Letter from the President

Jeremiah Alberg

International Christian University

On the morning that I was set to depart from Madrid, I felt that familiar sadness of another delightful annual conference coming to an end. I get to share a little in the ups and downs of the planning and preparation with the organizers. Some things work out; others do not; new ideas have to be tried; adaption is required. And then it happens, a new conference, not unlike the previous ones and yet not identical to them either. It has always struck me how much the place and the organizers affect the conference. Madrid, with its planners Ángel Barahona, David Garcia-Ramos Gallegos, and their staff, deeply marked the 2017 conference with warmth, hospitality and beauty. In one sense the outdoor banquet sort of captured it all: a lovely setting, superb cuisine, enchanting music, and very moving tribute to one of the giants of COV&R – Cesareo Bandera.

So I am deeply grateful for all we were able to experience there and I leave the reader to consult other articles in the Bulletin that will tell you more about its contents. Instead, I will write a little about topics discussed at the Board and at the Business Meeting.

First, we have clear plan for future meetings. As many of you know, next year’s conference will be held at the Catholic University of America in Washington D.C. from July 11th to the 14th. The organizer is Steve McKenna. In 2019 COV&R will return to one of its homes: Innsbruck, Austria. The organizer is Niki Wandinger. And in 2020 Andrew Bartlett has graciously offered to host our meeting in Vancouver jointly with GASC (Generative Anthropology Society & Conference).

Second, you can read more about having the Philosophical Documentation Center take charge of our membership renewals in Martha Reineke’s column, but it has resulted in an increase in funds, which allowed the Board to authorize Steve McKenna to spend up to $2000 for advertising the 2018 conference. The Board will continue to evaluate ways of effectively using our resources to get our message to a wider audience.

Saving the most important till the end, we need to publicly thank Dietmar Regensburger and Keith Ross for their service as our European and North American Treasurers. Dietmar has served as an officer of COV&R longer than any other person. He has consistently kept the European branch of COV&R in the black and informed. His work with the bibliography of mimetic theory will continue. Keith was generous beyond words in helping us to keep our books balanced and bills paid. He has always been a steadying voice on the Board and we are grateful for all he has done.

Due to the restructuring of the members’ service, we are able to operate with just one Treasurer and to do away with the increasingly insufficient and inaccurate division between a European and a North American “branch.” So I am pleased to announce that Sherwood Belangia was elected to serve as our Treasurer for the next three years. Sherwood is long-time member of COV&R, an outstanding scholar of not only mimetic theory but also Plato’s philosophy as well as being president of his own company. I am personally grateful for his generosity in accepting this position.

As for other positions, William Johnsen was reelected to the position of Editor of Contagion and the MSU Series, Violence, Mimesis, & Culture and Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory. We also want to thank Scott Cowdell, Sheelah Treflé Hidden, Mathias Moosburger, and Thomas Ryba for their years of service on the Board. We welcome Roberto Solarte, Wilhelm Guggenburger, Ángel Barahona, and Marinela Blaj as new members.

Finally, I was reelected to another term as president. Most of the things that I am most proud of these last two years are due entirely to the efforts of other people. Thanks to Martha Reineke I think that we have our membership list, renewals, and e-mail contacts in the best shape they have ever been in. Thanks to the efforts of Maura Junius, Curtis Gruenler, Carly Osborn, Suzanne Ross and others our website and this Bulletin have been updated and made more attractive. We will continue to push these kinds of efforts. I appreciate the widespread support that COV&R receives from its members.

Musings of the Executive Secretary

Martha Reineke

University of Northern Iowa

I join President Jeremiah Alberg in expressing profound appreciation to our hosts in Madrid, including Ángel Jorge Barahona, David García-Ramos, Ana González, and Blanca Millán for planning and hosting at Francisco de Vitoria University an outstanding annual conference. We had a truly international meeting: it is highly likely that the list of countries represented at the conference was longer this time than at any previous COV&R meeting. In addition to the outstanding plenary sessions and concurrent sessions, the common dining hall supported memorable conversations and networking among the participants.

Our hosts had planned an extraordinary cultural program as well, with the singular highlight of cante flamenco at the conference banquet. This auditory feast was a first introduction for many of us to a rich tradition that reflects the influence of traditional song, Muslim and Jewish chanting, and regional folk traditions of Spain. Our visit to the Prado museum included viewing paintings with profound mimetic implications including, most compellingly, Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (Ladies in Waiting), a painting that memorably lends itself to Girardian interpretation. In this work, the artist incorporates into the scene a mirror, in which Philip IV and Queen Mariana are ghostly presences. The mirror places both figures on our side of the canvas; as a consequence, the King and Queen look along with us at the scene Velázquez has painted. Indeed, returning our gaze from his position in the painting is Velázquez, who stands poised, brush in hand, before the canvas on which presumably he is preserving for all time the visages of the King and Queen.

Subject to diverse interpretations, from the perspective of mimetic theory, Las Meninas captures in stunning fashion the impending end of the Golden Age of Spain. Philip’s empire is collapsing around him. Yet Velázquez, whose paintings could have functioned solely as propaganda for Philip’s court (“fake news”), chooses instead to capture the moment in which the King is dispossessed of his position—and does not know it. Situated outside the frame alongside the ordinary viewer and visible only in a mirror, Philip, both there and not there, is made to attest to a crisis in representation, for which Velázquez’s composition rightly is acclaimed. But the painting, in disturbing the conventions of royal portraiture, also attests to unstable royal power, thereby alluding to Spain’s economic and political crises, and most especially to a metaphysical disease—an underlying crisis of desire. Here, with his novel mirror-work, Velázquez brilliantly exposes the true cause behind the downfall of empire.

So rich a landscape for mimetic theory did Spain afford us that I could go on at length, commenting not only on other paintings from the Prado but also on our visit to El Escorial, and on my own travels during the week before the conference to Avila, Salamanca, and Segovia. All provide productive opportunities for analyses grounded in mimetic theory. And all these experiences were made possible because of the generosity of our hosts who, in inviting us to come to Madrid, brought me to a country which had not even been on my travel wish list. Now, I want to return to Spain as soon as possible, to delve deeper into the remarkable heritage of art, architecture, geography, and religion in this amazing country.

Having returned home, participants in the conference will continue to benefit from their week of reflection and shared experiences in ways that bode well for the coming year. Thanks in no small part to the efforts of the Philosophy Documentation Center to enhance member communication, we have experienced significant growth in the organization this year. We are an energized community. Our web presence, including both a revised website and Bulletin, is stronger than ever. Curtis Gruenler, Suzanne Ross, Maura Junius, Matthew Packer, and Carly Osborne have worked hard to upgrade and update the visible face of COV&R, for which we are extremely appreciative. We are grateful also to Dietmar Regensburger for his ongoing work on the bibliography of literature on mimetic theory. Sometime this fall, the Girard database at Innsbruck will complete a successful migration to Tübingen, which should result in enhanced search capabilities for all of us.

The Board also approved two other avenues for outreach intended to strengthen the practice of mimetic theory. We passed new guidelines for conference planners to encourage them, where possible, to provide a platform for the sharing of undergraduate research at our summer meetings. And we also took initial steps to develop an online directory to graduate and professional programs at universities around the world. This directory will connect individuals wishing to study mimetic theory with individuals and institutions that can support their interests.

With an unsettled political climate in the US, next year’s meeting in Washington DC promises to be a timely and acutely needed opportunity to showcase the strengths of mimetic theory in illuminating and bringing to critical awareness the themes of “Politics, Religion, and Violence after Truth.” Jay and I very much hope that every COV&R member will put the meeting on their “must do” list for the year. We look forward to seeing all of you at Catholic University of America.

Editor’s Column: News and Prospects

Curtis Gruenler

Hope College

At its meeting in Madrid, the COV&R board decided, among other things, to make this Bulletin freely available. COV&R membership will not be necessary in order to access either new or past issues, whether on the COV&R website or at the Philosophy Documentation Center (PDC, which will soon include PDF versions of the recent, web-published issues). Members will continue to receive email notifying them that a new issue has been published. Members will also, of course, continue to receive Contagion and books published by MSU Press. By being openly accessible, the Bulletin can serve as outreach to non-members. So feel free to send links to pieces in the Bulletin to non-members and post them on the web knowing that people will be able to see them.

MSU Press update: Now that membership services are being handled by PDC, please contact them if you have not received books from the two MSU Press series that are included in COV&R membership, Studies in Violence, Mimesis, & Culture and Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory. Two books have been published so far in 2017 and sent to members: Violence in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock by David Humbert and Vengeance in Reverse by Mark R. Anspach. Anticipated before the end of the year is Mimetic Theory and World Religions, edited by Wolfgang Palaver and Richard Schenk.

Allied organizations: Elsewhere in this issue, you will find a report about this year’s meeting of Theology & Peace by its president, Susan Wright. We would welcome similar reports about other organizations or events involved with mimetic theory. If you would like to write something, please contact me. It would be great to have a report on the Raven Foundation’s 10th Anniversary Celebration, Oct. 21-22 in Chicago (register here).

New journal: A new journal called Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence devoted its first issue to the theme, “Mimetic Theory and Philosophy.” It begins with “René Girard and Philosophy: An Interview with Paul Dumouchel” and includes “Emmanuel Levinas and René Girard: Religious Prophets of Non-Violence” by Robert J. S. Manning, “Consilience, Abduction, and Mimetic Theory: An Epistemological Inquiry into René Girard’s Interpretation of the Oedipus Myth” by Marian Tataru and “Portrait of René Girard as a Post-Hegelian: Masters, Slaves, and Monstrous Doubles” by Andreas Wilmes. PJCV is also on Facebook. A call for papers by “young researchers and established academics” is available on the journal’s website. The deadline for the next issue is September 18.

Online publications: One of the pleasures of this year’s COV&R meeting was meeting Erik Buys, whose blog Mimetic Margins I had recently run across. Its “About” page includes a good list of other mimetic theory websites. I also recently saw two short Youtube videos on mimetic theory that are worth noting: René Girard’s Mimetic Theory in 4 Minutes and René Girard’s View of the Bible in under 5 Minutes. Please let me know about other online publications that might be of interest to COV&R members.

Call for papers: I am putting together a proposal for a theme issue of the journal Christian Scholars Review devoted to “The Promise of René Girard’s Mimetic Theory as an Interdisciplinary Paradigm for Christian Scholars.” Christian Scholars Review is sponsored by several dozen Christian colleges and universities in North America, including Hope College, where I teach. Its audience is academics of all disciplines who are interested in the integration of faith and learning, most of whom identify as evangelical Protestants but also including Catholic and mainline Protestant scholars. The aim of the theme issue would be to introduce mimetic theory to scholars in a variety of disciplines who are not familiar with it but might find it of interest for their scholarship and teaching and as people of faith. I would like to assemble a small group of scholarly articles that would show the application of mimetic theory to a range of disciplines, especially the social sciences. Articles could give an overview of work that has been done in a field or present original research, or a mixture of both, and would need to be readable by non-specialists. If you might be interested in contributing, please email me.

Forthcoming Events

2018 Annual Meeting

COV&R’s next annual meeting will be held at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, 11-14 July 2018, and organized by Stephen McKenna, who chairs CUA’s Department of Media and Communication Studies.

COV&R’s next annual meeting will be held at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, 11-14 July 2018, and organized by Stephen McKenna, who chairs CUA’s Department of Media and Communication Studies.

The conference theme, “Politics, Religion & Violence: After Truth” suggests our supposedly “post-factual” cultural moment. Yet it also indicates ‘the pursuit of truth,” and it asks us to think about where we are and who(se) we become both when truth is obscured and after it is disclosed. Truth, deception, and indifference to truth are foundational concerns of mimetic theory, and the moment is apt to revisit them. The 2018 conference invites scholars and practitioners to share research related to this theme, engaging with mimetic theory across the disciplines.

Possible topics within the theme include:

- How can mimetic theory cast light on the purportedly “post-truth” conditions of contemporary political discourse?

- How do works of art disclose truth, its counterfeits, and their (mis-)appropriation(s)?

- How do discourses blind their participants to the truth of mimetic desire and conflict?

- Ideological left and right as mimetic doubles

- Egalitarian society and history as mimetic objects

- The “Clash of Civilizations” and religious simulacra

- Mimesis and social media in the “post-truth” moment

- Mimetic theory and satire

- Mimetic theory and controversy over historical memorials

- Mimetic perspectives on the Vietnam War and Truth (50 years after the Tet Offensive)

The call for papers will be announced this fall on the COV&R website.

Philosopher Paul Dumouchel, author of The Ambivalence of Scarcity and The Barren Sacrifice, has been confirmed as a plenary speaker. The program hopes to feature book sessions on:

- Goodhart, Möbian Nights: Reading Literature & Darkness

- Bubbio, Intellectual Sacrifice & Other Mimetic Paradoxes

- Palaver/Schenk, Mimetic Theory & World Religions

- Humbert, Violence in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock

Other program possibilities include a panel on sacred space and the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception (located at CUA), an excursion to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the soon-to-open Museum of the Bible, and/or sites on the National Mall.

Catholic University of America, the national university of the American Roman Catholic bishops, is a large, quiet, urban campus conveniently located on the DC Metrorail with easy transit to off-campus hotels, air and rail hubs, and the wider city. It offers affordable campus lodging ($~60 per night) with good on-campus and local dining options. Its lively Brookland neighborhood (“Little Rome”) features pubs, restaurants, shops, bookstores, and an Arts Walk.

Workshop and Theatre Event

Celebrating the Raven Foundation’s 10th Anniversary

Saturday, October 21

Free Workshop – Crown Center Lobby, Loyola University Chicago Lake Shore Campus, 1-5 p.m.

Hard Times for Truth

In these hard times for truth, Raven Board member Andrew McKenna and Raven Award Winner Heidi Stillman examine Charles Dickens’ novel, Hard Times, and the crisis of difference between truth, facts, and lies.

Refreshment break

Hot Times for Scandal

When truth falls on hard times, scandal finds fertile ground. Vanessa Avery and Stephen McKenna apply the mimetic insight about desire, rivalry and violent doubles to escalating conflicts in the workplace, politics, and the media.

Wine and cheese reception at 5:00pm

Sunday, October 22, 2:00 p.m.

Hard Times at Lookinglass Theatre, adapted and directed by Heidi Stillman

Join Raven Foundation staff, board members and Raven Award winners for this matinee performance of Hard Times, Heidi Stillman’s award-winning, circus-infused adaptation of the Charles Dickens novel. Following the performance, Heidi and Andrew McKenna will lead a post-show discussion with the audience.

Tickets will be available for purchase soon from the Lookingglass Theatre box office. Lookingglass Theatre is located at 821 N. Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois. Directions, parking and dining information are available.

RSVP and Ticket Information

The Saturday workshop is free, including the refreshment break and reception following the workshop. An RSVP is greatly appreciated. Please reply via email. Directions and parking information for the Loyola Lake Shore campus are just a click away.

Tickets for the Sunday matinee performance of Hard Times can be purchased from the Lookingglass Theatre box office. Lookingglass Theatre is located at 821 N. Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois. Directions, parking and dining information are available.

COV&R Sessions at the American Academy of Religion Annual Meeting

Boston, November 18–21, 2017

Grant Kaplan, Coordinator

Saint Louis University

This Fall’s offerings at the AAR are not as lush as last year’s. Still, they offer an exciting opportunity. The first panel consists in the overflow proposals from the 2016 meeting. The second panel, while not technically a book panel, will revolve about the forthcoming book edited by Joel Hodge and Scott Cowdell, and it includes an impressive array of respondents.

Session I (P 18-113): Saturday 9:00am–11:30am

Westin Copley Place – Defender (Seventh Level)

(Please note that the business meeting follows immediately at 11:30am.)

Theme: “Girard’s Legacy: Continuing the Conversation”

Convener: Grant Kaplan

Moderator: Brian Robinette, Boston College

Panelists:

- Stewart Clem (University of Notre Dame), “Nonviolent Grammar of Sacrifice”

- Anthony Bartlett (Syracuse, New York), “Between Girard and Heidegger: A New Ontology”

- Chris Haw (University of Notre Dame), “Girard at Intersection of Analogy and Dialectic”

Session II (P19-111): 9:00AM–11:30AM

Hilton Back Bay – Adams (Third Level)

Theme: “Book Review: Does Religion Cause Violence? Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Violence and Religion in the Modern World”

Convener: Grant Kaplan

Moderator: Jeremiah Alberg, International Christian University, Japan

Panelists:

- Scott Cowdell (Charles Sturt University, Australia) and Joel Hodge (Australian Catholic University), “Introduction to the Volume, Does Religion Cause Violence (Bloomsbury, 2017)”

- William Cavanaugh, (Depaul University), “Girard and the Myth of Religious Violence”

- Joel Hodge, “Why is God Part of Human Violence? The Idolatrous Nature of Modern Religious Extremism”

- Wolfgang Palaver (University of Innsbruck, Austria), “Religious Extremism, Terrorism, and Islam: A Mimetic Perspective”

- Asma Afsaruddin (Indiana University) “Islam and Violence: Debunking the Myths”

- James Jones (Rutgers University), “Review of the Volume: Does Religion Cause Violence?”

Conference Reports

Report on COV&R’s 2017 Annual Meeting

by Curtis Gruenler

This year’s COV&R meeting in Madrid once again brought home the remarkable breadth of mimetic theory—its applicability across time periods and academic disciplines, its fruitfulness for both theoretical analysis and lived practice. I am always especially glad to meet those who work more on the practice than the scholarship side. Prominent this year, all the more so after last year’s first-ever meeting in the southern hemisphere, was COV&R’s geographical scope. All of this range was most apparent in the wealth of concurrent sessions, but this report will confine itself to the plenaries.

The session featuring João Cezar de Castro Rocha of Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro and Carlos Mendoza-Álvarez, OP, of Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City highlighted for me what mimetic theory gains as it is taken up by scholars around the world and how urgent and promising it is to connect theory to practice. Castro Rocha, whose book ¿Culturas shakespearianas?: Teoría mimética y América Latina is being translated into English for MSU Press, introduced the idea that Shakespearean cultures experience the force of desire on a collective interdividual level. Latin American authors have explored how the situation of a culture that recognizes itself through the eyes of others extends and complicates interdividuality, Girard’s only neologism. Shakespeare proves to be a guide to moving from the anxiety of influence to a “poetics of emulation” and thus turning the problem of cultural secondarity into a strength.

The reception of mimetic theory in Latin America, noted Mendoza-Álvarez, has long focused on its social pertinence (a point also made by Castro Rocha in his 2014 article in Contagion). Mendoza-Álvarez proposed that the idea of collective interdividuality can give insight into the collective experience of rivalry and victimage involved in systemic violence and also opens possibilities for envisioning collective reconciliation. The Latin American path of facing violence through “memory, justice, and reconstitution of communal tissue” can gain from the encounter between mimetic theory and the epistemologies of the global South. Mendoza-Álvarez focused this challenge to “decolonize mimetic theory” on several points of debate and, I take it, potential resonance: “a sense of belonging to the earth”; “communal perspective…beyond the West’s individualist vision”; “sapiential knowledge”; and “the spiritual sense of existence” marked by such things as the communal feast.

Two sessions brought the connection between theory and practice into a European context. The presentations by Jon Juaristi (Universidad de Alcalá de Henares) and Florentino Portero (Universidad Francisco de Vitoria) explored the relationship between regionalism and nationalism in Spain. Portero described the emergence of “political religions” while Juaristi showed how reception of Girard’s work played a part in Basque resistance beginning in the 1960s.

Taking a broader European perspective, Roland Hsu of Stanford University pointed out the paradoxical rise of nationalist movements seeking pan-European unity against Europe. Hsu’s analysis of political and economic trends shaping the future of Europe emphasized the continuing challenges of immigration that are turning its attention from east to south and making EU-Africa summits more important. Duncan Morrow of Ulster University, drawing on his experience as a member of the Corymeela Community, argued that political treaties can only point to what is really needed: desisting from mimetic rivalry. “The biggest problem,” he said, “is that we no longer know who we are after reconciliation.” The attraction of antagonistic identity remains. “Reconciliation is not rational peace-building,” Morrow concluded, “but a change in relationship. The only answer is a good model.”

Taking a broader European perspective, Roland Hsu of Stanford University pointed out the paradoxical rise of nationalist movements seeking pan-European unity against Europe. Hsu’s analysis of political and economic trends shaping the future of Europe emphasized the continuing challenges of immigration that are turning its attention from east to south and making EU-Africa summits more important. Duncan Morrow of Ulster University, drawing on his experience as a member of the Corymeela Community, argued that political treaties can only point to what is really needed: desisting from mimetic rivalry. “The biggest problem,” he said, “is that we no longer know who we are after reconciliation.” The attraction of antagonistic identity remains. “Reconciliation is not rational peace-building,” Morrow concluded, “but a change in relationship. The only answer is a good model.”

Cesario Bandera (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), building on themes from his most recent book, A Refuge of Lies (reviewed in Bulletin 44 [May 2014], pp. 8-11), engaged with fundamental Girardian anthropology in a way that also raises implications for practice. Questioning whether it is possible for mimetic theory to explain the emergence of humanity on a purely scientific, natural basis, Bandera posited that a sense of non-violent transcendence must precede scapegoating if the murderous crowd is to sacralize its own violence. This prior knowledge of the divine then manifests as the persecutors’ knowledge of their guilt. If, in the modern world, we have become aware that we are headed for catastrophe, there is some hope in knowing we are the cause, but knowledge is not enough. “The problem,” he said, “is that we will never be scared enough.” Freedom to repent comes from participating in divine love that surrenders power.

Neuropsychiatrist Jean-Michel Ourghoulian, long-time collaborator with Girard, similarly affirmed a desire to create that is the image of God in humanity, as portrayed in Genesis 1, and precedes the mimetic desire that becomes rivalry with the serpent and Eve in Genesis 3. His explication of the problems of alterity and responsibility—the locating of psychic disease in causes both internal and external—from Plato, Cicero, and Galen to Augustine and Freud, concluded that mimetic desire is the epitome of unconsciousness, recognition of which requires a process that is not just emotional or cognitive but initiatory. A clue to how this process could play out, not just individually but collectively, might be found in James Alison’s comment after the talks by Castro Rocha and Mendoza-Álvarez, that secondariness, with humility, is a precondition for creativity.

Neuropsychiatrist Jean-Michel Ourghoulian, long-time collaborator with Girard, similarly affirmed a desire to create that is the image of God in humanity, as portrayed in Genesis 1, and precedes the mimetic desire that becomes rivalry with the serpent and Eve in Genesis 3. His explication of the problems of alterity and responsibility—the locating of psychic disease in causes both internal and external—from Plato, Cicero, and Galen to Augustine and Freud, concluded that mimetic desire is the epitome of unconsciousness, recognition of which requires a process that is not just emotional or cognitive but initiatory. A clue to how this process could play out, not just individually but collectively, might be found in James Alison’s comment after the talks by Castro Rocha and Mendoza-Álvarez, that secondariness, with humility, is a precondition for creativity.

Several avenues of conversation between mimetic and other theories emerged from the presentation by neuroscientist Beatriz Calvo-Merino (University of London) of her discovery of differences in “internal resonance” between the brains of those who observe complex movements, such as ballet dancing, depending on whether they have practiced such movements themselves. This work, framed by Daniel Wolpert’s argument that the basic purpose of brains is to produce complex movement (available as a TED talk), also builds on the discovery of mirror neurons. What, she asked, is the function of such internal resonance? Possibilities such as imitation, social learning, action understanding, and emotion recognition might all conceivably have to do with mimetic desire and suggest directions for further experiment as well as interchange with neuropsychologists about how to interpret the results. (Side note: Internal resonance might also help explain why watching football, i.e. what we Americans call soccer, is so much more enjoyable for those who have played it, whereas everyone has practiced the basic actions of American football and baseball: running, throwing, catching, and hitting.)

Wolfgang Palaver (Universität Innsbruck) connected theory to practice by, as he so often does, putting mimetic theory in dialogue with another established body of thought, in this case Terror Management Theory. Built on the work of Ernest Becker, with whose followers COV&R had interactions as long ago as 1995 (see James Williams, Girardians, p. 96), Terror Management Theory includes a model of the escalation and de-escalation of intergroup conflict that bears striking resemblance to a mimetic understanding of violence and in which positive, non-violent mimesis can be seen as an important de-escalating factor.

Sandor Goodhart asked what interfaith dialogue might look like in a time of disasters, such as the Holocaust, when death has become “a premise and not a future.” He explores this situation more broadly in his new book, Möbian Nights: Reading Literature and Darkness. “We can be sure that it would not rely upon a trust in the effectiveness of dialogue alone, or in the triumph of the human spirit of cooperation and rational communication in the face of insuperable adversity.” It would depend rather, he suggested, “upon the acceptance in individual cases of the infinite responsibilities for the other individual as someone like Emmanuel Levinas describes them and as René Girard would undoubtedly endorse them.”

Sandor Goodhart asked what interfaith dialogue might look like in a time of disasters, such as the Holocaust, when death has become “a premise and not a future.” He explores this situation more broadly in his new book, Möbian Nights: Reading Literature and Darkness. “We can be sure that it would not rely upon a trust in the effectiveness of dialogue alone, or in the triumph of the human spirit of cooperation and rational communication in the face of insuperable adversity.” It would depend rather, he suggested, “upon the acceptance in individual cases of the infinite responsibilities for the other individual as someone like Emmanuel Levinas describes them and as René Girard would undoubtedly endorse them.”

Lyle Enright’s essay “Girard, Agamben, and the Glory of the Lord,” winner of this year’s Raymond Schwager Memorial Prize, laid down lines of fruitful exchange between the work of these two thinkers. Both theorize social unity through ritualized exclusion—Agamben in his famous notion of the homo sacer, an ancient Roman term for one who is not fit to be sacrificed but can be killed with impunity and serves the formation of sovereign power. Yet Agamben keeps religion marginal as merely preparatory to philosophy and politics. Enright explored the consequences that follow from the different roles played by the sacred as seen by each.

Palaver’s interview with Pankaj Mishra provided a fittingly wide-ranging conclusion to our meeting. Mishra, a frequent contributor to such publications as The Guardian, The New York Times (also a new piece on his native country, India), and The New Yorker, has been engaging with mimetic theory at least since he was invited by New Perspectives Quarterly to respond to an interview with Girard in 2005. His most recent book, The Age of Anger, gives a rich and illuminating account of the roots of contemporary, global violence going back to Rousseau, one in which mimetic desire, rivalry, and ressentiment are central explanatory concepts. Picking up on themes from the book, Mishra asserted the importance of mimesis, rather than old texts, in understanding jihadist and other violence and suggested that the rise of “gods of the economy” is a kind of Enlightenment fundamentalism that, just as much as religious fundamentalism, indicates the decline of traditional religion.

Palaver’s interview with Pankaj Mishra provided a fittingly wide-ranging conclusion to our meeting. Mishra, a frequent contributor to such publications as The Guardian, The New York Times (also a new piece on his native country, India), and The New Yorker, has been engaging with mimetic theory at least since he was invited by New Perspectives Quarterly to respond to an interview with Girard in 2005. His most recent book, The Age of Anger, gives a rich and illuminating account of the roots of contemporary, global violence going back to Rousseau, one in which mimetic desire, rivalry, and ressentiment are central explanatory concepts. Picking up on themes from the book, Mishra asserted the importance of mimesis, rather than old texts, in understanding jihadist and other violence and suggested that the rise of “gods of the economy” is a kind of Enlightenment fundamentalism that, just as much as religious fundamentalism, indicates the decline of traditional religion.

Let me add my thanks to Ángel Barahona and the other organizers, panel moderators, speakers, and everyone at the Universidad de Francisco Vitoria who contributed to an invigorating and convivial meeting.

Additional photos of the Annual Meeting taken by Matthew Packer are available here.

Report on the 2017 Theology & Peace Conference: Embracing We-Centricity

by Susan Wright

President, Theology & Peace

“I’m not okay. When you ask me in passing how I am, I may answer ‘fine’… We all answer with the same line, ‘I’m fine. How are you?’ But none of us are okay. On 9/11, the American people experienced a massive trauma. We are suffering from a form of collective PTSD we have yet to address. We are not okay.”

“I’m not okay. When you ask me in passing how I am, I may answer ‘fine’… We all answer with the same line, ‘I’m fine. How are you?’ But none of us are okay. On 9/11, the American people experienced a massive trauma. We are suffering from a form of collective PTSD we have yet to address. We are not okay.”

~ Sereta Richardson

Last May, Theology & Peace held our tenth anniversary conference: “Embracing We-Centricity: Practices that Nurture the Common Good.” Our theme was inspired in part by Vittorio Gallese’s use of the term “we-centricity” to describe our inherent openness to the other:

“Every time we relate to other people, we automatically inhabit a we-centric space, within which we exploit a series of implicit certainties about the other. This implicit and pre-theoretical, but at the same time contentful state enables us to directly understand what the other person is doing, why he or she is doing it, and how he or she feels about a specific situation.” (“The Two Sides of Mimesis,” Mimesis and Science, 100)

While mimetic theory helps explain our interconnectedness, it more importantly reveals why “we-centricity” is also problematic, why the “common good” has historically been a bad thing for those who have been victimized and excluded. Beginning with our 2013 conference, “Lynching, Scapegoating & Actual Innocence,” Theology & Peace has examined the history of racism, the inherited trauma of slavery and lynching, and the continued destruction to black communities unleashed by the War on Drugs. With the mass incarceration of black men, the American people are engaging in scapegoating on a horrific scale. As pastors, theologians and activists, our goal is to educate our faith communities on the sacrificial foundations which structure our corporate life. And going beyond diagnosis, we seek practical models for nonviolent action that subvert the deep structures of racism, that interrupt the negative rhetoric directed against immigrants, Muslims, and LGBTQ persons, and that de-escalate mimetic contagion before it sweeps us up in its wake.

A year ago, at this time, the board of Theology & Peace recognized that whatever the results of the U.S. presidential election, the American people would be deeply divided. Sick with rivalry and self-righteous contempt on all sides, our public discourse has been reduced to a circus of model-obstacle relationships. The language of universal rights is stifled by a growing rhetoric of hate and resentment. We do not have to accept this as the new normal. René Girard bequeathed us the tools not only to parse the mimetic dynamics fueling the rise of populism and “the age of anger,” but to set the stage for a new era of political and social engagement.

At this year’s Theology & Peace conference, we engaged spiritual practices which, repeated over time, can transform our habitual ways of being together. Drawing on a variety of faith traditions, our speakers provided us with tangible tools not only for building our resistance to the unconscious dynamics responsible for scapegoating, but for creating compassionate spaces for healing our individual and collective trauma.

Sister Rose Pacatte led us in “Watching Film as a Spiritual Practice,” an adaptation of lectio divina, the ancient monastic practice of receptivity to the power of scripture. Together we watched the film The Visitor about a man who arrives home to discover illegal immigrants camped out in his NYC apartment. Sr. Rose asked that we identify with a character in the film—that we reflect on a scene in movie which seemed to “choose us” and share with others the ways the film touched our hearts. Our ego-centric engagement with the film was suspended just enough that we found ourselves impacted in unexpected ways.

Sister Rose Pacatte led us in “Watching Film as a Spiritual Practice,” an adaptation of lectio divina, the ancient monastic practice of receptivity to the power of scripture. Together we watched the film The Visitor about a man who arrives home to discover illegal immigrants camped out in his NYC apartment. Sr. Rose asked that we identify with a character in the film—that we reflect on a scene in movie which seemed to “choose us” and share with others the ways the film touched our hearts. Our ego-centric engagement with the film was suspended just enough that we found ourselves impacted in unexpected ways.

Theology & Peace board member Sereta Richardson presented on Circle Processes. A black woman, a single mother, a veteran, and a former police officer, Sereta recounted with unusual eloquence and honesty the pain of a life marked by trauma and PTSD. She described the release that comes with sharing with others around the circle the suffering that each of us has bottled up inside. Delivering the words quoted above, she warned us. As long as 9/11 and its unprocessed pain remains bottled up in the American people, our collective PTSD poses a threat to ourselves and to the rest of the world, too often seeking release by targeting others in our midst. Inviting us to join her in a circle process, Sereta asked that those who were willing vocalize what they’re most afraid of. As we went around the room, we could feel our shared space shift from fear to compassion.

Theology & Peace board member Sereta Richardson presented on Circle Processes. A black woman, a single mother, a veteran, and a former police officer, Sereta recounted with unusual eloquence and honesty the pain of a life marked by trauma and PTSD. She described the release that comes with sharing with others around the circle the suffering that each of us has bottled up inside. Delivering the words quoted above, she warned us. As long as 9/11 and its unprocessed pain remains bottled up in the American people, our collective PTSD poses a threat to ourselves and to the rest of the world, too often seeking release by targeting others in our midst. Inviting us to join her in a circle process, Sereta asked that those who were willing vocalize what they’re most afraid of. As we went around the room, we could feel our shared space shift from fear to compassion.

Boston College theologian Brian D. Robinette shared his work integrating mimetic theory with Christian contemplative practice. Distilling the wisdom of the desert monastics and contemporary teachers like Belden Lane and Martin Laird, Brian described multiple ways contemplative practice loosens mimetic binds, freeing us from rivalry with our neighbors in order that we may truly love them. Turning the gaze inward, we come to recognize the many borrowed desires within us! In the “practice of stillness,” we don’t judge those desires or afflicted emotions, we just take notice, “this is what envy feels like,” and without commentary we simply let them go. Stepping back from the many mimetic hooks we encounter on a daily basis, we quietly observe their passage down the stream of conscious awareness. Over time, the contemplative learns “to become creatively ‘indifferent’ (or ‘non-reactive’) to the riot of mimetic comparisons”. Brian offered us this image: “we can become dispassionate witness to the thoughts and desires streaming though us, as though watching particles swirling in a snow globe.” (See his article, “Contemplative Practice and the Therapy of Mimetic Desire,” Contagion 24 [2017], pp. 73-100, quotations from pp. 87 and 89.)

Jonathan Brenneman, Coordinator for Israel/Palestine Partners in Peacemaking, Mennonite Church USA, presented on “The Spiritual Practice of Nonviolent Direct Action.” A member of Christian Peacemaking Teams (CPT), he stood with victims of aggression in Hebron (Palestine), at Standing Rock, and in South Africa. Jonathan shared faith-based strategies focused on de-escalating conflict and improving conditions for victims of oppression and violence. Following the poet Joy Harjo, Jonathan emphasized that we treat the enemy as worthy of engagement. Do not demonize the oppressors, but view them as mistaken. Include them in solutions understood as correction rather than victory. Jonathan described a critical moment in Hebron when the checkpoints closed suddenly, making it difficult for Palestinian school children to return home. CPT utilized their training to engage the soldiers as part of the solution rather than treating them as enemies worthy only of hate. Jonathan concluded by engaging us in role play between the victim, the aggressor, and active bystanders able to disrupt the status quo. He equipped us with an extensive list of best practices: “feel the discomfort, assess what’s happening, be aware of how many people are around, be aware of exists.…” (The entire list is on our website.) The final word: “Remember that the aggressor is loved by God and wants to act positively.” Jonathan quoted Thomas Merton: “The tactic of nonviolence is a tactic of love that seeks the salvation and redemption of the opponent, not his castigation, humiliation, and defeat” (Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander [Image, 1968] 86).

Elder CW Harris, founder of Intersection of Change (formerly Newborn Holistic Ministries), led an ecumenical worship service honoring his mentor, Gordon Cosby, founder of Church of the Savior in Washington, DC. His sermon described how he, a young black man, was “seized by a great affection.” Cosby introduced him not only to mimetic theory, but to a communal faith life shared with the victim—the homeless, junkies, ex-convicts. Cosby’s witness helped CW rise above anger and resentment, the collective response of many young blacks to the crushing reality of racism. Today CW continues to share that communal life in his community, Sandtown, Baltimore, a neighborhood ravaged by race riots in the ’60s and more recently by the War on the Drugs. Since the death of Freddie Gray, Sandtown has been at the center of the conflict between police and people of color. In the midst of the crisis, CW, building on the positive models he received from Gordon Cosby, has worked tirelessly to de-escalate the violence.

Elder CW Harris, founder of Intersection of Change (formerly Newborn Holistic Ministries), led an ecumenical worship service honoring his mentor, Gordon Cosby, founder of Church of the Savior in Washington, DC. His sermon described how he, a young black man, was “seized by a great affection.” Cosby introduced him not only to mimetic theory, but to a communal faith life shared with the victim—the homeless, junkies, ex-convicts. Cosby’s witness helped CW rise above anger and resentment, the collective response of many young blacks to the crushing reality of racism. Today CW continues to share that communal life in his community, Sandtown, Baltimore, a neighborhood ravaged by race riots in the ’60s and more recently by the War on the Drugs. Since the death of Freddie Gray, Sandtown has been at the center of the conflict between police and people of color. In the midst of the crisis, CW, building on the positive models he received from Gordon Cosby, has worked tirelessly to de-escalate the violence.

With recent events in Charlottesville, these are practices and models we sorely need.

Where do go from here? In our final conference session all those in attendance agreed we would create an online resource for those interested in cultivating the spiritual practices presented at the conference. We also invite you to join our Facebook page and participate on our Facebook discussion page. Please go to our website and consider becoming a member and/or making a donation.

Join us next year: 2018 Theology & Peace Conference “(Un)othering: Recognizing Ourselves in Each Other,” May 21-24 in Nashville, Tennessee. Speakers include Becca Stevens, founder of Thistle Farms.

Report on the Andean Girard Summer School

Colombia, June 2017

by Jorge Carrasquel Petit

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogata

We arrived at midday on Saturday June 10th. The sky was clear blue and the paving stones bright and hot. We were surrounded by hills carpeted in green, as usual in the Cundinamarca landscape: we had come to the Salesian retreat house in Fusgasugá, Colombia. Our purpose: to spend six days delving into the work of René Girard, searching for meaning and the understanding of our everyday lives. We were: Andean priests, social scientists, social activists, literary critics, classicists and philosophers. We came from Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela, and of course from Colombia.

We were enthusiastic, young, and not so young.

Iván Camilo Vargas was key to making our gathering possible: he was in charge, and good at it, since everything logistical happened just right. Also key was Roberto Solarte since it was from him that the invitations had arrived. Many thanks to Imitatio for its financial support.

Our “summer school” began with a long lecture, punctuated with discussion, by Roberto Solarte. He presented the arguments and themes to be found in Deceit, Desire and the Novel. These were presented along with fragments of the book, which we analyzed and hashed out. As we did so, some issues were recurrent. One was the never-ending Latin American question about our identity, on which Girard’s book offered to shed new light, as João Cesar Castro de Rocha has demonstrated. Ethics was another major concern. Over and over again we asked what to do with our desire if novelistic conversion goes beyond our will and requires an act of the Holy Spirit. For sure, the seminar enabled us all to begin understanding our motivations, and those of others, in a new way.

Now full of questions, we arrived at Stéphane Vinolo’s presentation of Violence and the Sacred. His great performance took us below the cultural surface and showed us how mimetic violence and sacrifice came to be the cornerstone of our beliefs, norms, and mythical systems. To this end he made an epistemological distinction between what he called the micro and the macro perspective. With that in mind we went through feasts and carnivals, language, religions, pyramids, as well as several customs and political systems, always using Girard’s method of reading and interpreting myths, rituals and Greek tragedies. At the end we received a very subtle-seeming picture of history. As with Roberto’s sessions, we wondered what to do now: this time with the institutions we live in rather than with our personal lives. Once méconnaissance is no longer present, many things threaten to break loose.

Finally we came to Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. James Alison concentrated on Section II: The Judeo-Christian Scriptures, possibly the most polemical and least expected development within Girard’s theory of everything. With erudition and theatrical skills James showed how similar, and yet how distinct biblical stories are in the face of other rituals, myths, and tragedies. First he synthesized the common, sacrificial reading of Jesus’ Passion. Next he compared the story of Cain and Abel with other myths, moving then to the account of Solomon’s judgment of the two prostitutes. Third, we read and analyzed the narrative of Jacob and Joseph, and that of Abraham and Isaac, once again finding clues that deconstruct sacrifice and rituals. Finally we turned to some texts from the Gospels, guided by James pointing out how Jesus had to use the language, manners, and rituals of the sacrificial order in order for his message to be comprehensible. If expressed plainly and at once, no one could grasp it. As we read The Parable of the Prodigal Son, Jesus’ message shone with a distinctively new light: all are guilty, all are victims, all have thrown stones. Though we are all rivals, heaven is possible in forgiveness and reconciliation with each other.

It wasn’t only the presentations and readings that were highly stimulating; so also were the discussions and comments from the participants. Some of us, wanting to take advantage of the wisdom of our peers, presented ideas and outlines from our research projects. For example, one of us is working on developing a process of conversion to promote peace and reconciliation through the practice of aikido. Another shared with us his analysis of the sacrificial aspect of art history, especially in modernity, where the artist may become a sort of scapegoat, simultaneously feared and revered. A third had come to a deeper understanding of Dostoyevsky through Girard’s reading, especially of the Grand Inquisitor passage. This was helping him develop his own interpretation of the reception of early modernity in Russian thinkers.

Suddenly it was mid-day, June 16th, and we were leaving Fusagasugá, with the firm hope of keeping in touch, collaborating, and giving each other support. Everyone was happy, full of expectation, and of uncertainty at things that are to come.

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the book review editor, Matthew Packer.

Ways of Mimesis and Atonement

Review by Robert J. Daly, S.J.

Boston College

Michael Kirwan and Sheelah Treflé Hidden, eds., Mimesis and Atonement: René Girard and the Doctrine of Salvation. Violence, Desire, and the Sacred 5. Bloomsbury, 2017. Pages xv + 185.

Michael Kirwan and Sheelah Treflé Hidden, eds., Mimesis and Atonement: René Girard and the Doctrine of Salvation. Violence, Desire, and the Sacred 5. Bloomsbury, 2017. Pages xv + 185.

This is a uniquely important book, despite it being, or perhaps, in this case, precisely because it is, a collection of chapters by nine different authors. For it not only lives up to the opening claim of its editors: “The chapters of this book are intended to update and consolidate existing debates within Mimetic Theory (MT) and theology, and also to break new ground” (xii). It also does justice to the plea and promise of Rowan Williams in the foreword: “We are in need of careful and imaginative readings of our tradition in the light of Girard’s remarkably fertile models—and this is what the present collection splendidly does for us. . . . not just a book about one topic but an invitation to think about the method of a whole discipline. It is a book that should help theology to be more itself” (xv).

In Chapter 1: “Traversing Hostility: The sine qua non of Any Christian Talk about Atonement” (1–15), James Alison begins with a typically delightful/insightful Alisonian “exegesis” of Matthew’s version of the Parable of the Wicked Tenants/Murderous Vinedressers under the (in critical terms) politically incorrect subheading, “Recovering Our Lord’s account of his atonement.” Alison insists that this is a parable about and not against the Scribes and Chief Priests—and, by implication, about us as well—inviting them/us to move beyond their/our retribution logic of righteous innocence, and thus become open to forgiveness. Forgiveness, Jesus seems to be saying, is prior to being.

In Chapter 2, “Jewish Atonement and the Book of Jonah” (17–32), Vanessa J. Avery pursues the implications of the fact that the Book of Jonah is a featured reading towards the end of the lengthy modern Jewish liturgy of Yom Kippur. Something in that book helps the community to an attitude of at-one-ment. Avery highlights the remarkably nonviolent behavior of the sailors towards the God-fleeing Jonah as an example of how not to get caught up in a crisis, and of how not to fall unconsciously into violent scapegoating (20). But in the end, they succumb (by “contagion”?) to Jonah’s sacrificial mind-set by throwing him overboard, and then by blaming God for this crime and offering sacrifice. Equally remarkable, then, is the conversion of the Ninevites. In that event there is no mention of force, power, violence, or the traditional actions of sacrificial atonement that one might expect. In one brief paragraph, Avery alludes to the significance of all this and, in the context of mimetic theory, the genius of the Jewish tradition in confronting its people, in the final hours of its most solemn liturgy, with this extraordinary Jonah story. “In the sailors and the Ninevites, then, we have two very different kinds of atonement. Each kind of atonement is effective: the sailors do manage to stop the storm; the Ninevites are delivered. But the former is done through exclusionary human violence, generates a deity that requires violence, and in turn ritualizes violence; while the latter is done through a complete renunciation of violence in both intention and action” (27).

In Chapter 3, “Orthodox Debates in the Twentieth Century on the Question of Atonement” (33–46), Antoine Arjakovsky hails the Paris School of Nicolas Berdyaev and Serge Boulgkov, and urges us, in the context of the current Russian-Ukrainian conflict, to “recall the renewal that took place within the Paris School in the Russian Orthodox emigration of the years 1920–30” (33). Although these émigrés often disagreed among themselves, they tended to agree with the view, as Boulgkov put it, that “God created the world to be incarnated. He created it because of this incarnation. This is not only a means of redemption, but it is his ultimate coronation. Embodying himself God showed his love for creation” (35). Groping for a more theologically defensible theodicy, these émigrés basically followed the late second-century Irenaeus of Lyon in insisting that, in effect, “Christ must not be understood as a scapegoat” (36). Arjakovsky then explains how the personalism of Berdyaev could contribute toward a soteriological deepening that helped him to clarify that “God became incarnate so that humanity might be divinized. In this perspective, the coming of the God-man should be seen dynamically, as the accomplishment of the project of creation, and only secondarily as the salvation of mankind” (39).

In Chapter 4, “Wright, Wrong and Wrath: Apocalypse in Paul and in Girard” (47–70), Stephen Finamore outlines the bewildering scene of recent Pauline scholarship: (1) the demolition of traditional Protestant frameworks by the “New Perspective” on Paul movement popularized by N. T. Wright; (2) “the continuing liberal attempts to blame Paul for all the ills of both the church and the modern world”; (3) ongoing Catholic attempts “to liberate Paul from his Babylonian captivity within Protestant exegesis”; and now (4) “René Girard with the Girardians in his wake.” In seeming desperation at this complexity, Finamore begins his search for clarity by focusing on the issue of the wrath of God, mostly in Romans 1, but also in 2 Thessalonians, Ephesians, and Colossians. Finamore suggests that Wright somewhat exaggerates the claim that Paul sees the wrath of God as primarily apocalyptic and eschatological, but that he is correct in seeing it as having a trans-historical dimension. Somewhat in contrast, Girard insists, especially in his later years, that the “apocalyptic moment,” the moment of “sacrificial crisis,” is not in our future but in our past. It is already part of human history (66–68).

With Anthony Bartlett, in Chapter 5, “Paul and Girard Agonistes: Against Theological Violence” (71–94), we approach the theological heart of this extraordinary book, an all-too-rare attempt to answer “the question of theological violence—the use of generatively violent images and themes to construct theological meaning” (72). Bartlett, following Girard, “sees the revelation of the victim as a kind of knowledge [emphasis mine] setting us free” (84). For, “once it is asserted that the death and resurrection of the Messiah is not some kind of legal transaction, but, rather, the apocalyptic disclosure of an entirely new form of humanity, then the anthropological revelation of knowledge flows naturally and necessarily” (85). Pushing the envelope this way becomes what Bartlett describes as looking like “a slow painful retreat from knowledge [instead of religious revelation] as a transformative power in human history” (88).

Nikolaus Wandinger in Chapter 6, “Salvation through Forgiveness or through the Cross? Raymund Schwager’s Dramatic Solution to a False Alternative” (95–114), continues this pushing of a specifically theological envelope by asking the question: Does God grant forgiveness unconditionally—or, does God grant forgiveness only because, in a sense, God is forced to by Jesus’ death? Wandinger reports (and develops!) how Schwager’s dramatic theology of atonement could resist this as a false alternative; for it is not a question of salvation either through the cross or through the message of the kingdom; one can actually affirm a both/and solution. Wandinger’s subsection: “The meaning of the term” (105–111)—in this case “atonement”—is a brilliant example of how theological argument, especially by refusing to be limited or controlled by preconceived ideas, can escape crippling false alternatives.

Michael Kirwan’s Chapter 7 survey of MT and the doctrine of atonement, “‘Strategies of Grace’: Mimesis as Conversion in Girard and in Theology” (115–134) begins with an account of the distinct but convergent trajectories of René Girard and Raymund Schwager. This is, Kirwan notes, difficult to summarize, for it is an incomplete conversation, both because of the premature death of Schwager and because of the massive development in Girard’s thought both during the time of the conversation (1974–1991) and the time since then. One of the goals of that conversation, towards which many Girardians are still working, was to attain a theologically adequate doctrine of atonement that is supported by the metaphors or pictures that instantiate it, and which also remains faithful both to the biblical narrative and to the “scientific” need to be universalizable (127). For “it is a working scientific hypothesis, not simply a useful fiction” (129). Kirwan then, citing Mulhall, points out that three notable modern philosophers, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Wittgenstein, all have “something of an analogue to the theological doctrine of ‘the Fall,’” but all three refuse to accept that the redemption needed is “attainable only from a transcendental or divine source” (130).

In the penultimate Chapter 8, Duncan Morrow’s “Violence Unveiled: Understanding Christianity and Politics in Northern Ireland after René Girard’s Rereading of Atonement” (135–151) details the revelatory power of mimetic theory when brought face-to-face with the recent history of Northern Ireland. That situation is a classic illustration of mimetic theory, but with a unique twist: outside forces prevented the normal mechanisms of mimetic theory from running their normal course. As a result, for decades, “Violence was not stopped but managed. Conflict was not resolved but channeled and dammed. Killing continued, but at a level that did not consume the system” (147). This situation of mimetic mechanisms in quasi-suspended animation gradually allowed the opposing parties to see themselves as removed from the company of the good, “and to reconfigure ourselves not as innocent, but as complicit and forgiven, and to see in the crucifixion and resurrection narrative of the gospel the way, the truth and the life in an entirely practical sense” (150).

Chapter 9, “Sacrifice and Atonement: Strengthening the Trinitarian Aspects of Mimetic Theory” (153–181) by Arpad Szakolczai brings this remarkable book to a remarkable close. Observing that Girard’s theory actually offers “a social-scientific justification of the gospels” (154), he further notes the importance of Girard’s attempt “to take literally and historically the story told by the gospels” (154). But his overriding purpose, moving beyond Girard, “is to show that the sacrificial mechanism is not the origin of culture, but, rather, that it is connected to something like original sin” (154). For, Szakolczai argues, “if human culture as such was generated by the sacrificial mechanism” (159), this logically implies the theologically unacceptable view that Christ was redeeming us from a mistake that God made in creating us this way in the first place. For there is a logical connection between two actually and really historical “event-experiences: the ‘original sin’ [whatever it was] and the epiphany of the Son of God” (159). “The historicity of Redemption, or [if you will] the revelation of the Trinity” (159) can make sense, Szakolczai argues with terrifying logic, only if there actually was such an “original sin.” The rest of this chapter is devoted to demonstrating that there is indeed historical evidence/indication of such an “event-experience” not just in the “quasi-mythological narrative of Genesis chapters 2 and 3” (159), but also in (1) the 15,000 year-old shaft-scene cave painting of Lascaux, and (2) in the Satapatha Brahmana, one of the oldest books of Hinduism.

It is impossible to sum all this up in a few words, for each of these nine authors has, with broad brush strokes, sketched out a position that would take a whole book to begin to develop properly. I have tried to indicate one of the ways in which each of the authors has tried to break new ground in our understanding of mimetic theory and its implications. This makes it a demanding book, for some of the questions it raises not only challenge “traditional” assumptions; they are also questions that often need further refinement. Struggling with them has been for me an enlightening experience. For Girardians, for those interested in mimetic theory, this is an extremely important book.

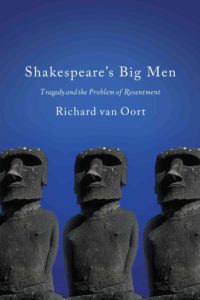

Generative Anthropology and Mimetic Theory on Shakespeare

Review by Andrew Bartlett

Kwantlen Polytechnic University

Richard van Oort, Shakespeare’s Big Men: Tragedy and the Problem of Resentment. University of Toronto Press, 2016. Pages 238.

Richard van Oort, Shakespeare’s Big Men: Tragedy and the Problem of Resentment. University of Toronto Press, 2016. Pages 238.

Any member of COV&R who works in Shakespeare studies or enjoys the great tragedies, who has been impressed by Girard’s interpretations in A Theatre of Envy, or who seeks a deeper understanding of mimetic theory’s extension in generative anthropology should place this book high on the “must-read” list. Active in the dialogue between Girardian scholarship and generative anthropology for some time now, Richard van Oort continues that lively dialogue here.

What is “the problem of resentment” in the title? Resentment is the universal human experience of exclusion from scenic centers of significance. With Girardian thinking, the scenic center as occupied by a scapegoat victim of collective violence, whose presence shocks us into peace in Girard’s famous first moment of non-instinctual attention, can become curiously inert. Not so with generative anthropology, where the vulnerable center is endlessly contested, and according to which no such shocking into peace by an unconscious mechanism of collective violence occurs anyway; collective murder in and of itself has no quasi-magical effect. Rather, human consciousness emerges with the individual’s self-representing consciousness of mimetic competition. And hoping for lasting peace from others is delusional: the best we can hope to achieve is a better awareness (maybe, God willing, control) of our resentments. We cannot all occupy the scenic center at once, and we resent whoever does occupy it: “As always, the centre is the locus of competing desires” (41). Consider how at academic conferences (COV&R included) the asker of the question-from-the-floor who goes on too long arouses resentment and the desire that he finish and sit down. We desire the absence of the one we resent.

Van Oort analyzes with a cautious, subtle patience the scenic resentments of the great Shakespearean protagonists: Brutus resents the centrality of Julius Caesar, Hamlet that of Claudius, Iago that of Othello, Macbeth the centrality of others who threaten his murderously-won crown. Shakespeare is operating in a context dominated by the neoclassical aesthetic: the moral equality of all before the Christian God has opened the classical center up to anybody worthy of occupying it. If we rush in to cheer this proto-democratic opening of the center without recognizing the pain of responsibility that comes with occupying it, our celebration is naïve. Shakespeare’s big men are not naive. They owe their greatness to their knowledge (however mixed with tragic self-deception) of what they would like to do, are doing, have done: “Centrality is never a foregone conclusion for the Shakespearean hero. On the contrary, the tragic action unfolds as an ambivalent and dangerous quest to achieve it” (163). For Shakespeare’s big men, “it is the internalization of the classical aesthetic’s unproblematic opposition between centre and periphery that defines the modernity of the Shakespearean protagonist” (137). The modernity of the great tragic soliloquies continues to fascinate us today because they are powerful evocations of the resentful self on the periphery seeking a way to justify desires to usurp the public center. But the modernity of Shakespeare’s big men is not romantic: the neoclassical protagonist cannot yet “make himself the source of a wholly personal aesthetic” (152). Van Oort highlights the way “[t]hey are condemned to suffer the sacrificial agon inherited from the ritual scene” (186), where “ritual scene” indicates a cultural system not dominated by market exchange. They would not be satisfied with hypocritical fantasies of “ignoring” the desirability of the public center in the manner of a Rousseau.

Van Oort makes this claim during his analysis of Julius Caesar: “By tracing the conspiracy back to its source in resentment, Shakespeare shows us that the origin of tragedy lies not without but within the individual. This idea of tragedy is radically different from that of the Greeks” (30). As a human universal, resentment might seem mechanistic, but van Oort’s analyses are surprisingly moral in content and focus. He engages in detailed dialogues with A. C. Bradley and others—such as Harry Berger, Michael Bristol, and A. D. Nuttall—whose approaches remain friendly to his principle that “Understanding a play by Shakespeare does not require that you drastically revise or modify your basic moral concepts” (3). Van Oort respects new historicism, but he does not have to flaunt archival micro-scholarship to authorize his project.

The chapter on Julius Caesar emphasizes the inner struggle of Brutus as he falls prey to the “brilliant…envy mongering” (XX) of Cassius. While Caesar’s is a “split personality, one moment full of insight, the next totally devoid of it” (32), Brutus longs for “moral clarity” but is ultimately a victim of self-deception who has failed to grasp “that resentment will not die with the sacrifice of Caesar” (39): “The Tragedy of Julius Caesar is the tragedy of becoming like Caesar. This is exactly what happens to Brutus. He gets stuck in somebody else’s tragedy” (54). Admirers of Hamlet (the character) will be challenged at every turn by van Oort’s skeptical questioning of the morality of the prince’s posturing. Van Oort judges that “Claudius is in fact the better man compared to Hamlet” (62), emphasizes “how prone to exaggeration Hamlet is” (64), and concedes nothing to Hamlet’s lament for the abused Ophelia: “Hamlet is finally able to declare his enormous love for Ophelia precisely because she is not present to make him feel ashamed of his huge hypocrisy” (70). Unless we critically distance ourselves from an unqualified admiration of Hamlet’s rebellion and its powerful rhetoric, we cannot hope to understand the less glamorous ordinariness of his resentment. Similarly, van Oort invites us to notice that Iago’s resentment, “cold and mean” and with “nothing grand or imposing about it” (100), is nonetheless, like Hamlet’s, a resentment that precedes any explanation of it. Shakespeare’s brilliance shines more clearly if we concede that Iago represents the resentment of Othello not just to the audience, but for the audience—on our behalf. We may register the “decadence and sentimentality” (118) of Othello’s wooing speeches.

Van Oort notices the absence of Macbeth from A Theatre of Envy: “Girard regards Julius Caesar as the definitive example of sacrificial violence, but in many ways Macbeth would be a better example” (156). Certainly, Macbeth more explicitly than the other tragedies stages the chaos of the failed state, the closest we can come to an experience of total cultural undifferentiation. Van Oort highlights the way “Macbeth’s greater evil is accompanied by greater interiorization” (137), that interiorization dramatized by visions, delusions, and a subjection to prophetic cursedness: “Macbeth’s guilt emerges in vivid representations of horror” (141). While Hamlet “embraced the distraction provided by the word,” Macbeth by contrast “fears [the word] and strives to repress its hold on his imagination” (144). Finally, Coriolanus, in the sense that he is “obviously superior, and so obviously aware of his superiority” [162], makes the biggest of Shakespeare’s big men. Unlike Hamlet’s, his resentment consists in the warrior’s contempt for mere politicians and plebs. He does have a brief self-reflective victory over himself when he shows mercy to his mother, wife and son at the gates of Rome. But the victory is temporary, and the mostly unselfconscious Coriolanus exposes with the bleakest irony the paradox of the inseparability of admiration and resentment: “After Coriolanus, Shakespeare turned from the tragic scene, in which the protagonist’s monstrous desire for centrality is punished, to the romantic scene, in which desire becomes the occasion for the hero’s redemption” (161).

Some readers of A Theater of Envy disapproved of Girard’s investment in a two-audience thesis for understanding the plays (mimetic insight for those in the ironic know, blood and death for ignorant groundlings). Van Oort invests in a similar structure, when, following Harry Berger (another Shakespeare scholar who deploys Girardian concepts), he separates the experience of the theatregoer from the activity of the critic: “I think it is self-evident that criticism depends upon the possibility of disengaging from the immediacy of dramatic experience…. Criticism is thus intrinsically ironic, in the sense that it theorizes the dramatic experience” (124); “It is only by appreciating the irony of tragedy, in which the suffering of the central protagonist is a condition of our identification with him, that we can gain insight into the problem of resentment” (xi; cf. 155). Low Joe the theatregoer is not high William the critic. And yet we are all Joe, and van Oort nudges us toward awareness that tragic form, even in the high art of Shakespeare, satisfies ignoble appetites: “We get to feel indignant with Brutus against Julius Caesar, or with Hamlet against Claudius. And when we are finished with our feelings of indignation, we do not have to suffer for indulging those violent emotions. Indeed, the protagonist himself is offered as a sacrifice. He pays for the crime of our resentment” (88-89). Resentment’s universality means that the artist, as much as he must create the imaginary resentments of his characters, must direct the real resentments of those in the audience who thirst for the satisfactions of spectacular violence (cf. 46, 68, 103, 106, 118, 130-31).

Van Oort is respectful of Girard’s interpretations at every turn, and his dialogues with Girard are multiple and searching. However, significant differences persist. For Girard, Shakespeare is great because he understood mimetic desire several hundred years before Girard himself did. For Girard, scapegoating proper happens without human consciousness participating in it; precisely because of that nonparticipation of consciousness, sacrificial re-enactors of founding violence are strategically forgetful, attempting cover-ups, participating in “myth.” For van Oort, by contrast, Shakespeare is great not because he exposes the mechanisms of mimetic desire and sacrificial violence but because he explores with a thoroughness unmatched in Western theatre the universality of resentment and—more crucially—the enmeshing of tragic form and resentment. For van Oort, full engagement with Shakespearean tragedies requires attention both to the variegated self-consciousness of its resentful protagonists and to our own resentments: “Resentment is indeed a central problem…for all humanity. But this problem cannot be reduced to an opposition between revenge and no revenge that we moderns must face up to” (18). Resentment is anterior to violence because language, the sine qua non of human consciousness, emerges in the consciousness of resentment (not non-consciously as a gradualist by-product of scapegoating activity): “To experience resentment one must be a language user capable of interpreting the world in terms of a symbolic-aesthetic scene that exists in the first place in the individual’s imagination” (168; cf. 76).

I will confess a little frustration at the tantalizing quality of certain allusions to “the forces of love” (182; cf. 88), which van Oort does not elaborate with any description of what love looks like, or how to recognize and cultivate it in a world saturated by resentment. How can practitioners of generative anthropology argue that love is the deferral of resentment, and on the other hand that imagining (representing) violence before performing it is somehow morally preferable to the enactment of real violence? A Girardian who wishes to “privilege” the Christian revelation might counter that an asceticism eschewing the violent imaginary is one of the disciplines those called to love must practice. Let us grant that we as consumers of tragic art, like Portia whose love ultimately fails her and Brutus, are “swept up in the tragic action” (46) and that it is a “necessity of tragic form that we identify with Brutus” (46). One response to such sweeping necessities might be the not wholly irresponsible quibble: well, so much the worse for Portia and Brutus and Shakespeare and tragic form. They cannot be expected to perform as the gospel does. Then again, few love the Puritan who would shut down theaters. What to do? I do believe one of the deepest questions that can be asked in the dialogue between the thought of Eric Gans and that of Girard is whether Gans’s insinuations that we should interpret the gospels as tragedy (perhaps a tragedy of innocence in Northrop Frye’s categories?) and experience the Christ figure primarily as an aesthetic figure can ever be reconciled with Girard’s radical opposition between “gospel” and “myth.”

Regarding the value of Richard van Oort’s work, however, there is no question. This gracefully written, easily followable, big-hearted book deserves all the attention we can give it. It would be a waste and a crime to neglect its riches. Anybody interested in Shakespeare and mimetic theory should order and read and share it with friends and scholars.

Desiring with Redeemed Imagination

Review by Jeremiah Alberg

International Christian University

John F. Kane, Building the Human City: William F. Lynch’s Ignatian Spirituality for Public Life. Foreword by Kevin F. Burke, S.J. Eugene: Pickwick Publications, 2016. Pages 265.

John F. Kane, Building the Human City: William F. Lynch’s Ignatian Spirituality for Public Life. Foreword by Kevin F. Burke, S.J. Eugene: Pickwick Publications, 2016. Pages 265.

Let me begin by briefly noting that with the encouragement of both the Editor and the Book Review Editor of the Bulletin, I am reviewing a book here that does not deal directly with René Girard or mimetic theory, but I think is still of interest to members of the Colloquium. I appreciate the support of Curtis and Matt in this.

In this book John Kane is doing more than retrieving the thought of a significant figure in twentieth-century reflection on Christianity and culture. He is carrying forth the program of “building the human city” in which William Lynch so deeply engaged and about which he so beautifully wrote. Kane is also asking others, as Lynch has done before him, to join this enterprise.