In this issue: updates about two new COV&R initiatives and our summer meeting, plus reviews of books by Giuseppe Fornari and Beatrice de Graaf.

Contents

Letter from the President: Exciting Developments in COV&R, Martha Reineke

Editor’s Column: Mimetic Theory in Vogue, Curtis Gruenler

Homo Mimeticus Final Conference

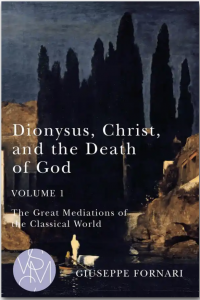

Giuseppe Fornari, Dionysus, Christ, and the Death of God, reviewed by Anthony Bartlett

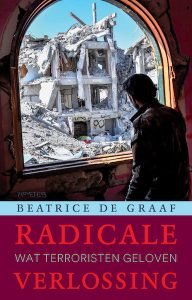

Beatrice de Graaf, Radicale verlossing: Wat terroristen geloven, reviewed by Erik Buys

Letter from the President

Exciting Developments in COV&R

Martha Reineke

Northern Iowa University

I am delighted to update you on two initiatives begun last fall in our COV&R community.

Interview with Luke Burgis

At our summer meeting, a session featured a conversation between Matt Packer and Luke Burgis about Luke’s new book Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life. Someone suggested in the Zoom chat that the conversation had all the marks of an interview made for prime time. I apologize for not taking note of the person who posted this marvelous suggestion. With the support of the Social Communications Committee, I invited Matt and Luke to record a new conversation. I was thrilled when they accepted the invitation and am even happier with the results. Matt and Luke have wonderful rapport, and they engage each other in a stimulating and insightful, hour-long conversation. I hired Isaac Hackman, a videographer and recent graduate of UNI with whom I had worked on course videos, to create a raft of social media products for sharing among our members and, particularly, with non-members. Social Communications Committee Chair, Steve McKenna, was the point person on the development of these products. Thanks to Steve’s suggestions, we have a robust experiment with these products underway.

Feedback Please: Two years ago, the membership authorized the Social Communications Committee to use resources from our member dues to enhance our digital outreach. The Burgis/Packer interview is an experiment in support of that goal. The Committee and Board hope to learn from the interview what kinds of digital products are most useful to members and to others for disseminating knowledge of mimetic theory. Based on the results, we will be able to encourage our members to develop more products. What will be the biggest draw: An hour-long interview? A 15-minute conversation? A podcast? A teaser that sends the viewer to our website to view the suite of products? We have no idea! That’s why we need your help with this experiment in digital outreach.

Please click through to these products and share them on social media. They are posted on COV&R’s website as a playlist that includes the conversation both as a whole and broken into four parts. The teasers (45 seconds to 1 minute in length) are ideal for sharing on social media. We hope that every member who uses social media will share one or more of these:

- The Scapegoat Solution

- So Obvious It Can’t Be True

- Name Your Models

- Love in Mimesis

- Celebristan and Freshmanistan

If you prefer to access the Burgis interview as a podcast, please subscribe to “A COV&R Convo” via your favorite podcast provider. A transcript of their conversation is available on the Member Page.

At its January Board meeting, the COV&R Board decided to support a podcasting project proposed by Julia Robinson-Moore. The Board also created an ad-hoc committee that will draft a set of criteria that can be used to evaluate funding proposals from our members. With these proposed criteria and the results of these two experiments in digital outreach, the Board hopes to take an evidence-based approach to supporting future projects that will help COV&R expand the reach of mimetic theory. The goal is to have a process through which members can submit proposals to the Social Communications Committee to request funding for the production of digital media. Demonstrated interest in such products, confirmed by viewing statistics on extant products, and future funding proposals to the Committee will be instrumental to moving forward with that initiative.

Has watching or listening to the Burgis/Packer interview resulted in a brainstorm? Please do reach out to me or to Steve McKenna, Chair of the Social Communications Committee, with recommendations for future A COV&R Convo videos and podcasts.

Has watching or listening to the Burgis/Packer interview resulted in a brainstorm? Please do reach out to me or to Steve McKenna, Chair of the Social Communications Committee, with recommendations for future A COV&R Convo videos and podcasts.

Listening Sessions

The COV&R Board drafted a statement on Diversity and Inclusion at its July, 2021, meeting. During the fall, COV&R members participated in four listening sessions, held at times convenient across time zones where members live (Americas, Europe, and the Pacific), to respond to this draft and to discuss how COV&R may become a more inclusive community. At its January meeting, the Board discussed the listening sessions which we attended and reviewed notes from each session. These notes are available for reading at this link accessible to members only.

The Board notes that support for this initiative is widespread among the membership. During the listening sessions, members offered specific suggestions for becoming a more inclusive organization. The notes from the sessions will enable the Board to imagine new ways to support programming at our annual meeting and to build community throughout the year. Members also shared ideas for improving the language in our draft proposal. We look forward to sharing a revised draft with you at the business meeting in Bogota that will reflect an emerging consensus among our members.

Standing out for me from our conversations during the listening sessions are these key elements:

- Hospitable: A striking feature of the listening sessions was that COV&R members want all members—new and continuing—to feel genuinely welcome in COV&R. As we began enumerating specific manifestations of diversity we want to embrace in COV&R, every “what about” addition seemed to move us closer a vision of inclusivity that may best be described as “radical hospitality.” This vision is reminiscent of Girard’s evocation of the open doors of the Christian “hospital:” the l’Hotel-Dieu (I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, p. 167).

- Intentional: Standing out also in the listening sessions was a commitment to action—a practical engagement by our members in ways that empirically demonstrate “You are welcome here.” Members want to engage in education, research, active listening, and strategic planning to put intellectual and emotional muscle into our welcome. Our hard work of rethinking and reframing prior engagements with mimetic theory will support hearing from new voices and accessing new perspectives for mutual learning.

- Commitment to listen: Expressed also in the listening sessions was a desire to attend carefully to persons who have expressed concern about their underrepresentation in COV&R. Members want to learn from those expressing unease, and we desire to support conversations and transformations based on these encounters. Even when confronted with difficult, uncomfortable, and personally challenging dialogues, that commitment stands out.

- Decenter our voices: Emerging from the listening sessions is an acknowledgment that, in order to embrace diversity non-rivalrously, we will need to decenter our own stories. Those of us who are accustomed to holding the floor, sitting at the head of the table, etc., may experience loss and feel threatened initially. We may find navigating choppy waters frightening and wonder if it is possible to stay the course. But the listening sessions also suggest that our membership sees value in a decentering process that promises to add depth and perspective to our work in mimetic theory and its application. With this in mind, we are committed to doing the work of becoming a more inclusive organization, notwithstanding painful moments.

- Focus on process: Visible, above all, in the listening sessions was the sense that we are engaged in an ongoing activity. We are not checking off a diversity box, as it were, or aiming to get a policy or narrowly conceived outcome “right.” Rather, we are writing a new chapter in an ongoing story of our organization. As we move forward, it will be important that this commitment to process, characterized by hospitality, intentionality, and care-filled listening is attested to in a statement on diversity and inclusion to be offered for consideration by our members in July.

Editor’s Column

Mimetic Theory in Vogue

Curtis Gruenler

Hope College

As a fan of New York Times columnist David Brooks, I was excited to see him mention René Girard in his February 10 piece, especially in connection with The Beatles. Recent findings about how music becomes popular, he suggests, support Girard’s work. For those interested in more, he links to a long article, “How to Know What You Really Want,” in which Luke Burgis nicely digests some of the practical recommendations from his book Wanting. Like Burgis, Brooks pivots from the “negative story” of mimetic desire to its potential for illuminating our responsibility in creating culture, starting with what desires we model for others. Brooks has long offered insights based on a relational view of human being, as in his 2011 book The Social Animal, and mimetic theory fits right in.

Another sign of the “vogue” that Brooks says Girard is currently enjoying: “Imitation Game,” the cover story of January 29, 2022, issue of the New Zealand Listener, the nation’s bestselling magazine of current affairs, occasioned by Burgis’s book and written by the Bulletin’s book review editor, Matthew Packer. It’s one of the most accessible introductions to Girard I’ve seen. Our thanks to the Listener for giving permission to post it on our member articles page. It was also picked up by the New Zealand Herald.

Also, for what it’s worth, Girard’s Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World currently sits at number 1 on Amazon’s list of bestsellers in the category of literary theory. It has hovered in the top 5 for the past few years while various other titles come and go.

Also, for what it’s worth, Girard’s Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World currently sits at number 1 on Amazon’s list of bestsellers in the category of literary theory. It has hovered in the top 5 for the past few years while various other titles come and go.

COV&R members should by now have received Violence, the Sacred, and Things Hidden: A Discussion with René Girard at Esprit (1973), translated by Andrew J. McKenna, with a foreword by Andrea Wilmes, the newest volume in the series Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory from Michigan State University Press. Also in the same series, The Time Has Grown Short: René Girard, or the Last Law by Benoît Chantre, translated by Trevor Cribben Merrill, is due out in May, 2022. In MSUP’s series Studies in Violence, Mimesis & Culture, Toward an Islamic Theology of Nonviolence: In Dialogue with René Girard by Adnane Mokrani has been announced for July 2022 and How to Think about Catastrophe: Toward a Theory of Enlightened Doomsaying by Jean-Pierre Dupuy for November 2022. As described in Martha Reineke’s recent letter to members, new books in these two series will no longer be distributed at no cost to COV&R members because Imitatio has discontinued its funding for that program. Instead, members will receive a 20% discount on all titles in both series. The discount code for the back catalog is available on a members-only page of the COV&R website. When new books are available, COV&R will coordinate with the press to announce a discount code.

As mentioned in the previous issue, COV&R members who are familiar with mimetic theory’s connections to Dramatic Theology are encouraged to take a look at the call for papers for a special issue of Religions on Dramatic Theology. Contributions are welcome. The deadline for submissions is 5 September 2022.

Forthcoming Events

COV&R Annual Meeting

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia

June 28-July 2, 2022

Emerging Crisis:

New Humanities and the Mimetic Theory

Call for papers

The Critical Thinking and Subjectivity Research Group of the Philosophy School of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana invites proposals until April 30, 2022. The approximate length of papers to be delivered will be 9000 words (approx. 30 min.). Proposals should include contact information, a title and a 300-word abstract. All submissions should include a statement at the end of the proposal listing technology needs. Proposals must be submitted in English.

Proposals should be emailed to Mr. Ronald Rico.

COV&R members are encouraged to distribute the call for proposals to their students and friends.

Possible fields for paper proposals:

We have focused our call for papers on the CRISIS. The crisis refers, on the one hand, to the new social movements, and to the excessive response of the public forces across almost all the planet. On the other hand, the pandemic caused by Covid-19, with an enormous death toll and serious economic effects, exposes the unjust distribution of wealth and opportunities in the world.

But new perspectives in the humanities have emerged in a context where the academy is under pressure to prioritize knowledge of the future and entrepreneurship, against the knowledge of the past and of what is not useful. This is an old crisis. But the situation of the last 50 years has produced movements in the humanities that only emerge in conflict against another form of the same humanities, fragmenting knowledge into rival ways of approaching the academic enterprise.

Our focus is on mimetic theory, its discussions in the different perspectives with which it is approached and what is assumed in the face of the different problems that are worked on. All papers that want to show their developments of and new discussions on mimetic theory are welcome.

In addition, working from mimetic theory and in dialogue with the new humanities, we would like to invite your proposals on:

- Ways to understand the new social movements

- Experiences of social mobilization that can be reflected from mimetic theory

- Alternatives to reduce the violence of state security forces

- Approaches to understand the crisis caused by the covid-19 pandemic at local, national, regional and global levels

- Responses to the effects that the pandemic has produced accompanied by the reflection unleashed by mimetic theory

- Regional perspectives to approach mimetic theory, such as readings from the Global South, the heritage and developments of liberation philosophy and theology, and everything derived from the decolonial turn that affects issues related to ethnicity, power, gender, knowledge, and pedagogies

This is the reason why we invite people from different fields of knowledge to participate in this meeting, always with the reference of the mimetic theory proposed by René Girard and with the aim of having serious conversations in search of better understandings and solutions to the current crisis.

Seminars/workshops:

The organizing committee also welcomes proposal for practitioner-focused, interactive workshops that relate to the work of Girard or the conference theme. Such sessions could take different forms (e.g., workshop-style, forum, discussion group, panel) and may cover areas of interest for a significant group. Please provide a description and rationale for an inter-active workshop on a particular topic to be facilitated for approximately 45 or 90 minutes by appropriately qualified persons. Working groups can be proposed in Spanish.

Schwager Prize:

To honor the memory of Raymund Schwager S.J, the Colloquium on Violence and Religion is offering an award of $1,500 shared by up to three persons for the three best papers given by graduate students at the COV&R 2022 meeting. Receiving the award also entails the refund of the conference registration fee. The winners also receive a certificate.

Students presenting papers at the conference are invited to apply for the Raymund Schwager Memorial Award by sending a letter to that effect and the full text of their paper in an e-mail attachment to Roberto Solarte, organizer of the COV&R 2022 meeting and chair of the three-person COV&R Awards Committee. The paper should be in English, maximum length: 10 pages double-spaced. Because of blind review, the author name should not be stated in the essay or in the title of the PDF file. Due date for submission is the closing date of the conference registration, May 27, 2022. Winners will be announced in the conference program. Prize-winning essays should reflect an engagement with mimetic theory; they will be presented in a plenary session and be considered for publication in Contagion.

Host and site:

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana is a Jesuit university which is distinguished as one of the best in Colombia and Latin America. Lodging options are at nearby hotels.

For more information about the conference and lodging options, see the conference website.

Bogotá is a city with many places of interest such as the gold museum and the colonial zone. Colombia, the place of the magic realism— as the Nobel prize winner, Gabriel Garcia Márquez would say—is a country with beautiful places like Cartagena, the coffee zone, magical little towns, and Leticia in the middle of the Amazonian jungle. It is one of the world’s best repositories of surviving fauna and flora which can be visited in a several ways. One of the outstanding activities available is bird watching, as Colombia is considered a world leader in this field.

Travel Grants:

COV&R offers travel grants under the following conditions:

- Possible recipients are grad students or practitioners of mimetic theory (e.g., NGO/non-profit staff; journalists, government employees). Preference is given to graduate students but practitioners of mimetic theory are also encouraged to apply.

- Possible recipients have an accepted proposal and offer a presentation at the conference.

- Grants are awarded at the conference.

- Attendees are eligible one time only for a travel grant. Priority will be given to applicants who have not received a grant previously.

- Grants are given on a first come, first served basis.

- The registration fee will be waived for travel grant recipients.

To apply for a travel grant, write to the Executive Secretary of the Colloquium and explain your need and eligibility for the grant. He will be in touch with the conference organizers, so that grants will be awarded according to the Colloquium’s specifications

The Mimetic Turn:

Final International Conference on Homo Mimeticus

KU Leuven, Belgium

April 20-22, 2022

The ERC-funded project Homo Mimeticus: Theory and Criticism (HOM) hosted by the Institute of Philosophy and the Faculty of Arts at KU Leuven, Belgium, is pleased to announce its final international conference on April 20-22, 2022 (online; in-person option tbd). Furthering a re-turn of attention to mimesis HOM has been promoting over the past 5 years, this transdisciplinary conference is titled, The Mimetic Turn. Its general goal is to continue mapping the protean manifestations of mimesis (imitation, but also identification, contagion, performativity, simulation, mirror neurons, et al.) from a Janus-faced perspective that looks back to this concept’s genealogy to better look ahead to the challenges of the present and future. HOM’s overarching hypothesis is that from the linguistic turn to the ethical turn, the affective turn to the new materialist turn, the neuro turn to the posthuman turn to the environmental turn, there is a growing re-turn of attention to the ancient yet always new realization that humans are an all-too-mimetic species—or homo mimeticus.

Keynote speakers will include Rosi Braidotti, Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen, and Vittorio Gallese.

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the book review editor, Matthew Packer.

Dionysus, Christ, and the Death of God

Anthony Bartlett

The Bethany Center for Nonviolent Theology and Spirituality

Giuseppe Fornari, Dionysus, Christ, and the Death of God, Volume 1: The Great Mediations of the Classical World, Volume 2: Christianity and Modernity.

Studies in Violence, Mimesis & Culture, East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2021, Pages: iv + 633, xiv + 574

Giuseppe Fornari’s epic two-volumed work, Dionysus, Christ, and the Death of God, provides a sweeping intellectual synthesis hinged around core Girardian ideas. Correspondingly, Fornari’s guiding concept of “mediation” seems to have more than a little Hegelian feel to it. But Fornari is eminently a Nietzchean thinker, rather than Hegelian, focused throughout on cultural genealogy. And the twin burning lights of Dionysus and Christ, as in the title, create a deep undercurrent of duality rather than a grand unity. Thus, this splendid work of scholarship may be said to have two somewhat separate, if not contrary, intellectual axes or planes: a systematic thought of “mediation” providing philosophical order and intelligibility and, at the same time, the immensely destabilizing, unresolved tension between Greek and Gospel heroes, a tension which, by Fornari’s own forensic account, drove Nietzsche mad.

At the heart of this crackling cocktail is the question of modernity, its meaning and destiny, and Fornari is to be profoundly congratulated on raising the issue in such a substantive, possibly definitive, way. For Fornari, modernity is to be understood as the loss of mediation as such, provoking the volcanic eruptions of the last century, each understood as a desperate search for ideological compensation. But the loss of mediation is itself its own form of mediation, especially if we consider it at least partly a crisis left us by Christ, i.e. both a chaos and the possibility of new meaning. On the one hand, modernity is the attempt to deny and transcend this situation in totalitarian movements, leading to the murderous horrors of our time, figured for the author in the literary-personal paradigm of Nietzsche. At the same time, elements of culture are left in a peculiar in-between situation, of sacrificial mediation and a compassionate identification with the victim brought by Christ.

Fornari lays out his work in two compositional halves corresponding to the two volumes. The first half offers an imposing panorama, first of all setting out his “gnosiological” framework, and then examining in detail the material of his subtitle, “The Great Mediations of the Classical World.” His intellectual mentors include Freud, Durkheim, Bataille, Nietzsche of course, and, pivotally, Girard. Throughout his work he returns to the author of Violence and the Sacred and Things Hidden to invoke the latter’s ground-breaking generative anthropology, and yet to declare a decisively different angle of approach. Most significantly, Fornari accuses Girard of “noumenal negativism” (I, 64), meaning that he believes Girard, in his descriptions of the origin of culture, brings about a cataclysmic disappearance of the actual world of instinctual objects, to be somehow, inexplicably, restored in the symbolic order via the newly transcendent corpse of the victim. Thus, biological reality is vaporized to be brought back only in the black light of the death of the victim and the dread it inspires. In contrast, Fornari offers a progressive series of proto-human crises in which the instinctual object never disappears, but then, ultimately, becomes mediated via an ecstatic perception which is the corollary of victimary killing.

Fornari’s thought is a kind of generative phenomenology, a combination, we might say, of Husserl and Girard, something he hints at but does not develop. “The ecstatic-objectual mediation is not a dreamlike projection, but… a new level of reality, definable neither as imaginary nor simply objective… existing in an unprecedented relationship between a detached external object and a collective subject that to some extent corresponds to Husserl’s correlation but in a radically historical and genetic fashion. This mediatory and mediating process is a new symbolic reality, open to possibly endless future symbolic developments… representing the true lifeblood of every culture and every human being” (I, 83). In sum, Fornari’s thought is a theory of human mind, a phenomenon which, despite its crucial relation to the victim, always retains its functional independence.

At one level the question might seem recondite, representing something which may in fact be contained obliquely in Girard’s descriptions though passed over hurriedly. But Fornari is certainly right to highlight the problem, and then, more substantively, his solution of a collective mediatory praxis proves an open and fruitful pathway to move the discussion forward. On its basis he is able to document and analyze the actual history of diverse cultures, especially those surrounding the Mediterranean, which in some measure become conscious of the aboriginal conditions of humanization. Enter Dionysus, the horrifying rites of omophagia (“the absolute starting-point for symbolism,” I, 81), and their cultural elucidations.

Fornari proceeds with accounts of Orphism, the Eleusinian mysteries, a number of individual majestic achievements of Greek Tragedy, and yet the ultimate aporia of Tragedy’s vision. This part of Fornari’s work enters a range and depth of historical and literary material that many, including myself, might feel not competent to argue with, and it certainly invites here its own evaluation from scholars in the field. However, broad results are clearly apparent, and certain remarks can be made. Firstly, as already suggested, Fornari makes Orphism and its Dionysian rites the ground-zero of anthropological understanding of sacrifice, and from the very beginning of his analyses he connects this to the figure of Christ. But the structural continuity is more than once blown apart, as a symmetrical mountain carved suddenly in two, by a critical element obliquely mentioned. For example, “Our indifference and mental sluggishness easily blind us to the difference between the brutal violence of archaic sacrifice and the real meaning of Christ’s Passion…” (I, 142). Or, later, in discussion of the Bible itself: “My basic thesis is that the Bible texts have no monopoly on the truth they contain; instead, the objectual truth of mankind regarding man, a truth variously attained by all human cultures, gradually makes its way, acquiring its own particular accent in the Judaic and Christian tradition…. Jesus did not come to bring knowledge of the victim and sacrifice in these representational and abstract terms, something inconceivable to his Jewish mind, or to any other mind in antiquity. He came to announce a joyful loving mediation with Yahweh whose inner dynamic is mutual forgiveness…” (II, 240). Expressions like this arise on the surface of text like wonderful sea beasts suddenly breaching, but Fornari but does not make them operative or systemic. In other words, the revelatory nonviolence of the Christ is an obvious question in his comparative approach, but it’s one Fornari does not thematize because it could possibly destabilize his universal mediatory concept.

Meanwhile, in his account, the rites of Dionysus serve as the starburst of ancient Greece’s greatest actual insight: murder is humanity’s generative misdeed, and the rites both repeat the origins and mediate salvation by ecstatic identification with the slain and reborn god. Orphism threw light upon human origins in its ecstatic attempt to escape them. Secondly, in sympathy, the great tragedians of Greece aimed at a solution beyond violent reciprocity but could not reach it (I, 355). In contrast, in Christ’s crucifixion and Resurrection the tragic phenomena were in fact overcome “with the living, victorious affirmation of the ideals of the person who suffered that tragedy unto death and thereby struck a deadly blow at the root of the symmetrical retaliatory logic that prevented the figures of tragedy from breaking out of the circle imprisoning them” (I, 355). Thus, knowledge of the victim at the basis of culture is indeed present in a favored way in the Judeo-Christian tradition, yet such knowledge is frequently present in other traditions and cultures (I, 223), apparent and realized in different ways and to different degrees.

All of which serves as a converse of Girard’s position, because Girard, rather than understanding the richly mediatory role of human culture, reduces everything to the victim and its disclosure in Christ. According to Fornari, Girard’s approach is absolutist, simplifying, polemical. His “adversarial schematism” (II, 225) attributes all knowledge and perfection to the Jewish and Christian traditions, to the Logos that emerges in and through biblical revelation apart from the fatally compromised human word (I, 373). On its own this material could have been sufficient for Fornari’s critical riposte to Girard, but he is by no means done. His continuation into a second volume recommences the story fully according to his second register, the seismic tension between Christ and Dionysus, and therewith the crisis of modernity.

Fornari is as much a biblical scholar as one of classical antiquity, and his second volume is an impressive work of critical thought, in laying out its assumptions, its knowledge of contemporary scholarship, and its evaluative textual findings. Jesus is a real historical agent in a real Judaic landscape, a setting deeply inflected by Hellenic cultural influence hand in hand with Judaism’s own prophetic history. Fornari gives core historical value to Jesus’ action in the Temple in the final weeks of his life; it is a “valuable interpretive key” (II, 199) throwing light on the historical Jesus, his meaning and plausible self-understanding. But it is at this point Fornari derives an interpretive framework which seems as narrow and formalistic as it is sympathetic to his overall treatment. He sees Jesus’ action in the Temple as a determinative protest at the supposed murder of Zerubabbel, the (possibly) Davidic descendant returning with the first waves of Babyonian exiles as governor (Haggai 1:1). Along with the murder of his prophet Zechariah, occurring at the hands of the then high priest, Joshua, and within the Temple precincts, this event earns Jesus’ excoriating denunciation feasibly spoken on the occasion of the Temple action itself (Matt 23:35-36, see I, 122-4, and II, 130-1). Jesus is aware that his obstruction of Temple sacrifice will bring about his death, and he invests his inevitable personal suffering with a regenerative meaning derived itself from ancient Yahwistic cult. In this cult the sacred monarch is fated to repeat sacrificially the god’s destiny of death. In historical times, the monarch as representative was able to displace the sacrifice onto a firstborn male, evidenced in the cult of Moloch (Hebrew root mlk/king; see I, 449). Jesus instead undergoes the original deadly travail in order to bring in the kingdom via the participation of the disciple in his very self, as made evident in the Eucharist.

Fornari states, “The theory that the sacrificial principle of divine metamorphosis was the specific and general precedent not only for the Eucharist as conceived and experienced by the first Christian communities but also for the Last Supper as conceived and experienced by Christ is fully confirmed” (II, 202). Thus, the Dionysian link is made once again, and Fornari also provides a corroborating examination of the Marriage Feast at Cana in John’s Gospel, gripping in its own right, demonstrating a Dionysian subtext in the writing.

There is evidently a large area for discussion here, both in details and general biblical hermeneutic. The elephant-sized problem is the general elision of Israel’s salvific history in the Exodus, and, in parallel, the large-scale absence of biblical apocalyptic. Apart from glancing references, there is no serious examination of this perspective and what its revelatory content might mean in Jesus’ trajectory. This is surely passive opposition to Girard’s considerable emphasis (especially in terms of the figure of Satan), but the narrowness of the Zerubabbel focus (including, it should be said, its hypothetical nature, lacking specific biblical testimony) has the effect of seriously diminishing the radically transformative historical arc expressed by sections of the Jewish community, preserving the liberative Exodus vision. The prophecy known as Second Isaiah introduces a transcendence of compassion that breaks the mold of human violence, especially in the figure of the Suffering Servant, and this spirit is later given new energy by the community behind the book of Daniel, expressly distinct from the militancy of the Maccabees. The Suffering Servant and his acute nonviolence is swallowed up in the Zerubbabel reference, and the equivalently nonviolent “one like a son of man” in Daniel—an apocalyptic code which, as Fornari underlines, is taken up by Jesus—is subsumed as “Son of God” and in the role of Mediator (II, 89-91).

These comments do not diminish the value of a great deal of Fornari’s exegesis, as well as his magisterial accounts of the historical development of biblical criticism from Spinoza onward. What they do suggest is an anomaly in Fornari’s overall method. As mentioned, the second axis of his work appears powerfully in the second volume, and nowhere more than his sixth and seventh chapter on the cross/crosses of the ancient and modern world. Where apocalyptic got very short shrift in the biblical treatment it appears thunderously here in its reactive worldish form—the perilous loss of mediation and the threat of totalitarian substitutes (II, 418-21), and of course the terrifying literary and spiritual benchmark of Nietzschean breakdown. What Fornari does not recognize is that the generative apocalyptic mediation of the New Testament is that of transcendent nonviolence. He in fact does know this but he mixes it with its converse: “The strangely real symbol of the crucified Christ shows that this world compared to the Greek world is more complex and diverse, and also more unresolved and suspended, envisaging a mediation that transcends violence alongside the usual mediations that inflict violence in the most atrocious ways…” (II, 346). He says this in respect of a particular and particularly gruesome official execution under the aegis of eighteenth-century Catholic France, and so his comment reflects the traditional “Christian” mediation of that world, one very much on the edge of crisis and revolution. But he never resolves the contradiction in its own terms, and hence the true nature of New Testament apocalyptic mediation remains obscured. In this way Girard’s “schematism” is avoided, but the latter may in this respect be more accurate to the nature of the case.

The question is critical when it is a matter of Christ’s Resurrection, something Fornari sees as phenomenologically real, i.e. it was an actual event for the disciples carrying its own new meaning. He says this: “…the Resurrection… shows us a reality superior to the subject/object coupling since it stands at the fountainhead of their formation and existence.” He goes on, however: “The difference between the Resurrection event and the ecstatic-objectual event I see to be at the origin of humankind is not a difference of quality but entirely a matter of degree and the capacity to retroact and reveal” (II, 485).

In other words, Fornari accords the Resurrection the same phenomenological status as the founding event of human mind, but, bizarrely, stresses there is no qualitative difference. What he intends for sure is that there is no “supernatural” element overturning the intramundane intellectual phenomenon evidenced at the beginning. Nevertheless, Resurrection is able, presumably by some increased brilliance, to retroactively disclose the sacrificial mechanism. This seems methodologically commendable: it preserves the single mediatory process, maintaining the basic continuity of the ecstatic-objectual world, i.e. the one founding phenomenology of mind/object. But the statement factually misses the radical novelty, the differend of the Resurrection. It seems evident there is a profound qualitative difference in the ecstatic-objectual event, i.e. the transcendent nonviolence of the Risen Crucified and the Father so revealed. Is it not this differential structure, in its intense proximity to Dionysus, and yet its gulf-like dynamic difference, which drove Nietzsche quite out of his mind, and half of the world with him? Fornari, with his twin planes or axes, perhaps ends closer to Girard than he wants to recognize. But if the outcome is to raise to the first level of importance the question of what indeed is the mediation of Christ today, the enquiry is more than worth its spectacular effort. To read this book, and to read it again, is to be personally rewarded with the truly postmodern urgency of this question.

Radicale verlossing: Wat terroristen geloven

Erik Buys

Sint-Jozefscollege, Belgium

Beatrice de Graaf, Radicale verlossing: Wat terroristen geloven. Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2021, Pages: 304

In 2018, the work of historian Beatrice de Graaf was awarded the Stevin Prize, the highest scientific award in the Netherlands. Anyone who reads Radicale Verlossing (Radical Redemption) will notice that this award is no coincidence. The title and subtitle of the book leave nothing to be desired in terms of clarity: chiefly de Graaf wants to show what the current generation of jihadist terrorists believes, and what key role a story about radical redemption plays in that belief. In terms of method, she uses a narrative analysis: a critical examination of the testimonies of the terrorists themselves.

As befits a top scientist, de Graaf presents her research in a particularly well-organized manner. In the first two chapters she distinguishes her approach from other methods, introduces some basic concepts, and offers a reader’s guide. The introductory reflections end with the presentation of three panels that make up the narrative of radical redemption: felt deficit, self-chosen surrender and/or struggle, and redemption/reward. A radicalization process based on that narrative, which potentially leads to violence, proceeds in five stages.

The first panel of the story of radical redemption, “felt deficit,” consists of the first two phases of that process. The terrorist believes that the group with which he feels connected is in a state of absolute evil and injustice. He identifies himself with (alleged) innocent victims, without any regard for the possible innocence of those he sees as enemies. This goes hand in hand with the development of a sense of responsibility, resulting in various forms of possible violence: to the extent that the terrorist also considers himself as a malefactor, an act of self-sacrifice as atonement easily comes into focus; to the extent that he mainly accuses others of malice, he will mainly interpret his acts of violence (which may include his self-sacrifice) as a legitimate revenge.

In any case, a narrative of redemption blown up to mythical proportions enables terrorists to distinguish the killing of others and/or themselves as so-called “good, defensive violence” from the “unauthorized violence” (because of a so-called “first aggression”) of a “demonic” enemy. Against this background, the crime-terror-nexus is also notable. De Graaf discusses this in the context of the third panel (“redemption/reward”). She writes: “Radical redemption for young people with criminal records and a surplus of criminal energy is a common phenomenon in the history of terrorism and political violence” (176).

In the context of Islamist terror, de Graaf shows how ISIS used its magazine Rumiyah to justify criminal violence. The self-sacrifice of criminals turned them from “monsters” into “saviors”:

The stories of jihadists-with-a-criminal-record show that it was young people with little to no religious baggage who were particularly drawn to a holy war. They were inspired in no time—often during a stay in prison—to make the switch from crime to terrorism…. The ISIS magazine Rumiyah provided the confirmation, recommendation and substantiation of [the] offer of redemption. According to this digital magazine, it was not only permissible (halal) to shed the blood of the infidels (kufar), but also to take away their prosperity. Practices of deception, in the form of fraud, and theft from infidels, polytheists, and idolaters were praised as legitimate ways to wage jihad…. When a warrior actually lost his life, Rumiyah did not fail to glorify the deceased and to set him up as a martyr. This too was a form of reward: recognition and publicizing of one’s heroic role was an incentive for other jihadists and potential recruits. Here the combination and transformation from criminal to jihadist was memorialized. For example, in the obituary for the late ISIS fighter Abu Mujahid al-Faransi, aka Macreme Abroujui…. Rumiyah praised Abroujui’s criminal skills, elevating them to an ideal and aspiration for all fighters. The late martyr had been a ‘ferocious gangster’ whom everyone feared. With his heroic death, he had not only redeemed himself, but had also served Allah, showing the way to true surrender and conviction. According to Rumiyah, Abroujui had put his violence and criminal talents to use and had purified them in battle: ‘…in their previous lives they participated in the world of theft and gangs, but the violence they committed this time was a form of worship, through which they sought to get closer to Allah—and precisely no longer a way to wallow in excesses, disobedience and corruption.’ The phrase ‘past life’ is crucial here, indicating the intended redemptive move and transformation.” (176-178)

This depiction of the jihadist martyr is reminiscent of many a mythical hero. René Girard characterizes the mythical hero as follows:

A source of violence and disorder during his sojourn among men, the hero appears as a redeemer as soon as he has been eliminated, invariably by violent means. It also happens that the hero, while remaining a transgressor, is cast primarily as a destroyer of monsters.… [T]he hero draws to himself a violent reaction, whose effects are felt throughout the community. He unwittingly conjures up a baleful, infectious force that his own death—or triumph—transforms into a guarantee of order and tranquility.… [T]here are stories of collective salvation, in which the death of a single victim serves to appease the anger of some god or spirit. A lone individual, who may or may not have been guilty of some past crime, is offered up to a ferocious monster or demon to appease him, and he ends up killing that monster as he is killed by him” (Violence and the Sacred, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1972, 87).

Important in the third panel of the narrative of radical redemption is not only the act of violence itself (the fourth stage of the process), but also its validation by a constituency (the fifth and final stage of radicalization). That constituency must recognize the act of violence as part of a larger struggle between good and evil. Before it gets to that point, de Graaf connects the main push factors of radicalization in the second panel of the radical redemption story—the personal context of drastic experiences and the accompanying intense emotions and desires—with the pull factors of organizations that situate personal experiences in a broader historical, geopolitical, and meaningful perspective.

De Graaf uses the testimonies of terror convicts, whom she has interviewed herself, to convincingly support the three panels of the radical redemption story. This is done in chapters four, five and six. Prior to that, the third chapter contains stories of terrorists from the first three major waves of modern terrorism, as identified by David Rapoport from the late nineteenth century onward: anarchist terrorism, anti-colonial terrorism, and new left terrorism.

In doing so, de Graaf illustrates two important issues. First, she makes clear that the traditional characterization of terrorist ideologies by means of the so-called Three Rs—Revenge, Renown and Reaction—should, if necessary, be supplemented by a fourth R: the positive offer of a Story of Radical Redemption. It is a bit of a shame that she does not incorporate the notion of the Myth of Redemptive Violence, as developed by theologian Walter Wink (1935-2012). That would allow for an inside critique of theological narratives of redemption, which distinguishes a theology of nonviolent love and redemption from a theology of violent redemption. But perhaps that is too much to ask for within the scope of this book, and it is rather up to theologians to do so, especially also as an aid to deradicalization processes.

With her historical overview of modern terrorism in light of the radical redemption motive, de Graaf demonstrates that a narrative of radical redemption need not be purely religious. So secondly, she illustrates what she already emphasizes in her introductory reflections: “By bringing up the motive of radical redemption we transcend the debate between religious versus political motivation…. Whether a redemption story is political-ideological or religious in nature is a matter of supply, scale and gradation rather than psychology. Stories may differ, human biology and psychology remain the same” (33).

A few pages further, she adds:

Is redemption only a concept that can exist within religions? No. Within the context of sociology and cultural anthropology it is now widely recognized that the search for meaning, the formulation of goals that transcend one’s own immediate life horizon, is inherent in all human cultures. Man is a religious being, for better or worse; almost everyone believes in a higher purpose (transcendent or immanent) and has something to show for it. Our ‘altruistic gene’ that leads to community involvement and fundraising also brings with it exclusion and the stigmatization of perceived enemies of the community…. The question is not whether redemption only plays a role in religious contexts, but how the social experience of redemption is shaped. How is redemption standardized and prescribed (and by whom)? What does the alleged debt or penalty consist of, who is to settle it, and in what way? So it matters quite a bit how the idea of radical redemption is fleshed out and validated by an associated community and worldview” (38-39).

In short, the redemption motive may also play a role in secular forms of terrorism. What is striking, however, is that it does not always play a role, even if terrorist acts are committed by religious people. This is shown in the seventh chapter, in which de Graaf presents research in several control groups. She sees the redemption motive in fighters from a group like Boko Haram, while she finds it hardly at all in fighters from right-wing extremist networks (DTG Enschede) or from Syrian resistance groups. Rightly she warns: “Among the fighters of Boko Haram, a sectarian ideology, strong community, as well as mutual control and assessment do exist. Whereas with Syrian members of armed militias, even if they are Muslim, we must be very careful not to be too quick to point to religious or terrorist motives, with members of jihadist groups like those in Africa we must be careful not to link radicalization processes too quickly to major underlying causes such as poverty or deprivation” (254).

In this chapter, de Graaf does not fail to address the parasitic nature of right-wing extremist terrorism. By committing violence, some right-wing extremists actually imitate the violence of their enemy, paradoxically and tragically continuing the evil they thought they were destroying: “We could argue that the right-wing extremist terrorists practiced a form of idiosyncratic, parasitic terrorism. They developed their own perversely unique, right-wing extremist worldview, and parasitized on existing fears in society of ‘Islam’ and/or of ‘black danger.’ One could perhaps argue that every major wave of ideological terrorism, be it anarchist, ethnic-social, leftist-revolutionary, or holy, jihadist terrorism, was accompanied by a reaction of ‘parasitic terrorism’—terrorism that sucks up the energy of and fears about a prevailing wave of radical violence and uses it to destabilize society through its own attacks (of opposite ideological nature)” (234).

After the chapters that address her inductive method, the eighth chapter presents de Graaf’s “Grounded Theory” of Radical Redemption, a deductive frame of reference for further research. Moreover, she critically evaluates her research in the subsequent ninth and penultimate chapter. Variables in each panel that make up the triptych of radical redemption (again: felt deficiency, self-chosen surrender and/or struggle, and redemption/reward), ultimately result in ten profiles into which the interviewed terror convicts more or less fit: meaning-seeking zealot, penitent zealot, avenging zealot, political zealot, meaning-seeking altruist, penitent altruist, political altruist, meaning-seeking avenger, meaning-seeking follower, and armed opposition/self-defense.

Of course, the concrete environment in which a terror convict was raised is also important, but today variables in context at the macro, meso, and micro levels are quite often overshadowed by a unifying, globalized virtual context. Wherever terrorists may be, they draw on the same ideologies found on the Internet.

De Graaf sees possibilities for breaking the cycle of radicalization mainly in forms of criticism by one’s own supporters. Disagreement within one’s own ranks is important. If people in one’s own group do not (no longer) validate acts of terrorism, the temptation to choose armed struggle diminishes. In addition, de Graaf concludes that deradicalization in the context of the violent redemption motive almost automatically happens when perpetrators go through the entire cycle (the five phases) of the radicalization process. Indeed, the narrative of violent redemption can rarely live up to the high expectations it creates: “In other words, the redemption narrative succumbs to its own ontological inconsistencies” (275).

As a result, the likelihood of recidivism is also low. That said, more preventive measures should be taken in parenting and education. As for the reintegration of terror convicts, de Graaf sees an important role for religious communities. The example of churches in Africa inspires in that regard: “A special role is played by churches and religious communities, particularly in Africa, where they are often the last remaining institutions that are still willing and able to visit detainees, for example through the chaplains of the Roman Catholic Church in northern Cameroon and Nigeria. There the conditions in the prisons are so wretched that the churches are the only organizations still willing and able to do something for imprisoned convicts of terrorism” (288).

Apparently, the churches there play a major role in the process of forgiveness, a vital step on the road to eventual reconciliation. Perhaps forgiveness is the trace of a true transcendence? That trace leaves the path of perfectionism and fear of failure, of strident self-condemnation and condemnation of others to which some, whether in the form of compensatory (suicidal) terrorism or not, fall victim in the context of “secular presentism” (318).

Beatrice de Graaf has not only written an excellent book in scientific terms. With her concluding reflections she also sets the contours for further philosophical and even theological discussion.

Triple terrorist alert by Wiel Eggen (Netherlands)

Buys’ well-focused Girardian review of de Graaf’s analysis of the redemptive myth behind Muslim terrorism should alert us to a double Christian similar idiom having come to a height in the state-terrorism of Putin’s reckless Ukraine adventure. Girard has recognised not only Muslim relapse in such violence but also the radicalism driving the sacrificial reading of Christ’s cross to ugly excesses throughout Europe’s history, feeding even into contemporary forms of evangelicalism. The Paulinian theologia crucis having been mixed with Platonism and metaphysics not only led to the medieval religious terror and anxiety that urged Luther to seek salvation in pure faith. But the Protestant three solas carried on the same metaphysical idiom despite a secularist twist feeding into Kant’s ethical formalism and Hegel’s master-slave discourse, with their twin-offspring of fascism and communism, which Nietzsche diagnosed as fruit of dark ressentiment of Biblical ilk. We see this twin rising to an ugly climax in Putin’s combat, which too few have seen emerging, even when in 2010 he committed the vilest of crimes by planned State-terrorist as he blew up the Polish presidential plane in the air just before landing near Smolensk carrying President Kaczynski and 95 top-officials. That EU alarm bells failed to ring, then, but that rather Tusk was made their president, despite his electoral defeat in Poland for letting Putin get away with this terrorism, can only be explained by a blindness for the redemptive myth running through the political theology. *

When Serres hailed Girard as a revolution in the human sciences, he pointed to a novel instrument for analysing and unnerving the forms of radicalism, which root in a triple deviation in the biblical hermeneutic variants. The fact that Putin leans on an anti-ecumenist trend in Orthodox faith, which earlier drove Milosevic Serbia to its terror, must be discerned as the fruit of a hermeneutical line that differs profoundly from the theologia crucis undergirding Western sacrificial metaphysics, which arguably culminates in the Hegel-Marx centralism and ultimately hinges on the vertical rather than horizontal reading of Eden-episode. Exegetes distinguish between the Synoptic-Paulinian line varying starkly from the Johannine one, which rather inspired the Orthodox vision of the church. The intricacies of this hermeneutic split are now being investigated along with a third line that has been given prominence recently. While the Gospel of Mark harmoniously combines the former two, as it uses a version of atonement-theology rooted in Isaiah’s new temple ideal, the third line (of the older Q-source retaining mainly wisdom-sayings of the Lord) mark chiefly the two other synoptic texts. The latter seems to have inspired Mohammed’s reading of Jesus’ prophetic message which he separated rigorously from the crucifixion’s myth of atonement. These three hermeneutic lines have each led to a redemptive myth with respective forms of terrorist radicalism. Girard encourages us to discern and unnerve this in what I would call a triadic synodal ecumenism in which they can be harmonised again. If ever, this challenge is an urgent task for which Girard offers us the tools.

• The file on Putin blowing up Kaczynski’s plane and Tusk’s connivance with it makes grim reading in the light of what followed.