Contents

Letter from the President, Martha Reineke

Editor’s Column, Curtis Gruenler

COV&R Annual Meeting at Purdue University, Lafayette, Indiana, USA

COV&R Sessions at the American Academy of Religion, Grant Kaplan

Australian Girard Seminar, Marie R. Joyce

Catholic Imagination Conference, Loyola University Chicago, Stephen McKenna

Nominate an artist for the Raven Award for Excellence in Arts and Entertainment

René Girard, Sacrifice, reviewed by Michael Kirwan

Letter from the President, Martha Reineke

Martha Reineke

University of Northern Iowa

In my first months as president of COV&R, I’m in a “getting to know you” phase with our partner organizations. Although most of these organizations are already familiar to COV&R members, I’ve realized that COV&R’s relationship could be more intentionally mimetic, and in a positive way! Who are we when viewed from the vantage point of these organizations? How can we get to know our partners better? In this issue of the Bulletin, I’m sharing features of a recent interview that I conducted with COV&R board member Suzanne Ross, the head of one of our partner organizations: The Raven Foundation. In future issues, I plan to share summaries from interviews with representative voices from our other partner organizations.

I asked Suzanne for her recollections of how our partnership with Raven came about. She told me that, from beginning, husband Keith Ross, with whom she founded the foundation, and she have felt that Raven is an offspring of COV&R. Everything Keith and Suzanne learned from COV&R conferences and books, they wanted to share and bring to a non-academic audience. Initially, they didn’t think of themselves as “partners” to COV&R. That relationship has evolved over the years as they have made financial contributions to conferences and speakers. It has been “a source of joy” to be supportive of COV&R, says Suzanne.

I asked Suzanne what she would most want COV&R members unfamiliar with Raven to notice about the foundation. Suzanne said she would want us to know how Keith and she have been profoundly affected in a personal way by mimetic theory. When they engaged mimetic theory at their church, their faith was changed and enlivened. That personal impact motivated them to learn more, to grow, and to be supportive of scholarship on mimetic theory. All the members of the “Raven flock” tell the same story: mimetic theory has brought them closer to God, enhanced their faith, and enabled them to have healthier relationships with each other and with the world at large.

When I asked Suzanne how she would describe COV&R to someone unfamiliar with our organization, Suzanne said that she would depict COV&R as “an academic organization and group of scholars dedicated to research applying mimetic theory across disciplines.” She would emphasize how its interdisciplinary nature and openness to non-academics and nonmember participants is unusual and contributes to a high degree of collaboration among its members.

Suzanne expressed that the most positive aspects of the partnership of COV&R with Raven has been “their access to amazing scholars who treat you as friends and as equal partners.” She finds what we do “very exciting” and loves reading the books published by our scholars of mimetic theory. “Bringing those ideas out into the world is so important.” Indeed, for Suzanne, COV&R has made Raven’s work possible: “COV&R is part of Raven’s DNA. I can’t imagine Raven without COV&R.”

I asked Suzanne to share with me from her perspective as an appreciative partner, what she sees as potential growth areas for COV&R. She suggested that we may want to explore ways to include more non-academics in our conferences. More content directed at non-academics might be attractive. The content could emphasize how mimetic theory makes a direct difference in peoples’ lives: “Applied mimetic theory” could be a way of framing this content. We also could explore how we might be able to offer continuing education credit hours as a way of supporting professional engagement by non-academics with our conferences. Suzanne also identifies as a strength to build on our ability to reach out, on occasion, to the local community in our conference host city to include nonacademics with interests in applied mimetic theory in our conferences. Preconference workshops that would introduce non-academics to mimetic theory along the lines of our opening sessions (Mimetic Theory 101) also might expand conference participation in exciting new ways.

As for the Raven Foundation, their current goals include reorienting their mission around new website, developing a new newsletter, and using more media to get their message out. They are working with video and audio editors to explore new communication formats and to add new voices to their outreach.

Just as Suzanne can’t imagine Raven without COV&R, I can’t imagine COV&R without Raven. Keith and Suzanne’s enthusiasm for our organization and their support (financial, inspirational, and creative) are an extremely positive influence on COV&R. We cherish all members of the Raven flock and are immensely grateful for Keith and Suzanne’s partnership with COV&R as together we draw on mimetic theory to illuminate the most pressing issues of our day and promote peaceful transformation interpersonally, in our communities, and on a national and global scale.

Editor’s Column

Publication News

Curtis Gruenler

Hope College

Members (except for those who joined recently) should have received earlier this fall Nidesh Lawtoo’s (New) Fascism: Contagion, Community, Myth from the Michigan State University Press series Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory.The Oedipus Casebook: Reading Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, edited by Mark Anspach, is scheduled to be published by the end of the year. Consider soliciting a review from your friendly neighborhood classicist for their favorite journal. Next year will bring Giuseppe Fornari’s long-awaited, two-volume Dionysus, Christ, and the Death of God: volume 1, The Great Mediations of the Classical World, and volume 2, Christianity and Modernity.

Members (except for those who joined recently) should have received earlier this fall Nidesh Lawtoo’s (New) Fascism: Contagion, Community, Myth from the Michigan State University Press series Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory.The Oedipus Casebook: Reading Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, edited by Mark Anspach, is scheduled to be published by the end of the year. Consider soliciting a review from your friendly neighborhood classicist for their favorite journal. Next year will bring Giuseppe Fornari’s long-awaited, two-volume Dionysus, Christ, and the Death of God: volume 1, The Great Mediations of the Classical World, and volume 2, Christianity and Modernity.

We have added a new page to the COV&R website under the Publications tab called “Member Articles“. As the introduction to the page explains, this is a place for short (800-1,500 word) articles applying mimetic theory to topics of current interest. The idea arose because the Raven Foundation has recently refocused its mission (see Martha Reineke’s interview with Suzanne Ross above) so that some of the old website’s content no longer has a place, but I wanted to make two movie reviews they had published accessible for my students and for citation in an article. If there is other content from Raven or elsewhere that is no longer available but you would like to see added here, please let me know and we will see what we can do. We also invite members to submit new items for publication here. This page will be openly available and can be a home for items that do not fit either the internal communications mission of the Bulletin or the more academic mission of Contagion.

Forum Philosophicum, an “international journal for philosophy” published bi-annually under the auspices of the Jesuit University Ignatianum in Krakow, has published a theme issue on the topic “Mimetic Wisdom: René Girard and the Task of Christian Philosophy.” It features articles by Eric Gans, Anthony W. Bartlett, Bernard Perret, John Ranieri, Stefano Tomalleri, Charles Mabee, Emanuele Antonelli, Maria Korusiewicz, and Thomas Ryba.

From Anthropology to Social Theory: Rethinking the Social Sciences by Arpad Szakolczai and Bjørn Thomassen (Cambridge University Press, 2019), affirms the importance of René Girard among the “maverick anthropologists” who it argues have been unwisely marginalized in the development of mainstream academic social theory, especially in anthropology and sociology. Girard is treated alongside the work of Gabriel Tarde on imitation, which, along with Arnold von Gennep and Victor Turner on liminality, Marcel Mauss on gift-giving, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl and Colin Turnbull on participation, Paul Radin on the trickster, and Gregory Bateson and John Huizinga on play, provide what the authors argue is an essential toolkit for understanding sociology and modernity. Their discussions of each thinker are fascinating, and even more their suggestions of how the tools in the kit work together: how liminality and the trickster unfold the effects of scapegoating dynamics, or how gift-giving, play, and participation supplement mimetic rivalry in the direction of what Girardians might call positive mimesis. I am not competent enough in anthropology to attempt a full review, but the Bulletin would welcome one from someone more at home in these waters. If you are interested, please contact our book review editor, Matt Packer.

Forthcoming Event

COV&R Annual Meeting 2020:

Desiring Machines: Robots, Mimesis, and Violence in the Age of AI

Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, July 8-11

Thomas Ryba and I are delighted to invite the COV&R community to Purdue University, from July 8 to 11 of 2020, where we will convene the COV&R 2020 conference entitled Desiring Machines: Robots, Mimesis, and Violence in the Age of AI. We feel that with the burgeoning importance of the field of artificial intelligence worldwide, it is incumbent upon those of us interested in Girardian thinking to explore relations between AI and mimetic theory. Invitees will include members of COV&R and experts in the field locally and internationally. We invite papers that probe these relations from a wide variety of disciplines but especially from Girardian perspectives and we urge potential attendees to consult the “Call for Papers” published on the COV&R website and soon to be available on the upcoming Purdue website. For further information, please contact me via email. -Sandor Goodhart.

Conference Reports

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion

A Summary

Grant Kaplan

St. Louis University

In late November, scholars of religion and theology descended on San Diego from all corners of the globe for their annual conference, which attracts roughly 10,000 attendees. Among this multitude were members and friends of the Colloquium on Violence & Religion. COV&R is a Related Scholarly Organization, which means that it hosts sessions under the tent of the American Academy of Religion without being an official group.

This year COV&R hosted two sessions. The first took up the theme: “Girard the Provocateur: Exploring Mimetic Escalation in Dangerous Times.” It met on Saturday morning, and included papers by Charles Bellinger, Artur Rosman, and Kevin Hughes, and yours truly moderated the panel. Bellinger discussed the “Kierkegaard-Girard Option,” which he compared and contrasted to Rod Dreher’s “Benedict Option.” Rather than retreat into enclaves, as Dreher suggests, Bellinger recommends forming habits and practices that will enable people to have better conversations across disciplines. He gave the example of “rights talk,” in which disagreeing parties often appeal to rights without any understanding of the history and genealogy of the term. Bellinger then mentioned that secondary education almost never deals with violence as a topic of education, but that such a topic would equip students of all stripes for confronting violence and understanding its roots.

Rosman discussed Emmanuel Carrère’s novel, The Kingdom, and the mimetic themes in it. This novel-as-memoir discusses Carrère’s de-conversion from Christianity—in particular, a very intense form of Catholicism. At the heart of Carrère’s issues with his own, prior Christianity was an intellectualized faith in which his heart was unchanged (one could contrast this with Lonergan’s understanding of “religious conversion” as the pouring of the Holy Spirit into our hearts [Rom 5:5]; thus, one could say that Carrère was never religiously converted). Rosman discussed the deep ambiguity at the end of The Kingdom, about whether the de-converted hero was in fact closer to Christianity than the formerly-practicing hero of the novel. Rosman ended by noting that the novelist does not have the final say about the meaning of his work. This final say belongs to the critic and biographer, and at this point Rosman noted how Girard saw his novelists, especially Proust, as religiously converted, even though Proust would have only been a Christian in a loose sense.

Kevin Hughes discussed the scandal over Carrère’s The Kingdom that erupted at Franciscan University, a conservative Catholic institution of higher education, where the novel had been taught by a faculty member, Stephen Lewis. Hughes detailed how a far-right quasi-Catholic news website reported that Lewis was teaching pornographic literature about the Virgin Mary at a university that purported to be a refuge from such activities. The scandal led to the ousting of the president of Franciscan, and the (unsuccessful) call for Lewis to be fired; Lewis was instead relieved of his chairmanship of the English department. Hughes connected this episode to other academic escalations, and noted how the pattern of ascending escalation at Franciscan University mirrored patterns at places like Yale and other more mainstream and liberal universities that would want to be nothing at all like Franciscan. Hughes then integrated an off-Broadway play, “Heroes of the Fourth Turning,” into his discussion of escalation and scapegoating. The play, by Will Arbery, discusses the lives of four recent alumni of a fringe-conservative Catholic institution not unlike Franciscan, and points out that, even after the Trump election, conservatives, like liberals, find themselves in a battle over a shrinking turf, in which it is impossible not to feel like one’s side is losing. It is in this context that so much toxicity in higher education smolders, and ensures that deeper engagement with mimetic theory will be instructive if not imperative for higher education’s survival.

The second panel included four papers discussing the recently-published collection, Mimesis and Sacrifice: Applying Girard’s Mimetic Theory across the Disciplines (ed. Marcia Pally). The four panelists represented four of the fourteen chapters in the book. A fifth panelist, Marcia Pally, was unable to attend. These panelists offered summaries of their chapters. The first, Anna Mercedes, gave a paper titled, “Does Christ Resist or Bow Out: Feminist Theology, Violence, and René Girard.” The second, Wolfgang Palaver, read “Sacrifice Between West and East: René Girard, Simone Weil, and Mahatma Gandhi on Violence and Non-Violence.” The third, David Pan, discussed “Immanuel Kant on Sacrifice and Morality,” while the final panelist, Ilia Delio, read “Suffering and Sacrifice in an Unfinished Universe: A Challenge for ‘Techno-sapiens,’” which took up the thought of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit paleontologist and expositor on the noosphere. It was refreshing and confirming to hear mimetic theory brought into conversation with thinkers like Gandhi, Kant, Hobbes, and Teilhard. A greater summary is omitted since those interested can consult the book.

Rich discussion followed both panels, and various ideas were floated in the business meeting, including a panel on feminist theology and mimetic theory, and revisiting the application of mimetic theory to Christian spirituality. Bill Johnsen once again occupied the table devoted to the series on mimetic theory with Michigan State University Press at the massive book fair. The conference presented a great opportunity to renew acquaintances with old friends and to see new faces interested in mimetic theory. On to Purdue!

Seminar on Current Girardian Scholarship in Australia

Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, Victoria, and Brisbane, Queensland

Marie R. Joyce

Australian Psychological Society

On Friday, 11 October, 2019 scholars and readers of Girard gathered for a video conference at campuses of Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, Victoria, and Brisbane, Queensland, with 14 and five attendees at each campus respectively. Most were members of Girardian reading groups which meet monthly to study and discuss the works of Girard.

On Friday, 11 October, 2019 scholars and readers of Girard gathered for a video conference at campuses of Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, Victoria, and Brisbane, Queensland, with 14 and five attendees at each campus respectively. Most were members of Girardian reading groups which meet monthly to study and discuss the works of Girard.

Following a brief introduction to Girard’s thought by Joel Hodge, there were two presentations: “Girard, Gender and the Hebrew Bible,” by Rena MacLeod in Brisbane, as a culmination of her Ph.D. research, and “Violence in the Name of God: The Militant Jihadist Response to Modernity,” by Joel Hodge, drawing on his upcoming publication of the same title.

Girard, Gender and the Hebrew Bible

Rena’s presentation brought together Girardian mimetic theory and feminist theory with a view to examining women victims within biblical narratives. She maintained that Girard has clearly highlighted the vulnerability of women to scapegoating in male-centred/androcentric societies, though exploration of the biblical representation of this has been lacking. She acknowledged that mimetic theory holds numerous strengths for analyzing biblical texts of persecuted women, given that it employs a hermeneutic of suspicion and highlights the importance of victims as disclosing patterns and processes of scapegoating. However, Rena argued mimetic theory is limited in its capacity to explain women’s marked scapegoat location in androcentric texts and contexts because it does not take detailed account of how men’s and women’s distinctive socialization into androcentric cultures shapes desire, rivalry and violence in gendered ways. Rena proposed an interpretive model that combined mimetic and feminist theory concepts to enable greater analysis of gendered experiences of scapegoating in texts of persecution.

Rena took as a case study the Book of Judges from the Hebrew Bible. Via her proposed interpretive model, she illustrated how this corpus may be read as emphasizing that the primary rivals of men in androcentric societies are other males, and, as men pursue their desires to embody the characteristics of dominant masculinity, they become both the overwhelming perpetrators and victims of men’s violence. She further highlighted Judges’ disclosure of women as distinctive scapegoat figures within contexts of male aggression whose victimization serves to channel and ameliorate men’s violence. Rena put forward the idea that these texts challenge contemporary readers to move beyond enduring androcentric myths, which socialize men as superior to women, and instill the belief that performing violence is an acceptable characteristic of normative masculinity.

Violence in the Name of God: The Militant Jihadist Response to Modernity

In his analysis of Islamist Jihadism, Joel identified the victim discourse that jihadists use to justify their violence: “You think we are the aggressors …. we are victims” (Dr. Abdul Aziz Rantisi, a founder of Hamas, in Mark Juergensmeyer, Terror in the Mind of God [Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000], 74). He noted at the outset too that most jihadist violence is perpetrated by males, but that there is also a significant component of female involvement in and support of violence in jihadist groups. The rhetoric of militant jihadist groups focuses on fighting “infidels”; giving back what is due to the Islamic world; acts of “service,” protecting Muslims and the religion of Allah, linking jihadism, self-sacrifice and martyrdom; and perpetuating an apocalyptic discourse of violence in the name of justice. Their explicit and violent targeting of victims is celebrated as sacred violence through the attribution of transcendent qualities to their violence. In their system, Islamic renewal necessitates jihadism.

Joel traced the roots of their re-sacralizing of violence as a response to modernity through the development of a historical narrative embracing events from the fall of the Caliphate in 1924, through widespread experiences of colonialism and the rise of Islamization in 1970s, along with regional and global identities expressed in Islamist movements. Wars and the breakdown of cultural institutions in the decades since have further enhanced their movements. Joel argued that although violence cannot be sacralized in the way it was in traditional cultures because scapegoating has lost its power, jihadists nevertheless try to resuscitate the sacred power of violence and go to extremes in their attempts to achieve this. They attribute absolute transcendence to their violence so that such violence is not the responsibility of the mob, but rather, is commissioned by the Abrahamic God. In this way, they distort the Abrahamic God in the name of the victims and attempt to reverse the movements of the Abrahamic traditions which have sought to reveal human violence and a non-violent God. Thus, militant jihadism is an intentional perversion of that which revealed violence.

We congratulate Rena and Joel on their presentations, which were followed by lively question and discussion sessions. We look forward to Joel’s forthcoming book Violence in the Name of God: The Militant Jihadist Response to Modernity (Bloomsbury, 2020), and hope to see Rena’s work in publication soon.

Girard Session at the Catholic Imagination Conference

Loyola University, Chicago

Stephen McKenna

Speech and Writing Consultant

The roster of plenary speakers and panels at the third biennial Catholic Imagination Conference, hosted at Loyola University of Chicago’s Hank Center September 18-21, 2019, including such American writers as Dana Gioa, Fanny Howe, Alice McDermott, Richard Rodriquez, Paul Schrader, and Tobias Wolfe, was an embarrassment of riches. A stage version of Flannery O’Connor’s “Everything that Rises Must Converge” (created and directed by Karen Coonrod and Angela Alaimo O’Donnell) and the premier of the documentary Flannery were especially rich experiences. (Created by filmmakers Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco, S.J., Flannery has since won two major awards: the Library of Congress’s inaugural Levine/Ken Burns Prize, and the Austin Film Festival’s award for Best Feature Documentary.)

(L to R) Andrew McKenna, Cynthia Haven, Colby Dickinson – presenters

Of particular interest to COV&R members was a panel moderated by The Raven Foundation’s Suzanne Ross, entitled “As Satan Falls: René Girard and the Mystery of Paying Attention,” with presentations by Andrew McKenna, Colby Dickinson (both of Loyola University of Chicago), and NEH Public Scholar, writer, and Girard biographer Cynthia Haven. The focus of the panel was to visit anew how Girard’s thought “anticipated the present moment and serves as a prophetic voice for the ‘futures’ of Catholic thought, practice, and artistic representation.”

For those perhaps somewhat wearied by Girardians’ regularly frequented canon of literary artists—Dostoyevsky, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Flannery O’Connor, Cormac McCarthy and so on—Andrew McKenna’s presentation looked at an author rather less commonly addressed by mimetic theorists: Flaubert—a writer who, unlike those Catholic artists, “made a religion of literature, and who knows it’s a god who fails.” Nevertheless, in Flaubert, as with all great literary artists, McKenna finds that “Catholic” hallmark of the incarnational that Girard likewise attended to in his close readings. McKenna took up the late story A Simple Heart (Un Coeur Simple), which centers on the ironically named Felicity, an aged, uneducated, guileless house servant losing her sight and hearing, whose life has been little more than a series of tragic losses, but who nevertheless finds not just temporal consolation in her rotting, taxidermied parrot—a mimetic symbol par excellence—but ultimately a transcendent experience of the Holy Spirit. (Flaubert had actually himself purchased a stuffed parrot so as to get into the psyche of his character.) While Flaubert was a staunch unbeliever, neither could he accept any of the pseudo-secular, enlightened substitutes for religion: not the “mimetic addiction to received ideas,” nor the “enlightened” bourgeois belief in “progress,” nor the Arnoldian replacement, Art. And yet, argued McKenna, even though “Flaubert does not believe as Felicity does, or what she believes… he thoroughly believes in her belief, in its simple goodness.” Here McKenna divined exactly that Catholic imagination wherein contemplation, meditation, and reflective absorption—Felicity’s in the parrot, Flaubert’s in Felicity, and ours in Flaubert—take the form of the rapt attention that Simone Weil held to be nothing if not a form of prayer. One upshot of this, concluded McKenna, is that the Catholic imagination is too important to be left only to believers.

Cynthia Haven followed with presentation particularly helpful for orienting non-Girardians to mimetic theory. She began with a comment on two recent mass shootings in the US earlier this year. On August 3, in El Paso, Texas, 22 people were slain by a white nationalist targeting Latinos; hours later, a man killed 9 people in Dayton, Ohio. The initial assumption by many, that the Dayton shooter held prejudices similar to those of the El Paso shooter, evaporated when it was discovered he self-identified as a “pro-Satan” leftist supporter of Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren. While this obviously didn’t fit the common media narrative, Haven pointed out, there was a pattern: the Dayton shooter had been following events in El Paso and was long fascinated with mass killings. (Haven could have added that the El Paso shooter was likewise an admirer of the Christchurch mosque massacre that killed 51 people.) Facts about the Dayton killer pointed instead to a host of cultural and social factors inflamed in the media, which, “in the age of Facebook and Twitter, is all of us.” The question of our complicity in the baleful effects of mimesis is essential. While interpreting texts and events can be useful for exploring how mimesis, rivalry, violence, and scapegoating operate, the most important place to verify mimetic theory, said Haven, is in our own hearts.

Cynthia Haven followed with presentation particularly helpful for orienting non-Girardians to mimetic theory. She began with a comment on two recent mass shootings in the US earlier this year. On August 3, in El Paso, Texas, 22 people were slain by a white nationalist targeting Latinos; hours later, a man killed 9 people in Dayton, Ohio. The initial assumption by many, that the Dayton shooter held prejudices similar to those of the El Paso shooter, evaporated when it was discovered he self-identified as a “pro-Satan” leftist supporter of Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren. While this obviously didn’t fit the common media narrative, Haven pointed out, there was a pattern: the Dayton shooter had been following events in El Paso and was long fascinated with mass killings. (Haven could have added that the El Paso shooter was likewise an admirer of the Christchurch mosque massacre that killed 51 people.) Facts about the Dayton killer pointed instead to a host of cultural and social factors inflamed in the media, which, “in the age of Facebook and Twitter, is all of us.” The question of our complicity in the baleful effects of mimesis is essential. While interpreting texts and events can be useful for exploring how mimesis, rivalry, violence, and scapegoating operate, the most important place to verify mimetic theory, said Haven, is in our own hearts.

After a lucid and compact precis of mimetic theory, from simple imitation to the emergence of sacrificial order predicated on a founding murder, Haven returned to this question, noting how the digital social environment seems to accelerate and widen contagion and complicity in ways hardly imaginable just a short time ago. The stakes are not just for how we treat others: “We dismiss our daily defamations as harmless, but they are not, primarily because it changes us.” If we are to avoid this, we must commit to a radical path. As Girard writes in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World: “[W]e must see that there is no possible compromise between killing and being killed…. If all men loved their enemies, there would be no more enemies…. There is no other cause of [Jesus’] death than the love of one’s neighbor lived to the very end with an infinitely intelligent grasp of the constraints it imposes.”

Haven urged that we each need to reckon with the “constraints” in the midst of our ongoing addictions to archaic sacrificiality, because we can no longer claim innocence, and the vortex of bad mimesis is formidable (especially in an age of digital inattention). People even cite Girard in defense of their prejudices, blind to how mimetic theory is a critique of precisely that impulse. The imperatives of forgiveness and reconciliation, so central the Catholic imagination, are the only antidote to becoming the kind of people who are the engines for violence and scapegoating. Forgiveness is liberal: it frees us. Among other things, said Haven, it frees us to pay attention to and love others, all others, even those caught in their own mimetic pathologies, however severe. Mass shooters. White supremacists. ISIS members. Haven ended quoting Girard’s last lines of The Scapegoat: “We must face our neighbors and declare unconditional peace. Even if we are provoked, challenged, we must give up violence, once and for all.”

Colby Dickenson’s presentation further mined exactly what this radical solution must mean, and what it might look like. He began his talk with a provocative set of questions prompted by Giorgio Agamben’s argument that humanity must engage in “absolute profanation” in order to restore any of what had once been understood as sacred. Slavoj Žižek’s response to Agamben—that such a profanation would likely be the new degree zero for the sacred—prompted Dickenson to ask whether such a removal may be not only the way to recover the sacred, “but this time, [to do so] for real.” Dickenson noted how his set of problems is mirrored to some degree in John Milbank’s critique of Girard as essentially a nihilist, because the project of mimetic theory is similarly negative: to uncover the scapegoat mechanism in all its manifestations, yet without conceiving of a socially just order to restructure whatever is left after such apocalypse. Does the endless imperative to identify and defuse the mechanism leave us time or energy or resources for the attention needed to create a peaceful world that acknowledges the sacred nature of existence?

This question about the economy of attention and interruption points to the problem of how to contend with historical metanarratives. Following Gianni Vattimo, Dickenson argued that they cannot be countered by other metanarratives but only by a postmodern “weak historicism” that, by denying the priority of a center holding together stable principles and values, allows discrete events their own interpretive ambit. In a way that harmonizes with Girard, Vattimo likewise asserts that this was once precisely the role of Christianity: to confess the way a particular event exposes archaic religiosities once and for all, giving meaning to true religion. While it is potentially problematic, noted Dickenson, because it is up against the fact that other nihilisms are at the core of the sacrificial religiosities of our contemporary world, it appears to be the only and essential path for humanity. Dickenson noted how Vattimo’s claim also resonates with the negative dialectics of Adorno, which called for a “dissolution” of dialectics, dialectics being “deeply complicitous with the alienation it intends to control,” and also with Johann Metz’s contention that religion is simply “interruption.” As such, the role for theology (and, we might ask, the Catholic imagination?) is only to “keep open the possibility of an interruptive event, not to foreclose such an event forever through its transformation into a lasting (static or dynamic) tradition.” The role for love must likewise be mystical and attentive; in that way, it bears affinity to the deity who is outside all moral and institutional orders, is the basis for those orders, yet is not of them. The thing to replace religiosity of the false sacred, concluded Dickenson, is just such a love: love in a register that may be an “absolute profanation”—an eventful action unafraid to lose traditional moral order(s), “so that something truly sacred might appear.”

It was a deeply stimulating set of presentations that yielded vigorous discussion. Video from plenary sessions of the 2019 Catholic Imagination Conference are available here. In December, the breakout session videos can be accessed through the conference website.

Letter from…Sydney

“When Gods Walked the Earth” Art Exhibition by Mauro De Giorgi Devoted to Mimetic Theory

Paolo Diego Bubbio

Western Sydney University

In 2017, in the final stages of the production of my book Intellectual Sacrifice and Other Mimetic Paradoxes (an account of my twenty-year intellectual journey through mimetic theory), I was asked to pick a picture for the book cover. In a flash of inspiration, I contacted my old friend Mauro De Giorgi, an Italian-born, internationally renowned artist. I asked Mauro if I could borrow one of his artworks for the cover of my book. Mauro liked the idea, but wanted to read my manuscript first.

In 2017, in the final stages of the production of my book Intellectual Sacrifice and Other Mimetic Paradoxes (an account of my twenty-year intellectual journey through mimetic theory), I was asked to pick a picture for the book cover. In a flash of inspiration, I contacted my old friend Mauro De Giorgi, an Italian-born, internationally renowned artist. I asked Mauro if I could borrow one of his artworks for the cover of my book. Mauro liked the idea, but wanted to read my manuscript first.

He called me one week later, and he had a thrill in his voice. One week earlier, he barely knew the name of René Girard. A week later, he had become so intrigued by mimetic theory that, after reading my manuscript, he had rushed to read Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World.

This story wouldn’t be so original—we have all heard, if not experienced ourselves, stories of people being stricken by mimetic theory “on the road to Damascus”—if it ended here. But it didn’t (does it ever?). Was Mauro willing to offer one of his artworks for my book? Sure he was. But he wanted to do more than that—he wanted to create a series of artworks entirely devoted to mimetic theory.

And so he did. The resulting artworks were beautiful, meaningful, and impactful. A few months later, we were talking about the possibility of organizing the first art exhibition entirely devoted to mimetic theory. We approached the Raven Foundation for financial support, and their response was enthusiastically positive. The venue was provided by the Italian Cultural Institute in Sydney (a beautiful historic building in the center of Sydney), and the event was supported by the Philosophy Research Initiative at Western Sydney University. The friends of the Australian Girard Seminar helped in the promotion of the event. I was asked to be the curator of the exhibition, and it has been an amazing experience.

The exhibition “When the Gods Walked the Earth” opened on October 10, receiving some significant media attention (interviews with ABC Radio National and other networks, articles in online and local newspaper and art publications, etc.) and attracting a large audience.

By now, you might be curious to know something more about the artist and the exhibition, and I’ll try to satisfy your curiosity (although I can only do so in the briefest of ways).

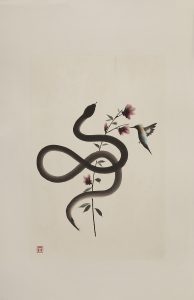

Mauro De Giorgi (Torino, 1972) has been always fascinated by Asian and Japanese aesthetics. He exhibited in Italy (Venice Biennale), United Kingdom (at various London galleries), Japan (Tokyo), Singapore, and France. De Giorgi’s style is unique: he creates contemporary art which combines Asian, Japanese aesthetics and techniques with Western (and sometimes specifically Italian Renaissance-inspired) themes and insights.

Why this combination? It would be easy to answer that the Japanese Edo period bears similarities with the Italian Renaissance as they both seek to unveil the mysterious beauty of nature; or that he found in the traditional Japanese techniques (sumi, gyotaku, ukiyo-e) the thrill of an exotic taste that has the potential to generate a short circuit in our (often exhausted) Western aesthetics.

These might be good reasons, but they would miss the point. At the core of De Giorgi’s aesthetics, there is the sharp refusal of a desperate search for modernity and “spontaneity.” It is significant that, to introduce his work, De Giorgi often quotes Rimbaud’s claim “Il faut être absolument moderne! [one must be absolutely modern!]”, adding that he, De Giorgi, couldn’t disagree more. So, the encounter between De Giorgi’s art and Girard’s mimetic theory, however serendipitous it might have been, was in a sense inevitable (we know that no one is more “mimetic” than someone who wants to reclaim for him/herself an impossible spontaneity and originality). De Giorgi is an artist “of the origins”: everything in his art – from the topic to the techniques – screams the need to “go back” and retrieve ancient meanings.

In a whirlwind of evocative and moving images, De Giorgi’s artworks make us travel from the abstract mimeticism of “Father and Son” and “Mimetic Desire,” through the myths evoked in “Medusa and the Double” and the iconic character of Oedipus, the powerful “Scapegoat,” up to the Christian symbolism of “Dancing Salome,” “The Demons of Gerasa,” and “The Last Supper”—and finally to the iconic “Mimetic Allegory.” And through the aesthetic experience that is gifted to us, we can meditate on our own deeply mimetic nature, and on the imperative need to reject scapegoating and violence.

The exhibition will remain open until March 27, 2020, at the Italian Cultural Institute (125 York St., Level 4). If you happen to travel to Sydney, don’t forget to stop by!

Nominate an artist for the Raven Award for Excellence in Arts and Entertainment

The Raven Foundation is currently accepting nominations for the Raven Award! This year, we are looking for artists and entertainers whose work exposes myths about violence and the false promise that it can bring peace.

The Raven Foundation is currently accepting nominations for the Raven Award! This year, we are looking for artists and entertainers whose work exposes myths about violence and the false promise that it can bring peace.

If you know someone whose work deals creatively with these themes, please nominate them by clicking here, scrolling to the bottom of the page, and filling out the submission form.

The winner will receive $2500 and an original award crafted by a local artist! Nominations close on December 1, 2019 at midnight CST (GMT -6).

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the book review editor, Matthew Packer.

Girard on Hindu and Buddhist Texts

Michael Kirwan SJ

Trinity College

René Girard, Sacrifice. Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory. East Lansing: Michigan State UP, 2011 (French original, 2003). Translated by Matthew Pattillo and David Dawson. Pages xii, 103.

This short but important text interweaves a lucid presentation of René Girard’s mimetic theory with selected readings from the Brahmanas of Vedic India. Girard finds in these texts confirming evidence of his insights regarding the exclusionary nature of sacrificial ritual. First delivered as a series of lectures at the National Library of France in 2002, Sacrifice can be considered a “Breakthrough in Mimetic Theory” for its venturing beyond the Jewish and Christian scriptures. In accordance with the theory’s predictive power as an anthropology, we should expect to find analogous structures and processes analogous to those found with the Hebrew Testament and the Gospels.

Such a quest, as Girard points out, runs counter to the spirit of religious inquiry for much of the twentieth century. Even the possibility of such connections is ruled out, for fear of ethnocentrist and even supremacist lapses. The book opens, therefore, with a four-page preface from Girard, repeating (in more succinct form) the methodological apologia which appeared at the beginning of Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978). Then, and again here, Girard castigates researchers for their holophobic lack of ambition:

It is not excessive ambition that threatens us now, but bureaucratization and provincialization as research is more and more limited to the local and the particular. Once the great questions are discredited, for want of intellectual stimulation anthropology languishes. Still quite lively in the era of Durkheim and the early Levi-Strauss, the discipline has since tended to settle into a rather disappointing routine. (3)

If anything, Girard is even more caustic in this later text about the “dogmatic nihilism”—the “snobbery of the void”—which has hampered academic progress in recent decades. In view of this paralysis, Girard is justified in the recovery of earlier wisdom: from anthropology in its infancy, from Plato, and from ancient religious texts.

Girard’s turn to the Vedic scriptures is not as audacious as it sounds. Such a venture, he acknowledges, would be “imprudent” (10), but he makes clear he is working from one text by a western author, Sylvain Lévi’s La Doctrine du sacrifice dans les Bramanas (1898, reprinted in 1966). This is a selective anthology of Brahamanic texts, from which Girard is able to discern the lineaments of mimetic processes.

In effect, therefore, he is reading Lévi’s anthology as simply another text, to be given the same treatment as Girard’s favoured literary writers (Cervantes, Flaubert, Dostoyevsky etc.), and according to the same criterion: these are writers who are obsessed, like Girard, with the paradox of violence, corrosive of the very difference it is intended to assert. If texts do not deal with this obsession, claimed Girard nonchalantly, “I leave them alone.”

In short, Sacrifice is not a direct and systematic engagement with the sacred traditions of Hinduism and should not be critiqued as such.

Also disarming, and no doubt frustrating for Girard’s critics, is his reiteration of one elegant aspect of mimetic theory. Because “many sacrificial systems make a point of minimising their own violence,” resorting to manoeuvres of disguise or displacement, the evidence for the existence of such violence is ambiguous. A “minimum of illusion” is required for sacrifice to be effective. The stories considered by Girard (courtesy of Lévi) display both manifestations of violence and hints as to its concealment. Both are, equally, confirmations of mimetic theory—therefore depriving its critics of any chance to land a killer punch.

Worth noting, here, is Girard’s fleeting reference to the debate about sacrifice and Christianity which had flared around his declaration, in Things Hidden, that “sacrifice” had no place in the Christian lexicon. This was because of its fundamental reducibility to exclusionary violence. Girard conceded—eventually—that the term could indeed be applied to Jesus, but his main argument remains unaffected: “If the term sacrifice is used for the death of Jesus, it is in a sense absolutely contrary to the archaic sense” (xi). Jesus’ “sacrificial” death reveals and disempowers the lie of blood sacrifice. In the gospels, “[t]he revelation and repudiation of sacrifice go hand in hand, and all of this is found, up to a certain point, in the Vedanta and in the Buddhist refusal of sacrifices” (ibid.).

Girard appreciates the “perspicacity” and “intellectual power” of the writers of the great Vedic texts, which—to use his own literary terminology—display both “romantic” and “novelistic” characteristics. That is, some of the stories simply depict or imply the mimetic sequence of rivalrous desire, crisis, and violent resolution; while elsewhere, the narrator “sees through” this sequence, displaying an awareness of and a critical distance from it.

Examples of the first include the narratives of the Devas and the Asuras (gods and demons), repeatedly drawn into conflicts over coveted objects—conflicts which are repeatedly if temporarily resolved by sacrifices. The founding narrative contained in the tenth and final book of the Rig Veda, the Hymn to Purusha, is the most significant such depiction, telling of the dismemberment of Purusha as a sacrificial quartering: the origin of the four varnas, and the hierarchy which ensues of priest, warrior, artisan, and servant. Despite the comparative serenity of this account, Girard notes the striking resonance with the frenzied diasparagmos of the Dionysian legends.

On the other hand, a process of demystification begins which comes to fruition at the end of the Vedic period, and in the critiques of sacrifice we find ultimately in Buddhism and in the Upanishads. Girard cites the perplexing hints in texts relating to the preparation of the sacrificial beverage, soma, and the sacrifice of the god of the same name (56-9). These point to a high degree of awareness of the function of sacrifice: as a strategy for preventing enemies from killing one another, by the furnishing of alternative victims.

An even greater distance from sacrifice is contained in two other texts, each with darkly comic elements. The first is the lampooning of sacrificial piety in the story of Manu, the primordial man (as discussed in Lévi); secondly, a Buddhist story concerning a Braman who attempts to abuse his ritual authority as the king’s sacrificer so as to destroy his wife’s lover (94). The hyperbolic ritualistic excess in the Manu legend resonates with the critique of the Old Testament prophets, such as Micah; sacrificial seriousness is similarly undercut by the dark comedy of the Brahman, whose scheming results in his own destruction.

Indeed, at various points in Sacrifice Girard shows a healthy liberationist suspicion of Brahmanic self-interest, given their lucrative role as the custodians of sacrificial rituals.

As Girard declares in the final chapter of the book, “[s]acrifices differ”—but not so much as to justify total relativism or the writing off of religion. His discussion of “resemblances” between myths and gospels (65) reads as a softening from his earlier work, where these two categories were mutually incompatible. In the same way, in Battling to the End, Girard hinted at a rapprochement between the previously opposed “Dionysus versus the Crucified.” The linking factor which makes comparison possible is violent mimeticism; the difference lies in the degree of enlightenment: “Mimeticism is essential to myths as well, but it has to be deduced from indirect clues, and its action must be surmised. In the Gospels it is manifest, brilliant” (71).

Frustratingly, however, Girard reverts to the tone of his earlier work when he asserts: “Judaism and Christianity are radically different from myths because they alone reveal a phenomenon whose existence myths do not even suspect, not because they are unfamiliar with it but because they are one with it” (80). So it remains undecided from Sacrifice whether the difference between myth and gospel is qualitative or quantitative. Such ambiguities are not uncommon in Girard’s writings, of course, and perhaps testify to the nuances of mimetic theory.

With regard to the texts of the great religious traditions—specifically, the Hindu and Buddhist traditions referred to in Sacrifice, however indirectly or fleetingly—it seems that Girard is working toward, or out of, a sense that they are situated somewhere “between myth and gospel.” Or to use the term which Girard applied to biblical passages, they are “mixed texts,” a mixture of “romantic” and “novelistic” elements.

Why is this important, and why does it make Sacrifice a significant “Breakthrough in Mimetic Theory”? The answer is that in this text Girard asserts, in principle, the compatibility of his thought with non-Christian faith traditions. This theme was complicated in Girard’s later years by his conflicted comments on Islam (and whether it represented, at least in some of its aspects, a return to the archaic sacred). More generally, it is all too easy to discern a kind of Christian supersessionism in much of his writing, not least from some of the “evangelical” passages in this final chapter three.

Nevertheless, Girard explicitly draws back from such a conclusion (87-88) by identifying the anti-sacrificial and even non-sacrificial inspiration in the most advanced parts of the Vedic tradition, as discussed above. Such passages suggest a trajectory away from sacrifice, analagous to the one Girard traces in the Judeo-Christian scriptures.

Sacrifice is not in any sense a serious engagement with the Vedantic traditions. Paradoxically, Girard shows his respect for the “perspicacity” within such traditions precisely by not even pretending that he is doing proper research. His access to the stories he discusses is a largely unadmired text, written by a French author in 1898. It is the same insouciance which has outraged biblical exegetes and Shakespeare experts, when Girard intruded onto their territory while showing very little interest in their expertise.

Since the publication of Sacrifice, scholarship on mimetic theory and non-Christian faith traditions has blossomed, in collections such as the Palgrave Handbook of Mimetic Theory and Religion (eds. Alison and Palaver, 2017), Mimetic Theory and World Religions (eds. Palaver and Schenk, 2017), and Mimetic Theory and Islam (eds. Kirwan and Achtar, 2019). A “hermeneutic of generosity” would allow that Sacrifice opened a door—an awkward rusty door, but serviceable—into this area of research “between gospel and myth,” which scholars other than Girard have been able to explore more fully.

Unearthing Violence and the Sacred in Turkey

Andrew McKenna

Loyola University Chicago

Ian Hodder, ed. Violence and the Sacred in the Ancient Near East: Girardian Conversations at Çatalhöyük. London and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019. Pages xiv + 259.

This volume is the product of the fortuitous encounter of two expats, English and French, at a big American university in the early years of our century. Its editor, Ian Hodder, has been presiding over archeological excavations at the dwellings of Çatalhöyük in Turkey (circa 7000 BCE), one of the biggest Neolithic sites and deemed the most symbolically elaborate. René Girard was invited to attend deliberations about the violent imagery on its walls at Stanford University in 2006. As the preface states, “Girard rather took the group aback by presenting a fully worked through and thorough analysis of the symbolism of the site.” A version of Girard’s paper was published in How We Became Human: Mimetic Theory and the Science of Evolutionary Origins edited by Pierpaolo Antonello and Paul Gifford (Michigan State University Press, 2015; reviewed in Bulletin 61). This earlier book contains other essays about this site and about another, not too distant one, Göbekli Tepe, dating from three thousand years earlier.

Rather than dismiss the interpretation of a self-described armchair anthropologist, Hodder chose to encourage closer attention to insights afforded by mimetic theory. This resulted in two onsite visits by eminent mimeticians (Johnsen, Anspach, Dupuy, Chantre, Palaver, Alison) in the company of no fewer than nine hard knuckle paleo-archeologists who joined the expedition, and whose fine grained analyses in this volume provide evidence of violence. The book is a remarkable exercise in collaboration throughout, as each contributor cross-references the views of the others; rather than a vertical stack of interpretations, it reads polyphonically as a lively testimonial to genuinely interdisciplinary research.

Mimetic Theory and Islam

Wolfgang Palaver

University of Innsbruck

Michael Kirwan and Ahmad Achtar, eds. Mimetic Theory and Islam: “The Wound Where Light Enters.” New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019. Pages x, 178.

My review is not really the perspective of an interested outsider who was not involved in the genesis of this book at all. Together with Sheelah Treflé Hidden and Michael Kirwan, I organized two conferences on mimetic theory and Islam that took place in London (2013) and Innsbruck (2016). This book is the partial result of these two conferences and I am grateful to both Michael Kirwan and Ahmad Achtar for editing this book and providing it with an extensive and very helpful introduction. My own contribution to these two conferences focused on the Abrahamic Revolution, on which two different articles were published elsewhere (The Palgrave Handbook of Mimetic Theory and Religion, Palgrave, 2017, and Mimetic Theory and World Religions, Michigan State University Press, 2018). The two editors summarize this concept very well in their introduction. There were also other contributions to these conferences that either were published elsewhere or are forthcoming as part of a whole book. Michael Kirwan summarizes the contributions of John Tolan, Ian Netton, Adnane Mokrani, and James Alison in his concluding chapter of the present book.

This book is not the final world on mimetic theory and Islam but an opening of a very much-needed discussion between scholars coming from different religious and disciplinary backgrounds. The editors provide the readers with a brief overview of mimetic theory: they introduce the concept of the “Abrahamic Revolution” that comprises the shared exodus of the three monotheistic religions from archaic religion, give an outline of a theological anthropology helping mimetic theory to remain open for differences between these three religions, and summarize in a helpful way the different contributions to this book.

Besides the introduction, the book is divided into three parts. A first main part called “Texts” comprises those contributions that focus on main texts in the Qur’an or the Bible. Zekirija Sejdini, a Muslim scholar from the University of Innsbruck, focuses on key passages in the Qur’an to provide an Islamic anthropology. From the perspective of mimetic theory, his reflections on human envy and ways to counteract enviousness are most important. Ahmad Achtar, one of the editors and a Muslim scholar based in London, reflects on Adam and Eve in the Qur’an by applying mimetic theory. The next three articles deal with texts that are central for my understanding of the “Abrahamic Revolution”: Abraham, the Binding of Isaac, and the story of Joseph and his brothers. Michaela Neulinger-Quast, a Catholic theologian from the University of Innsbruck, deals directly with the Qur’anic Ibrahim and expresses her skepticism regarding the notion “Abrahamic religions.” She does not convince me to dismiss the concept of the “Abrahmic Revolution,” but she is right to address differences between the Islamic and biblical understanding of Abraham that should not be dismissed too quickly. Sandor Goodhart, a well-known expert in mimetic theory and Judaism, reflects on Jewish and Islamic versions of the Abraham story to demonstrate that both traditions “share a fundamental orientation regarding anti-idolatry” (82). Michel Cuypers, a Catholic specialist on the Qur’an based at the Dominican Institute for Oriental Studies in Cairo, provides a rhetorical analysis of Surah 12, dedicated to the Joseph story. His careful reading of this text is an important starting point for future comparisons between the biblical Joseph story and the Qur’anic version of it. In my eyes, this story is an important bridge for scholars in mimetic theory to engage with Islam because it was so often used by Girard to address the biblical difference vis-à-vis archaic myths.

The next part of this book is called “Traditions” and comprises engagements with different Islamic traditions. Habibollah Babaei from the Department of Civilization Studies at the Academy of Islamic Science and Culture at Qom in Iran reflects on spiritual love and sacred suffering in his comparison of the Shi’ah perspective with mimetic theory. Oemer Sener, a research fellow at the Dialogue Society in London, engages with two contemporary Muslim thinkers as models of non-rivalrous interaction: Fethullah Gülen and Seyyed Nasr.

The final part of this book (“Christianity and Islam in Resentful Modernity”) comprises four contributions. Thomas Scheffler, a German political scientist with special expertise in Islam, carefully analyzes Girard’s view on Islam and Islamism, not overlooking some of his blind spots. This part of his article should become required reading for mimetic theory scholars interested in Islam. He also recommends the future use of mimetic theory for a better understanding of the history of Islam. Yanniss Warrach, a faculty member of the religious sciences department at the École Pratique des Hautes Études-La Sorbonne in Paris, reflects on his experiences as a Muslim prison chaplain in France. With his description of five types of prison violence, he addresses a topic that is also close to mimetic theory. Wilhelm Guggenberger, a Catholic theologian at the University of Innsbruck, engages with the Muslim brotherhood in Egypt by reflecting on its relation to religion and to the mimetic category of resentment. Michael Kirwan, a Jesuit and theologian at The Loyola Institute at Trinity College in Dublin, concludes the book by summarizing contributions absent in this volume and by emphasizing that mimetic theory should not remain a “theory about religion” only, but has to become more and more a “spiritual and theological exploration” (170).

As I said before, this book is not the final answer on mimetic theory and Islam but a very important starting point for future engagements that can build on this volume. Some errors and misunderstandings of mimetic theory occur in some of the contributions that have to be mentioned here, too. At one point Goodhart attributes Girard’s apocalyptic vision to his reading of the Book of Revelation (66). Girard, however, never touched this book of the New Testament but always talked about the apocalyptic texts in the Gospels. Babaei claims that Girard maintains a “violent human nature” (108), which is also not correct. This is definitely going beyond Girard’s emphasis that the normality of human conflicts should not be overlooked because he repeatedly distanced himself from concepts maintaining an aggression drive or a violent human nature. Such misunderstandings will more likely disappear if mimetic theory goes more strongly towards a spiritual and theological exploration as Kirwan recommends in his concluding chapter. To turn in this direction might also lead to a more consistent distinction between the sacred and the holy as it was expressed in Girard’s last book Battling to the End and as Kirwan refers to a paper by James Alison (170). The editors distinguish in their introduction only between the false and true sacred (9). To emphasize the holy, instead, would be a stronger turn towards saintliness that is so much needed in our challenged world of today.

Our Royals

Wiel Eggen

Dutch Girard Society

Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster: Dualism, Centralism and the Scapegoat King in Southeastern Sudan. Revised, illustrated edition. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2017 (Orig. Kampala, Uganda: Fountain Publishers, 1992), pages xx + 535 (with the support of Imitatio Foundation).

This keenly-awaited update of Simonse’s 1992 thesis on the Rainmaker-Kings’ dramatic role in Nilotic Sudan takes me back to the grim comments that Girard’s 1972 La Violence et le Sacré received at the Parisian Laboratoire d’Anthropologie. How could a literary critic reduce the vast complexity of myths and rituals to the sole psychic factor of mimesis as cause of rivalry and scapegoating? How could he base all cultural institutions, including the regicides of sacred kings, on sacrificial rites, which Lévi-Strauss had termed “absurd acts” amidst man’s classificatory exploits? Headed by Luc de Heusch, a group of specialists working mainly on African data had just set out to apply the structuralist method to the kingship enigma and dubbed Girard’s hypothesis of the scapegoat king a poor avatar of Christian ideas on the divine son sacrificing himself for his people. So an anthropological test of that hypothesis was urgently called for.

Encouraged by his university and directed by Matthieu Schoffeleers, a co-founder of the Dutch Girard association, Simonse availed himself of a teaching job at Juba University to tackle this momentous task in the mountainous Sudanese Equatoria province, southeast of Juba, where regicides of Rainmaker-Kings had been reported among a variety of peoples belonging to four language groups. During half a decade of hazardous fieldwork and extensive archival research, Simonse examined two dozen cases of well-documented regicides from the mid-1800s to date. With ethnographic rigor he related them to the material conditions of that terrain, plagued by erratic rainfall, and to their social setting, marked by constant conflicts, internally as well as with the colonial forces, who had vowed to “pacify” these tribes that Dr. Lafargue in 1845 had dubbed “the most beautiful human race” (94). Though his inquiries were often hampered by ongoing hostilities of people ever keen on displaying their prowess—even through mock charges at greetings—and despite missionary and administrative archives being so far afield, the result was a limpid, well-written, and groundbreaking thesis.

This often quoted but scarcely accessible thesis has now been given an enhanced edition. Its imposing mix of empirical rigor and theoretical daring has been enriched with two extended indexes, with dozens of text-related photographs of the life in interspersed villages encircling those mounts, and with a lucid rewording of the opening chapter and the conclusions, backing Girard’s vision of the sacred kingship in a solid, slightly modified reading. Mark Anspach’s foreword praises the judicious choice of relating the centralized royal model to the underlying “segmentary” and dualist set-up of the dispersed polities, of mostly under 100,000 inhabitants. Citing Hocart’s thesis that not the size of the terrain, the population, or the wealth, but rather the social structure determines the institution of kingship, Simonse analyzes the role of the central figure of the Rainmaker-King in societies that are basically dualistic and egalitarian, with numerous synchronic and diachronic oppositions. We find villages with rivaling subsections, divided in exogamous moieties, and ruled by generational groups (monyomiji), ever about to defend their authority against the ousted predecessors and, especially, against their younger challengers, eager to succeed and reduce them to “children.” This competitive setting is further complicated by tensions between clans and families, and by the opposing ties each person has with paternal and maternal kin. As from the mid-19th century, moreover, colonial powers had added more causes of conflict by appointing chiefs, providing lethal weapons, and opening up trade routes.

In this febrile setting of frequent brawls between societal segments, the people’s chief concern is with issues depending on forces beyond their control, believed to be the area of witchcraft and symbolic powers. Most clans have some officials to deal with such issues. Yet the capricious spheres of agricultural or conjugal fertility, hunting success, and notably the erratic rainfall surpass these clan officials. They depend on “Master” specialists, or Fingers-of-God (ch. 13), with the Rainmaker-King being central among them. They are installed and surveyed by the ruling monyomiji and hold ambivalent powers of blessings and curses, which lead to numerous feuds between them and the people. The Kings, in particular, are to procure pacifying blessings, subsumed in the symbol of rain-making, but they often unify the people more by their irritating demands and threats of provoking disasters. Consequently, rather than portraying the Kings in evolutionist terms as precursors of elaborate kingdoms elsewhere, or as degraded imitations thereof, Simonse offers a “thick reading” of the social dramas, in which they struggle to hold their own by the leverage of that crucial rain power, symbol of their wider calling to procure blessings and thwart harm. He extricates the mesh of opposing forces surrounding these Kings and their hazardous position as scapegoats of adversities, which may sometimes deteriorate into a regicide, even with an own son as gang-leader. His study of the build-up and unfolding of such dramas belies the notion of kings willingly sacrificing their life for the people. They rather defend themselves by various strategies, often antagonizing the people deliberately by the abuse of their position. Thus, “reciprocal victimization” (450) marks the rhetoric and practice of both the people’s dualist feuds and their stand-off with the centralizing royal figure.

In cases of actual regicides, Kings are usually charged with failing to avert major disasters from their people, the “husband” (221) whom they were to serve as a wife, but actually hated and killed. By their role at seasonal rites and sacrifices, they ought to “digest” and sooth social rivalries, while being mediators, judges, and a refuge. But they are accused rather of provoking disasters. While such conflicts are commonly appeased, they do at times end tragically. Any drought may urge the monyomiji to consult a diviner, formulate accusations against the King, impose fines, or worse, if he does not repent and bring rainfall.

Applying Girard’s hermeneutic tools, the book thus portrays the Kings as scapegoats, who are mostly mistrusted by their “husband,” the polity. It, thereby, interrogates the birth of centralized state power, showing it to be a convoluted process. This reminds me of Pierre Clastres, who, in 1972, welcomed Girard’s controversial book as backing of his own argument that rituals are a society’s tools to prevent, rather than to foster centralization, and the ecologist reading of rituals as the people’s means to urge respect for nature’s demands. The Sudanese data also tally with my own findings among the acephalous Banda people, further to the West, who see the government-imposed chiefs as the principal witches and as honorable “dirt.” Some elderly Banda may even deliberately pose as witches to inspire awe and respect, threatening to cause harm when they are irritated.

Since the Banda call the holders of an office or property its “Mother,” rather than its “Master,” feminist researchers might sift through this book’s rich material and use its detailed indexes to scrutinize the mainly male theater of prowess against the backdrop of the feminine roles. What does it mean that, along with blacksmiths, only women can circulate unarmed (224), and are they mediators, comparable to the King’s specific role? Why should a maternal uncle be entitled to damages, when his nephew is made a King and put “in the center of evil” (44), even if the latter openly campaigned for the job, to the point of courting the queen-widow of the predecessor? What is the role of these queens that are no less controversial and act as the rain-power’s true depositories (301 ff), and why are female relatives to guard a deceased King’s tomb (410)? Might here even be an answer to Eric Gans’s critique of Girard for ignoring the role of language and the semantic deferral in solving the mimetic crisis? For the women are not only the transmitters of linguistic skills, but prove to be the instance urging a deferral when violence rages.

But Simonse is surely well-justified to leave these aspects aside and devote his closing Part IV entirely to the King’s ambivalence as society’s root of blessings and scapegoat of disasters. He slightly modifies Girard’s vision of their dying symbolically at their ritual installation. He rather speaks of “victims in suspense,” since they are active agents involved in plots of “reciprocal victimization” with the people and their monyomiji. The edgy events at New Year ceremonies or at a king’s natural death illustrate an interface between the ritual and social power that seldom receives the anthropological attention it deserves.

While the book, then, clearly advances anthropological theory and mimetic studies, for both Simonse and his co-researcher Eisei Kurimoto it was of equal import that its findings allowed them to contribute to local peace initiatives, such as the 2009 Pax Christi International-sponsored Torit conference—proceedings published in 2011 and online—which was devoted to the monyomiji age-group’s role in the democratic, modern state, with kingship’s centralizing role as a backdrop. The reading of actual regicides as a sorry outcome of social dramas, rather than as premeditated political assassinations or as rituals, has us witness a complex maneuvering that seeks to keep the scapegoat alive as a unifying factor as long as possible, thus creating, in Anspach’s words, the interval for progressively transforming “victims into kings”—or say, into our royals and their derivatives.