In America, as in France, I have the impression of a veritable dissolution of the church” (147). In his next letter he writes, “American [Catholics] are intoxicated with Americanism and confidence in modern society. While often, the Protestants, if they are not fundamentalists, have more distance and awareness of the cultural decay advancing more or less everywhere” (149). Schwager did not seem to share the same pessimism, and may have elided some of these issues for the sake of focusing on the matters most central to their friendship.

These letters will serve to nuance the discussion about how mimetic theory fits into the (especially Catholic) theological conversation. Girard did not have any training in theology, and was not initially cognizant of the difficulties that certain aspects of his thought, especially about sacrifice, would pose for traditionally-minded theology. Midway through the correspondence, Girard begins using phrases like “orthodoxy” and referencing different theologians he is reading or hoping to meet: de Lubac, Balthasar, Maritain, and Ratzinger being the most prominent. We also learn that Girard was invited to an intimate conversation with John Paul II on his papal visit to France in 1980 (90). Schwager, no doubt, was essential for bringing Girard up to speed and raising his awareness about how much was at stake. Although the 2014 issue of Contagion contained several articles on the place of the letters in the evolution of Girard’s thought on sacrifice, a first-hand look at the evidence still provides a thrill. The letters do not tell the whole story—some key letters are missing, and we have no transcripts from the occasional face-to-face meetings—but Schwager, in ultra-Jesuit mode, managed to change Girard’s mind while making Girard think he had arrived at that point on his own. That is a slight exaggeration, of course. It can now be confirmed that, although Girard influenced Schwager initially, they related to one another as peers, and Girard learned plenty from this relationship.

Toward the end of the correspondence, several letters treat the question of the natural desire to know God, a question with a long history in Catholic theology, but of little interest elsewhere. Girard’s fixation on the transition from animal to human culture made it difficult to imagine, within this framework, a pre-lapsarian setting for the first human beings. This has led many to conclude that mimetic theory naturalizes sin. Yet a 1991 letter from Schwager on the intersection of natural desire and the fall made a deep impression on Girard: it is the only extant letter on which Girard scribbled notes and underlined (177). Here Schwager gestures toward the difference between Girard and de Lubac. After offering a few possible directions, Girard admits, “I have no fixed view, and I’ll go along with your view, because I don’t operate as well with abstract concepts as I do intuitively” (180). This sentence should be a warning for any theologians hoping for conceptual clarity from Girard!

There is also a spiritual dynamic between the two. In an early letter Schwager writes, “I thank God in my prayers that he has given you this wisdom. At the same time this prayer is ‘the means’ for me to avoid falling into an absurd rivalry by taking you as model” (33). Lest there be any confusion, academics simply don’t talk to each other like that. Repeatedly the two mention prayer. Girard makes personal conversion paramount: “True knowledge is always knowing that we persecute Christ” (131). The profound consequences of mimetic theory for social science did not, for these two most important exponents of mimetic theory, eclipse the abiding need for self-examination and conversion.

Regarding production, the team effort at translating and editing the letters paid off. The editorial touch is just right, and the translators do the best possible job of preserving but making intelligible Girard’s occasionally grammar-free sentences. The superb index will prove immensely helpful for those looking to track down comments about a particular figure or topic. The book is a winner and we can hope that a paperback will appear soon.

The One by Whom Scandal Comes

reviewed by Matthew Packer

René Girard, The One by Whom Scandal Comes, translated by M. B. DeBevoise [Celui par qui le scandale arrive, 2001]. Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. Michigan State University Press, 2014. 139 pages.

René Girard, The One by Whom Scandal Comes, translated by M. B. DeBevoise [Celui par qui le scandale arrive, 2001]. Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. Michigan State University Press, 2014. 139 pages.

Any readers overwhelmed by the recent, rich outpouring of work in mimetic theory may find one of René Girard’s last translated books, The One By Whom Scandal Comes, to be the book they’ve been waiting for. It is, as Girard himself writes, “above all an account of the present state of research I’ve been conducting for more than forty years now.” Despite its appearing originally in 2001, well before Battling to the End, and despite some of its central ideas having long percolated through from the European conversation, we have here still a fresh, full, and wide-ranging survey in English of what Girard considered “all the most controversial points of mimetic theory.” As one would expect, it’s a brilliant, finely translated, and urgent read.

In the opening chapter, “Violence and Reciprocity,” one of three important essays in a section called “Against Relativism,” we are reminded of how endless the permutations of mimetic rivalry are; how central reciprocity is to them all; and how patiently and persistently Girard sought to illustrate the problem’s core and its variety. In the case of apparently insignificant rituals, like handshaking, even the slightest snub or misunderstanding can, through “small symmetrical ruptures,” turn a relationship sour. In some situations, “individuals who just a moment ago were exchanging pleasantries are now exchanging perfidious insinuations. And soon they will be exchanging insults, threats, punches, or gunshots…without reciprocity ever being disturbed.” In contrast to much of his earlier work, Girard is explicit in this chapter about applying mimetic theory and points to the Gospels as “the only texts that fully recognize the mimetic character of human relations.” In reading Matthew 5:38-40 (on turning the other cheek) he explains that “violent persons must always be disobeyed, not only because they encourage us to do harm, but because it is only through disobedience that a lethally contagious form of collective behavior can be short-circuited.” Because of its clear examples and balance of problem-and-solution, this chapter could well serve teachers and others looking for a good introduction to mimetic theory.

In “Noble Savages and Others,” Girard revisits the ethnological field he explored to write Violence and the Sacred and laments that, although the end of the colonial empires and the horrors of the twentieth century wars have forced Westerners to reflect on their own violence—certainly a kind of progress—research in the anthropology of religion has come to a standstill. Part of the problem has been a rivalry and historical alternation between primitivists and Occidentalists—between Western, multiculturalist self-criticism and Western self-adulation, twin traditions together hiding a darker truth. Both perspectives divide humanity in two, Girard argues, both attributing violence to the other part of humanity. Where the anthropologists like J. G. Frazer found scapegoating and violence in primitive culture but not in the modern, idealized West, multiculturalists “today have managed to see what Frazer missed…a world full of more or less hidden victims.” But multiculturalists, at the same time, “fail to see that in the archaic world there was the same type of victim, the same scapegoat.” On both sides blindness obscures “the fact that all cultures, and all individuals without exception, participate in violence”—a discovery that mimetic anthropology doesn’t avoid, and which Girard, again, attributes to the illuminating power of the Gospels.

COV&R readers might be most interested in chapter three, “Mimetic Theory and Theology,” an essay written in honor of Raymund Schwager. In it, Girard clears up the misunderstanding about his own restricted earlier sense of the term “sacrifice,” often associated with his “non-sacrificial” reading of the gospels in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of World. “What was it,” Girard asks here, “that prevented me from seeing Jesus as a scapegoat who sacrificed himself for mankind? What was it that stopped me from taking the step that Schwager took at once?” For one, he was keenly aware that traditional definitions of the Passion in terms of sacrifice would only help arguments likening Christianity to an archaic religion. And for Girard, of course, a great gulf separates the two kinds of sacrifice seen, on the one hand, in Christianity and, on the other, in older, myth-infused rituals: a self-giving sacrifice on the one hand, in contrast to an offertory sacrifice to a bloodthirsty deity on the other. He says of his adamancy then that he wished only to “dispel among non-Christians, and today among Christians themselves, the equivocation perpetuated by the ambivalence of the term ‘sacrifice.’” In the judgment of Solomon, he says, we can see that the good prostitute’s self-sacrifice—giving up the rivalry over her child to save the child—is still a kind of sacrifice, but it means forgoing violence. And in eventually agreeing with Schwager on the broader, encompassing use of the term, he points out that “between the violence of human origins and schema of Christian redemption, one notices a symmetry…As against imperfect sacrifices, whose efficacy is temporary and limited, there is the perfect sacrifice that puts an end to all the others.” In retrospect, perhaps Girard’s self-admitted error concerning the term—or his early insistence on its use—may actually have helped propagate a key concept of mimetic theory. Certainly it’s a question to consider further, in light of both this key essay and the recently published correspondence between Girard and Schwager.

The second half of The One By Whom Scandal Comes is a long conversation between Girard and the Sicilian cultural theorist Marie Stella Barberi and covers nine topics, each given a short chapter. The first, on I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (then just published), emphasizes the main message of that work, generally understood, that the sources for mimetic theory are the gospels and the Old Testament. Girard’s earlier claim to the authorship of mimetic theory (in his first two major works) and later concession to its origin being in scripture, seem to be widely known now. Also addressed is the compositional problem of I See Satan Fall, where instead of being able to work chronologically through the biblical story, the revelation of scapegoating in the gospel texts was necessary for going back to read the earlier, unrecognized scapegoat mechanism. In the end he suggests, perhaps the best way to approach the book is as a thriller. “All of the pieces of the puzzle are given at the beginning, but it is only at the end that it becomes clear how they fit together.” He stresses here, too, his reading of Matthew 12:26: Satan used to cast out Satan by means of the victim mechanism, but after the revelation of Christ, he loses the power to do this. On whether Satan is a real being, “I follow traditional medieval theology on this point, which refuses to ascribe being to Satan.”

Another chapter concerns the central question of scandal. Barberi writes that scandal, “the most typical of mimetic relations, glorifies the ambivalent character—both attraction and rejection—of human desire.” We see it clearly in the Passion, where the disciples are drawn to Christ but then abandon him, as Peter alone realizes. This revelation itself, Girard argues, is impossible without Christ, since the mechanism “either operates on the world and unites everyone, so there is no one left to reveal it; or it does not operate and there are people left to reveal it.” The marvel of the revelation that occurred on the third day is that there was, first, unanimity established: “everyone united against Jesus, even his disciples.” The delay of the Resurrection, then, “allowed the disciples to understand what was happening. The unanimity of persecution began to unravel: the Holy Spirit gave the disciples the power to separate themselves from the crowd and to contradict it. This is why the Resurrection must be considered a revelation.”

Readers wishing to trace Girard’s understanding of the Gospels’ revelation could look carefully at Mark’s account, “the Gospel of the absolute scapegoat…[which is] incomparable in its ability to reveal mimetic relations.” Note, for example, in Mark, both thieves on the cross are hostile to Jesus, but they’re not in Luke; in Mark there’s no exception to the violent unanimity. We do need all four accounts, Girard insists, but with Mark “there can be no mistake: before the Resurrection, the disciples did not utter a single word that was not foolish…It is a portrait of humanity prior to Christ’s revelation.” We are reminded in this chapter also that further analysis can be found in the latter part of Girard’s 1986 study The Scapegoat.

Further on, Girard interprets John 17:9, “I Do No Pray for the World” (the title of another chapter) in similar terms: Jesus, in other words, is not praying for the world founded on the scapegoat, since the world has now been deprived of the “emissary victim.” So, asks Girard, what will people do? Since the old sacrificial system is finished, after Christ, the decomposition of this system follows—not instantly as the early Christians assumed, but gradually—in a manner demanding a sort of apocalyptic thinking: not the “wild talk” of final days, but an attending to what has been revealed by the Gospel. Girard wonders here, for example, what creative possibilities, what aspects of life formerly constrained by the sacrificial system may yet flourish: “other domains of knowledge, other ways of living. Everything that the Passion undid in the cultural sphere might well be an opening, an extraordinary source of enrichment.”

But he also keeps in mind “the signs of the times” (Matt. 16:3), and in two further chapters, on the church and on the “Stumbling Block to Jews, Foolishness to Gentiles,” he highlights a few key contemporary elements. Because of its universalism, Christianity itself “now is the only possible scapegoat, and therefore the real unifying factor of world.” But he also points to the importance of the historical “braking force” known as katéchon, as well as the reality that, “in order to prevent violence, we cannot do without a certain amount of violence”; Girard makes plain he’s no pacifist. “What is the weight to be given to sacrifices in a world in which the truth has been revealed? This is the modern predicament”—one with no easy solution, given the “extremely complex relationship between politics and theology.” Girard also briefly mentions here the work of Carl Schmitt and Alexis de Tocqueville, as well as Jean-Pierre Dupuy and Paul Dumouchel’s collaborative work on the modern economy, a katéchon “plain to see.”

Three of the final chapters explore scientific questions. One about hominization foregrounds the Christian and Darwinian thinking prominent in Girard’s work since Things Hidden, but that’s a theme treated more thoroughly elsewhere, and since then, of course (in Evolution and Conversion, especially, and in the work of Pierpaolo Antonello and Paul Gifford). In a chapter on Claude Levi-Strauss, anyone unfamiliar with how Girard moved in the 1960s from literary criticism to anthropology will find fascinating Girard’s confession about his admiration for Levi-Strauss—coupled with a lucid critique of Levi-Strauss’s structuralism, “the dominant perspective of the second half of the twentieth century.” In “Positivists and Deconstructionists,” Girard rejects Popper’s claim that a scientific theory needs to be falsifiable and insists on the value of “incontrovertible evidence,” along with the necessity of facts and interpretation, both, for serious research. Especially unsettling here is Girard’s observation that reason depends on social stability for its benefits to be shared; otherwise, “the informative function of reason has no effect on the crowd, which is governed instead by the scapegoat mechanism”—a dynamic seen in the umimpeded circulation of fake political news during the recent U.S. election.

In the closing chapter, on how mimetic theory should be applied, Girard first insists the ideas ought to become obvious, “because they are obvious!” But he’s ambivalent about specific goals. Assuming a proper mimetic research method develops, he “wouldn’t dare go so far as to tell people what to do with it,” though he does hope (in the book’s introduction) that we have here a line of inquiry that will “never be exhausted.” At the same time, he insists that to think merely in terms of grand concepts, “devoid of human feeling,” misses the point. He is quite aware of his own mimetic tendencies, which have motivated his writing and projects, and ultimately gives the advice to refrain from rivalry. Given the world’s fragility seen in terms of mimetic theory, furthermore, he concludes “religious faith is the only way to live with this fragility.” In sum, The One by Whom Scandal Comes is a key statement of Girard’s later science, essential reading.

God’s Gamble: The Gravitational Power of Crucified Love

reviewed by Simon De Keukelaere

Gil Bailie, God’s Gamble: The Gravitational Power of Crucified Love. Angelico Press, 2016. 384 pages.

Gil Bailie, God’s Gamble: The Gravitational Power of Crucified Love. Angelico Press, 2016. 384 pages.After his widely read and influential Violence Unveiled, many readers must have been waiting for Bailie’s new book: very soon after its publication God’s Gamble became the number one new release in its category on Amazon. Bailie’s great new book proposes an exciting synthesis of René Girard’s anthropology and Hans Urs von Balthasar’s theology with the outer ends and the “center” of history as its main focus. “Christianity is not one of the great things of history,” Bailie approvingly cites De Lubac; “it is history that is one of the great things of Christianity” (115). Likewise, Glenn Olsen: “A linear history moving towards a goal only appeared historically with the Judeo-Christian tradition” (111). It is impossible to summarize Bailie’s grand project here, yet I will try to pinpoint its main ideas and conclude with a word on the reflection and debates this book will no doubt elicit.

Bailie’s project is a Catholic one, referring to its literal meaning, i.e. universal. Is there a universal history or true story that gives meaning to our individual and collective stories? A story that is important for each human being? The refusal of such a universal narrative seems to be a “dogma” of our times. Yet a lot is at stake. Already in the first chapter Bailie again demonstrates his ability to let non-academic and academic texts mutually illuminate each other. God’s Gamble opens with an anecdotal essay from The New York Times Magazine. Journalist David Samuels autobiographically glosses over one more relational break-up. In search of deeper causes he writes: “Why bother? Why get married? What are families for?” (2). The journalist continues: “Coherent narratives, the stories that tell us who we are and where we are going, are getting harder and harder to find” (5-6). What if, Samuels asks, “the freedom to rearrange reality more or less to our liking is the only freedom we have?” (6)

Where are the stories that tell us “who we are and where we are going”? For Bailie this is an urgent question, and he draws from both anthropology and theology to find an answer. He begins with the first letter of the universal story, the Alpha, and looks for traces at the beginning of human history. Thus the second chapter’s title is: “The Emergence of Homo Sapiens.” Here Bailie turns to Girard and uses striking, brief formulae to bring us close to the core issue of God’s Gamble. In his words, “Girard has explicated the cruciformity of culture” (22; italics added). Indeed, “the first rudimentary forms of human culture came into being in the midst of an event that is structurally identical to the Passion Story” (21). This, in turn, brings us to the central role of the Crucified One in human history. Here Bailie wants to bring together great insights from both anthropology and theology (“Toward a Theological Anthropology”), yet he wants to avoid “maladroit efforts to retrofit theological truths in the interest of aligning them with what Girard calls ‘mimetic theory’…[indeed], this collaboration will require both mutual respect and—most of all—patience” (37).

It is impossible to convey the richness of Bailie’s thought on the beginning of history. The same is true for the Omega that is so closely linked to the Alpha. The loving self-gift humans are made for points to their ultimate vocation: entering Trinitarian love, a heavenly “nuptial” mystery. Yet the door is Christ, the “Lamb slain from the foundation of the world” (Rev 13:8), the true center of human history. Christ is the Alpha, but also the Omega. At the end all will see the Victim and his wounds. “Behold… every eye will see him, even those who pierced him. All the peoples of the earth will lament him. Yes. Amen. ‘I am the Alpha and the Omega,’ says the Lord God, ‘the one who is and who was and who is to come, the almighty’” (Rev 1:7-8). The great question that haunts Bailie’s Omega-Christology is whether all human beings will eventually answer Christ’s invitation to accept his unappreciated love and enter into the Trinitarian communion all secretly aspire to in the first place. Thus, “what is at stake in the apocalyptic war is precisely God’s gamble: whether the divine intention of bringing each and every creature made in the image and likeness of Trinitarian Love into full communion with the Trinity will succeed or be thwarted by human willfulness” (267). Indeed, without freedom there is no real love. To explore this question, without of course giving a definite answer, Bailie mainly turns to Balthasar’s eschatology—but not without very personal and provocative notes.

One of the most beautiful chapters of the book is the last, on the Eucharist, “Abide with Us.” Christianity did not leave us with the alternative between the decomposing ancient (“pagan”) sacred and the secular… since “it grows clearer by the day that the secular is utterly incapable of replacing the sacred as a cultural foundation” (329). The good news is: there is a “sacramental alternative to the primitive sacred” (331). “The world has shifted on its true axis, the Cross of Christ, and henceforth history will consist of the long, slow, and often tragic reorientation from a (primitive) sacred to a sacramental form of religious meaning and social solidarity” (330). Christ, the Word that became flesh, did not write anything; the “heart of Catholic Christianity” is not a book (as important as the Bible is) but the “Eucharistic sacrament of Christ’s abiding” (332). With its crystal-clear cannibalistic innuendo (John 6) the Eucharist harks back to the (fallen) origin of humankind. At the same time it refers to the eternal “wedding banquet” to come. It also makes Christ’s sacrifice, his ultimate loving self-gift, present right now, today. Bailie writes: “The ever-contemporaneous story relived at each celebration of the Lord’s Supper in the upper room and death on Golgotha is the narrative Rosetta Stone for deciphering the meaning of reality itself, the human vocation as such, and the nature and purpose of human history” (352).

God’s Gamble is a very impressive, inspiring, and beautiful achievement that is impossible to summarize in a brief review. It will no doubt also elicit fruitful debates, for instance on Bailie’s ideas on hell. Bailie fully endorses Balthasar’s view summarized in Dare We Hope, but goes beyond Balthasar’s famous explorations of the outskirts of Catholic doctrine, suggesting there might be some kind of “post-mortem ‘conversion’” (255), something Balthasar explicitly rejected. Since Bailie insists on the importance of the magisterium, this might come as a surprise. At times Bailie seems to suggest more than one can know without some special revelation—and at times less, as is probably the case here: “As to whether human freedom is capable of sustaining a sufficiently rebellious spirit to thwart the redemptive will of God in Christ, we must remain agnostic” (299). Canon 4 of the Council of Trent’s Decree on Justification seems to rule out this “agnosticism.” Indeed, speaking of God’s saving grace in Christ, i.e. of the “grace of justification,” one cannot say that “man’s free will… cannot refuse its assent if it wishes [neque posse dissentire, si velut]” (Denzinger-Hünermann 1554).

In the past the Church certainly often had a still very “sacrificial” (in the ancient sense) way of understanding the doctrine of hell. This caused quite some indignation and excellent reflection in recent theological history. Yet, could it not be the same with the doctrine of hell as with the doctrine on resurrection, sacrifice, and the Eucharist, that were often understood in a very “sacrificial” way too? As our history influenced by Christianity helps to purify the image of God and helps us recognize that he is only Love, those doctrines do not get less real at all. The contrary is true. If God is truly Love, human freedom and human responsibility are not diminished, but augmented. It seems Christ stands at the door of every human conscience, be it in very hidden or more explicit ways, and humbly and gracefully knocks (Rev 3:20; So 5:2). Yet he will never coerce the human soul. No doubt, Bailie would agree with this. We are looking forward to the ensuing theological debates. Bailie’s book is a good gamble indeed. A book to read and re-read.

Mimesis and Science: Empirical Research on Imitation

and the Mimetic Theory of Culture and Religion

reviewed by Brian Harding

Mimesis and Science: Empirical Research on Imitation and the Mimetic Theory of Culture and Religion, edited by Scott R. Garrels. Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. Michigan State University Press, 2011. xii+266 pages.

Mimesis and Science: Empirical Research on Imitation and the Mimetic Theory of Culture and Religion, edited by Scott R. Garrels. Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. Michigan State University Press, 2011. xii+266 pages.

René Girard was never shy about the scientific ambitions of his work. In part, this served to distinguish his work from those of other literary and cultural theorists he was often associated with, but there was more to it than mere rhetoric: Girard consistently dialogued with social science, especially anthropology. The volume under review, Mimesis and Science, continues and expands that dialogue, with a special focus on psychology, neurology, and related fields. The book is important for any student of mimetic theory (MT) who would like to know, in a nutshell, whether or not the “mimetic” interpretation of human psychology and behavior is borne out by empirical investigation. There are two dominant streams in the book. The first focuses on empirical evidence for Girard’s claims regarding the importance and ubiquity of imitation in human life. The second uses recent findings in cognitive science to critique, expand, or modify Girard’s account. Generally speaking, there is agreement that MT is, more or less, verified by recent scientific investigations although there remains room for refinement, critique, and further development.

Since Girard’s work is mainly received in the context of the humanities (literary theory, philosophy, theology) one might worry that the contributors would not have the necessary background in cognitive science and the social sciences. In this case, this worry does not apply. The contributors are highly respected figures in their respective fields and bring their authority to bear on MT. While some of the contributors will already be familiar to readers of this publication (Dumouchel, Dupuy, Oughourlian) some may be less well known. Here one can mention, among others, Vittorio Gallese (an authority on mirror neurons), Andrew Meltzoff (a leading developmental psychologist).

The book begins with a short essay by editor Scott Garrels that sketches the historical development of theories of imitation. The broad outlines of the theory will be familiar to readers of Girard, but Garrels is able to add a discussion of recent findings in the cognitive sciences. As he notes, these findings are largely consistent with the major claims of mimetic theory. The book concludes with an interview with Girard conducted by Garrels. The interview offers an overview of Girard’s thinking, and will be primarily useful for readers new to Girard’s work. Girard briefly comments on the relationship between his theories and cognitive science. The introductory essay and the interview mainly serve as bookends for the other essays in the volume. It is to those that one should turn for more in-depth treatments of the relationship between mimetic theory and cognitive science.

Apart from the bookend pieces, the text is divided into two parts. The first part is titled “Imitation in Child Development and Adult Psychology” and the second part “Imitation in Human Evolution, Culture and Religion.” In the first part, there are four papers; in the second part there are five, plus the aforementioned interview with Girard. In Part One we find papers by Oughourlian, Meltzoff, Dumouchel and Gallese. The Oughourlian paper is a revised version of a chapter found in his book The Puppet of Desire. The Dumouchel paper examines the interaction between mimesis and the emotions, arguing that while mimesis and emotions are quite different, there are a number of similarities, most notably that they both play a role in process by which an agent’s intentions are discerned by another and adapted to. The paper by Meltzoff summarizes the results of his research into imitation by infants and coordinates his findings with those of MT. This research refutes Piaget’s claim that infants do not imitate until they are at least eight months old. Meltzoff and his team showed that infants can imitate within hours of birth. In a separate paper, Gallese coordinates recent findings involving mirror neurons with Girard’s claims about triangular desire and mimesis more generally. Gallese concludes (on the basis of neurological findings, brain scans, and the like) that mimesis is a basic brain function that makes possible our social activities and competencies. Although William Hurlbut’s article appears in Part Two, it makes sense to mention his contribution here insofar as he offers a biological and evolutionary account of mimesis. Hurlbut suggests that humanity’s mimetic powers can be explained as a kind of “runaway evolution” whereby a helpful adaptation goes so far as to become dangerous. Mimesis is adaptive insofar as it aids in forming communities, but maladaptive insofar as it can lead to violence.

In Part Two we move away from psychology and cognitive science in the strict sense to embrace broader topics: evolution, religion, and culture. The latter two are the bread-and-butter of MT, and the first is being seen as increasingly more important. The essays in this part, however, do not merely repeat the findings of mimetic theory but place them in the context of other work in these areas. So, for example, in the first essay Ann Cale Kruger connects mimetic theory with the Cultural Intelligence Hypothesis (CIH). According to CIH, the human intellect is uniquely adapted to function in complex social contexts; by this CIH includes not merely cognitive skills, but empathy, the sharing of intentions and behaviours, and so on. Kruger deftly moves back and forth between CIH and MT, thereby highlighting important similarities and differences. Perhaps the most important difference is that CIH maintains that hominization is not the result of a scapegoating murder that resolves conflict (as in MT) but in cooperation for scarce resources. Although Kruger does not dwell on the issue, it seems to this reviewer to be of fundamental importance: if humanity is not built on the tombs of victims, then much of Girard’s cultural theory becomes questionable. Here the contribution of Melvin Konner is helpful; his paper defends the MT thesis regarding the violent sources of hominization, drawing from anthropology, archaeology, ethology, and related disciplines. What we know of the violence of early humans and their ancestors strongly suggests that whatever cooperation we may note was inseparable from violence and aggression; indeed, war joins violence and cooperation in a particularly bloody way. While this review is not the proper space for careful consideration of the evidence for either view, it is certainly worthwhile to note that, (a) in MT, while scapegoating violence is at the foundation of religion and thereby cultures, this original scapegoating murder occurs mainly in response to a crisis that threatens the social structure and as such seems to presuppose some kind of cooperation prior to the crisis; (b) this scapegoating is cooperative in nature insofar the blaming and killing of the scapegoat proceeds with unanimity. This suggests that cooperation and scapegoating are not mutually exclusive and that it might be possible to reconcile MT with the more cooperative view of hominization derived from CIH and related theories; here I would refer again to the thesis developed in Hulbert’s paper.

Early in his contribution Mark Anspach notes that there has been little effort expended in creating experiments that would test the claims of MT. There are a few reasons for this, one of them being the difficulty one faces when trying to create a simple testable hypothesis out of such a large and sweeping theory. His paper is devoted to getting around this problem by reducing MT to a simple schematic model that then can be used in experiments and social science research. There are four elements to this model, which I will present in an even more radically schematic form: (a) acquisitive mimesis leads to violence; (b) this violence is imitated and spreads; (c) the snowballing mimesis eventually turns against a common enemy; (d) subsequent rituals attempt to reproduce the pacifying effects of (c). Once Anspach has this schema in hand, he then applies it to a number of empirical studies in a kind of qualitative meta-analysis.

The final essay in the volume begins on a cautionary note. Jean-Pierre Dupuy admits at the outset that the convergences between MT and cognitive science are striking, but nevertheless maintains that one should hesitate before claiming that cognitive science offers scientific proof for the tenets of MT. This, Dupuy argues, is due to fundamental differences between cognitive science and MT in how they model the mind. As Dupuy sees things, cognitive science assumes that desires follow from beliefs while MT separates beliefs from desire, seeing (at least some) desires as the product of a mechanism. Rather than adopt conclusions from cognitive science as its own, Dupuy suggests that MT turn to evolutionary theory (ET) for a better conversation partner. This is because both are more comfortable with the centrality of mechanisms, rather than subjectivity, in understanding human nature. As the paper continues, Dupuy provides his own version of what Anspach suggested: a schematic model of MT that is then put in conversation with science, in this case, ET. MT, Dupuy argues, can be represented as path-dependent self-organizing systems whereby previous adaptations provide the basis for future ones, and complex systems emerge out of “noise.” The similarity with ET should go without saying.

I have only scratched the surface of the papers in this volume. Any student of MT with an interest in the empirical sciences should read the book. In a sense, this book can be taken as a prequel to the more recent volumes that use MT to engage with the sciences, i.e. Can We Survive Our Origins, How We Became Human, and the long interview with Girard published as Evolution and Conversion. The essays in this volume combine the sobriety and audacity of MT with the precision and evidence of well-done scientific studies.

The Sacrifice of Socrates: Athens, Plato, Girard

reviewed by Brian Harding

Wm. Blake Tyrrell, The Sacrifice of Socrates: Athens, Plato, Girard. Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. Michigan State University Press, 2012. xix + 189 pages.

Wm. Blake Tyrrell, The Sacrifice of Socrates: Athens, Plato, Girard. Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. Michigan State University Press, 2012. xix + 189 pages.

One could offer a fairly simplistic description of Wm. Blake Tyrrell’s The Sacrifice of Socrates by saying that it offers a Girardian reading of the trial and death of Socrates as described in Plato’s dialogues. Although I will have occasion to add more complexity later, the simplistic description has the advantage (I hope) of immediately grabbing one’s attention. René Girard’s occasional references to Plato are typically critical; Plato, he charges, did not understand or appreciate acquisitive mimesis. One finds these points made in Violence and the Sacred and in the fairly late essays collected in The One by Whom Scandal Comes. Girard’s fairly constant attitude towards Plato can be contrasted with his shifting interpretations of other Greek authors. Under the influence of Sandor Goodhart, for example, Girard came to believe that Sophocles was more aware of mimetic desire than he previously gave him credit for. However, Girard never discussed Plato with the same depth of attention that he did Sophocles. For a book to come along and offer a Girardian account of Plato is of more than minor interest.

Despite Tyrrell’s stated aim of contributing to Girardian studies he has a more positive evaluation of Plato than does Girard. Taking issue with the aforementioned claim that Plato had no awareness of acquisitive mimesis, Tyrell begins his study with a discussion of Greek honor and the contest system. Life in ancient Greece was a constant struggle to be the best, to imitate and supplant one’s models. Plato fails to discuss acquisitive mimesis, Tyrrell argues, because it was intimately familiar to his Greek audience. It is unsaid because it goes without saying. This claim, articulated and defended in chapter one of The Sacrifice of Socrates, forms the basis for the discussion in the following three chapters. The second chapter describes the victimary culture of ancient Athens. The third chapter focuses on the description of Socrates in Aristophanes’ Clouds, a text mentioned in The Apology as the source of the older and more dangerous accusations against Socrates. The fourth and final chapter offers a reading of the Platonic texts orbiting around the trial and death of Socrates: The Euthyphro, The Apology, The Crito and The Phaedo. In what follows, I offer more detail on each chapter.

Chapter One begins by placing Socrates’s elenchus within the context of the Greek contest system. According to Tyrrell, this contest system begins with a contest over prize but develops into a desire to completely displace and humiliate one’s opponents. The resonances with acquisitive mimesis and the conflicts it engenders should be clear. Socrates’s elenchus appears to his auditors as a kind of contest: an interlocutor claims to have knowledge of X, and Socrates – through his questioning – shows that he does not, in fact, know X. In the eyes of the Greeks, Socrates defeats his interlocutors in a contest. But, Tyrrell continues, Socrates’s oft-repeated claim of ignorance serves a double function: on the one hand, it keeps violence at bay because Socrates doesn’t lord his victory over the interlocutor, but on the other, it creates a crisis of difference insofar as the Q-and-A slowly dissolves the differences between Socrates and his interlocutor. By the end of the dialogue, neither claims to have knowledge of X. The Socratic elenchus creates a small-scaled mimetic crisis. Whence it is not surprising (but often overlooked) that threats of violence against Socrates occur fairly regularly in the dialogues.

Chapter Two describes the victimary culture of ancient Athens and Greece more generally. Particularly of interest to readers of Girard will be the discussion of the pharmakos ritual, whereby prisoners (maintained at the city’s expense) are periodically tortured and killed by the city at large. Tyrrell points out that prior to their torture the pharmakoi were housed in the Prytaneum; readers of The Apology will recognize this place from the second speech of Socrates. The Prytaneum functioned as the central hearth for Athens and was used to house foreign dignitaries and to reward citizens who were worthy of great honor. In The Apology, when he has been asked to recommend a punishment, he recommends being given free meals in the Prytaneum. The chapter concludes with a short discussion of “Socrates as pharmakos” that builds off the Prytaneum remark and prepares the way for future discussions.

Chapter Three offers a close reading of Aristophanes’ Clouds. According to Tyrrell’s reading, Aristophanes offers us a “Satanic Socrates” who seduces others into violating prohibitions and taboos thereby precipitating a mimetic crisis. The Clouds tells the story of a dull-witted father and son, who enroll as students of Socrates to escape paying debts. Socrates teaches them how to argue out of debts, and perhaps more importantly, that there is no need to worry about divine retribution for dishonesty and other vices. The result of Socrates’s teaching is disastrous: it breaks down the hierarchical relationship between father and son, culminating in the son beating the father and arguing that one can licitly beat one’s mother. Aristophanes’ Socrates unleashes desire, destroys difference and is ultimately killed: the father, Strepsiades, gathers the town together and sets fire to Socrates’s house. Burning Socrates alive restores the differences his teachings collapsed; The Clouds readily lends itself to being read in terms of mimetic theory.

Chapter Four is the most complicated and subtle chapter in the book; Tyrrell’s reading of The Apology distinguishes between twenty different voices. He argues that Plato’s depiction of the trial and death of Socrates both victimizes and absolves Socrates. While maintaining that Socrates was innocent of the charges levied against him (corrupting the youth and not believing in the gods of the city), Plato nevertheless uses the death of Socrates to condemn the demos and to found his own philosophy as an alternative (94). Socrates’s reference to the Prytaneum is discussed here at length in some very illuminating pages. As already noted, it was where the pharmakoi were fed, but it was also made available to Olympic victors; Tyrrell notes that the public care of the victors was meant to domesticate them and prevent the victor’s kudos from tyrannizing the population. So, he concludes, “Plato sets up Socrates as a tyrant” (132). This is an important and suggestive point for any student of Plato: the problem of tyranny is central to The Republic and Socrates’s claim that only the wise should rule could easily sound tyrannical to the people of Athens (133). Plato (according to Tyrrell) is well aware of the danger Socrates presents to Athens: to the extent that Plato’s Socrates seeks to lead men away from mimetic rivalry (125) and to the extent that Athenian culture is defined by such a rivalry (as argued in Chapter One), Socrates’s goal is nothing other than a fundamental transformation of Athenian culture. One wonders if this claim doesn’t undermine the purported innocence of Plato’s Socrates and suggest a similarity with the destructive effects of Aristophanes’s version of the man. In fact, even in Plato’s texts, the innocence of Socrates is less straightforward than it is often taken to be. Whether or not Socrates is guilty depends on whether it is right that traditional Athens be destroyed (139). One way of taking the bulk of Plato’s political philosophy is as arguing that traditional Athens was severely deficient on a number of points and thus, Socrates was right in undermining it. In this way, Socrates’s death at the hands of the Athenians becomes the founding murder of Plato’s philosophy (147). Indeed, in The Phaedo, Socrates’s death no longer appears as an end but a beginning: the beginning of his soul’s escape from the body, and the beginning of philosophy more generally. It transforms Socrates into an external mediator the imitation of whom releases one from quotidian mimetic rivalries.

Tyrrell’s reading of the trial and death of Socrates is fascinating and provocative. It raises as many questions as it answers. To conclude I will mention a few further questions, not as criticisms but as potential lines for future research. First, can this method of reading be extended to other Platonic texts, e.g., The Republic? Second, while Tyrrell convincingly shows that Plato is aware of the sacrifice of Socrates, is Platonism equally aware? Is the sacrifice forgotten in later texts or by later more metaphysically inclined Platonists? Third, does this re-evaluation of Plato entail a re-evaluation of Girard’s criticisms of Plato and philosophy more generally? Fourth, how does this re-reading of Plato affect our interpretation and evaluation of Platonic political philosophy? Fifth, given the illuminating comparisons Tyrell draws with Girard’s reading of the passion narratives, does this reading of Plato force us to reconsider Girard’s claims about the uniqueness of the Bible’s preference for victims? Answering any of these questions would take a book in its own right, and one ought not to expect answers from Tyrrell’s book; it is to the credit of The Sacrifice of Socrates that they can be formulated.

Disturbing Revelation: Leo Strauss,

Eric Voegelin, and the Bible

reviewed by George A. Dunn

John J. Ranieri. Disturbing Revelation: Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, and the Bible. University of Missouri Press, 2009. 288 pages.

John J. Ranieri. Disturbing Revelation: Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, and the Bible. University of Missouri Press, 2009. 288 pages.

In Disturbing Revelation, John J. Ranieri takes a critical look at the place of the Bible in the thought of two important twentieth century political philosophers, Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin. Both were driven into exile by the Third Reich—Strauss was a German Jew, while German-born resister Voegelin was forced to flee Vienna—and both eventually settled in the United States. Each developed a highly original interpretation of the history of the West foregrounding the relationship between philosophy and revelation. Unsurprisingly, their reflections on modernity were pervaded by a profound sense of crisis, and for each, the biblical tradition played a central role in his story of how the West had come to its present impasse.

After first outlining the approaches taken by Strauss and Voegelin to reading the Bible, Ranieri devotes chapters to each philosopher’s engagements with the biblical text itself and then to each one’s account of the formative role of the biblical text on modernity. Believing that the biblical tradition has played an indirect role in nurturing the political extremism of the twentieth century, Strauss and Voegelin both contrast the Bible to the classical tradition of political philosophy exemplified above all by Plato, which they believe exhibits a measure of balance and moderation that they find lacking in the Bible. Although not named in the title, there is another famous reader of the Bible quietly present throughout the book—René Girard. Only in Ranieri’s concluding chapter does Girard confront Voegelin and Strauss directly, but to those who know Girard’s work, it will be obvious that his insights inform every page of Ranieri’s study.

Ranieri asks, provocatively, whether philosophers can do justice to the Bible. His answer, ultimately, is a resounding no. This conclusion should come as no surprise to those who are familiar with Girard’s work. Apart from a few highly polemical essays on Nietzsche, Girard never gave sustained attention to the Western philosophical tradition, yet his scattered references to Plato, Heraclitus, Heidegger, and other philosophers are almost uniformly negative. Ranieri repeats and endorses Girard’s charge that philosophy has always been complicit in scapegoating violence or at least in humanity’s longstanding cover-up of the founding murder, which was finally exposed by the biblical revelation.

Ranieri’s book is important, therefore, not only because it offers a deeper understanding of Strauss and Voegelin and their perspectives on the Bible, but also because of the contribution it makes to a dialogue between philosophy and mimetic theory. Given limitations of space, I will focus mainly on Ranieri’s critique of Strauss, even though Ranieri spends more time on Voegelin. Strauss, in my opinion, is a much more important interlocutor for Girard. More than any other major contemporary thinker, Strauss has placed the tension between philosophy and revelation at the heart of his reflections. Moreover, Ranieri shows himself to be an especially good reader of Strauss, whose often enigmatic texts seem to have been deliberately crafted to veil his most heterodox thoughts to all but the most attentive readers. Ranieri thus takes a place alongside such other distinguished readers of Strauss as Laurence Lampert and Heinrich Meier, who are skeptical of Strauss’s ostensibly agnostic accommodations to religious belief (see Lampert’s Leo Strauss and Nietzsche and The Enduring Importance of Leo Strauss; also Meier’s Leo Strauss and the Theologico-Political Problem).