Mimetic theory gathers new and traditional insights about what it is to be human into a powerful set of concepts for understanding human relationships and culture. It is often expressed through three main ideas.

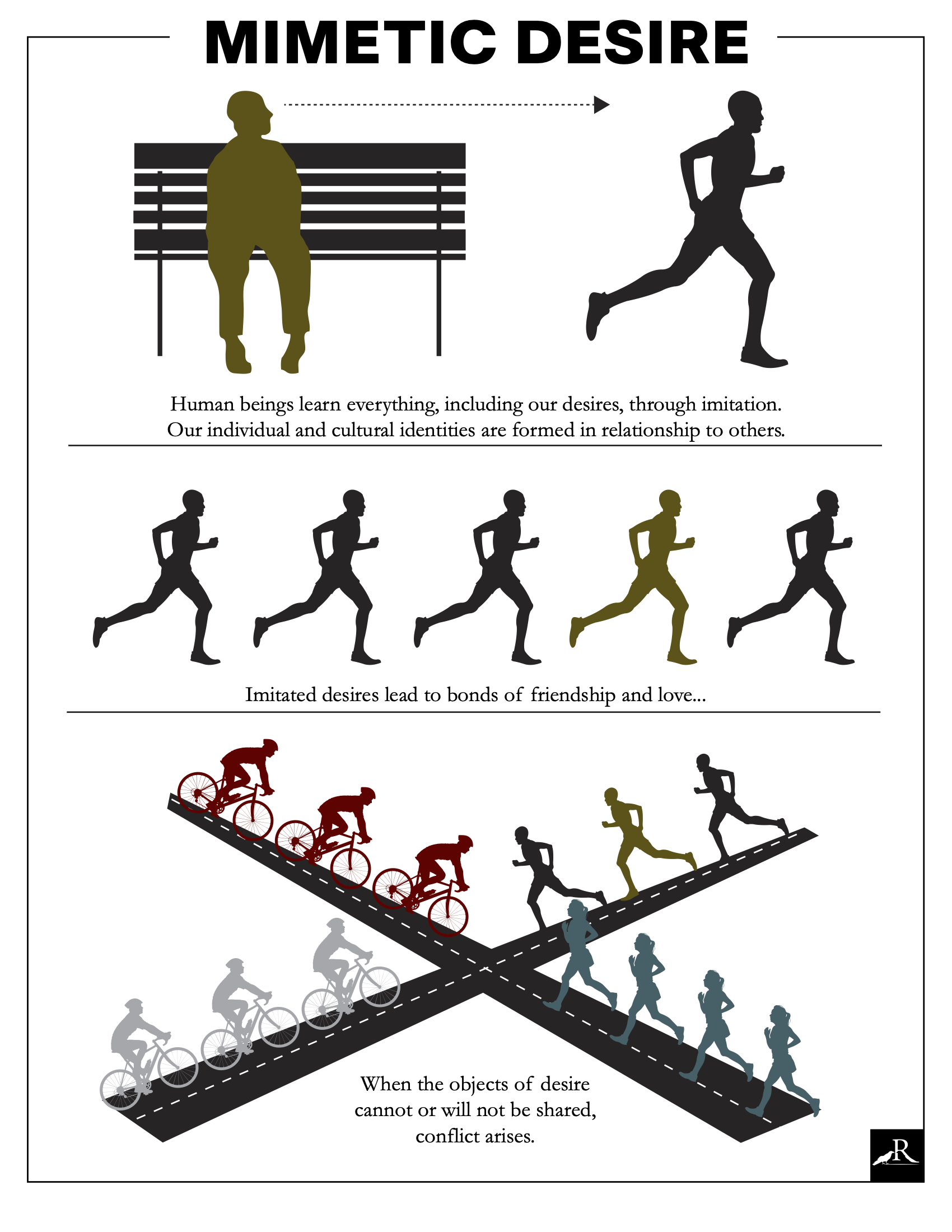

1. Mimetic Desire: All human desire imitates the desires of others, almost always without awareness. The term “mimetic” indicates that this imitation is not conscious. Mimetic desire frees us from acting merely out of appetite or instinct and makes friendship and other kinds of human flourishing possible. But it also leads to rivalry and is the primary cause of human violence. [Link to section below on mimetic desire]

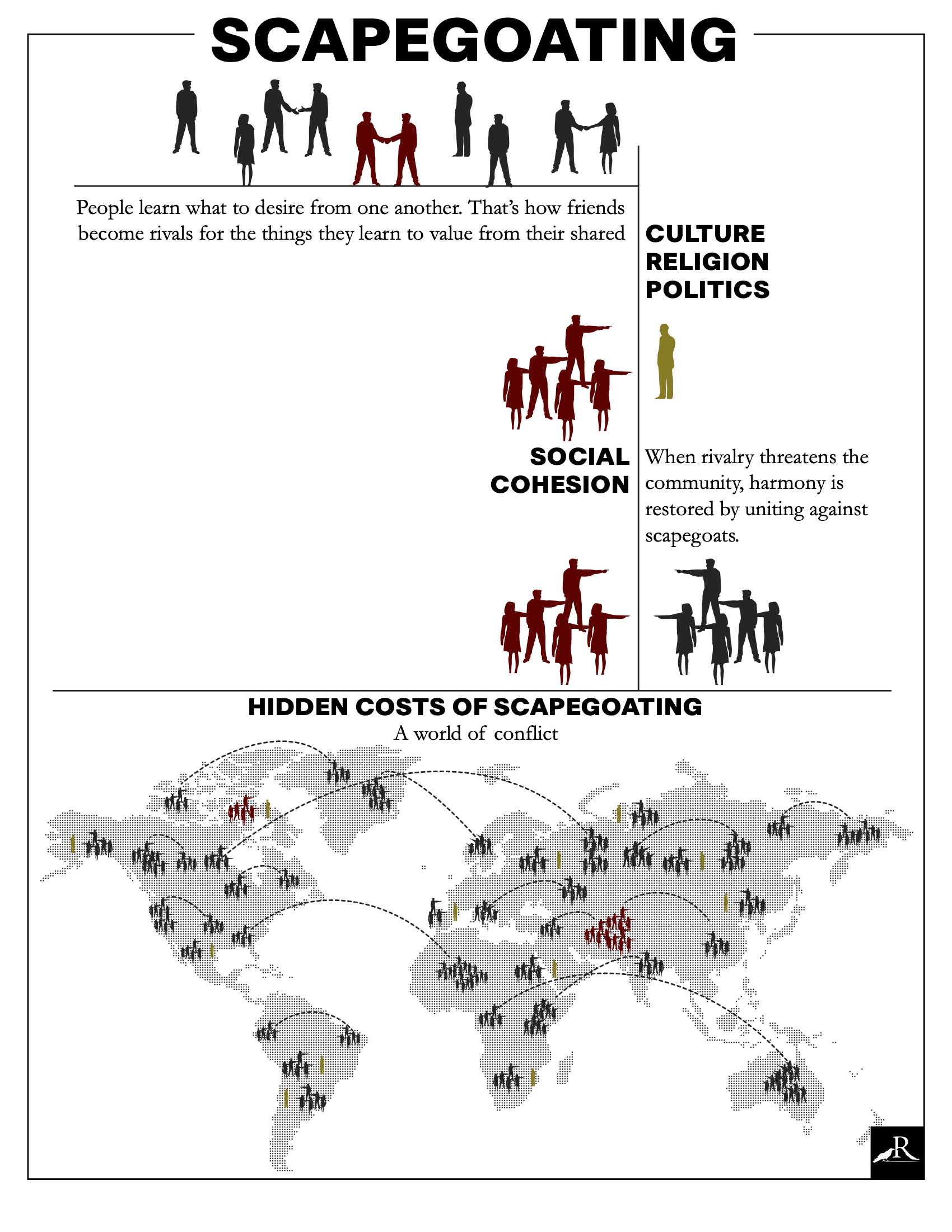

2. The Scapegoat Mechanism: Mimetic rivalry tends to spread until everyone is drawn into a crisis of violence. Human groups have, however, escaped complete self-destruction by uniting, mimetically, against an arbitrary victim who is seen as guilty of causing the crisis and eliminated. Chaos turns suddenly to order and a temporary reprieve from violence. Repetition of the scapegoat mechanism, though not understood, becomes, through sacrificial religion, the basis of all social and political order. [Link to section below on the scapegoat mechanism]

3. Revelation: In the long process of mimetic desire and the scapegoat mechanism coming slowly to light through stories told from the perspective of victims rather than persecutors, the Judeo-Christian scriptures have been especially influential. Once exposed, however—once victims are seen as essentially arbitrary—the scapegoat mechanism can no longer minimize violence. The modern world is shaped by the simultaneous proliferation and exposure of mimetic violence and scapegoating. [link to section below on revelation]

Mimetic theory is an interdisciplinary research program across the humanities and sciences as well as a basis for practical peacemaking and community building. The Colloquium on Violence & Religion brings scholars and practitioners together.

More videos on mimetic theory [link to COV&R YouTube channel]

The Big Picture

René Girard’s mimetic theory began with an understanding about desire and blossomed into a grand theory of human relations. Based on the insights of great novelists and dramatists – Cervantes, Shakespeare, Stendhal, Proust, and Dostoevsky – Girard realized that human desire is not a linear process, as often thought, whereby a person autonomously desires an inherently desirable object (Meredith desires McDreamy). Rather, we desire according to the desire of the other (many women are attracted to McDreamy, suggesting to Meredith that he is irresistible).

Mimetic desire leads to escalation as our shared desire, by mutual feedback, reinforces and enflames our belief in the value of the object. Moreover, the original subject and model become also obstacles to one another, and now also imitate each other’s adversarial behavior. Over time it may happen that the original object of desire slips from attention, and only the hostility of the opponent is emulated. As this mimetic desire and rivalry spreads in a social group, an escalation ensues that can lead to a war of all against all.

According to Girard, the primary means for avoiding total escalation and destruction came through what he calls the scapegoat mechanism, in which violence against a someone who is different from the others, such as one with a disability or a foreigner, becomes a model for the rest of the group. The fight of all against all turns into a fight of all against one, who is blamed and excluded or killed. Aggression disappears along with the supposedly guilty victim, and a calm unanimity and social order mysteriously return to the community. Achieving social order in this way is only possible, however, if the excluding parties unanimously believe that the person or group expelled is truly guilty or dangerous.

Girard’s examination of different “myths of origin” revealed that scapegoats, regardless of their actual crime, have carried the weight of all of the community’s transgressions. Read inside out, these stories reveal much about archaic societies attempts’ to curtail violence and restore order in a fragile world with no civil structures. All of human culture, according to Girard, is built upon the edifice of this scapegoating, which is later emulated in a ritual form: the same action that has led to peace once mysteriously, is now performed intentionally to recreate its effect. Sacrificial religion, as found in early history throughout the world, is instituted. This reading of culture, inspired by an insight into of the innocence of the victim made available in the Jewish and Christian scriptures as well as other sacred texts and implied in some literary works such as Greek tragedies, has made possible an increased awareness of this mechanism and its aftereffects, so as to interrupt these processes and achieve a different kind of peace.

Let’s revisit these three interconnected movements described and analyzed by mimetic theory—mimetic desire, the scapegoat mechanism, and revelation—in more detail.

Mimetic Desire

We rely on mediators or models to show us who and what to desire, mostly without knowing it. Indeed, we usually think our desires come from spontaneously from ourselves, or from what we see as desirable. Mimetic desire enables collaboration and friendship. The problem is that it also leads to conflicts because a model, particularly when not seen as such, can quickly become a rival who competes with us for the same object. For example, let’s say that I am a graduate student in the field of psychology, and I am desperate to work with the highly esteemed professor in our department, Dr. Jones. Dr. Jones seems to have it all – respect, a thriving research lab, and many collaborations with the world-renowned psychologist, Dr. Smart. For a good year, I work hard to be just like Dr. Jones – I copy her research methods, attend similar conferences, and work at a pace that mirrors Dr. Jones’. As time goes on, my research practice takes off, and soon it is I and not Dr. Jones who is being asked to headline conferences with Dr. Smart. It’s not long before Dr. Jones, who had taken pride in my successes, comes to think of me as a rival for opportunities to work with Dr. Smart. Dr. Jones may even accuse me of a new desire – that of wanting to destroy her career and she may soon act to undermine my career rather than encourage it. Collaboration has turned to rivalry and friendship into enmity.

We rely on mediators or models to show us who and what to desire, mostly without knowing it. Indeed, we usually think our desires come from spontaneously from ourselves, or from what we see as desirable. Mimetic desire enables collaboration and friendship. The problem is that it also leads to conflicts because a model, particularly when not seen as such, can quickly become a rival who competes with us for the same object. For example, let’s say that I am a graduate student in the field of psychology, and I am desperate to work with the highly esteemed professor in our department, Dr. Jones. Dr. Jones seems to have it all – respect, a thriving research lab, and many collaborations with the world-renowned psychologist, Dr. Smart. For a good year, I work hard to be just like Dr. Jones – I copy her research methods, attend similar conferences, and work at a pace that mirrors Dr. Jones’. As time goes on, my research practice takes off, and soon it is I and not Dr. Jones who is being asked to headline conferences with Dr. Smart. It’s not long before Dr. Jones, who had taken pride in my successes, comes to think of me as a rival for opportunities to work with Dr. Smart. Dr. Jones may even accuse me of a new desire – that of wanting to destroy her career and she may soon act to undermine my career rather than encourage it. Collaboration has turned to rivalry and friendship into enmity.

René Girard called this a “mimetic rivalry” to highlight the movement from a model-subject to a model-obstacle relationship. This shift occurs when desires converge on an object that cannot be shared (such as a job, a first place prize, or a lover) or that the rivals are unwilling to share (such as fame or working with Dr. Smart). It’s important to note that the two rivals are now models for one another, enflaming each other’s desire to work with Dr. Smart by desiring to possess it exclusively. Each is now a model-obstacle for the other, something both would vehemently deny. Each will claim that their desire is autonomous and the other has betrayed their friendship out of plain wickedness. Girard has pointed out that the problem is not that desires are mimetic, but that in clinging to the mirage of our own originality we become prone to blaming others rather than recognize our complicity in mimetic rivalries.

Link to the annotated bibliography of works by Girard on mimetic desire.

Understanding desire and conflict in this manner highlights the interdependent nature of human motivation and informs fields such as literature, psychology, sociology, economics, political science, psychotherapy, communication studies, conflict management, and more. Mimetic theory calls into question well-known principles such as realistic conflict theory, rational actor theory in economics, and many theories in psychology which presuppose that behavior depends on an autonomous, rational individual. Mimesis and Science: Empirical Research on Imitation and the Mimetic Theory of Culture and Religion, edited by Scott R. Garrels, gathers the work of influential scholars working at the intersection of mimetic theory and several fields.

The Scapegoat Mechanism

The second movement in mimetic theory is the scapegoat mechanism. As rivals become more and more fascinated with each other, friends and colleagues may be mimeticly drawn into the conflict as rival coalitions form. What began as a personal battle may escalate into a Hobbesian battle of all against all, threatening the cohesion and peace of an entire community. One way of solving this problem is to find someone to blame for the conflict that all the rival coalitions can unite against. This unfortunate person may or may not be guilty. All that’s required for the scapegoating solution to work is that their guilt be universally agreed upon and that when the person is punished or expelled from the community, they will not be able to retaliate. The proof of their guilt is found, once they are eliminated, in the peace that returns to the community, obtained by virtue of the unanimity against them.

The second movement in mimetic theory is the scapegoat mechanism. As rivals become more and more fascinated with each other, friends and colleagues may be mimeticly drawn into the conflict as rival coalitions form. What began as a personal battle may escalate into a Hobbesian battle of all against all, threatening the cohesion and peace of an entire community. One way of solving this problem is to find someone to blame for the conflict that all the rival coalitions can unite against. This unfortunate person may or may not be guilty. All that’s required for the scapegoating solution to work is that their guilt be universally agreed upon and that when the person is punished or expelled from the community, they will not be able to retaliate. The proof of their guilt is found, once they are eliminated, in the peace that returns to the community, obtained by virtue of the unanimity against them.

Mimetic theory allows us to see that the seeming peace thus produced is actually violent, comes at the expense of a victim, and is built upon lies about the guilt of the victim and the innocence of the community. This mechanism functioned at the origins of the human species, when this peace appeared as if by magic and was attributed the victim that had just been killed. This victim was divinized, believed to be to a visitation from an ambiguous god who came first as the terrible cause of the conflict but then was revealed to be its cure. Prohibitions emerged to forbid the imitative behaviors which lead to conflict, rituals developed that consist of a well-controlled mime of the redemptive violence against a victim (originally human, later animal or other substitutes), and myths were born as the stories that tell of how we became a people as the result of a visitation from the gods. This method of controlling violence with violence can be found in the rites and myths spread all over our planet and gave rise to human culture.

Scapegoating also operates at the level of identity. We all construct identities over against someone or something else. I’m a woman, not a man. I’m a liberal not a conservative. I’m an atheist not a believer. And most problematically, I’m good not bad. When we need some other person or group to be bad so we can maintain our sense of ourselves as good by comparison, we have engaged in scapegoating. We are using others to solidify our identity the same way a community uses a scapegoat to solve its internal conflict.

Link to an annotated bibliography of works by Girard on the scapegoat mechanism.

Though the study of scapegoating fell out of favor in the social sciences following some early acclaim, mimetic theory revives this concept and situates it as an anthropological evolution of the human need to contain conflict. Because Girard’s theory follows desire in non-human species through hominization and beyond, it provides reasons for the prevalence of scapegoating and why it has existed throughout time. The fact that scapegoating contains conflict and gives order to new cultural foundations is informing anthropologists, historians, philosophers, sociologists, political and economic theorists, and associated academics working in areas of peace studies and conflict resolution. The theory also offers explanations for organizational consultants who aid in cases of school, college, and workplace bullying. Recent wide-ranging publications include How We Became Human: Mimetic Theory and the Science of Evolutionary Origins and Can We Survive Our Origins? Readings in René Girard’s Theory of Violence and the Sacred, both edited by Pierpaolo Antonello and Paul Gifford; and Vengeance in Reverse: The Tangled Loops of Violence, Myth and Madness by Mark R. Anspach.

Revelation

When a community in the throes of conflict obtains peace through the violent expulsion of a scapegoat, they cannot perceive that it is their own unanimous violence which produced the peace. This blindness on the part of the participants with respect to what they are really doing – killing an innocent victim – is the one essential element required for the scapegoating mechanism to work. Girard points out that to have a scapegoat is not to know you have one. In other words, participants in the scapegoating mechanism hold an authentic belief in the guilt of the victim, a guilt seemingly demonstrated by the restoration of peace.

Girard thinks that the power of the biblical writings lies in “unveiling” the scapegoat mechanism. Here unveiling is, quite literally, pulling back the curtain to see that, behind all the smoke and sounds is just a small man, pulling the levers. Already the Hebrew Bible (or Old Testament) show God to be on the side of single victims being persecuted by a mob, as many Psalms and prophetic texts attest. The New Testament brings utmost clarity: the Gospels have the same structure as myths, but an entirely different perspective—a key issue for Girard. In myths we are given scapegoats concealed behind gods of both vengeance and blessing, or victims whose death promises both to heal fractured communities and to appease the gods. Yet in the gospel story we gradually learn that God is the victim, and that the victim’s blood only appeased humans, not God. Having a real event told in this particular way intends to foster conversion.

Though we think of the gospels as telling a story about God, Girard follows Simone Weil in showing that the gospels are as much about us (humans) as about God. And the true power of the story, or the conversion, lies in the permanent alteration in the way we read not only the gospel story, but everything else. Instead of reading through a sacrificial lens, we read through a forgiving lens, realizing that we, both on an individual and on a social level, have been involved in a multi-generational process of victimizing and expelling others. And that God has nothing to do with this violence.

Mimetic theory begins with the human shape of desire and does not leave the human even when it engages with theology. The turn to theology in its third movement is not an escape from the terrestrial realm. All of its “theological” insights can be seen working themselves out on the anthropological level. Girard thought humans had been so deeply habituated into patterns of escalating violence, and the scapegoat mechanism to be so perfectly self-justifying, that he concluded it necessary for there to be some real, supernatural interruption to achieve human redemption.

Link to an annotated bibliography of works by Girard on revelation

Many theologians and religious educators draw upon the insights of mimetic theory as a way of understanding God as the victim, the fundamental human tendency toward scapegoating, and what all of this means in the pursuit of cultural order, justice, and reconciliation. Mimetic theory is having a profound impact in religious studies, biblical hermeneutics, Christian theology, studies of sacrifice and world religions, and peace studies.

Bibliography of books on mimetic theory categorized by subject area

The Raymund Schwager Memorial Award Winners

The Colloquium on Violence and Religion offers an award of $ 1,500 shared by up to three persons for the three best papers given by graduate students at the COV&R annual meeting. Learn about these scholars and the topics they address.

Learn More About Mimetic Theory

For a more complete introduction to Girard’s work see René Girard’s Mimetic Theory by Wolfgang Palaver; Discovering Girard by Michael Kirwan; and The Girard Reader by René Girard, James G. Williams editor. The COV&R YouTube channel contains videos by a wide range of mimetic theory scholars and practitioners. Mimetic Theory 101, a four part video series with Wolfgang Palaver and Adam Ericksen, provides a thorough overview of mimetic theory.

To engage directly with the authors of the books mentioned here and many others working with mimetic theory, become a member of COV&R today.

How to cite this page:

APA Style (7th ed):

What is Mimetic Theory? (2025, February 3). Colloquium on Violence & Religion. https://violenceandreligion.com/what-is-mimetic-theory-updated-page/

Chicago Style (17th ed):

Colloquium on Violence & Religion. “What Is Mimetic Theory?,” February 3, 2025. https://violenceandreligion.com/what-is-mimetic-theory-updated-page/.

MLA Style (9th ed):

“What Is Mimetic Theory?” Colloquium on Violence & Religion, 3 Feb. 2025, https://violenceandreligion.com/what-is-mimetic-theory-updated-page/.