Contents

Letter from the President, Jeremiah Alberg

Editor’s Column, Curtis Gruenler

COV&R Annual Meeting 2019 at Innsbruck

COV&R Sessions at the American Academy of Religion, Grant Kaplan

Evolution of Desire: A Life Ascending, Kevin L. Hughes

History and Story: Reflections on Evolution of Desire, Martha Reineke,

Wolfgang Palaver 60th Birthday Celebration, Wilhelm Guggenberger

Letter from… Bogota, Roberto Solarte

Paul Dumouchel, The Barren Sacrifice: An Essay on Political Violence, reviewed by Joel Hodge

Emily Swan and Ken Wilson, Solus Jesus: A Theology of Resistance, reviewed by Curtis Gruenler

Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri & Hostiles, Luke Nelson

Letter from the President

Jeremiah Alberg

International Christian University

Here in Tokyo, autumn has come in earnest. The air is chill, the leaves are turning, the sky is a lovely blue. My house grows cold in the night and a kerosene stove gradually spreads a welcome warmth in the early hours. In Japan, as in some other countries, late November is a time of thanksgiving. I have a number of things to be grateful for, but right now I am particularly grateful for being able to teach a course here called “Introduction to Christianity.” It is the course that everyone who graduates from this school is required to take. Some students take it right away in their first semester, some put off until right before graduation. The background the students bring to it is incredibly varied: from fundamentalist Christians to students who have literally never read a word of the Bible. The main part of the course is reading Girard’s The Scapegoat.

Students have a variety of assignments but also have what I call, “The Artistic Option.” I started this two years ago when the Raven Foundation sponsored a contest for undergraduate students to submit some artistic project that gave expression to mimetic theory. Generally, out of about 100 students, 10 will chose this path. Our terms are short here and so they often begin to panic around the fifth week as we are only half way through the text and they still do not feel like they have any grasp on the overall theory. But somehow they manage to pull it all together and they have produced some wonderful pieces.

Beyond the art itself, the other students’ reaction to the art is also of interest. They are often amazed at the art produced and feel like they have gotten a new understanding of the whole class through their peers’ projects. I would like to share two of these projects with you. One is a photo essay titled “Traversing into the Mechanism” by Mr. Joshu Majima. It includes his artistic statement.

Second is a ballet created by one of the students, Ms. Manaka Tomoda. Her explanation is the following:

The Statement of the Artistic Project “Good Bye Mimesis”

This project is a short ballet piece choreographed and performed by Manaka Tomoda using a music piece “Fantasia on Greensleeves” composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams. It reflects what I have learnt from Introduction to Christianity about “mimetic desire.” We suffer and have conflicts because of mimesis. It seems to be impossible to stop imitating what others want. However, understanding the fact that many uncomfortableness come from mimetic desire can potentially make people feel better as it releases them from the unknown hostile emotion against others.

The dancer is suffering from the world full of ugliness. She does not know what she wants and how to want something by her own desire but just imitates others. She knows only her world, but she instinctively feels that there should be a way to live better with less jealous and conflicts. This is why a series movements is always repeated in the first part of this ballet as the representation of mimesis; the right side version is always followed by the left side one as the representation of mimesis.

Then she hears something. Carefully getting closer with a little hesitation, she gets a message. It says “You suffer because you imitate others. It is fine to want what others want. However, you have to know that you are controlled by the mimetic desire. When you understand the power of mimesis and are able to let all the troubles caused by mimesis go, you feel better and so does your life. Be brave enough to be different from others. And spread this message to people around you”. She accepts the message and starts telling others. This happens in the middle part of this ballet piece. This part has no choreography as it is an impromptu. It simply reflects my impression to express this sensitive part, or receiving message, realising how powerful Mimesis is, and telling people the message.

Then she is free from mimesis, or at least free from unconsciously being controlled by Mimesis. She does not repeat the same movements anymore as she knows she does not have to. She smiles because she simply enjoys dancing. Comparing the last part to the first one, it is obvious that the message has really changed her. She says “Good bye mimesis”, kissing to the direction of the message.

Editor’s Column

Curtis Gruenler

Hope College

We delayed this issue of the Bulletin past its November publication target to report on COV&R’s sessions at the meeting of the American Academy of Religion. In addition to an overall report, you’ll find papers about Cynthia Haven’s Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard given by Kevin Hughes and Martha Reineke as well as a response by Haven herself.

Let me also draw your attention to Robin Lathangue’s long and insightful review of the volume Mimetic Theory and World Religions. Such an extensive review (like our three-part review of the Palgrave Handbook of Mimetic Theory and Religion earlier this year) seems justified for this landmark treatment of concerns that have been central to COV&R since its founding and have only become more important as mimetic theory reaches a broader audience.

This issue also features our first film review, which begins with some thoughts about what kind of a review might suit the Bulletin: the same size as a typical film review (rather than an academic article), but unafraid of spoilers and willing to discuss the full arc of a plot, especially the final act, where mimetic insights are more likely to be revealed. We would be glad to have others. If you are interested in writing one, please contact me.

Complete videos of the keynote lectures from last summer’s annual meeting in Denver are now available on the COV&R website under the Annual Meeting tab and on COV&R’s new YouTube channel. In addition, an interview of keynote speaker Jack Miles about his new book God in the Qur’an is available on the Raven Foundation site.

The Raven Foundation publishes articles written by students and professors in its Your Voice section. They would love to receive articles from COV&R members and their students.

“An invitation site for creative people who seek to interpret their world in fiction or drama that sees what René saw”: that’s how John Young, one of the authors behind the new website describes its vision. “It is not enough to get a new pair of glasses: one must then passionately attack what I call notseeing, the willful refusal to see injustice and scapegoating in real time, in one’s own space.”

Chair 37 of the French Academy, vacant since René Girard’s passing three years ago, has now been filled by medievalist Michel Zink, whose customary tribute to his predecessor was, as Cynthia Haven wrote on her blog, “highly praised.”

Finally, I had the opportunity to attend a wonderful lecture by Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, on prayer in Shakespeare at the University of Notre Dame on November 26. Though Williams did not mention Girard or mimetic anything, his lecture would make a fitting coda to Girard’s A Theater of Envy. He began and ended with the epilogue to Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest, in which the magician Prospero, laying down his powers, puts himself at the mercy of his audience: “my ending is despair / Unless I be relieved by prayer.” In some earlier Shakespeare plays, those who pray—Henry V, Claudius in Hamlet, and Antonio in Measure for Measure—find themselves frozen and isolated by inability to make adequate repentance and restitution. Prospero, turning to the audience for help and inviting their gesture of putting their hands together to mean more than applause, briefly transforms the theater into an instance of bearing one another’s burdens and setting each other—characters, actors, playwright, audience members—free. While A Theater of Envy shows how Shakespeare’s insight into mimetic dynamics makes him alert to how theater always teeters on the brink of a sacrificial catharsis, Williams pointed to how Shakespeare’s farewell to the stage models a liberating interdividuality. An article version is forthcoming in the journal Religion & Literature.

Forthcoming Events

2019 Annual Meeting

Innsbruck, Austria, July 10-13, 2019

“Imagining the Other:

Theo-political Challenges in an Age of Migration”

We live in an age of migration—often forced—with its special challenges. How we imagine “the other” is a decisive element in the (theo-)politics of exclusion and desire that feed on these challenges. Aware that imagination is a mimetic process, COV&R’s 2019 annual meeting wants to address these challenges by trying to illumine different aspects of this complex entanglement, asking whom or what we mean by “the other”: the stranger and migrant, the brother or sister, nature that envelopes or defies us, the transcendent Other to whom religions refer, the other sex or gender….

Scheduled subsections will include:

- Migration, ecology, and economic justice

- Exclusion and the transcendent Other

- Imagining the other: media coverage of migrants and refugees

- How do Europeans view the “others”?

The theme, “Imagining the Other,” also widens the conference’s range of topics beyond migration to other fields of interest for COV&R members.

The keynote address will be delivered by Cardinal Peter Turkson, formerly President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, now Prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development.

The keynote address will be delivered by Cardinal Peter Turkson, formerly President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, now Prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development.

COV&R 2019 will coincide with the 350th jubilee of the University of Innsbruck, western Austria’s largest institution of research, with 28,000 students and 4,500 staff. Innsbruck is a city of 132,000 located at an elevation of 574 meters (1,722 feet) in the Inn River valley surrounded by mountains of the Tyrolian Alps extending up to 2,300 meters (7,000 feet) that can be reached by a cable car.

The conference host is the university’s Jesuit-affiliated Faculty of Catholic Theology, which enrolls about 800 students, including about 40 Ph.D. students from around the world. It is famous as the academic home of theologians Josef Jungmann, Hugo and Karl Rahner, and Raymund Schwager. Schwager’s legacy of collaboration with René Girard lives on in an active research program that has included many COV&R members, including conference organizer Nikolaus Wandiger.

The conference’s cultural program on Saturday, July 13, will feature a 45-minute bus ride to the village of Stams, site of a Cistercian Abbey founded in 1273, where the tour will include a special exhibition about Emperor Maximilian I, who tried to negotiate peace with the Turks. The tour will be followed by a concert of the Regensburg Cathedral Choir and dinner in Stams.

Travel and accomodations: The closest international airport is in Munich, a 2-hour train ride away. Innsbruck’s own airport has good connections to international hubs in Frankfurt and Vienna. Attendees will arrange their own accommodations at hotels near the conference site in the city center or at a limited number of rooms in ecclesiastical guest houses. Further information will be posted on the conference web site.

Conference Reports

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion

Grant Kaplan

St. Louis University

Registered as a Related Scholarly Organization, COV&R continued to host programming at the world’s largest meeting of religion scholars: the American Academy of Religion and Society of Biblical Literature, which about 12,000 people attend. This year, COV&R hosted two sessions in Denver.

The first, a panel dedicated to Cynthia Haven’s Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, took place on Saturday November 17th. Three panelists—Kevin Hughes (Villanova University), Martha Reineke (University of Northern Iowa) and Trevor Merrill (California Institute of Technology and the Thiel Foundation) reflected on the book. COV&R was deeply honored that Cynthia Haven accepted our invitation to attend the session and generously offered a response. A lively question and answer followed, which included several helpful interventions and anecdotes from Sandor Goodhart.

Evolution of Desire has been widely reviewed. The COV&R Facebook page contains links to many of these reviews. The AAR session presentations differed from these reviews in that each presentation melded elements of a book review with critical reflections by a representative scholar of mimetic theory. Each speaker sought a constructive engagement with Evolution of Desire and its author in ways that advanced critical reflection on mimetic theory. Since most COV&R members were not able to attend the AAR meeting, we are pleased to publish below a sampling of the session with two of the papers as well as Cynthia Haven’s response.

COV&R’s second session, on the topic of mimetic theory and Christian spirituality, took place the next morning, the 18th of November. It consisted of three papers: (1) James Alison (Madrid, Spain), “Interdividuals, Individuals and Fragmented Selves: How Can Mimetic Theory Help Us Understand ‘Huiothesia’?” (2) Randy Rosenberg (Saint Louis University), “The Spiritual Texture of Trauma: Mimetic Desire, Psychic Conversion, and the Healing of the Damaged Self”; (3) Brian Robinette (Boston College), “Mimesis, Meditation, and the Art of Creative Renunciation.” As with the Saturday session, all of the panelists brought their “A” game. Robust discussion followed. At a reception on Sunday night, an acquaintance said that people had been talking about the panel all day as “the best panel at the AAR.” About fifty people attended, which put us at capacity.

Grant Kaplan convened both sessions. About twelve people stayed for the business meeting and proposed various ideas. We will set the program for next year (San Diego, November 23–26) in the spring. If you have ideas, please send them to Grant.

Evolution of Desire: A Life Ascending

Kevin L. Hughes

Villanova University

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

ché la diritta via era smarrita.

We will all recognize these immortal first words from the Divine Comedy. We may recall that Dante sets his great poem in the year 1300, when he himself was 35 years old, “in the middle of this our life.” It was at this moment, he says, that he awoke. He had been sleepwalking through his life, he tells us, and then this moment brought him back. It set before him a long journey; he would write the Divine Comedy for the rest of his life, finishing the Paradiso just before his death. Prior to this moment, we may know, Dante seems to have abandoned writing. At the end of La vita nuova, in 1292, Dante pledges that he will no longer write about Beatrice until he is capable of something never seen before. But in fact, Dante doesn’t write anything—or not anything that we still have—until after this moment, nel mezzo di cammin di nostra vita, in 1300. But after this, he writes one of the greatest poems in Western literature.

René Girard, too, faced a moment, in the middle of this our life, at age 35, on the train between Baltimore and Philadelphia, during which he awakened to a whole new way of seeing. The conversion, first of intellect, then of will, in the winter of 1958-59, so carefully painted for us in Cynthia Haven’s book, is the generative fact of the rest of his life’s work. Girard tells Haven, “My intuition comes first, and it leads me toward vivid examples, or burns them into my memory when I happen upon them by chance. This has led to misunderstanding, even condemnation among ‘specialists’” (119). From Girard’s point of view, this moment, this insight, which came all at once, is gradually unfolded in a life’s work that provides the occasion for our gathering here today. Without this moment, nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita, Girard’s career may have been entirely ordinary.

History and Story: Reflections on Evolution of Desire

Martha Reineke

University of Northern Iowa

Cynthia Haven’s biography of Girard is a substantive contribution to the literature with broad potential to inform the work of the next generation of Girard scholars. Wonderfully, Evolution of Desire has been widely reviewed, introducing Girard to persons previously unfamiliar with his work and sustaining public attention that began at the time of his death. More important, the book enables readers to see in the corpus of Girard’s work prescient commentary on current issues. As a consequence, Evolution of Desire does not invite engagement; it demands it. And for this, all of us can be grateful to Haven.

In Haven’s interview with Bret McCabe about the biography, she accounts not only for Girard’s significance as a scholar but also for why Evolution of Desire is an important contribution to Girardian literature. Haven says of Girard’s writing:

It invites you to change your life. Not in the sense of becoming a camp follower or a professional “Girardian,” but rather encouraging awareness of how we scapegoat others, how easily we join crowds, and how we hunger for the wrong things for the wrong reasons. These are at once the lineaments of human history and the contours of our personal stories as well [emphasis added].

Cynthia Haven Responds

Several years ago, Bill Johnsen invited me to develop a book idea about René Girard for Michigan State University Press. After some thought, I pointed out that nothing had woven together the work and the life, with the aim of creating a “good read.” Martie didn’t want it to be a page-turner, well… I kind of did. But not that only. I knew that ordinary, educated people who wouldn’t ever pick up a discussion of René’s theories, just might read about his work if it was embedded in a narrative, the story of a man. And it’s a good story, a story with a happy ending, perhaps even a triumphant one.

To do that I had to explain why his life mattered, and why his theories matter today. I would have to take a body of ideas, and make these ideas felt. That wasn’t easy, but worthwhile things usually aren’t.

The biography business is ruthless. When writing a book like this, you have to be prepared for friendships to break, even with people you care about. You have to take risks, and do what’s best for the book. If I were trying to please René or Martha Girard, or any of the other cast of characters, I knew I wouldn’t write anything worth reading.

Wolfgang Palaver 60th Birthday Celebration

Wilhelm Guggenberger

Wolfgang Palaver celebrated his 60th birthday on 27 September 2018. To introduce him in the context of COV&R seems absolutely superfluous as he is not only a long-term member and former executive secretary and president of our association, but always was and still is an inexhaustible source of inspiration for many of us. By this he—the disciple of Raymund Schwager and intimate friend of Martha and René Girard—has helped to shape the development of COV&R remarkably to this day.

Because Wolfgang was using a sabbatical to participate in a research program about violence and religion at the Center of Theological Inquiry in Princeton, the official celebration of his birthday in Innsbruck could only take place on the 5th of October. Part of this celebration at the Catholic Theological School was a solemn tribute including addresses by the principal of the university, the dean of the school, the representative of the diocese, and members of Pax Christi as well as a lecture given by Prof. Hansjörg Schmid from the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. Schmid’s topic was the development of interreligious social ethics. Even if this topic signifies a central concern of Wolfgang, we were convinced in advance that the traditional form of such an academic celebration could not be adequate to this particular birthday boy.

Therefore the head of the department of Systematic Theology, Roman Siebenrock, decided to organize something he called a laboratory. What does that mean? A laboratory is where scientific work takes place in a collaborative style, where new ideas are tested and established theses are challenged to gain sounder knowledge. It was exactly this that a group of colleagues from the University of Innsbruck and some guests tried to do together with Wolfgang for a day. The established theses were given in texts published by Palaver according to five decisive topics of his scientific work: violence and religion, capitalism as religion, democracy and populism, non-violence and ethics of peace, and the connection or tension respectively between political philosophy and political theology. To each of these topics responses were given by colleagues who have been accompanying Wolfgang for a considerable time. Some of these impulses were pretty critical even if appreciating the work of the author. This was quite intended because we did not only want to honor our colleague and friend but do together with him what he likes to do most: discussing challenging questions. Of course Wolfgang was given plenty of time to respond and to unfold his thoughts, which again showed that scientific discussion to him is no l’art pour l’art, but rather becomes meaningless when it is not understood in a way to serve the development of better life.

It is not possible to record the vivid discourse which arose that day. I only want to mention a few moments interesting to mimetic thinking in general. One topic occurring time and again is the relationship of religions. In our context it was triggered by a discussion about Hölderlin, who plays an important role in Girard’s Achever Clausewitz. The biography of the poet seems less interesting to Palaver than the close kinship of Greek pagan deities and Jesus Christ depicted in Hölderlin’s hymns. This observation is a perfect starting-point to more precisely discuss the complex relationship between archaic religions and biblical revelation in Girard. There cannot be an absolute contradiction; otherwise the longing for peace even recognizable in the violence of the scapegoat-mechanism could not be understood in a convincing way. This opens up the Girardian approach much more to an interreligious dimension than does the view that sees a stark opposition between the revelation of the gospel and archaic or non-biblical religions.

Another, closely related discussion is whether the anthropology of the mimetic approach is merely pessimistic or not. Is the center of our considerations the human being created good by God or is it the corrupted sinner totally prone to violence? To me this seems to be a very important question that makes it important not to emphasize Augustinian thinking in Christianity too much. In this context theological thinking becomes really influential according to the assessment of political, juridical, and also economical institutions. One part of this discourse is the enigmatic biblical concept of the katechon. To Palaver, and to me as well, this concept seems to be quite helpful to integrate real politics on the one hand and the expectation of the kingdom of God on the other without becoming either merely pragmatic or escapist.

Last I want to mention our discussion about kenosis, which during recent years has become more and more a crucial point in Wolfgang’s thinking and, more than this, in his spiritual life. Jesus Christ is the humble servant of God. In him God encounters with us giving up each kind of compelling power. Thus our image of God is shaped by the idea of kenosis, which sometimes is depicted in the way of a withdrawal of God who has to make room for human existence. Even if such formulations are part of several spiritual traditions, they could be misunderstood in a way that induces the destructive imagination of rivalry between God and man as if humans could only exist in the absence of God.

I am sure our discussions will go on, especially when Wolfgang has come back to our faculty from Princeton with a lot of new ideas in his head and a lot of new literature in his data bank. To all of you a possibility to participate in this discussion may be the COV&R Meeting in Innsbruck next July.

Letter from… Bogotá

Roberto Solarte

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana

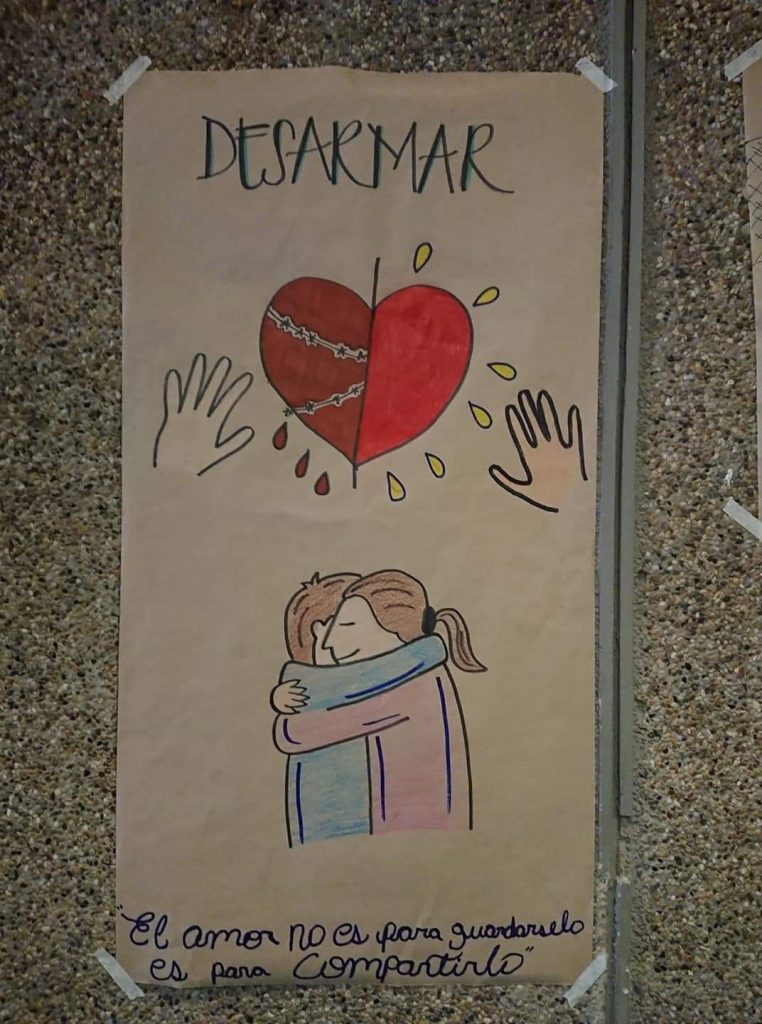

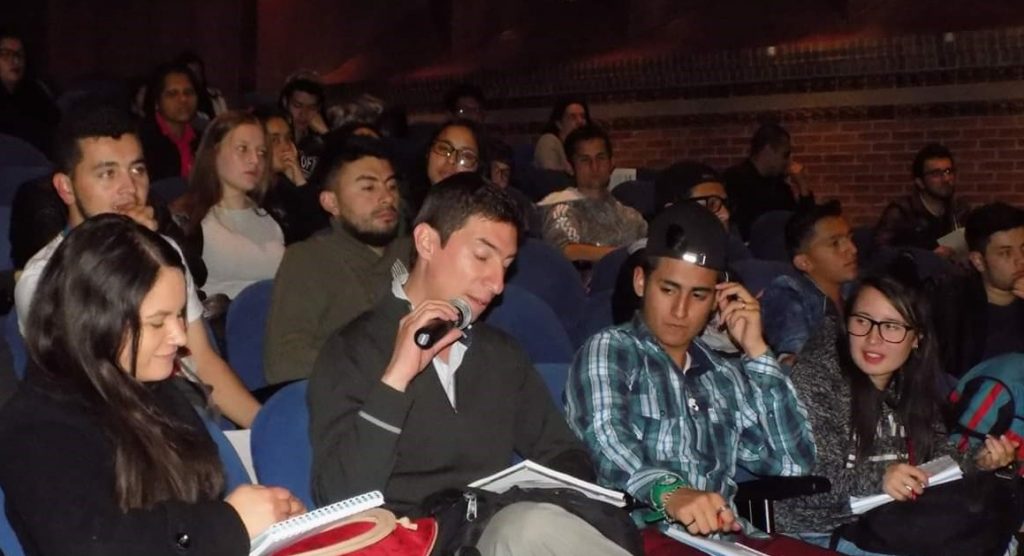

As a research group in philosophy and theology from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, we study the relations between the former expressions of “Liberation Christianism” and the construction of peace and reconciliation in Colombia nowadays. We have also designed a non-formal educational process oriented towards the youth; it´s called Diplomate Course in Juvenile Participation for Peace and Reconciliation. For that educational process, we work in cooperation with the social program from the Faculty of Engineering, the Fe y Alegría Foundation, Bogotá´s Town Hall, and many volunteers.

As a research group in philosophy and theology from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, we study the relations between the former expressions of “Liberation Christianism” and the construction of peace and reconciliation in Colombia nowadays. We have also designed a non-formal educational process oriented towards the youth; it´s called Diplomate Course in Juvenile Participation for Peace and Reconciliation. For that educational process, we work in cooperation with the social program from the Faculty of Engineering, the Fe y Alegría Foundation, Bogotá´s Town Hall, and many volunteers.

In addition to recollecting experiences from the ecclesial communities in their popular ground, we have tried to translate several elements of the mimetic theory into popular education. For this, we promote positive models of resistance to the violence and reconciliation in the communities in which we have worked. We believe that in this way we promote creative ways of peace building. As this is not enough, we have focused this process in a spirituality of nonviolence that makes possible the growth of the communities and social change renouncing violence.

In addition to recollecting experiences from the ecclesial communities in their popular ground, we have tried to translate several elements of the mimetic theory into popular education. For this, we promote positive models of resistance to the violence and reconciliation in the communities in which we have worked. We believe that in this way we promote creative ways of peace building. As this is not enough, we have focused this process in a spirituality of nonviolence that makes possible the growth of the communities and social change renouncing violence.

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the book review editor, Matthew Packer.

Hope and Grief

Robin Lathangue

Sacred Heart College, Peterborough, Ontario

Wolfgang Palaver and Richard Schenk, eds., Mimetic Theory and World Religions, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2018. Pages xxii+456.

Wolfgang Palaver and Richard Schenk, eds., Mimetic Theory and World Religions, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2018. Pages xxii+456.

René Girard’s theories are conceptual levers useful for prying apart lids on the jars of some beautifully difficult questions—not least, those about academic nomenclature. Fellow Académie Française immortel Michel Serres called Girard “the new Darwin of the human sciences,” but is Girard’s oeuvre best characterized as scientific, humanist, literary, psychological, theological, anthropological, or none, some combination, or all of these?

What makes this anthology a challenge to review is that the puncture-resistant boundaries between cognate disciplines are rendered permeable, even porous, by the capaciousness of carefully applied Girardian analysis. The resulting commons is an intellectual, sometimes scientific, at times spiritual, certainly humanistic going concern, and no place for the faint of heart.

The Ties that Bound

Joel Hodge

Australian Catholic University

Paul Dumouchel, The Barren Sacrifice: An Essay on Political Violence, Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2015. Translated from the French Le sacrifice inutile: Essai sur violence politique, Flammarion/ARM, 2011, by Mary Baker. 242 pages.

Paul Dumouchel, The Barren Sacrifice: An Essay on Political Violence, Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2015. Translated from the French Le sacrifice inutile: Essai sur violence politique, Flammarion/ARM, 2011, by Mary Baker. 242 pages.

Paul Dumouchel’s The Barren Sacrifice provides a rich and insightful analysis of human societies, their changes over time, and the development of the modern state and political violence. The richness of this book is built on a sophisticated engagement with and application of mimetic theory, which is integrated with important studies as well as historical and philosophical works. It is an important contribution to the “mimetic history” project that René Girard called for.

Dumouchel’s “essay on political violence” (the subtitle) challenges the notion that the state is a neutral “protector.” The state claims a monopoly of physical violence in order to protect its citizens from external enemies. Rather than a supernatural justification, the state is said to rely on “rational” and “secular” justification. Yet, as Dumouchel points out, states politically legitimise themselves because they possess the means to do so, and in doing so, define what is legitimate and illegitimate violence. Importantly, Dumouchel demonstrates that the state defines cultural difference, which the sacred had done for archaic societies. The state has appropriated the role and function of the sacred (who as the victim-god regulated violence through ritual and prohibition).

Scapegoaters Anonymous

Curtis Gruenler

Hope College

Emily Swan and Ken Wilson, Solus Jesus: A Theology of Resistance. Canton, MI: Read the Spirit, 2018. Pages 383.

Solus Jesus addresses, first and foremost, members of Christian traditions committed to the Reformation principle of sola Scriptura, the Bible alone as the source of final authority—and especially those who have found this principle inadequate to resolve controversies such as LGBTQ+ inclusion. Its alternative, focused on experience of the living Jesus as “our rabbi still,” will be welcome to a broader audience because of how the authors, co-pastors of Blue Ocean Faith Ann Arbor, answer “the inevitable question, ‘Which Jesus?’” Their answer, “the God of victims—Jesus revealed through the lens of scapegoat theory,” puts the thought of René Girard at the center of their “theology of resistance.” From this center, and drawing on years of pastoral and missionary experience as well as wide reading, Swan and Wilson develop a compelling vision of Christian life and community that combines Girardian anthropological and scriptural insights with a confident expectation of the work of the Holy Spirit abroad in the world.

They present this vision in three parts: first, the shift from sola Scriptura to solus Jesus; second, an introduction to mimetic theory and its reading of Scripture; and third, proposals for “a new way forward” in theology, church life, spiritual practice, and relations with adherents of other religions. Aside from an introduction and afterword, the chapters are written by either Swan or Wilson, which allows each, in their refreshingly distinctive voices, to bear witness to his or her own experience and thus illustrate the approach to authority they propose.

Film Review

Genres at War with Themselves

Luke Nelson

M.F.A. USC School of Cinema

Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri, directed by Martin McDonagh, 2017. Hostiles, directed by Scott Cooper, 2017.

From the first day of film school, I was taught the most important lesson is to inspire empathy in the audience. Later that year, 9-11 happened. I began to question the “empathy industry.” Like many in that time, I reached for Noam Chomsky, and then for Slavoj Zizek, two masters of the narrative duel. A few years later, a good friend recommended René Girard. Here was not only a revolutionary thinker, but in COV&R, a group of academics and writers devoted to the interdisciplinary callings of mimetic theory. Like many of us in COV&R, I am sure, I was enthralled with Girard’s words in the introduction to Battling to the End, “They cannot do without a cruel god…. They have no sense of humor.” I preferred to read “they” as “we” in the movie audience.

With some encouragement from friends, I am sharing two movie reviews with COV&R that are a year too late, but which also serve as proposals for what a mimetic movie review can be. I think a mimetic review should maintain the same length and readability of a movie review, but should diverge from shallow marketing in order to boldly discuss the third act. That sacrificial space of “what happens,” with all its emotion and blood, must confront a creativity of truth-telling against the status quo of violence, yet remain immediately readable. If “spoilers” are highly valued, then a mimetic review merely (radically?) seeks an audience in the aftermath of the movie.

Each genre, within the rules of its game, represents an escalation to an extreme. Maybe a mimetic movie review should be a response to the third act—a punchline that confronts the games of so many cruel gods with a deeper sense of humor.

Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri is not an ideal movie because the tone challenges genre convention, it follows the arcs of two characters rather than one, and it gets kind of allegorical about violence. An authenticity of human experience is usually the sacrifice for these oversteps. But writer-director Martin McDonagh strikes a shaky balance between the small-town familiarity of neighbors lifting each other up in suffering, and a prankster vengeance that escalates to permanent disfigurement. The shaky balance itself, like a fiddler on a roof, is authentic to a small town. The movie has stars, but the story dares to digress into the sociality of the community, anywhere (“Ebbing” is fictional). Highly opioniated critics such as Armond White get Three Billboards totally wrong if they use “archetype” dismissively. (To wit, we need more movie critics that fit a culture-critic archetype, like Armond White. But we don’t always need more Armond White.)

Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri is not an ideal movie because the tone challenges genre convention, it follows the arcs of two characters rather than one, and it gets kind of allegorical about violence. An authenticity of human experience is usually the sacrifice for these oversteps. But writer-director Martin McDonagh strikes a shaky balance between the small-town familiarity of neighbors lifting each other up in suffering, and a prankster vengeance that escalates to permanent disfigurement. The shaky balance itself, like a fiddler on a roof, is authentic to a small town. The movie has stars, but the story dares to digress into the sociality of the community, anywhere (“Ebbing” is fictional). Highly opioniated critics such as Armond White get Three Billboards totally wrong if they use “archetype” dismissively. (To wit, we need more movie critics that fit a culture-critic archetype, like Armond White. But we don’t always need more Armond White.)

Three Billboards is also a masterful crime story that escalates to implicate everyone and no one. “Raped while dying. And still no arrests? How come Chief Willoughby?” The open-ended result is a fruition of its complex tone. This investigation in criminal grief keeps us laughing, which is the only satisfaction we will get. In a crime thriller, we want more bloody satisfaction, more justice. In a comedy, we want more escape from anxious conflict, more romance.

Would a grieving mother have this much drive to mess with people? Frances McDormand’s Oscar-winning Mildred Hayes shows a range only a few people have, and not many directors dare attempt. Knowing a sliver of what is right and crossing an entire world of boundaries to prove it is standard masculine-hero crap. But the best scenes show her pushing her agenda while the men around her break under the scrutiny and strain. A few times, she suddenly turns into a nurturer. The joke is on the men who cave in and can barely do their job. Her son and ex-husband let her know her anger is totally out of line. Yet, it is her momma-bear archetype that is secretly charged with keeping order in the small towns, anywhere.

In a flashback to that fateful day, the last words exchanged between mother and daughter were a kind of mutual warning of the threshold of adulthood and wilderness: young, rebellious women are destined to be victims of violent strangers. The cold nastiness of Mildred’s grief comes from a deep guilt, because she echoed these reckless threats of exasperated parenting.

In the middle of the story, Mildred’s scapegoat Sheriff Willoughby (Harrelson) ends his life to shield his family from a slow death to pancreatic cancer. People blame Mildred and her billboards. But Willoughby leaves behind Three Letters of Ebbing, Missouri: for his wife, for Mildred, and for his racist deputy, Jason Dixon (Sam Rockwell, also Oscar-winning for best supporting).

As the town’s caveman, Dixon looked up to Sheriff Willoughby like a god (despite, nay, because of, Willoughby’s constant scolding.) But his letter intends to inspire conversion:

“…And I know you’re going to wince when I say this. But what you need to become a detective, is love. Because through love comes calm. And through calm comes thought. And you need thought to detect stuff sometimes, Jason. It’s kind of all you need. You definitely don’t need a gun. And you definitely don’t need hate. Hate never solved nothin’. But calm did. And thought did. Try it…”

The three billboards asked, “Why, god?” but the god only has fatherly advice for the warring parties.

Dixon’s gumshoe detective effort against a creep that fits the profile is also a self-sacrificial reconciliation with Mildred, but the DNA gives no match. The hope in nailing the guy that did it turns into a vengeance plot shared between them to kill the guy that didn’t do it, because he surely did something, to some girl, somewhere.

This is a stroke of genius in Three Billboards. It is not a breaking of the fourth wall, but the audience’s need for that ritualistic third act of violent justice overcomes the two reconciled detectives—overcomes the logic of detective work itself—and returns them to their heroic fantasies as executioners of justice.

Mildred and Dixon quietly check the titillation of the audience before the road trip of blood: they both say slow goodbyes to their sleeping loved ones, as if they know that crossing this final threshold will not bring a glorious Return of the Hero. But the journey cannot be completed in the time we have, and is thrown back into the audience’s imagination: on the road, they confess their doubts about killing, and decide to figure it out on the way…

&

Scott Cooper’s and Christian Bale’s Hostiles succeeds where the comic allegory of Three Billboards might be seen to “fail,” in the sober meditation on race war and the human costs of violence. But Hostiles suffers a near total failure in a meaningless third act, enslaved to the genre rules of shoot-outs.

Scott Cooper’s and Christian Bale’s Hostiles succeeds where the comic allegory of Three Billboards might be seen to “fail,” in the sober meditation on race war and the human costs of violence. But Hostiles suffers a near total failure in a meaningless third act, enslaved to the genre rules of shoot-outs.

A fatigue of war within our borders weighs heavily on Hostiles. Since 9-11, the forgotten wars on terrorism and the gun violence in civil society is slowly dragging our nation into a descent of constantly feeling war-torn. Christian Bale’s Captain Joe Blocker fought the Indians at Wounded Knee, but due to changing political climate, and President’s orders, must escort an old Cheyenne war enemy, Chief Yellowhawk (Wes Studi) and his family into his traditional burial grounds of Montana.

Are there two filmmakers at war in Hostiles? Sparked by the D. H. Lawrence quote at the fade-in, “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted,” the bookends of the movie are intentional in their vicious mirroring of native savagery and then white savagery. But this is a total betrayal of the inner evolution toward mercy and forgiveness. The middle of Hostiles is the Melting of Joe Blocker.

On the journey with their old war skeletons, Blocker’s detail meets a new widow (Rosamund Pike) talking to her family of corpses in her burned-out home, victims of a band of Comanche, who will threaten our group again. There is a band of kidnapping and rapist fur-trappers, a military prisoner (Ben Foster) who fought alongside the Lieutenant and his friend Tommy Metz (Rory Cochrane), reminding them of the thin line between doing a military “job” and racist bloodlust. Sometimes the episodes distract with unnecessary violence, but it does not seem to threaten the slower burns of mutual respect that develops between the Cheyenne and the whites, and the confessional mirrors into the bipolar insanity of war offered by Cochrane’s depressive and Foster’s manic performances.

In an interview with Matthew Lickona of the San Diego Reader, Bale’s research for another project in 2005 brought him to a discovery of the military’s active taboo on PTSD. He found the reporting on military suicides in the Army Times to be far better than the conventional media’s, so Bale visited a Marine recon team in Camp Pendleton, who responded, “There’s no such thing,” when asked about PTSD. “What I found was then when you spoke with them as a group, they said it didn’t exist, because they do not want to be the one who shows vulnerability that then becomes infectious.” Bale’s Joe Blocker gruffly dismisses “the melancholia” with the same words to his Sergeant and friend Tommy, after he tells Blocker that the army stripped him of his guns, and he feels like he is “near the end of his sojourn.“

But the Western about remembering war trauma forgot itself. How can a narrative so fatigued with war, about a journey to reach burial grounds, suddenly raise their guns for a stand-off over a property dispute? To be fair, the answer might be “empathy” for the Cheyenne tradition, to stand and fight with them. At the same time, the third act seems to have a total ignorance of its own lingering despair in violent conflict.

Bale’s Lieutenant Blocker was suddenly not the same man that lived through the first 90% of the story. The hurried falseness of the final shoot-out is infuriating, rising like a cartoonish genre trap from the Montana plains. Precisely at this point is when we miss Cochrane’s and Foster’s shadowy performances, which deserved more scenes, but fell too soon to the episodic sequencing. Or worse still, we miss a deeper view into the trauma of Chief Yellowhawk and his family.

The trauma of war crimes as spread over the whites and the American Indians is a far more original—yet historically appropriate—canvas for the Western. Maybe no other genre can contain the full insanity of domestic conflicts of “justice” against “monsters” and the rational necessity of forgiveness.

Hostiles is a moody Western that makes us feel more deeply than many that have gone before. But it also reveals that violent content serves the formal haste of genre, trapping both trauma and forgiveness—the longer view of life—in an episodic reality. This life-or-death conflict over the ritual of genre is reason to see Hostiles twice or more.