In this issue: Wolfgang Palaver on Christianity and politics, more commentary on Gaza and Ukraine, upcoming events and invitations, reflections on annual meetings, three book reviews, and a bibliography of recent work on mimetic theory

Contents

Letter from the President: Nikolaus Wandinger, Thanks and Welcomes—Starting into a New Term

Editor’s Column: Curtis Gruenler, Mimetic Theory in Politics and Prison

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion, San Diego, California, November 23-26, 2024

Identity in Suspense, December 5-6, 2024, online

COV&R Annual Meeting, Rome, June 4-7, 2025

Lyle Enright, unRival Network’s Artisans of Peace Fall Cohort for Christian Leaders

Wolfgang Palaver, On the Dangers of a Return to Constatinianism

Weil Eggen, Girard and the Ukraine-Gaza Escalation

Theology & Peace 2024 Conference

William E. Cain, Mimietic Theory and Film edited by Paolo Diego Bubbio and Chris Fleming

Julia Robinson Moore, American Atrocity by Guy Lancaster

Andrew McKenna, Embodied Idolatry: A Critique of Christian Nationalism by Kyle Edward Haden

Bibliography of Literature on the Mimetic Theory: Dietmar Regensburger, Volume 51

Letter from the President

Thanks and Welcomes – Starting into a New Term

Nikolaus Wandinger

Dear COV&R members and friends,

As I am writing this piece for the Bulletin, I am sitting in the shade looking out at the waves of the sea thundering against the rocks of the island on which I am vacationing. I could hardly think of a more beautiful place to try and find some thoughts for the Bulletin. However, I can’t exactly tell you where I am, as this would kindle mimetic desires in you, respected readers, and that might have detrimental effects.

Okay—let us leave humor aside for a moment. I am writing this as the newly elected president of COV&R, and believe me, I am deeply honored by the trust the COV&R membership placed in me, and I have all the respect due to the task, especially when I remember whom I am succeeding.

Martha Reinke has summed up her work for COV&R in her wonderful essay in the last issue

of the Bulletin. But in addition to Martie’s service to COV&R, I am also thinking of the

many other presidents that went before. I don’t want to name them here, but I am awed at the

prospect of succeeding them as COV&R president. Shortly before this Bulletin was to be published, we got the said news that one former president, Cesário Bandera, has died on July 14. Cesário has contributed a lot to the literary application of mimetic theory (see obituary in this Bulletin). We pay tribute to his achievement in this field. I remember him as a very

friendly and warm-hearted person. My condolences go out to his son Pablo and his family.

Not only was the presidency of COV&R handed to another person at our Mexico meeting this past June but also the position of executive secretary, and many board members were newly elected to our advisory body. So, my first task is, again, to thank Martie Reineke for her outstanding leadership of COV&R and thank all COV&R officers who stayed in their jobs: Sherwood Belangia, William Johnsen, Curtis Gruenler, Chelsea King (who only recently succeeded Grant Kaplan), and Maura Junius. I also give my thanks to the outgoing Board Members: Ángel Barahona, Marinela Blaj, Wilhelm Guggenberger, Roberto Solarte, and Petra Steinmair-Pösel. It is of essential importance for the functioning of COV&R that we can fill the slots on our Board and that the elected board members then also fulfill their duties and, together with the president and executive secretary, steer COV&R through the tides of the times. Therefore, I am also very grateful to the persons who were willing to serve as new board members and whom the business meeting of COV&R in Mexico City elected by an overwhelming majority with two abstentions: Pablo Bandera, David Garcia Ramos, Martin Girard, Marina Ludwigs, Brian Robinette, and Julia Robinson-Moore. Welcome to the board! I am looking forward to working with you for the future of the Colloquium.

Finally, I want to mention that the COV&R membership at the business meeting elected Joel Hodge as the new executive secretary of COV&R. Joel is a long-term member, one of the most faithful attendees of COV&R events and meetings, and an experienced voice from our very active and productive Australian group. So, I am very happy that Joel, who will also be the main organizer of next year’s meeting in Rome, will be our executive secretary for the coming years.

I am also very glad that Suzanne Ross from unRival already reached out to me and Joel to discuss their future cooperation with and their support of COV&R. We are very grateful for that partnership and support. Let me add belated congratulations to Keith Ross for his 70th birthday at this point. Good wishes for your health and for you as a person with valuable ideas!

Of course, I also hope that the support of Imitatio, for which we are very grateful, will continue.

So, what’s next? After completing the wonderful vacation I am enjoying right now, there will be the actual transition of functions, the web page will be updated, and the new team will begin to work. As usual, next year’s conference, to be held in Rome from June 4-7, will be one of the main issues to be worked out. I trust it to be in very good hands with Joel, and he will write about it in a piece of his own. The course of the 2026 conference has also been charted already, with Maura Junius and Martie Reineke working to make it happen in Chicago from July 8 to 11. The next event will, of course, be COV&R’s activities at this year’s American Academy of Religion meeting in San Diego from November 23-26. So much for the look ahead.

I would like to end with the following remark: This year is a very important election year, in the U.S. and also in much smaller Austria where I live, and the world has become a more troubled place in the past few years. COV&R members have been entertaining quite different political opinions and allegiances, and I am sure they will continue doing so—it is a wealth that we have. I would just ask all of us to keep in mind: it is one thing to utilize mimetic theory to strengthen one’s own point of view and argue for it. It is another to use mimetic theory to critically question one’s own point of view and confront it with some reasonable doubt. I’d hope that serious mimetic theorists try to do both and not just stick to the first one. After all, it is not so easy to decide whom to give one’s support, as René Girard said in an interview with Nadine Normoy: “[W]e live in a world where everyone wants you to believe they’re on the victim’s side. […] And nothing is more difficult than knowing who the real victims are” (Nadine Dormoy, The World of René Girard, p. 57). Let us be careful to see the whole picture.

By the way: I was writing this text on the Azorean island of Pico—but don’t tell!

Editor’s Column

Mimetic Theory in Politics and Prison

Curtis Gruenler

René Girard’s work has received some attention in the mainstream American press recently because of vice presidential candidate J. D. Vance. Vance’s 2020 article “How I Joined the Resistance” includes a few short paragraphs about how Girard’s ideas influenced his conversion to Catholicism. Accounts of Girard’s thought I’ve seen in recent articles about Vance are brief and sometimes misleading, but this one, also occasioned by the U.S. release of Cynthia L. Haven’s collection of Girard’s writings, All Desire Is a Desire for Being, is better. Vance’s interest makes more urgent than ever the question of how mimetic theory might help us think about the relationship between religion and politics. So I am especially glad to have Wolfgang Palaver’s article, “On the Dangers of a Return to Constantinianism,” in this issue of the Bulletin.

The 2024 volume of Contagion, COV&R’s annual academic journal, is now available. It includes an article, “Violent Conflict, the Struggle for Identity, and the Contagion of Desire in the Prison Environment,” by Carlos Garcia, an inmate at the Muskegon Correctional Facility in Michigan and a student in the initial cohort of the Hope-Western Prison Education Program. I had the pleasure of getting to know Carlos in a course I co-taught for this program in which we read Girard’s I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. As I have heard Andrew McKenna say about his experience teaching mimetic theory to prisoners, Carlos and his classmates took to it right away. And for Carlos, this was just the beginning of a study that has born fruit in his first published article as well as in showing fellow inmates how mimetic theory can help them navigate imprisonment. I hope it will bear further fruit in writing and in guidance for change in the prison system. Members can access Contagion electronically as explained here.

Bill Johnsen has written a brief post on “The Staying Power of Girard” that also serves to introduce the latest volumes in the two book series he edits for Michigan State University Press. A 20% discount is available to COV&R members on the nine most recent books in Studies in Violence, Mimesis & Culture and Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory, including the four out this year: The World of René Girard, interviews conducted by Nadine Dormoy in 1988 and translated from French by William Johnsen; Cormac McCarthy: An American Apocalypse by Marcus Wierschem; René Girard and the Western Philosophical Tradition, Volume 1: Philosophy, Violence, and Mimesis, edited by Andreas Wilmes and George A. Dunn; and Playing Sociology: Theory and Games for Coping with Mimetic Crisis and Social Conflict byMartino Doni and Stefano Tomelleri. In addition, a 30% discount is available on selected titles from the backlist with a purchase of three or more. For more information, please see this page in the members section of the COV&R website. The same page includes a discount code for ordering through Eurospan, which has better shipping rates when ordering from Europe than ordering directly through MSUP.

A partial directory of COV&R members based on information submitted at the invitation of Mack Stirling earlier this year is being updated from our summer meeting. This link will take you to a page where you can enter your member number to download the directory as either a pdf document or an Excel spreadsheet. The same page has a link to submit your information for inclusion in the next update. For questions about your membership or access to the member pages on the website—or to join COV&R—see our membership services page.

Julie and Tom Shinnick’s read-aloud-and-discuss Zoom group is starting again on August 26 (note the new date, postponed from the announcement in the previous bulletin) with Tony Bartlett’s Signs of Change: The Bible’s Evolution of Divine Nonviolence(reviewed in Bulletin 72 by Scott Cowdell and by yours truly here). It meets weekly on Monday nights at 6:30-8:00 Central Time. New participants are welcome. As Julie puts it, “The read-aloud format provides an opportunity for rich discussion which members have greatly appreciated. It also helps readers and listeners slow down from our busy lives for a weekly period of reflection in a small community. We only read 10-20 pages a week, so it is easy to catch up if people have to miss a session or two. We record each session for anyone who misses a meeting and wants a copy. The recordings are private, and only sent to members who request them. About a week before the meeting I’ll send out a link for the zoom.” If you are interested, please email Julie.

In Memoriam

Cesário Bandera

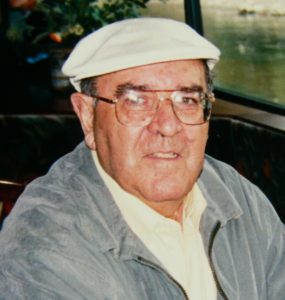

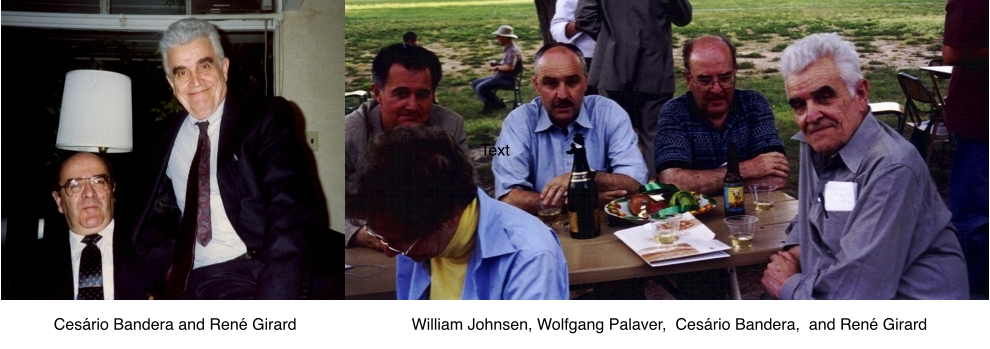

Cesário Bandera, COV&R’s president from 1995 to 1999 and an honorary board member, passed away in Laconia, New Hampshire, on July 14, 2024.

After receiving his Ph.D. in 1965 from Cornell University, he taught at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where he met René Girard in 1969—the beginning, he said, “of a fruitful lifelong personal friendship.” He finished his academic career as a University Distinguished Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1985-2002.

Four of Cesário’s books have been essential to the development of literary applications of mimetic theory:

- Mímesis conflictiva: Ficción literaria y violencia en Cervantes y Calderón. Prólogo de René Girard. Madrid: Gredos, 1975. French translation: Mimésis conflictuelle. Fiction littéraire et violence chez Cervantès et Calderón.Avant-propos de Paul Dumouchel. Préface de René Girard. Paris: Éditions Petra, 2016

- The Sacred Game: The Role of the Sacred in the Genesis of Modern Literary Fiction. Penn State UP, 1994. Spanish translation: El juego sagrado: Lo sagrado y el origen de la literatura moderna de ficción. Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla, 1997

- “Monda y desnuda”: La humilde historia de Don Quijote. Madrid: Iberoamericana, 2005. English version: The Humble Story of Don Quixote: Reflections on the Birth of the Modern Novel. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2006. Portuguese translation: “Despojada e despida”: a humilde história de Dom Quixote. Sao Paulo: Realizaçoes Editora, 2012

- A Refuge of Lies. Reflections on Faith and Fiction. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State UP, 2013. Spanish translation: El refugio de la mentira. Reflexiones sobre la fe y la ficción. Jerez: Libros Canto y Cuento, 2014

More recently, Cesário was a keynote speaker at COV&R’s annual meeting in Madrid in 2017. Among his surviving family members is his son Pablo, an incoming member of COV&R’s board.

A further obituary is available here. A Mass of Christian Burial will be celebrated on Saturday, September 14, 2024, at 10:00am at the St. Andre Bessette Parish – Sacred Heart Church, 291 Union Avenue, Laconia, NH.

Forthcoming Events

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion

San Diego, California

November 23-26, 2024

We will have two dedicated sessions at the upcoming AAR in San Diego. Registration for the AAR is open here, where the program, including times and locations of COV&R’s sessions, will also be announced.

Session 1: Intersections of Mimetic Theory: Theological Insights and Societal Responses

This session navigates the intriguing intersections and divergences within René Girard’s mimetic theory, especially in relation to contemplative theology and the sociology of disaster response. Through a pair of papers that critically engage with Girard’s work alongside contemplative texts and contrasting sociological observations, we invite attendees to a nuanced re-examination of mimetic theory’s scope and applicability. This session not only sheds light on Girard’s mimetic theory from fresh angles but also challenges participants to consider how the theory aligns or conflicts with other disciplinary insights. Attendees will be encouraged to think critically about the dynamics of desire.

- Susan McElcheran, University of St. Michael’s College: “Contemplation as Positive Mimesis: Desire and Knowledge in The Cloud of Unknowing and Mimetic Theory”

- David Smock, Arizona State University: “Paradise or Perdition: A Girardian Response to Rebecca Solnit”

- Kristoff Grosfeld, Princeton Theological Seminary: “Is God Violent? Mimetic Theory, Divine (Non)Violence, and the Possibility of Doing Theology”

Session 2: Exploring Mimetic Theory: Theological and Political Dimensions

This session offers an insightful exploration of René Girard’s mimetic theory through two papers that intersect theology, politics, and historical consciousness. By engaging with the works of F.W.J. Schelling, Bernard Lonergan, and Ignacio Ellacuría, the session highlights the transformative power of mimetic theory in understanding monotheism, the significance of the Cross, and the persistence of social sin. This session invites attendees to reflect on the complex ways in which mimetic theory informs our understanding of religious and political life, encouraging a reevaluation of our collective approach to history, theology, and the challenges of contemporary society.

- Chris Morrissey, Trinity Western University: “Monotheism, Intolerance, and the Path to Pluralistic Politics: A Schellingian Review”

- Matthew Cuff, Boston College: “The Politics of the Cross: Insights from Girard, Ellacuría, and Lonergan”

- Business Meeting

Identity in Suspense

Political and Aesthetic Articulations of Alterity

Viewed from Mimetic Theory and Psychoanalysis

Online

December 5-6, 2024

In his letter to Georges Izambard—dated May 13, 1871—Arthur Rimbaud coined a statement permanently linked to his name: “I is another.” These words by the French poet opened the abyss of subjectivity and blurred the defined limits of the Enlightened subject; identity and alterity became two poles that are mutually interpenetrated and are not separated domains divided by an unsurmountable border. Both for mimetic theory and psychoanalysis, this borderland is the realm of desire. The unrelenting crisis that shapes the contemporary world by accumulating conflicts reminds us of René Girard’s warning that we no longer live in times of war but in a state of war. War and social struggles are made in the name of an assumed identity to commit violence or resist it.

The theme proposed for this conference, “Identity in suspense: political and aesthetic articulations of alterity viewed from mimetic theory and psychoanalysis,” is an invitation to reflect on politics and art, putting the notion of identity in doubt to illuminate the intersubjective and relational environments in which it acquires consistency and meaning. A common trait between psychoanalysis and mimetic theory is their suspicion of a sovereign subject. Being is being for another—or through another—who could be the father or the Girardian mediator; nevertheless, the sense of self is always in relation to another. The task is to ask ourselves about the relation rather than the content: How is identity assumed in the commodified relational environment of late capitalism? How is identity articulated in the state of war of the contemporary world? Are there post-anthropocentric identities at the brink of climatic catastrophe? Is violence a generative principle of identity? Can art put identities in disarray to open up non-sacrificial spaces?

We want to dialogue with philosophy, humanities, psychology, psychoanalysis, and social sciences, as well as with decolonial positions. We believe that mimetic theory invites us to study and propose different approaches that help to think about identity, its relationship with the contemporary world, with violence among others. This is the reason why we have invited people from different fields of knowledge to participate in this meeting, always in reference to the mimetic theory as proposed by René Girard, and with the aim of having serious conversations that seek better understandings and solutions to the current crisis.

Finally, we invite papers (English, Spanish or Portuguese) that explore these and related issues from a wide variety of disciplines. Please send your abstract to Carlos Mora by October 1, 2024. The event will be held by streaming on December 5 and 6, 2024.

Spirituality, Religion, and the Sacred

COV&R Annual Meeting

Rome

June 4-7, 2025

It is exciting that COV&R’s 2025 conference will be held in Rome, Italy. It will be generously hosted by the Rome Campus of the Australian Catholic University.

We are hoping that this will be an attractive venue. The campus is located centrally in the suburb of Trastevere, with a range of hotels and restaurants nearby. There will be meals and some accommodation available on campus. Information about conference registration, accommodation, and the call for papers will be released on the conference website. The dates of the conference are earlier than our normal practice. This is due to the availability of the campus.

The theme of the conference is “Spirituality, religion, and the sacred” (a full description appears below). We are looking forward to announcing a range of topics, speakers, and forums to explore this topic.

I’m very pleased to confirm our first keynote speaker, Professor William T. Cavanaugh (DePaul University), who is the recent author of The Uses of Idolatry (Oxford University Press, 2024) about the persistence of worship in modernity.

The following outlines key themes of the conference to be explored:

The modern West has made a certain kind of subjectivity possible, if not compulsory: the self-identification of individuals as “spiritual, not religious.” Although common almost to the point of banality, this kind of identification is historically unique. While spiritual energies have been regularly deployed in times of religious renewal throughout Western history, no previous generation would have figured itself in quite these terms. And yet, from the enormous popularity of Russell Brand’s podcasts and online courses offered by publishing houses such as Sounds True, to the celebrity resurgence of Transcendental Meditation and the wide reach of Instagram yoga “influencers,” the pursuit of “spirituality” has come to be seen as the most intellectually—and perhaps politically—responsible way of approaching the transcendent.

The critique and disavowal of organized religion is undoubtedly part of the complex history of other critiques of authority which characterize modernity—of feudal power, of the power of the church, and, after the Second World War and the Holocaust, of national sovereignty and the “military industrial complex.” There is indeed much to recommend in the pursuit of spirituality—especially as it is connected to the yearning for authenticity, ecological holism, and a recovery of meaningfulness—and in turn, much to value in the critique of tradition and authority. The wars of religion (as much about national as religious sovereignty), the horrors wrought by the divine right of kings, and the atrocities which were endorsed by “official” science and state power in preceding centuries—and even our own—should give any thoughtful person some pause about submission to the arbitrary exercise of authority.

By the same token, however, this development has not given us a world free from sectarian struggle, human rights abuses, and new forms of authoritarianism, while the kinds of freedoms that were thought to be withheld by tyrannical traditions have not all eventuated. There are a host of reasons to doubt that “spirituality” in all its forms is an adequately sustaining force, and that the religious impulse can or should so easily be left behind. The turn to individualized forms of spirituality and the fragmentation of cultural and religious forms—especially as a number of lines of empirical evidence indicate the effectiveness of traditional forms in providing for human flourishing, transcendence, and sociality—poses fundamental questions about the liberal, “individualist” model of being human which achieved precedence during modernity. Attention must also be given to ways in which spirituality has been annexed by the commodity form.

These questions become more urgent when considered in the light of modern threats to human survival, particularly the extreme violence of modernity (e.g., world wars, terrorism, genocide, nuclear weapons) and ecological crisis. These threats indicate, if nothing else, that humans gravitate to cultural, political, and religious forms—which they so easily sacralize—to find fundamental meaning, social bonding, and transcendence, especially during crisis—even in an individualistic age, even when they are thought to have abandoned them. This apparent modern contradiction—increasing individualization accompanied by dangerous collective behavior—can be helpfully understood in the light of Rene Girard’s analysis of modernity and the foundational and regulative function of religion, along with his critique of a newly emerging post-secular sacred.

This conference seeks to problematize any too-simple disjunction between “religion” and “spirituality,” not least because “religion” and “secular” are freshly contested classifications that from a functionalist perspective can be seen to overlap. Accordingly, the conference will explore the possibility of a third way beyond the stale standoff between these modern categories. The implications of the investigation will entail, we believe, not only a different way of considering who we are—and might become—as individuals, but a novel reading of our unique historical moment, and how we have emerged into it.

Finally, I want to thank my colleagues at the Australian Girard Seminar, Professor Scott Cowdell (Charles Sturt University) and Associate Professor Chris Fleming (Western Sydney University), for working alongside me to organize the conference. I also want to thank Martha Reineke and the COV&R board for their assistance thus far.

Keep up to date with the latest information about the conference, including keynote speakers, registration and accommodation, at the 2025 Annual Meeting page.

Invitation

UnRival Network’s Artisans of Peace Fall Cohort for Christian Leaders

Lyle Enright

From the inception of the Artisans of Peace Program, the participants’ full humanity has been central. We’ve wanted to offer an open invitation to those of different backgrounds, complex experiences, diverse faith perspectives, and no faith at all. If it’s part of who you are, we want to make room for it through Artisans of Peace.

As a participant in the first Artisans of Peace cohort, I saw that invitation taken up with gusto. Many of my fellow sojourners were transparent about their spiritual backgrounds and commitments. They shared a sense of what John Paul Lederach calls the “heart and soul” of peacebuilding: an invisible fabric that underpins both violence and the possibility of peace. For them, peace work was a spiritual discipline.

As trust deepened, those inspirations overflowed. Many of the most energetic and exciting conversations I had during our in-person retreat centered on church communities, beliefs about God, and the transformative convictions of personal faith.

For a moment, it almost made me forget that the languages of religion and spirituality have so often been used to justify violence and dehumanization.

This has been especially true of my own faith tradition. Christianity, for many, is a religion of holy wars, displacement, and judgment. In the United States, contested visions of Christianity’s meaning now drive our politics. Many preach visions of divine peace and justice centered on the eradication of enemies.

Several participants in that first cohort, despite being Christians themselves, had first-hand experience being on the receiving end of Christian violence. What surprised me about these artisans of peace, though, was that their understanding of this painful, complex situation tended to make them more effusive about their faith. More in love with a God whom they believed identified with victims of violence. They did not respond to their situations with resentment or justification, but with hard-won joy and hope. It was almost as though they could not fully express their commitments to peace and justice without the specific language of their religious beliefs.

After sharing that experience, UnRival board member and Artisans of Peace alum Joel Aguilar and I decided to run an experiment—to take a risk. We wanted to test the value of gathering peacebuilders from diverse backgrounds, but similar faith traditions. Whose languages of faith and spiritual practice, so often sources of rivalry, might also help form a nonrivalrous community. This Fall, we are opening such a space in a new cohort of Artisans of Peace, designed for American Christian leaders who feel their own faith traditions contributing more towards rivalry and violence than to peace—and who want to change that.

Adapting Artisans of Peace for American Christian Leaders

We chose to focus on US-based Christian leaders in this cohort because Christianity, which has always been a dominant force in US culture and politics, is at a crossroads. With the noted rise of White Christian Nationalism as a major political force, pastors, teachers, and spiritual leaders face polarization in their communities and are drawn into increasingly rivalrous situations. While still committed to their faith, they are reevaluating their religion’s roles and forms in their communities.

As we’ve listened to potential candidates for this cohort, we’ve heard them describe their struggles as:

- The struggle to speak truth to power while also “loving their enemies”

- The struggle to serve the poor and the powerful with equal integrity, dehumanizing no one

- The sense that their own privilege and cultural dominance impedes acting out their faith

- Persistent fear of rejection or expulsion from jobs or communities because of their concerns for peace, justice, and the marginalized

- A general sense of dissonance between the values and actions of Christian institutions

Mostly, we hear a craving for a different kind of community: a place to be heard, to heal, and to confront the scandal of violent theology—both in our nation and in ourselves. A desire for what author Aimee Byrd calls “unpretentious companionship” between those tending their communities’ spiritual wellbeing amidst a storm of competing agendas.

This program is designed to refresh the hearts of US-based Christian leaders asking these sorts of questions, for whom the language of faith is essential but the path forward is unclear. They are buffeted by polarization but motivated by nonviolent theology and discipleship.

Our goal, in this specially adapted cohort, is to help pastors, artists, academics, and other Christian community leaders become “more human.” To open up space where they can wade into complexity. This will be a co-created space of safety and support where we practice trusting that, as theologian Willie James Jennings says, “The new always waits on the other side of risk.”

The Need for Nonrivalrous Space

Lutheran pastor and journalist Angela Denker writes, “simple narratives tend to sell better.” This can be even more true in religious environments, where spiritual leaders are often called on not to help people of faith grow and mature, but to provide reassurances of personal goodness and identity.

The spiritual leader is saddled with a role that is at once “managerial and messianic,” Aimee Byrd writes, expected to step into others’ hurts and messy lives with all the aplomb of a seasoned project manager, equipped with all the latest knowledge and content that will solve everybody’s problems. Spiritual leaders, constantly faced with their congregations’ high expectations of personal and political reassurance, find themselves friendless, lonely—even dehumanized. Certainly under-equipped for peacebuilding.

Our friend Patty Prasado-Rao echoed the need among pastors and spiritual leaders for nonrivalrous spaces like those we provide in Artisans of Peace: “It’s like everything is against us making those nuanced connections,” she told us. “It no longer feels like ‘the answers’ are answering anything. [These leaders] know that those under them will be shaken to learn that they don’t feel strong or confident… [But] if there is even such a thing as a theological basis for peace work, where is it? Where is the theology, where is the base? Where are the places for [them] to share their own questions, their own fears, their own difficulties?”

We believe Artisans of Peace provides the blueprint for such a space, one that can be adapted to provide spiritual leaders with the time and attention to watch and strengthen their webs of relationship. Here’s an idea of what to expect from this cohort:

- A Space of Silence and Attention. Spiritual leadership, Byrd writes, quoting author Eugene Peterson, “is ‘the act of paying attention to God, calling attention to God, being attentive to God in a person or circumstances or situation.’ This requires a slowing down, a listening, a looking, contemplation, prayer, doing what looks like nothing.” Among those we’ve spoken to about Artisans of Peace, many crave spaces where they can be silent together, building trust and community through that willingness to sit in silence rather than “fix” each other in “project manager mode.” Artisans of Peace assumes that need for silence, drawing on the wisdom of many religious traditions. It is readily adaptable to the specific rhythms of prayer and contemplation that many spiritual leaders find themselves lacking right now.

- A Space of Encounter and Belonging. Byrd continues that the vocation of spiritual leadership demands “[R]everence for people’s secrets, embracing the holiness of encounter, and curiosity and imagination to see the Spirit working at this moment. It is a refusal to accept the faces that are being presented—both the virtue and the vices that mask our untold stories—and get a glimpse of the work that God is inviting us into together.” In Artisans of Peace, we allow the masks of what we’ve accomplished to slip, revealing who we are in a space of mutual learning. Spiritual leaders also need space to shed these masks together, and this is especially true for peace-minded Christian leaders who face such aggressive expectations about their own vocations.

- A Space of Refreshment and Celebration. Each of us has dozens of occasions every day to say what we’re against. Artisans of Peace is a space for celebrating what we’re for: what we desire, who taught us to desire it, and what sustains our hope that the world really can change for the better. Almost all the leaders we’ve spoken with also share faith in a spiritual force that is slowly, persistently making all things new. Spiritual leaders need spaces where we can use that language, where they can laugh and cry about the beauty they still find in their religious traditions, despite rivalistic uses of that language. Spirituality doesn’t need to be serious and heavy all the time; at its best, it is a source of deep joy, levity, and sustenance.

- The Creative Surprises of Grace. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus says, “Where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them.” This cohort takes that spiritual instruction to heart, but also believes in the very concrete, earthy wisdom of it: we’re better together. Our differences breed creativity and affirmation. Where our hearts and attention are trained towards each other, new possibilities show up in surprising, transformative ways.

Everyone–even the humblest of peacebuilders and spiritual leaders–need nonrivalrous spaces and practices to sustain them down the uncertain road ahead. If this sounds like you or someone you know, please get in touch. We’re eager to hear from you.

Commentary

On the Dangers of a Return to Constantinianism

Wolfgang Palaver

After Peter Thiel gave his keynote address, “Nihilism is Not Enough,” at our annual meeting in Paris 2023, he was asked by his respondent Frederic Worms what would possibly be enough—or, if there is nothing that is enough, what would be necessary—after Thiel referred to a long list of concepts and perspectives that are not enough (philosophy; scapegoating; katechon; early, middle, and late modernity; decadence; Hamlet). Thiel’s answer was that he, like Girard, does not provide positive answers but sees the avoidance of the Antichrist (identified with a totalitarian world state) as the most important task of today. I disagreed regarding Girard and referred to his pointing to religion when people questioned him what they should do. He either recommended to them that they should go to church or even mentioned saintliness as an important personal goal to aim at.

When Thiel delivered this paper at the Novitate Conference at the Catholic University of America in Washington in Fall 2023, he explicitly addressed during the discussion also his view of Christianity. I did not attend this conference but heard from Curtis Gruenler and others that he summarized his attitude with the provoking statement that he prefers “the Christianity of Constantine to the Christianity of Mother Theresa” (Gruenler).

When I read this statement, I was worried because it could recommend a type of Christianity that I hope the churches overcame decades ago. I asked Thiel how he meant his provoking thesis, and he told me that his main aim was to defend an understanding of the church that is not completely powerless or apolitical. According to him, it is necessary to find a proper relationship of the church with the state. An apolitical church is, in his eyes, not able to prevent the persecution of Christians. He also maintained that historically a Constantinian type of Christianity was the best that could have been achieved at that time. He understands it, with Girard, as a form of “historical Christianity” and as a “katechon,” a restrainer of the Antichrist (mentioned in the Second Letter to the Thessalonians). I agree with this historical evaluation. He again agrees with Girard and me that it is impossible to return to Constantine’s Christianity. By pointing toward Constantine in order to turn away from an apolitical Christianity, however, he plays with fire, if one understands the dangers that are connected with the Constantinian legacy. There are much better options for a proper understanding of a politically engaged church.

In the following I will explain why I think that from Girard’s perspective it is neither possible nor desirable to return to Constantine. I show in what sense a Constantinian version of Christianity would significantly deviate from Girard’s understanding of it, would also fall behind the Second Vatican Council of the Catholic Church, and would even deviate from a main dimension of the post-axial religions.

With the term Constantinianism I do not address the personal faith of the Roman emperor but the amalgamation of church and political power that is usually connected with his name. With Constantine’s deathbed conversion, Christianity no longer remained a religion of a small minority in the Roman Empire but began to become its dominant religion. During Christian history, this Constantinian and imperial legacy shaped the relation between church and political power in various forms. John H. Yoder rightly observed, in an insightful essay, that not only Catholicism embodied this dangerous alignment of the church with political power; later movements that fought against it were not able to overcome it but led to versions of it that were even more problematic (Yoder, pp. 135-147). As an example, he mentions those Protestant churches that fought against the Constantinian Catholicism but resulted in an even closer alignment with a particular nation state.

To understand the dangers coming along with a Constantinian interpretation of Christianity, we can turn to the political theology of the infamous German law scholar Carl Schmitt, who endorsed a Constantinian church that seeks to govern and dominate worldly affairs. In his book Roman Catholicism and Political Form, he understands the Roman Catholic Church as a “world-historical form of power” (Schmitt, p. 21). He neither puts the longing for eternal goods first nor does he understand how central servanthood and the cross are to avoiding mimetic rivalries in the way Jesus showed us to do. A hugely different Christ characterizes Schmitt’s understanding of the Church when he states that “it represents Christ reigning, ruling and conquering” (Schmitt, p. 31). Schmitt’s book appeared more than one hundred years ago and might be seen as a work that has nothing to say to our current world. Schmitt, however, is today widely read all over the world. His work is eagerly consulted in China and Russia and has also influenced those ideologues who call for a new Christian nationalism or support the revival of a Catholic integralism (Lilla).

A careful reading of Girard’s oeuvre shows his critique of a Constantinian view of Christianity. There is a passage in his book The Scapegoat that describes how the Constantinian legacy turned the religion that revealed the persecutory dimension of early religion into a religious system with its own type of persecution:

Beginning with Constantine, Christianity triumphed at the level of the state and soon began to cloak with its authority persecutions similar to those in which the early Christians were victims. Like so many subsequent religions, ideological, and political enterprises, Christianity suffered persecution while it was weak and became the persecutor as soon as it gained strength. (Scapegoat, p. 204, translation corrected)

Close to what Yoder has observed in his essay, Girard also remarked in a radio interview with David Cayley that criticism of Constantinianism is, however, not protected from being contagiously infected by the very violence that it wants to overcome:

Christianity first becomes an establishment under Constantine. You denounce it. Then there’s the Inquisition, followed by the Renaissance and the Reformation. The Reformation says, we are going to be that perfect church that the Catholics were not able to be. But after a few centuries, they become the same. And it doesn’t stop there. They will be criticized, too. And then they all survive together. They become a horrible big mess. But the spirit of critique is always more powerful than the institution. And what we must try to purify is that critique. Critique always embodies an element of the same violence it is criticizing. It’s always in the same circle of violence. (Cayley/Girard, p. 32)

What Girard addresses in this warning is the real temptation of the Antichrist that means to follow Christ but only leads to a scapegoating of scapegoaters or to “a hunt for scapegoats to the second degree” (I See Satan, p. 158).

In an interview from the late 1980s, Girard expressed his distance from Constantinian concepts by referring to the Biblical principle “of give unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, and unto God what us God’s” and to the “idea that Satan is the prince of this world,” therefore claiming that the “absolute separation between religion and the state is essential” and that it “is clearly affirmed in the Gospel” (Dormoy/Girard, p. 56).

Girard deals with the Constantinian temptation even more broadly in the chapter “The Pope and the Emperor” in his last book Battling to the End. He focuses on the history of the papacy and shows how it slowly was able to detach itself from political power and won through this its moral authority. He sees a culmination of this in Pope John Paul II’s repentance by confessing the sins of the Church in the year 2000:

When I say that the papacy won, I am thinking immediately of this repentance, by which the papacy triumphed over itself and acquired worldwide significance. Before our eyes, it succeeded in expelling all imperial ideas, at the very point when its temporal power disappeared. (Battling, p. 200)

In this chapter of Battling to the End, Girard remarks that the Byzantine Empire did not know this separation from worldly power that has increasingly characterized Western Christianity (Battling, p. 200-201, 209). This insight helps us to understand the problematic position of the Russian Orthodox Church of today that legitimizes Putin’s war of aggression against Ukraine as a “holy war.”

Girard praises in this chapter also Pope Benedict’s opposition to any “compulsion” in religion (Battling, p. 209) and underlines by this the endorsement of religious freedom by the Second Vatican Council of the Catholic Church:

If Vatican II did one essential thing, it was to assert religious freedom, for if there is one single thing that Christianity cannot violate, it is the freedom to reject Revelation. (Battling, p. 199)

Girard reads the Biblical revelation—especially the teachings of Jesus—in the same way as the fathers of the Second Vatican Council who understood that it excludes compulsion in religion. The most decisive step of the Catholic Church in our modern world was indeed its overcoming of Constantinianism in the Second Vatican Council. The declaration on religious freedom Dignitatis humanae, in which coercion in matters of religion is clearly rejected, is one of the most important documents of the Council. According to this document, religious freedom finds its justification in the Biblical revelation. Dignitatis humanae openly declares that the Church must reject all means that “are incompatible with the spirit of the Gospel” (No. 14). The example of Jesus Christ—his nonviolence, patience, and rejection of force—must also become the way of the Church: “Christ is at once our Master and our Lord and also meek and humble of heart. In attracting and inviting His disciples He used patience. […] He refused to be a political messiah, ruling by force. […] He acknowledged the power of government and its rights, when He commanded that tribute be given to Caesar: but He gave clear warning that the higher rights of God are to be kept inviolate: ‘Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s’ (Matt. 22:21)” (No. 11). This biblical turn of the Council has become the starting point of the Catholic social ethics as Pope John Paul II later developed it. This pope brought the legacy of the Council to its blossoming. He was really the first non-Constantinian or post-Constantinian pope, a fact that Girard highlighted by praising the Pope’s repentance in 2000.

A return to a Constantinian understanding of Christianity goes, however, even beyond Catholicism because it challenges a key dimension of all postaxial religions that are characterized by their awareness of a transcendence that relativizes all worldly power and allows for the first time in human history a distinction between politics and religion. Unfortunately, the postaxial religions remain tempted to fall behind this religious achievement, as history shows. And this temptation is still with us if we think of the Hindutva movement in India that tries to create a Hindu state, of attempts in certain traditions of Islam to create a caliphate or an Islamic state, or of today’s Russian Orthodox Church, and of the rising Christian nationalism in the US and other countries. Whatever one thinks of Emperor Constantine’s personal faith, this brief essay should convince its readers that we should not return to a Constantinian understanding of Christianity.

My critique of Constantinianism, however, does not mean to opt for an apolitical Christianity. In this regard I side with Peter Thiel, at least to a certain degree. His statement is provoking because by opposing Constantine to Mother Theresa he contrasts an imperial type of church with a saintly person that presents an apolitical understanding of the church. I remember that as a student we argued with the church hierarchy at that time who always preferred Mother Theresa over our political activities following liberation theology or people like Oscar Romero. My knowledge about Mother Theresa is not enough to judge if she really was apolitical. My worries with Thiel’s statement stem from the fact that there are many different viable solutions for a political church between these two extreme poles. This essay tried to emphasize the dangers that a return to Constantine would bring with it.

Thiel’s statement asks for a positive response regarding a political type of church and its proper relationship to the state. Such a response also needs to show what a Christian understanding of the katechon might look like today. This will require another essay that I hopefully can draft soon. For a quick response I often refer to Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s understanding of the relationship between the katechon and the church, in which he significantly differed from Carl Schmitt’s Constantinian endorsement of the katechon (Palaver, pp. 20-21). Schmitt viewed the katechon as a Christian concept of order by overlooking the fact that it not only restrains the Antichrist but also postpones the second coming of Christi. Bonhoeffer wrote that the katechon is neither identical with God nor without sin but is sometimes necessary to preserve the world from destruction. The church cooperates with the katechon without neglecting its primary task to embody “the miracle of a new awakening of faith” that provides orientation for the katechon, too. A proper unfolding of this difference will hopefully follow soon in one of the next issues of the Bulletin.

References

Girard, René. The Scapegoat. Translated by Yvonne Freccero. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

________. I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. Translated by James G. Williams. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2001.

________. Battling to the End: Conversations with Benoît Chantre. Translated by Mary Baker Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. East Lansing, Mich.: Michigan State University Press, 2010.

Girard, René, and David Cayley. The Scapegoat: René Girard’s Anthropology of Violence and Religion. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Radio Interviews from March 5–9, 2001. Toronto, 2001.

Girard, René, and Nadine Dormoy. The World of René Girard: Interviews. Translated by William A. Johnsen Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2024.

Gruenler, Curtis. “Be Not Conformed.” The Bulletin of the Colloquium on Violence & Religion, no. 78 (December 2023).

Lilla, Mark. “The Tower and the Sewer.” The New York Review of Books 71, no. 11 (2024): 14-18.

Palaver, Wolfgang. “Sacrifice and the Origin of Law.” In Law’s Sacrifice: Approaching the Problem of Sacrifice in Law, Literature, and Philosophy, edited by Brian W. Nail and Jeffrey A. Ellsworth, 12-22. London: Routledge, 2019.

Schmitt, Carl. Roman Catholicism and Political Form. Translated by G. L. Ulmen. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Second Vatican Council. “Declaration on Religious Freedom Dignitatis Humanae: On the Right of the Person and of Communities to Social and Civil Freedom in Matters Religious.” 1965.

Yoder, John Howard. The Priestly Kingdom: Social Ethics as Gospel. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984.

Girard and the Ukraine-Gaza Escalation

Wiel Eggen

To take on Phillip Bodrock’s challenge in his reply to Mark Anspach’s pointed Letter from the Negev (see Bulletins 78, 79, and 80) means entering into an escalating worldwide dispute with roots in a religious controversy that Girard spent much of his life to try and unravel. As a Dutchman writing from Poland, on how the Gaza war dovetails into Putin’s Ukrainian “operation,” I realize that these two nations, like so many others, have been part of this ordeal from the very start and are called to help deescalate and solve it. After the Nazis accrued their crimes on Polish soil as if minding Caiaphas’s order (cf. John 19:14) to sacrifice some so as to save humanity from ruin, the Netanyahus together with many other Polish migrants expectantly went to make Israel a new home. On the Dutch side, support of that Israel has been firm; but so was also their Premier Lubbers’s lobbying for an Energy Union with Russia, during his 1991 EEU presidency at Maastricht; which was to lead to a dependency that proved beset with grave dangers, once Putin chose to tackle the West’s global hegemony. Although these facts may seem unrelated, we will note how the present Gaza drama fits into the violent project that Putin and his advisers, like the far-right political philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, engage in. Shortly before he launched his 2022 Ukraine “operation,” Putin termed this a fight against the “polonization,” by which term he referred to an old East-West church polemic in Ukraine, thereby giving his political ideals a tint of religious rivalry Girardians are called to analyze.

Is it conspiracy thinking on our part to follow the analysts that saw the Gaza drama fit in with the Kremlin plans to sacrificially insert various belligerent parties into a wider combat? Let us ponder this coincidence, how shortly after the ICC in The Hague had sentenced Putin for his Ukrainian crimes, which stopped him from attending the vital BRICS meeting in South Africa, the Hamas carnage provoked Israel’s predictably harsh retaliation, inspiring South-Africa’s ANC promptly to go and indict Israel in The Hague of possible genocide and of war crimes similar to Putin’s. Taking into account Moscow’s long-standing support of the ANC anti-apartheid struggle and its more recent aid to Palestinians, the said analysts conjectured that the Kremlin saw the strategic opportunity to strike at the West’s Achilles heel in the Middle East so as to divert public attention away from its (ailing) Ukraine operation. Indeed, the Gaza war made the USA put on hold its massive aid to Ukraine and weakened the European media’s indignation over Russia’s invasion. Through acts like the Houthi attacks on the Red Sea shipping lanes, the escalating global conflict came to appear as a case of Israel with its Western supporters having actually provoked a justified revolt.

Bodrock rightly observes that peace will be elusive as long as Israel and Palestine remain enemy brothers, and many a Girardian has commented on this standoff. But which peace is meant? May one not discern a geopolitical plot behind this drama that dates from well before the Shoah and deserves an analysis in wider Girardian terms? Clearly the shots are called from afar, where “escalation to the extreme” is a stated strategy, and brinkmanship a favorite game. Whichever Gaza peace plans may arise, the cards in US hands will be challenged by the alliance around the Kremlin, whose friends in BRICS, along with many countries seeking to shake off Western controls, tend to exonerate Hamas. And the moral anger among intellectuals over Israel’s rude retaliation now starts to eclipse the one over events in Mariupol, Kiev, or Kharkiv.

How to assess this in Girardian terms? Reflecting on Islamist violence in Battling to the End, Girard saw the “escalation to extremes” enter a new phase. But as reactions to the double-edged Gaza drama waver on which side to back and whether the West’s claim that Israel is fighting for democratic values can stand, a Girardian analysis will no doubt have to consider Putin’s project and its backing by the BRICS associates. On the other hand, the shifting moral anger also holds a prophetic, say Girardian, inspiration about the democratic values Israel and its supporters are alleged to defend against what is unfolding. The weight is tilting to a division that has so far hardly been noted. Where Putin and the Islamists both refute the “absolute priority of the individual,” on which democracy boasts itself to rest, and even dub it the root of a recurrent fascism, the question arises if this does not somehow echo a basic Girardian concern, making his notion of “interdividuality” score well in various circles, whether or not they forswear violence.

In this context, we may consider the extremes to which Putin has been going in his “anti-polonization” fight. After showing pitiless brutality in Chechnya and Georgia, and while preparing to attack Ukraine’s Crimea, Putin is strongly believed by many to have dared a most hideous offense. This happened in April 2010, against the Poland that once hosted the military counterpart of NATO in the Warsaw pact, which was home to the Pope who made the Soviet empire unstitch, and whose President Lech Kaczynski was siding with Georgia’s liberals. Having reluctantly agreed to erect a monument for the thousands of Polish WW II officers executed in 1940 at Katyn under Stalin, and to join Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk for the inauguration of this memorial, he insisted that President Kaczynski—opponent of Tusk’s party—shouldn’t visit that place until the next day. The Polish presidential Tupolev-jet had been in a Moscow “service” for six months and had been returned just for this flight. Before Pres. Kaczynski and nearly one hundred officials took off, the special air control equipment that was installed on Smolensk airfield for the Putin and Tusk flights was secretly removed. When an unexplained mist suddenly covered the airfield and faulty orders from the control tower made the pilot fatally lower his course, a crash-with-explosion followed. Putin adamantly claimed the right to investigate the event and all evidence was moved to Moscow; flight boxes were meddled with, the victims’ remains were fumbled, and when finally the coffins were released, Polish relatives were told not to open them. As this order was ignored, the scam was discovered, including traces of explosives that are held to have blown up the plane in the air before touching the trees. Nonetheless, Tusk was persuaded to let the issue rest, so as not to endanger EU-Russian relations, and notably the North Stream energy project. After being voted out and indicted of this negligence and other issues, of which he was oddly acquitted, Tusk was offered the Brussels EU presidency. To Putin this signaled that he could safely go ahead in his adventures, such as the 2014 invasion of Crimea, and test the West’s coherence.

We perceive four dissimilar sacrificial excesses that Girard’s theory may assimilate. The crashing of a President’s plane for siding with the opponent is truly sacrificial; but so is letting this go unchallenged for material gain. And in the Gaza-controversy we see collateral damage being taken for granted as listlessly as the brutal murder of innocent civilians to allegedly compensate for ongoing oppression. With Patriarchs and Ayatollahs approving of such atrocities as torpidly as Chaplains may extenuate the collateral damages, we see an escalation to extremes that Girard in his Clausewitz study saw developing in the modern state monopoly of violence and in the revolts it provokes. But we note that this occurs in a new international realm where opponents share a globalized power scheme under the overarching frame of a nuclear deterrent that functions as a new “umbrella of divine order.” In my work as a chaplain studying Girard’s career with students, we perceived a new setting, where medieval methods of torture grow into mimetic extremes of State terror. But the belief arose that Girard’s Christian perspective, culminating in his Clausewitz study, might hold a solution.

As we read Girard’s career via the lens of his Augustinian-type conversion, as Joseph Niewiadomski has also proposed of late, its core appeared to be his radical critique of the West’s sacrificial view of redemption, which made the saving cross paradoxically turn into a source of reviled individualism. The idea that Christ’s gracious salvation offered a personal election could easily inspire hegemonic arrogance, while inversely, the divine Father’s demand of sacrificial obedience tended to incite atheist revolts and a Promethean type of rivalry that challenged eternal rules in matters of technical and social power, from medicine to ecology. In Girard’s vision, the ensuing escalation to extremes can be curbed only if this sacrificial reading of the Gospel is inverted. That would facilitate a new dialogue with the Orthodox and the Muslim hermeneutics of Christ’s prophetic message. Islam actually originated as a critique of the Pauline vision of Jesus (Isa) as a divine son sent to save humanity by a ritual sacrifice, which obscured the Q-tradition of the Gospel stressing ethical love and trust in the divine clemency. In turn, such a new focus on social coherence, in Girard’s understanding of “interdividualism,” will also align with the Orthodox focus on St John’s tradition of love, which sees the essence of human life rooted in God’s Trinitarian union.

As the violent extremes are escalating to World War proportions, and a ceasefire with occasional shooting across demarcation lines is no solution, a trilateral reflection on the basis of Girard’s anti-sacrificial reading of the Gospel is indicated. To review the prophetic roots of these belligerent traditions and integrate the three hermeneutic lines anew, while we recognize the deviations that have engendered such ugly rivalries by ignoring the prophets’ order to halt each other’s victimization, may enable a collective resolve to face the mounting challenges of climate, biodiversity, and poverty crises. Putin’s stated ideal of a multipolar balance underpinning the BRICS opposition to Western hegemony is also bound to be stillborn without a shared reflection on its ideological roots of power and rivalry. Girard’s innovative view seems well designed to help realign the three hermeneutic lines of the Gospel that are underneath the conflicting social constructs.

Event Reports

COV&R 2024 Annual Meeting

The Main Program (by Curtis Gruenler)

It was a joy to see and meet so many members at our Mexico City conference in June. Many thanks to Tania Checchi for her superb orchestration of all the arrangements, along with her local team, an excellent audiovisual support crew, and the ever-helpful David Garcia-Ramos and Blanca Millán. All of the sessions were recorded and will be posted to COV&R’s YouTube channel, pending permission from presenters. If you were a presenter, you can indicate your permission (if you haven’t done so already) by filling out this form.

The Colegio de San Ildefonso more than lived up to its billing as a friendly and inspiring meeting site. Founded as a Jesuit School in 1588, the building, with its spacious courtyards and arcades, came in 1867 to house the National Preparatory School. Among its alumni are Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes, and Frida Kahlo. In the 1920s, Mexico’s muralists filled its walls with murals. Today, it is an art museum and cultural center with meeting rooms for lucky organizations like COV&R. As outgoing COV&R president Martha Reineke wrote when she posted the accompanying photo on Facebook, “Being able to walk through the building and take in its beauty in the morning light, in the warmth of the afternoon, and after dark was just extraordinary.”

The Colegio de San Ildefonso more than lived up to its billing as a friendly and inspiring meeting site. Founded as a Jesuit School in 1588, the building, with its spacious courtyards and arcades, came in 1867 to house the National Preparatory School. Among its alumni are Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes, and Frida Kahlo. In the 1920s, Mexico’s muralists filled its walls with murals. Today, it is an art museum and cultural center with meeting rooms for lucky organizations like COV&R. As outgoing COV&R president Martha Reineke wrote when she posted the accompanying photo on Facebook, “Being able to walk through the building and take in its beauty in the morning light, in the warmth of the afternoon, and after dark was just extraordinary.”

The Colegio’s site across the street from the ruins of the Templo Mayor, the main temple of the Mexica people in their capital, Tenochtitlan, could not have been more evocative of the conference theme, “Desire among the Ruins: Mimesis and the Crisis of Representation.” The temple, built in the 1300s, was destroyed by the Spaniards in 1521. Stones from the temple were used to build the Metropolitan Cathedral, located on the other side of the temple remains from our meeting place at the Colegio. Not until the late 19th century, however, did archeologists first discover evidence of the former Aztec temple beneath the cathedral. And not until the 1970s were remains of the main temple accidentally discovered adjacent to the cathedral by utility workers. It remains an active archeological site, with an adjacent museum displaying its artifacts and attempting in various ways to represent what is lost.

The juxtaposition of the two sacred sites, ruined temple and active cathedral, also recalls the violence in 1519, preceding the destruction of the temple. Eight to ten thousand Aztecs were massacred on the temple grounds by the Spaniards, and the Aztecs captured ten Spaniards and sacrificed them in the temple. One of the most powerful murals in the Colegio is “Massacre at the Templo Mayor” by John Charlot, who was 24 in 1922 when he painted it.

Carla Canullo’s plenary address, “The Ruins of Representation,” offered a Girardian understanding particularly apt to our site. She said that the image of a ruin is given as an image of lack. When we see ruins, we desire not simply to fill what is lacking but also to add to the ruin what is missing. But restoration cannot bridge the distance. Ruins look at us and follow us with the emptiness of their pupils. The connection to the scapegoat is that in crises, social relations crumble. We blame a scapegoat. It threatens us, giving us the same look as a ruin. Ruins are therefore a representation of the sacred in its Girardian sense. And the background of the sacred is the feeling of shame. Shame precedes representations of the sacred and ruins them. Indeed, shame precedes every form of the sacred.

As at our previous annual meetings, the program was remarkable for its interdisciplinarity. Presenters in both plenary and parallel sessions addressed the theme from disciplines across the social sciences and humanities: anthropology, philosophy, art history, politics, theology, history, literature, technology, film, peacemaking—all in the spirit of open, inquisitive conversation that makes COV&R so stimulating and fruitful.

Besides mimetic theory, phenomenology was a second center of gravity that many of the plenary sessions revolved around. Several speakers touched on the work of Emmanuel Levinas, as when Stéphane Vinolo of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, raised the difference between desiring an object and desiring a face. René Girard is, for me at least, primarily a reader of texts, but these presentations brought out how his work can be complemented by, and perhaps even has an element of, phenomenology’s style of direct attention to lived experience. On top of mimetic theory and phenomenology, Columbia University’s David Freedberg, who has collaborated with Vittorio Gallese to investigate empathetic responses to images in light of the discovery of mirror neurons and embodied simulation, brought to bear the results of empirical research on mimesis at the neural level for a “bottom-up” view of basic human reality, prior to cultural mediation. “We underestimate,” Freedberg suggested, “the possibility of cross-cultural understanding.”

Like mimetic theory, phenomenology goes hand in hand with the question, framed most urgently in the Belfast accent of Ulster University’s Duncan Morrow, “What do we do?” As Sandor Goodhart of Purdue University remarked in a parallel session, if Girard provides the diagnosis, Levinas offers an ethical response. More than one speaker also turned to Jean-Luc Marion on the contrast between idols and icons and the desire for saturated experiences. Carla Canullo of the Università di Macerata, for instance, suggested that images of ruins saturate our seeing with a lack that desire seeks to fill. I found a consistent thread of asking how the desires evoked by images might point in a hopeful direction. While “positive mimesis” can, as Chris Fleming noted, have too much of a connotation of positivist certainty, reflection on ruins may clarify the difference between models of, as Morrow put it, “desire that leads to humanity or desire that leads to death.”

COV&R’s tradition of sessions devoted to recent books continued this year with Scott Cowdell’s Mimetic Theory and Its Shadow: Girard, Milbank, and Ontological Violence and the brand new collection of chapters by many hands, René Girard and the Western Philosophical Tradition, Volume 1: Philosophy, Violence, and Mimesis, edited by Andreas Wilmes and George A. Dunn. Volume 2 will include an article by Geoff Shullenberger that he previewed in “Violence after Sacrifice: Girard, Foucault and Nietzsche’s Shadow.” Jean-Pierre Dupuy’s talk introduced the argument of his recent book, The War That Must Not Occur, by way of a compelling commentary on Christopher Nolan’s film, Oppenheimer.

This meeting also continued the more recent tradition of making space within its academic emphasis for turning theory to practice. UnRival sponsored an Art and Peace Café, as described below. The “Peace Panel” on the final morning tried a more interactive plenary format, with brief thoughts on the practice of peace from Reineke, Morrow, and Wolfgang Palaver seeding small-group discussion and sharing among attendees. Most of the plenary sessions, in fact, included a goodly amount of time for dialogue with the speakers, which, helped by the microphones in each room and often Tania Checchi’s own service as an interpreter, I found to be the most lively and engaging part. As Morrow had said in his previous plenary, “When we meet each other, both truth and the possibility of reconciliation emerge and are inseparable.”

One of the highlights of every COV&R meeting is the annual Raymund Schwager Award for best papers given by graduate students. This year’s first prize winner was Pierre Azou, a Ph.D. student at Princeton University in the Department of French and Italian with a Bachelor of Arts (2012) and a Master of Public Affairs (2014) from the Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris (Sciences Po.), as well as a master’s degree in French literature from the Université La Sorbonne-Paris IV (2017). An emergency prevented him from attending, but a video of his paper, “Envy, Images and Dating Apps: ‘The End of Love’ According to Girard,” will be posted with the rest of the conference proceedings.

A second Schwager Award was given to Nicolas Aguia, a student of Roberto Solarte at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogota, Columbia, who went on to receive a Ph.D. in music composition from the University of Pittsburgh and is now a Ph.D. student in Latin American languages and literature at the Ohio State University. His paper was titled “Mimetic Images of Conflict and Accumulation: Negative Reciprocity in José Maria Arguedas’ Every Blood.” Its final section turns to the novel’s resolution of its violence through music: “Music interrupts rising conflict,” Aguia argues, and redirects “social relations to an object that no one can consume or appropriate.” His words brought to mind for me Dante’s use of music as a metaphor in the Paradiso for polyphonic relational harmony, which, in turn, captures my experience of our meeting: an extraordinarily diverse group enjoying the relations to each other mediated by our shared exploration of human reality, opened for each of us in some way by mimetic theory.

A highlight for many this year was the Thursday evening screening of the almost-final version of Sam Sorich’s film, Things Hidden: The Life and Legacy of René Girard, fresh from receiving the award for Best Documentary Feature at this year’s Avignon International Film Festival. Full of archival footage and exclusive interviews, it not only teaches and delights but moves. We hope to have more news soon on further opportunities for viewing.

Art and Peace Café (from Lyle Enright, for the unRival team)

This year at COV&R, unRival Network had the absolute privilege of providing a space of welcome and excitement. Through food, music, and easygoing conversation, peacebuilder and unRival board member Joel Aguilar along with singer-songwriter and activist Diana Gameros invited attendees of this year’s Colloquium on Violence and Religion to see each other in new ways at unRival’s Art and Peace Cafe.

It’s easy to get excited about new ideas; at the Art and Peace Cafe, we reconnected with the people those ideas come from, “interdividuals” in real contexts, formed by places they love. Joel and Diana introduced a gentle, generous pause into the week so that we could have such an experience of one another.

We didn’t expect just how transformative the experience would be for some attendees! When lunch was over, everyone commented not only on the conversation, but on the space: the placement of the food, the feel of the chairs, the easiness of the atmosphere. We were already provided with a stunning, open room by Tania Checchi and our hosts at the Colegio de San Ildefonso in Mexico City. With the help of some patient and dedicated caterers and technicians, our guests felt free to move around, meet new people, and share new sides of themselves.

We had a first-hand experience of how 90 minutes in a carefully-crafted space can help people learn to be more human. We’re so grateful you shared it with us!

Practioners Meeting (from Mack Stirling)

On the last day of the recent conference in Mexico City a group of about 20 mimetic practitioners met for a late lunch, carrying on the tradition begun last year in Paris. The group was enlivened by the presence of five young men, attending COV&R for the first time, from five separate countries: Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, Italy, and the US. They were particularly happy to have the opportunity for informal conversation at lunch outside of a conference session. We benefited greatly from the presence of Tony and Linda Bartlett, Scott Sherman, Debra Holden, and Martin Girard as we discussed ways that COV&R could better meet our needs as nonacademics—and ways that we could help in the dissemination of Girardian thought in our respective spheres. We will prepare a report for the COV&R board summarizing our discussion and look forward to continuing the “practitioners luncheon” in years to come.

Theology and Peace 2024 Conference

Ellen Corcella

The 2024 Theology and Peace Conference and Annual Meeting was held at the Casa Iskali Retreat Center, located just outside Chicago, Illinois from June 10 to June 13, 2024. The Conference theme, “Communicating God’s Non-Violent Love,” brought attendees from across the United States as well as virtual participants from as far away as New Zealand and Australia. The Conference participants were passionate about sharing the story of God’s unconditional love.

James Warren, the author of Compassion or Apocalypse: A Comprehensible Guide to the Thought of Rene Girard (2013), opened the conference with his concise and insightful review of the origins of Mimetic Theory. Fr. James Alison opened this plenary session with his brilliant undoing of sacrificial atonement, urging us to move beyond shame because Jesus intended not to short cut our way to forgiveness, but to “occup[y] the space of death and shame so as to detoxify those realities forever” ( https://jamesalison.com/catholicity-sacrifice-and-shame/ accessed August 7, 2024).

We moved from theory to explore effective means to shift from mimetic rivalry to loving mimesis. Rev. Adam Ericksen, pastor of Clackamas United Church of Christ, Milwaukie, OR, reminded us that the world needs to hear our voices and we can amplify our voices by using social media to spread the “scandalous” message that God’s love overcomes violence. Several of Pastor Adam’s congregants provided powerful testimony about discovering Pastor Adam online and undergoing a personal transformation from hearing and embracing the message of God’s love.

The Rev. Dr. Julia Robinson Moore, Associate Professor of Religious Studies at UNC, Charlotte, North Carolina and author of Race, Religion, and the Pulpit: Reverend Robert L. Bradby and the Making of Urban Detroit (2015), presented her current research entitled -Remembered: Enslaved Burial Grounds and the Making of the City of Charlotte. Working through the Equity in Memory and Memorial program, Dr. Moore seeks to heal racial trauma by reconnecting descendants of enslaved peoples with their white counterparts within Presbyterian churches throughout Charlotte. Dr. Moore uses a mind-body trauma informed process (www.ImmanualApproach.com) to facilitate racial reconciliation between community groups and implement an approach grounded in transformational love.

The Rev. Ellen Corcella, a palliative care chaplain for Eskenazi Health, a Trauma One Level Midwest hospital system, explored how we might embody God’s non-violent love in our interpersonal relationships positing a trauma informed paradigm combining Henri Nouwen’s concept of the “wounded healer,” Dr. Shelly Rambo’s theology of trauma and spirit, and Rebecca Adams’s concept of “loving mimesis.” Rev. Corcella then led participants in an analysis of a patient case study as an example of ways we can encourage movement from an interaction predicated upon fear and rivalry to an encounter that allows one to witness another’s suffering and uncover a shared human capacity to feel God’s love as one human being to another.

We held the Annual Meeting on June 13th, electing the following to the Board of Directors: Shannon Mullen, Rebecca Adams, Suella Gerber, Karen Kepner, Wesley Dunbar and Ellen Corcella. Tim Seitz will be an advisor to the Board and Andrew McCrae will continue to facilitate T&P’s popular program, Mimesis at the Movies. As to the future of T&P, we will continue our Quarterly Speaker Series starting again in September, 2024.

The Board was tasked with reviewing and providing a report on the resources of T&P and provide suggestions about programming as we move into the future. The enthusiasm for the work, camaraderie and messaging provided by T&P was expressed best by one new participant at the Annual Meeting who observed that this is a critical time to continue communicating the good news of God’s nonviolent love via the work of Theology & Peace.

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the Bulletin editor, Curtis Gruenler.

Mimetic Theory and Film

William E. Cain

Edited by Paolo Diego Bubbio and Chris Fleming

Violence, Desire, and the Sacred, Bloomsbury Academic, 2019 (cl), 2020 (pb)

ix + 211 pages

This collection of essays shows the powerful relevance of René Girard’s work for the study of film. As Paolo Diego Bubbio and Chris Fleming point out in their Introduction, Girard himself said little about film, and teachers and scholars influenced by him have mostly followed his lead, concentrating on literature, religion, anthropology, and other fields. There are exceptions: for example, some stimulating essays in Mimesis, Movies, and Media, volume 3 of Violence, Desire, and the Sacred, edited by Scott Cowdell, Chris Fleming, and Joel Hodge (2015), and David Humbert’s excellent monograph, Violence in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock (2017). But overall, when it comes to Girard and film, we’re at an early stage, and this collection for many will be a crucial point of departure and source of inspiration.

Mimetic Theory and Film opens with the editors’ reflections on the prospects for and implications of a Girardian “aesthetic” or “poetics” of “the moving image” (13). Ten essays follow, each of them rewarding.