No. 56 May 2018

Contents

Letter from the President, Jeremiah Alberg

Editor’s Column, Curtis Gruenler

COV&R Annual Meeting, Stephen McKenna

COV&R Sessions at the American Academy of Religion, Grant Kaplan

Letter from…the Dutch Girard Society, Berry Vorstenbosch

Cynthia Haven, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, reviewed by Andrew McKenna

Letter from the President

Come to the Annual Meeting

Jeremiah Alberg

International Christian University

The gist of this report can be reduced to one word: Come! Come to Denver. The fatted calf has been killed, the banquet is prepared, we await the invited.

I believe that we have a really strong Conference planned. There have been some significant obstacles to overcome, but we have managed to find a beautiful venue with interesting excursions (Shakespeare!) and great lineup of plenary speakers. Now we need you.

All of us in COV&R know what really makes the annual Conference special—it is meeting each other. The mealtime discussions, the chats at the receptions, the conversations at the coffee breaks. Meeting new people, getting reacquainted with people we have met at previous conferences, and seeing old friends. These are things that make COV&R conferences so valuable. So now we need you. Without you the Conference will be poorer, less special, less vibrant. Each member contributes when he or she comes to the Conference.

I have heard from people who, having had to miss a few conferences, return to one and then say: “I have been away too long. I need these meetings. They give me energy and hope.”

COV&R is in a time of transition. The early members who started and built the organization are passing on and the new members are taking on more and more of the responsibilities for its continuation. We have symbolic instance of this in this year’s conference. Andrew McKenna—one of COV&R’s stalwarts and now its éminence grise—organized the 1995 Conference held at Loyola University (final four in this year’s NCAA basketball tournament) with the theme “Violence, Mimesis, and Responsibility.” Bill Clinton was President; O. J. Simpson was found not guilty of murder; the Million Man March in Washington took place. Now 2018 brings us Donald Trump as President, O. J. Simpson being released from prison, and the Women’s March on Washington. The Conference organizer is Stephen McKenna, nephew to Andrew (see Stephen’s invitation below). As we work to realize this Conference we are also laying the groundwork so that one of Stephen’s children or nieces or nephews can organize the 2041 Conference, when, no doubt, Malia Obama will be President.

So again, please come. This Conference is one link in a chain that stretches back to 1991 in Stanford through such cities as Boston, Innsbruck, Paris, Ottawa, Amsterdam, Tokyo, and Melbourne to who knows where. Along the way there have been many challenges and a few mistakes, but that is what makes the wonderful moments shine all the more brightly.

I look forward to seeing you in Denver on July 11th.

Editor’s Column

Friendship and Truth

Curtis Gruenler

Hope College

By way of an encouragement to come to this summer’s annual meeting, I would like to offer a teaser for the talk I am planning to give. I am still thinking about friendship and positive mimesis, now in connection with knowledge. It seems to me that mimetic theory has implications for the social element of knowledge, whether one takes a strong view that all knowledge is socially constructed or a weaker view of social epistemology (and I would be interested in some conversation about what view might better fit with MT). To the extent that knowledge is a social construct, locating the origins of social organization in sacred violence has a lot to say about how knowledge gets warped away from truth, starting with the mythological misunderstanding of victims as gods. But might MT also have something to say about what kind of relationships lead to well-constructed knowledge, that is, to truth?

I think the ideals of friendship are the most traditional way of talking about relationships that help us know truth. My talk will suggest resources in classical views about the definition of friendship as mutual concern for another’s well-being and the consequent emphasis in ancient authors on virtues like frankness against the dangers of flattery and rivalry. I will try to place friendship within keynote speaker Paul Dumouchel’s account, in The Barren Sacrifice, of historical changes in solidarity groups under the influence of Christianity and rise of the nation-state. There are lots of other connections I’d like to explore, such as the liberal arts as a structure of intellectual friendship, recent social science research on the cognitive dimensions of friendship, and literacy as a means of nurturing friendships for the sake of knowledge.

Perhaps thinking about friendship can be one way of developing a response to MT’s diagnosis of “Religion, Politics, and Violence ‘after’ Truth.”

Archiving: The first issue of this Bulletin that was published in the current, online format, number 48 from May 2016, is now available in pdf format from the Philosophy Documentation Center, where previous issues in print format are also available. Our tentative plan is to keep archiving them in this way after they are one to two years old and then remove them from the website. If you have any comments about availability or format, please let me know.

Directory of Graduate Programs: As announced in our previous issue by Executive Secretary Martha Reineke, COV&R would like to develop a directory of graduate studies in mimetic theory. If you are involved in a program you would like to be included, please see the announcement and send her your information.

The Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence has published its second issue, which includes English translations of three interviews with René Girard from 2002-2008 previously available only in French as well as articles taking a Girardian approach to the theme “Philosophical Inquiries into Modern Jihadism” and three reviews of books in the MSU Press series on mimetic theory.

Blogwatch: COV&R members should by now have received copies of Cynthia Haven’s wonderful and moving biography of Girard. (See the review below by Andrew McKenna, one of his early graduate students.) Haven also has a blog that includes matters related to mimetic theory (such as this piece by Mark Anspach) among its engaging literary miscellany.

Forthcoming Events

COV&R Annual Meeting

Stephen McKenna, Catholic University of America

For all the twists and turns on the rocky road to Denver, it still feels like just last week I was treading the Cahokia mounds in St. Louis at the 2015 COV&R conference when Jay Alberg stealthily took me aside to say, “I’d like to ask you something.” I narrowed my eyes and replied, “I suspect I know what’s coming.” To which he said, “If you suspect you know, then you know. So just say yes!” Little did either of us know what lay in store—that two years later we’d be working on a conference to take place far from my home campus (lately gripped in crisis, as you may have read). But it has been an honor and a privilege, and we now have a great meeting in the offing, with four excellent plenary speakers, an abundance of outstanding presentations, panels, and workshops, participants from six continents, and a lovely setting in which to continue our conversation. (If you or someone you know missed the submission deadline, the schedule hasn’t been locked down yet, so query me.) I want to thank all of the members, regular and executive, who have been so extraordinarily patient and helpful as we undertook to relocate the conference. We should be grateful to the people at Regis University, too, and most especially to Fr. Kevin Burke, S.J., whose gracious “Yes” truly saved the day. Now it’s your turn to say “Yes” and come to Denver for what promises to be a great four days of interdividual thinking, colloquy and conviviality.

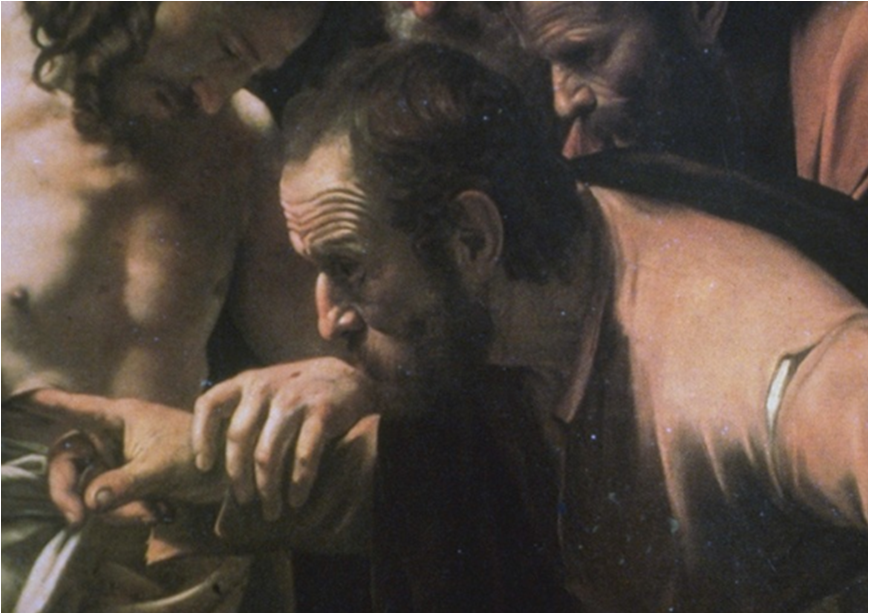

Speaking of conversations and positive mimesis, I recently had a fruitful exchange with one of our veteran Canadian members, who wrote to ask about the image attending the conference announcement—Caravaggio’s Incredulitá di San Tommaso (1601-2). It depicts, of course, the famous event recounted in John 20:27-28. (Or does it?) My friend was fascinated, she wrote, by the fascination of the three figures, “…even though they seem to be missing the point, not so much looking directly where they should be, but looking at a part and missing the whole.” Once I had settled on “After Truth” as the conference theme, I ranged around for some time looking for an apt illustration. When I came across this picture, I instantly sensed it was right, but I didn’t contemplate it closely until later, when, fully in the throes of conference organization and suffering my own dark passages of doubt, I lucked into an invitation to correspond with a dear friend about it.

Perhaps our tendency to such careless oversight is what the picture is partially “about”—and so it is doubly relevant to our theme. The first clue to this is Thomas’s crouched stance. His rapt absorption catalyzes our own: we want to get closer and closer to see just what is “really” taking place. And yet, in total contrast, there is Thomas’s strangely stunned and dislocated stare, which, despite the surprise and amazement signaled by his wrinkled brow, points past its object, and is anyway almost completely masked under Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro palette. In our confusion over his confusion, we naturally turn to the other two apostles as helpful models—but their crossed and shadowed gazes only deepen the mystery. It seems the painter gives us thereby a partially obscured view of viewing itself, that would cast doubt on whether looking, or any Thomas-like empirical zeal for that matter, might yield ready access to truth. Look too, I suggested to my friend, at the tear in the seam of Thomas’s shirt that mirrors the wound in Jesus’ side. It seems to open and pull apart the more he stoops forward. For all its seeming triviality, this little detail is a graphic focal point of the picture, and is no mere bit of happenstance naturalism. A “rent garment,” the shirt is symbolically surcharged, a token of the grief and suffering we often undergo in struggling, like Thomas, as we grasp at truth. Yet to see this all-important tear, we have to look away from the “truth” Thomas would seek in the wound. Jesus in Carvaggio’s hands is thus the victim whose body draws us in and points away from itself. This resonates with a central ambiguity of the painting that we may have barely noticed: Is Jesus pulling Thomas’s hand towards himself, or more likely, my friend and I agreed, away–away and back towards our flawed selves and the flawed others to whom we are joined on life’s journey? Ultimately it is a question and a paradox that won’t submit to paraphrase or explanation. “There is a crack in everything; that’s how the light gets in.” The picture seems to say that belief, understanding, truth, all enter the world via such “impossible” paradox. Perhaps the ultimate paradox of the painting, in case we were feeling certain about what we are seeing, is that in the Gospel verses, Caravaggio surely knew, Thomas never puts his finger into the wounds at all, but undergoes his encounter with truth without the benefit–or the obstacle–of the crude kind of autopsy we so often long for.

For me it took a conversation with another Girardian seeker to get some better appreciation of Caravaggio’s mysteries here (though there is much more to probe, pun intended). Perhaps that, in the end, is the only way to be in the pursuit of truth. Whatever understanding of truth is being worked out in the painting, as well as between the painter and us, we can be sure only that it is a collective and thoroughly relational effort. In exactly that spirit I warmly look forward to seeing everyone in Denver!

COV&R Sessions at the American Academy of Religion

Denver, November 16–19, 2018

Grant Kaplan, AAR Liaison

Session I

Theme: “Cynthia Haven’s Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard”

Convener: Grant Kaplan (Saint Louis University)

Moderator: Grant Kaplan

Panelists: Martha Reineke (University of Northern Iowa)

Kevin Hughes (Villanova University)

Trevor Merrill (California Institute of Technology)

Response: Cynthia Haven (Stanford University)

Session II

Theme: “Rene Girard and Christian Spirituality”

Convener: Grant Kaplan (Saint Louis University)

Moderator: Chelsea King (University of Notre Dame)

James Alison (Madrid, Spain), “Interdividuals, Individuals and Fragmented Selves: How Can Mimetic Theory Help Us Understand ‘Huiothesia’”

Randy Rosenberg (Saint Louis University), “The Spiritual Texture of Trauma: Mimetic Desire, Psychic Conversion, and the Healing of the Damaged Self”

Brian Robinette (Boston College), “Mimesis, Meditation, and the Art of Creative Renunciation”

Times and locations are yet to be determined and will be announced in the AAR conference program.

Letter from…the Dutch Girard Society

On Endurance

Berry Vorstenbosch

I would like to start my briefing with a quote from James Williams’s Girardians: The Colloquium on Violence and Religion, 1990-2010: “It is remarkable that the Dutch Girard Society, which currently has only about forty people on its mailing list, has held together all these years. Those who attend come from all over Holland, so the dedication to meeting for learning and fellowship is strong.” These statements still hold. No real news from Holland, as it seems, we are simply still going strong. If I would give updates, they would at first sight concern only minor details: the mailing-list has expanded to exactly 59 people by now, and occasionally we may welcome a Belgian or German visitor at our meetings.

Yet, the enduring, persisting interest in mimetic theory, as we experience in our society, needs some reflection in itself. What is the driving force behind it, how do we get along, and what sort of questions are we confronted with? Let me first of all say that, while heading to a 40th year anniversary, we are confronted with something that could be named a true generation-shift. I think this is something that occurs in any organization that reaches a respectable age. In Williams’s Girardians, you will find the entire list of people who sparked it off in the early 80s, this Dutch thing. They are all there, our founding fathers. Reading this list, as someone belonging to this society, I must say I was shocked to find how many of them are not with us anymore.

Here I especially want to mention André Lascaris and his tragic death in the summer of 2017. If you want to say anything about “enduring” and “persistence,” André was a true model. In our circle we have at times been concerned with the “popularity” of mimetic theory, or with the decreasing number of visitors to our meetings. In order to raise the number of visitors, you may easily start to reason like a marketeer. Such worries did not really exist in the mind of André Lascaris. At one moment in his life he had embraced mimetic theory, and from then on he endured. André once made a turn onto mimetic theory and followed the course till the end. Suffering severely from Parkinson’s disease, André attended almost all our meetings up till the very summer of 2017.

Let me give another quote from the Girardians: “There are usually fifteen to eighteen people who attend. They meet about five times a year at the Free University of Amsterdam.… The gatherings are always on Friday from 10:30 to 12:30.” Yes, this basically still holds. Five times a year, still on Fridays. Still from 10:30 to 12:30, yes. The number of attendees has been fluctuating in the last years, but at the moment the number is rising again. Why? Maybe because mimetic theory is reaching new territories. Or maybe because mimetic theory is just slowly spreading. Today we also find more and more writings in which “mimetic desire” is named without any thorough explanation—to name two examples: Jonathan Sacks’s Not in God’s Name and Pankaj Mishra’s Age of Anger (those who attended the COV&R in Madrid will remember the interview with Mishra). The true endurance, the true sustaining power in mimetic theory, rests in the value of Girard’s theory itself.

Further, we feel happy to announce that we have started to organize a biennial Girard lecture. It started off in 2014 with a lecture by Hans Achterhuis about politics and violence. Achterhuis is a typical example of the way mimetic theory may endure in the intellectual world. His interest in mimetic theory figures in his 2008 publication Met alle geweld, and for his more recent book The Art of Peaceful Fighting he even contacted us to discuss the passages on mimetic theory. In 2016, the Girard lecture was delivered by Willem-Jan Otten. In his rich lecture, Otten, being a literary writer, focused on the major Dutch 17th-century writer Joost van den Vondel. For the end of 2018 a third Girard lecture is planned. Johan Landgraaf will speak about the philosophy of economy, in particular Adam Smith.

When we were officially registered as a foundation in 2009, we chose for our logo the rhizome. It symbolizes the continuing underground activity inspired by or based on mimetic theory, sending roots and shoots in sometime unexpected directions. We feel part of a larger network, and we see how the list of authors that take up an interest in mimetic theory is growing all the time. We only can endure because mimetic theory is very much alive.

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the book review editor, Matthew Packer.

The Originality of an Ordinary Life

Review by Andrew McKenna, Loyola University Chicago

Cynthia L. Haven. Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard. Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. East Lansing: MSU Press, 2018. 317 pages.

René Girard describes to his biographer his own life as “a banal enough existence for the second half of the twentieth century,” and in an earlier interview with Jim Williams, he states “I am an ordinary Christian.” Remarks such as these pose a formidable challenge to any biographer. Haven meets that challenge with ample evidence of the man’s wit, erudition, and beguiling sense of humor, which galvanized the enthusiasm of his students and colleagues when he taught at Johns Hopkins; nearly everyone in the Department of Romance Languages wanted him to direct their dissertation, whether in French or Spanish or Italian literature. After brief stints at Indiana, where he got his doctorate in history and where he was denied tenure in our “publish or perish” gristmill, and at Duke, where this virtual refugee from previously occupied France could not help to be struck by the Jim Crow culture, Hopkins became the launching pad for the dazzling achievement of his intellectual and spiritual excursion through literature, anthropology, and biblical revelation, in that order.

Haven likens him, rightly I think, to Tocqueville, whose travels through vast swaths of our younger country, under the pretense of studying our prison system, shed enduring light on American attitudes and institutions in a way that explains modern world tensions altogether, and especially our benighted individualism, a word of his genial coinage. Girard cited him tellingly a number of times. But Girard’s research exceeded his compatriot’s purview by several orders of magnitude, resulting in a hypothesis on the violent origins and sacrificial organization of human culture as such, and COV&R, which Haven strangely doesn’t mention, is but one of several research and outreach fora inspired by Girard’s thought.

Haven states that his work in the “social sciences” began during his sojourn at SUNY Buffalo, but in fact Levi-Strauss was already being read alongside of Proust under his tutelage when at Hopkins, such was the generosity of his interests and his discerning attention to non-conscious, structural valences. The variety and vastness of American universities saved Girard from the hothouse polemics and “querelles de chapelle” that consumed the energies of Parisian intellectuals, and his impressive publications soon left him free to range widely among academic “disciplines,” the highly bureaucratized arrangement of knowledge fields that always annoyed and perplexed him. Enthusiasts of his work are stuck with the shorthand term “mimetic theory” designating it, but he never used that expression. Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World begins with chapters on what he labeled “fundamental anthropology,” and later on “biblical anthropology.” Many critics are fairly scandalized by the “grand unifying theory” character of his project, its “theory of everything” air. And understandably so for an author whose biggest book draws its title from the universalist claims of Scripture. There is less narrow disciplinarity in what the French have had the wits to identify as “the human sciences,” including the humanities and social sciences. Girard remains an outlier for having embraced them all in his research. Admittedly “self-taught,” his genius has been to perceive relations of similarity where most others have been harping on differences.

With the discovery of mirror neurons, the neo-cortical hardware of our mimicry, even the biological sciences are implicated. There can hardly be a more outlandish title for a book than Evolution and Conversion, where Girard interweaves the insights he draws from Darwinian science and biblical revelation while updating the explorations in anthropology and evolutionary theory of earlier works, and successfully eluding the aberrations of creationism. This volume of conversations—a congenial format severally employed by him—is a forthright profession of faith, including faith in Darwinian science: “I don’t see why God could not be compatible with science. If one believes in God, one also believes in objectivity. A traditional belief in God makes one a believer in the objectivity of the world.” Girard has regularly insisted on the properly scientific ambition of his work, which has borne fruit in a number of volumes published in the splendid MSU series, underwritten by the Imitatio Foundation as Studies in Violence, Mimesis and Culture, in which Haven’s book appears. (See especially, How We Became Human and Mimesis and Science in this series, which update Haven’s coverage in this regard.)

The oft-cited dictum of Archilochus, “The fox knows many things; the hedgehog knows one big thing,” applies to Girard. Roberto Calasso in his important book, The Ruin of Kasch, labels Girard as a hedgehog, and, pace Haven, I think he got it right. Like Darwin in his realm, like Freud and Marx and Einstein in theirs, like Jesus for that matter—God’s love for his creatures has to be our love, if we are to survive at all—Girard has said that he has one idea, one intuition as he calls it: mimesis. Like every great thinker, Girard is a monist. Everything he has worked out over several overlapping research fields stems from that easily verifiable fact about the behavior of humans—and animals up to the point where instincts prevent mimetic desire from careening willy-nilly into lethal violence.

Where humanist literary critics focused on a writer’s difference, as his or her “genius,” Girard left the reservation with his first book, Deceit Desire and the Novel. He detected a pattern of mimetic desire unveiled in the works of our greatest novelists. And where anthropologists, resisting ethnocentrism, were insisting on local knowledge, he uncovered in Violence and the Sacred an unvarying sacrificial dynamic spanning the myths and rituals of traditional cultures worldwide, whose delusions about sacred violence, very nearly apprehended in Greek tragedy, are fully revealed in the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures (Things Hidden). So the human self-understanding which our greatest literary works attain is continuous with Revelation. Dostoevsky was not alone in envisioning the properly prophetic ambition of his novels, and history, alas for the worse, has born them out as we cannot fail to observe in this apocalyptic phase of our species. Accordingly, several scholars have remarked upon the prophetic character of Girard’s work, beginning with his first book, which he rewrote entirely after his own experience of conversion.

Girard’s stunning breakthrough is adroitly summarized by Haven reporting a conversation with Jean-Pierre Dupuy about resistance to Girard’s thinking:

Reason #1: “He believes in God, and he says it.” Dupuy said that laïcité in France means in practice, “a public hatred of religion,” which makes Girard a jolting departure of the norm…. Reason #2: “He believes in the possibility of a science of man.” Post-structuralism, and other “isms,” have denied the possibility of knowing truth, or at least devalued it…. Reason #3: Finally, what he calls the last straw: “#1 and #2 are the same reason.” That is, “if it’s possible to reach the truth, it’s because truth is given by God, and the incarnation of God is Jesus Christ.”

Haven correctly adds that the same resistance is pervasive among the “bien pensants of our own country.” We PhDs are much too nice, too benignly pluralist, to hold to believing anything rigorously, except perhaps to our skepticism about absolute truth—an idea, nonetheless, whose time has come, and to our immanent peril. “Truth,” Girard asserts in an early essay on Proust, “is one,” and we must wonder how it could be otherwise—and be true. Girard’s trenchant formulations here and there have their own rationale, ironically modest and soundly Popperian: “Theories are expendable,” he says to Haven, “They should be criticized. When people tell me my work is systematic, I say, ‘I make it as systematic as possible for you to be able to prove it wrong.’” For all that, his thinking does not lead up to a system, psychological, socio-political, religious or philosophical; rather, as Cesáreo Bandera shows in The Sacred Game, the victimary hypothesis is a “system breaker,” the violent closure of the scapegoat mechanism that drives social systems even today being irrevocably punctured by the cross.

I would cite yet another reason for resistance here: the sheer simplicity, the plainness and accessibility of his thinking, its parsimony, which Eric Gans has so correctly insisted on, namely, its ability to explain much with little. It cannot be that simple, many say; it’s what the Scribes and Pharisees said of the know-it-all Nazarene whose death they pursued so steadily, only to have their plot against him work for all time in favor of his teachings. This is the meaning that Girard has attached to Paul’s eschatological assertion about “the wisdom which none of the rulers of this age has understood; for if they had understood it they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.” In his meditations on Romans Gil Bailie genially observes that resistance to revelation is part of revelation, whereby he clarifies, I think, the epistemic claim of John’s gospel: “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness cannot comprehend it”—cannot master it, overcome it; au contraire, the light reveals the darkness as never before. The romantic lie is a world of darkness and light, the latter being the privilege claimed by the modern self; it is the world, very much our own especially these days, of us vs them. Girard everywhere dispels this Manichean dualism. For mimetic realism (to use Bob Hamerton-Kelly’s defining expression), God’s light presides over the opposition, the agon, of light and darkness. Imagine light and dark in opposing squares, and light alone glistening above and all around them. There is no dark side to the God of Israel whom his son illuminates to the very end, despite and because of the violent cries of a lynch mob and the scandalized panic of his very own disciples. Alert to paradoxiphobes: avoid Girard.

This is not an intellectual biography so we only get glimpses of the theoretical environment surrounding Girard’s work, the Nietzscheanism headwinds, the boisterous dithyrambs of untruth he sailed through, now a largely spent force. On the other hand, her book abounds with amusing anecdotes. This is a life story, beginning with Girard’s Avignonais roots. Among Girard’s papers some gestures toward an autobiography have been found. But Haven rightly avers that we already have such a work in the form of his groundbreaking writings. In Deceit, Desire, and the Novel Girard argues that a literary masterpiece is the spiritual autobiography of its author, who undergoes a humbling conversion from a view of his or her compact righteousness over against what’s wrong with everybody else. To use Trevor Merrill’s resonant formula in his book on Kundera (who has acknowledged his debt to Girard), a great novel is a “satire gone wrong.” We already get an inkling of this autobiographical feature from the apocalyptic and prophetic conclusion of his very first book. We get it in thematic statements he makes to his interlocutor, Benoît Chantre, in his last book, Battling to the End, a fulsome incursion into mimetic history. But it is significant that he makes them here as elsewhere (Evolution and Conversion, When these Things Begin) in conversation. For Girard, it’s relations all the way down and every which way, and it’s not about him, it’s about truth; his originality is, if anything, his disclaimer of it, identifying the Bible as the epistemic source of his insights. While it is certainly true that we all have our own story to tell, Girard’s gift to his readers is that at a certain level, in a certain sense, it is the same story, as told to us by our biblical and literary traditions. We are born into a world of desires that do not start with us but with our models for them, good and bad, with whom we variously collaborate and compete in a common destiny to ruin or resurrection. As Bob Hamerton-Kelly concluded in a talk to historians at UCLA (he was not known for provisional utterances), “Mimesis is truth, live with it.”

Theological Anthropology and Secular Modernity

Review by Matthew Packer, Buena Vista University

and Curtis Gruenler, Hope College

James Alison and Wolfgang Palaver, eds., The Palgrave Handbook of Mimetic Theory and Religion. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017. Pages xxvii + 549.

(See volume 55, February 2018, for our review of the general introduction and parts I and II. We will complete our review with parts V, VI, and VII in volume 57.)

Part III of The Palgrave Handbook smartly begins by defining its topic of “Theological Anthropology.” Anthropology itself is widely understood aright, but theology, note James Alison and Martha Reineke in their introduction, is misconstrued by some as concerning anything vaguely religious. In fact theology is “a confessional discipline…and presupposes that God speaks or has spoken” (169). Brought together, the two disciplines concern “human being in the light of revelation.” It is a field not limited to Christian theology, but “the Christian claim that God became man in Christ makes the understanding of the human especially significant for Christian theology” (170). And Girard’s own anthropological account of Christianity raises particularly compelling questions, which several essays here explore.

In the first, “An Epistemology of Revelation,” John Ranieri carefully examines how Girard “remained on the anthropological side of the boundary [between anthropology and theology] even as his thought pointed beyond it” (174). Ranieri unpacks the problem of human reason itself being tainted by the scapegoat mechanism, and points to Girard’s conclusion that, since the Passion accounts give us the clearest exposure of scapegoating in the Bible, the Cross can be considered the key to all knowledge. Along the way we are reminded of some of that revelation’s later historical consequence. For example, as Ranieri quotes Girard, “the fact that there are no longer witch-hunts is the reason that science has been invented,” and not the other way around—the scientific spirit being “a by-product of the profound action of the Gospel text” (175, quoting The Scapegoat, 204-5).

Next are a few powerful articles on the central question of sacrifice. Mark Heim’s incisive review of “How Girard Changes the Debate,” in particular, may for many readers help unlock the puzzle concerning atonement. After critiquing the commonly practiced, “excessive focus on the ‘heavenly’ meaning of the cross,” and after cautioning against the narrow interpretations of satisfaction/substitution theories, Heim explains that Girard “dramatically reshapes the picture” by emphasizing the human importance of the Passion and the cross as scapegoating sacrifice. Heim recalls Girard’s own pithy explanation: “God Himself reuses the scapegoat mechanism, at his own expense, in order to subvert it” (181). In a helpful coda, he mentions several other theologians tackling the same question.

Similarly, Michael Hardin considers how the American Protestant reception of Girard has been challenging, given these denominations’ default paradigm of atonement—penal substitution. Mimetic theory is, Hardin notes, in many ways a “frontal challenge” to Protestant thinking insofar as it critiques economies of exchange. Hardin’s survey of Protestant Girardian engagement from 1986 to 2015 is especially helpful for its short summaries of the work of many thinkers, including Gerhard Forde, Anthony Bartlett, Heim, Charles Bellinger, Willard Swartley, Rebecca Adams, Vern Redekop, Andrew Marr, Jon Pahl, Walter Wink, James Warren, Richard Beck, and Brian McLaren. He also discusses the mimetic theory sites and organizations of Paul Neuchterlein’s Girardian Lectionary, Keith and Suzanne Ross’s Raven Foundation, and the annual Theology and Peace conference. Hardin’s own scholarship, some of it summarized here, can be read in several works, including The Jesus-Driven Life and What the Facebook?

In another, close and nuanced reading of the concept of sacrifice, James Alison shows how, following Girard’s hypothesis and the lesson of the Judgment of Solomon, we can understand Christ’s death as the One True Sacrifice—in contrast with “the falsity of all other so-called sacrifices.” In Solomon’s story, where one mother was prepared to sacrifice the child’s life and the other mother was prepared to sacrifice her claim to the child to save its life, we see a self-sacrifice that pre-figures Jesus’ self-giving up for others. On this point and Girard’s insistence on objecting to “everything sacrificial,” Alison claims, Girard never backtracked. Another, eye-opening essay here, by John Edwards, delves further into Alison’s “theological appropriation of Girard.” It too is rich in summary and insights, regarding conversion experience, the relationship among witnesses, what “making good use of a theory requires,” and the greater power of mimetic theory lying not in providing a detached understanding of atonement, but in “its capacity to help Christians uncover the experiential insight and meaning contained within the apostolic witnesses’ accounts of their encounters with the crucified and risen Jesus” (237).

Also essential reading are the contributions from Nicholas Wandinger and Petra Steinmair-Pösel. Wandinger traces the life and work of Raymund Schwager, the first theologian to develop the insights of Girard’s anthropological work for theology. We get a concise biography of Schwager, including his encounter with Girard, and the story of his Dramatic Theology and its development into a research program and school of theology primarily based at Innsbruck. For any English-readers unfamiliar with Girard’s friendship and collaboration with Schwager, Wandinger’s may be a perfect introduction. Steinmair-Pösel’s treatment of original sin and positive mimesis, as well, is vital reading. Citing Girard, she explores the idea that “original sin is the bad use of mimesis, and the mimetic mechanism is the actual consequence of this use at the collective level.” It’s a very helpful application of MT to traditional doctrines of sin and grace, one developed at a bit more length in her essay in René Girard and Creative Mimesis.

Three essays examine the relationship between Girard and other thinkers. Thomas Ryba looks at the Augustine connection, noting first Girard’s claim that three quarters of what he said can be found in Augustine. It’s a fascinating case study of influence, overturning a lot of gross generalization about imitation, and revealing gems on originality and creativity. Ryba suggests there is much yet to be ferreted out, particularly as we come to focus more, not just on historic influences, but on some of the internal mediators in Girard’s own career. Sandor Goodhart also closely examines his subject—Emmanuel Levinas and his influence on mimetic theory—most notably via the Talmudic principle, cited in Things Hidden, that “any accused person whose judges combine unanimity against him ought to be released straightaway” (242, quoting Things Hidden 444). Goodhart also examines the prophetic element common to Levinas and Girard. Ann Astell’s article on Simone Weil and Girard—an important spiritual affinity often cited, seldom truly discussed—is a genuine treat. We get to see in Weil’s own intellectual development and rivalry with her brother some striking examples of mimetic desire, carefully rendered. Here, too, for example, is Weil’s refusal to accept baptism out of the fear of the Church instilling in her a contagious “Church patriotism.”

Two other pieces are distinctive. In his exploratory essay “Embodiment and Incarnation,” Scott Cowdell pursues an original line of inquiry connecting the body-as-subject-of-sacrifice to a lot of recent materialist critical theory concerned with the body. Cowdell takes in the various speculations concerning artificial intelligence, mirror neurons, and the issues of gender and embodiment, on his way to contemplating Christians presenting their own bodies as a living sacrifice. It suggests a new avenue for “collaboration between Girardian thinkers, embodiment theoriests, and theologians.” One final essay, by Vanessa Avery, surveys mimetic theory’s implications “from the sacred to the holy,” in the world’s five major religions. Given less than a page or so on each, of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Avery does a fine job in surveying so many mimetic parallels, and the fact there might have been more space devoted to these comparisons seems to make this chapter, all the more, required reading. Those looking to explore further can turn to Palaver and Schenk’s recently published Mimetic Theory and World Religions.

Part IV, “Secularization and Modernity,” surveys one of the most multifaceted and fruitful aspects of mimetic theory. Girard’s first book offered a new diagnosis of modernity through the most distinctively modern of literary forms, the novel. His subsequent turn to older and non-Western sources led to a theory even more powerful in its potential for understanding modern secularism as an essentially religious process of desacralization. The modern economy, nation-state, science, literature, and even modern selfhood itself all can be seen as alternatives to the old sacred in ways that have been developed by other scholars, many of the most important of whom are represented in this section.

Jean-Pierre Dupuy leads off with a masterfully condensed account of where Girard, his long-time friend and colleague, fits in the tradition of thinkers, such as Durkheim and Weber, who see the origins of culture in religion and of secularization in Christianity. Dupuy then gives brief, compelling analyses of three secular ways of managing violence in the absence of the sacred: the economy, nuclear deterrence, and terrorism—all of which he has pursued in greater depth elsewhere.

The work of Dupuy and others on economics is admirably synthesized by Bernard Perret in “The Economy as the Opium of the People.” His play on Marx’s famous phrase about religion acknowledges the market’s apparent success at enabling individuals to gratify their desires peacefully and at the same time hints at its dark side. In contrast to dominant discourses that deny the economy’s inherent violence, such as mainstream theories of markets as rational, he outlines an alternative, mimetic analysis with roots as far back as Adam Smith. Perret brings the stakes into focus by concluding with the question of how to respond to the collision between ecological limits and the economic growth on which markets depend for—in a mimetic analysis—managing violence.

Turning to the other large-scale secular institution for managing violence, the nation-state, Paul Dumouchel’s chapter “The Barren Sacrifice” helpfully condenses the sweeping arguments in his book of the same title. Although states are theoretically supposed to direct all of their sanctioned violence against external enemies, they have shown a persistent tendency to make internal victims as well. These “barren sacrifices” are the starting point for Dumouchel’s analysis of how Christian practices of charity and forgiveness have led to the formation of the modern political order as well as its ongoing failure. Dumouchel’s analysis of changes in basic social and political structures is a fundamental and far-reaching extension of mimetic theory beyond Girard’s work.

Mimetic analysis of another hallmark of modernity, the rise of Western science, is the larger agenda behind David Dawson’s chapter on “The Unravelling Logic of the Salem Witch Hunt.” Taking off from Girard’s suggestion, on two pages of The Scapegoat, that the spell of magical causality accompanying the scapegoat mechanism had to be broken before science could investigate natural causes (cited also by Ranieri, as mentioned above), Dawson uses texts written during and shortly after the Salem episode to initiate a case study. The pressures placed on questions of causality by Puritan, Calvinist theology of atonement and divine sovereignty, he argues, led these authors simultaneously in opposite, natural or supernatural, directions. Lack of references here to work on Girard’s thesis about science by others underscores the great need to put it in dialogue with potentially compatible accounts of the rise of science (e.g. by Michel Serres and Bruno Latour), the development of modern theology and philosophy (e.g. Louis Dupré), and links between the two (e.g. Amos Funkenstein, John Milbank, Brad Gregory).

While secular modernity has seen literature as an alternative to religion, William Johnsen is right to observe, at the outset of his chapter, that Girard did not address himself to a general theory of literature after the manner of Northrop Frye or Erich Auerbach, though he saw their work as intersecting with his. Nonetheless, after tracing Girard on the modern novel, ancient myth and tragedy, biblical literature, and Shakespeare, Johnsen suggests that mimetic theory offers more than just a way of identifying a canon of works that embody its insights—that it brings to light literature’s general capacity to bring readers to consciousness, even of its own tendencies to indulge in mythologizing and romanticizing, and to conversion.

The inward experience of modernity gets the spotlight in the next three essays, all by Italian scholars. Paolo Diego Bubbio assembles Girard’s thoughts on “The Development of the Self” from various sources—making especially good use of his early, lesser known book Resurrection from Underground—and sketches directions taken by other MT scholars, from Girard’s important early collaborator Jean-Michel Oughourlian to his own recent work.

Emanuele Antonelli approaches “Modern Pathologies and the Displacement of the Sacred” by distilling the geometrical logic of the three kinds of mediation that configure mimetic desire, which provide a way of mapping its many pathological permutations: narcissism, masochism, etc. Under the topic of “displacements,” he briefly explores the intriguing phenomenological thesis that “intentionality at large is mimetic” (322), so that any shared sense of reality arises mimetically and is thus prone, merely in its sense of stable transcendence, to being a recurrence of the violent sacred.

One particular pathology, ressentiment, has been seen as especially important since Nietzsche diagnosed its expansion as a distinctive feature of modernity, inherited from Judeo-Christianity. Stefano Tomelleri’s “Ressentiment and the Turn to the Victim: Nietzsche, Weber, Scheler” tells the philosophical story of this insight, culminating in Girard’s mimetic analysis of ressentiment as “the interiorization of weakened vengeance” (331), which results from the exposure of sacrificial institutions. Space no doubt precludes discussion of the importance of Dostoevsky’s depiction of what he called the “underground” as an important precursor for both Nietzsche and Girard.

In the final two chapters of part IV, Wolfgang Palaver and Scott Cowdell place mimetic theory in relation to several important thinkers about secularization. Palaver concentrates on Charles Taylor, one of the most prominent philosophers to cite Girard as a major influence on his own thought and a fellow Catholic who shares Girard’s view of modernity as an outgrowth of biblical revelation. The parallels between them, as Palaver details, not only affirm their shared perspectives but also point to Taylor’s work as a bridge linking mimetic theory to other conversations. Cowdell does similar bridge-building in “Secularization Revisited: Tocqueville, Asad, Bonhoeffer, Habermas.” The similarities he traces between Girard and these four, highly diverse thinkers, too intricate for summary, are full of insight and—especially in the case of Habermas’s post-secularism—hope during an apocalyptic time.

(Cue the transition to part V, “Apocalypse, Post-Modernity, and the Return to Religion,” where we will pick up next time.)

Making Theology Relevant to the Present

Review by Petra Steinmair-Pösel

Kirchliche Pädagogische Hochschule Edith Stein

Schwager, Raymund. Gesammelte Schriften, Band 8: Kirchliche, politische und theologische Zeitgenossenschaft. Ed. Mathias Moosbrugger. Herder, 2017. Pages 560.

The last of the eight-volume collected works of Raymund Schwager shows us the Austrian theologian with Swiss roots as a politically, ecclesiologically, and theologically alert and committed contemporary, for whom theology must not reside in the academic ivory tower but has to prove itself in the lowlands of the everyday lives and struggles of individuals as well as societies and the church.

Schwager’s self-introduction as a new Jesuit professor at the University of Innsbruck—given in the late 1970s, preserved in writing in the archives, and quoted in Mathias Moosbrugger’s knowledgeable introduction to this volume—gives some insight into the importance Schwager attributes to dealing with big topical questions in their wider context. He admits that before becoming a professor, he loved working for the Jesuit magazine Orientierung, as this journalistic work gave him much freedom to address precisely those issues of his time, which seemed to him most essential and pressing; and that he was able to do so without having to enter the narrower fields of specialization. As the format of a fortnightly magazine didn’t offer enough space to deal with these questions in depth and in a more comprehensive way, however, he soon started working on his early books (Jesus-Nachfolge, Glaube der die Welt verwandelt, Brauchen wir einen Sündenbock?). These studies finally—and despite his contrary preferences—landed him in a very specialized area, a field of research which sometimes, at least in the German speaking world, is discredited for its literal narrowness: Dogmatics.

It was the encounter with the work of René Girard that, according to his own self-introduction, nevertheless opened to the Jesuit the opportunity to experience this specialization not as a form of unbearable restriction but to rather pursue Dogmatic theology in a way that keeps the windows both to other academic disciplines and to practical questions of life wide open. Volume 8 of the collected works, maybe more than any other volume, discloses to the reader the width and “groundedness” of Schwager’s theological approach.

Moosbrugger’s introduction and editorial report points out how Schwager addressed big theological issues in small formats: in numerous articles and essays, letters and contributions to anthologies. Many of them respond to topical challenges and enter a discourse with important thinkers of his time. Drawing on the rich heritage of theological thought and sharpened by his specific approach, they are designed to formulate intelligible and relevant answers to questions, problems, and challenges which greatly concerned many of his contemporaries, especially those who wanted to live as Christians in a world that no longer understood itself as Christian.

As Schwager aimed at developing a sound theological overall view on reality, his individual small publications are internally connected expressions of his comprehensive approach (either as work in progress or in its fully developed form). Moosbrugger identifies the general thesis of this approach with a hypothesis Schwager developed in his small book Für Gerechtigkeit und Frieden (For Justice and Peace), which functions as the kick-off text of this volume. This fundamental thesis could be summarized as follows: Purely political programs alone are not enough to bring about justice and peace, because they easily remain trapped within the logic of violent systems. In contrast, the biblical revelation opens a new perspective, which is genuinely present in the teachings of Jesus and becomes especially powerful in his passion, as the cross disrupts the logic of violence at the very moment when it has become most powerful. In consequence, the church is most credible when she follows Jesus in this important aspect of his teachings—when she does not let herself be drawn into the vicious circles of violence and counter-violence but follows the path of nonviolence.

This thesis of Schwager’s theology combines (1) a critical analysis of politically powerful mechanisms of violence with (2) the call for an emblematic stance of the church against these powers in her life and her teachings, a stance which is (3) grounded in the biblical revelation and has to be developed from there.

Apart from Für Gerechtigkeit und Frieden, volume 8 of the collected works assembles twenty-two shorter texts in three sections: Ecclesial contemporariness, political contemporariness, and theological contemporariness. Within each section, the texts, which were written/published between the early 1970s and the early 2000s, are arranged chronologically, thus spanning a period of about 30 years. Moreover, the volume includes the theologically exciting correspondence between Schwager and his compatriot and co-Jesuit Hans Urs von Balthasar. All the texts are provided with an excellent corpus of editorial remarks which contextualize them and help to better understand their respective temporal and factual background.

The first section, ecclesial contemporariness, includes articles on the experiences with the Swiss synod of 1972, the conditions of unity between the Orthodox and the Catholic churches, the understanding of the human consciousness of Jesus in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, a dramatic concept for the encounter of religions, and reflections on the interreligious prayer meeting in Assisi (2002) and the fate of Jerusalem.

The articles of section two, political contemporariness, critically address the just war theory, elaborate on a Vatican document on disarmament from 1976, define religion as the basis of an ethic of nonviolence, deal with the relationship between violence and religion, and call for Christian-Islamic dialogue in the wake of 09/11.

Section three, theological contemporariness, is the most extensive one, discussing, among others, highly disputed topics such as: Hans Küng’s Infallible?, violence and sacrifice, the wrath of God, mimesis and freedom, the empty tomb in contemporary theology, biblical texts as mixed texts, dramatic theology as a research program, and the relationship between theology and historical science. The correspondence between Schwager and von Balthasar concludes this part, and a final epilogue by Józef Niewiadomski characterizes Schwager’s approach as theology for the dramatic era of religious pluralism.

While this volume comprises many thought-provoking texts by Raymund Schwager, as a personal favorite I want to mention one that has previously been unpublished. It is a groundbreaking article on the ordination of women in the Catholic Church: one by one Schwager addresses all the arguments that are usually cited against female ordination to priesthood. And one by one he unhinges them, finally coming to the conclusion that Pope John Paul II’s position in Ordinatio Sacerdotalis is not based on a broad ecclesial consensus and will remain a permanent seed of contention unless it is properly reviewed and altered. If for no other reason, volume 8 of the collected works is worth reading because of this article, which reveals Schwager’s critical loyalty with his Church in its highest form. Maybe it’s best defined as “dramatic.”