In this issue: tributes to René Girard and Wolfgang Palaver, reflections on violence in Colombia and Israel, new publications, forthcoming events, and three book reviews.

Contents

Musings from the Executive Secretary: Nikolaus Wandinger, Celebrating a Dear Colleague

Editor’s Column: Curtis Gruenler, Gatherings, Publications, and Videos

René Girard Centenary, Paris / Avignon, December 14-17, 2023

The Porch Gathering, Montreat, North Carolina, March 7-10, 2024

Theology & Peace Annual Gathering, Chicago, June 10-13

COV&R Annual Meeting, Mexico City, Mexico, June 26-29, 2024

Letter from… the Negev: Mark R. Anspach, Many of the Victims of the Hamas Attack Were Pacifists

Curtis Gruenler, Be Not Conformed: René Girard at 100

Martha Reineke, René Girard 100 Year Memorial Concert

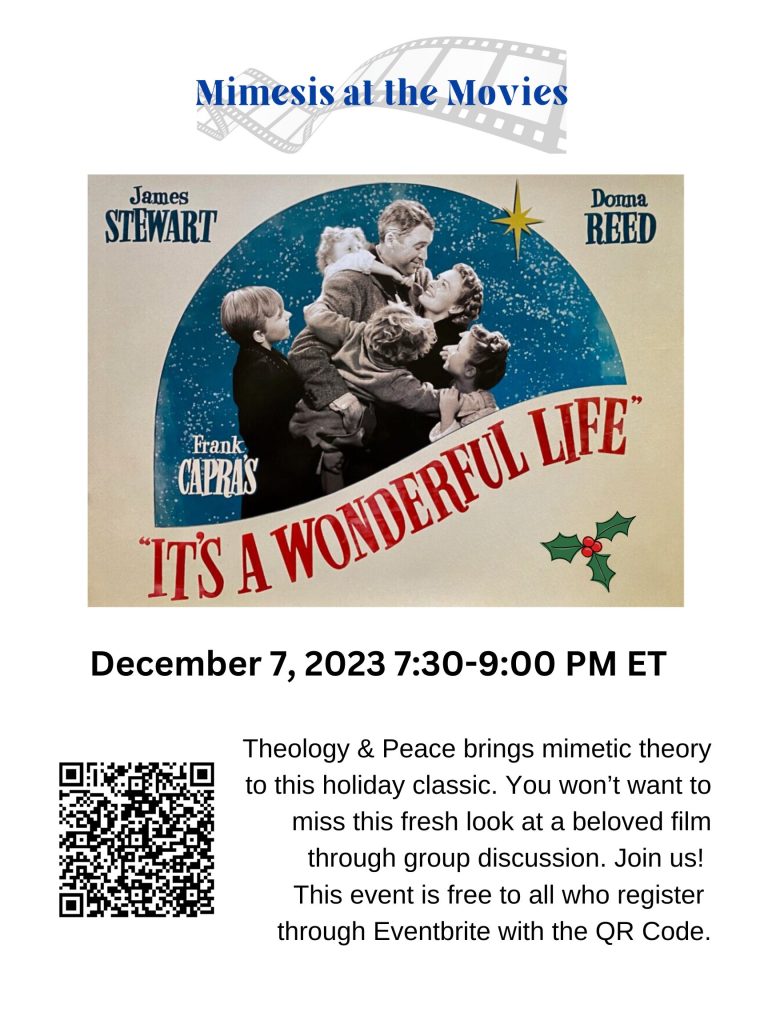

Commentary: Andrew McRae, What George Bailey Gave and What George Pratt Received

Scott Cowdell, Unbecoming a Priest: A Memoir by Anthony Bartlett

Musings from the Executive Secretary

Celebrating a Dear Colleague

Nikolaus Wandinger

On October 6, the Theological Faculty in Innsbruck celebrated their esteemed colleague Wolfgang Palaver, who gave his farewell lecture before entering his retirement. All who know Wolfgang also know that retirement for him will not mean saying goodbye to academia and research but being freer to pursue those avenues of research that he deems most interesting.

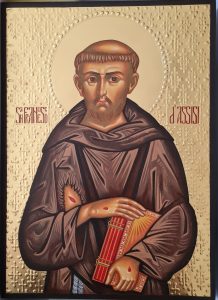

Wolfgang gave a lecture, “Being Brothers and Sisters despite Sibling Rivalries: Preconditions for Democracy and Peace,” in which he developed thoughts for a culture that allowed for controversial debate—as a prerequisite for democracy—borne by the conviction that one’s opponents in the controversy are one’s equals. He emphasized that a narrowing of this sibling equality into merely brotherhood easily deteriorates into a patriarchal machismo. What was needed was a kenotic renunciation of the greed for power and possessions. After his lecture, Wolfgang was presented with an icon of St. Francis of Assisi and with a festschrift entitled Politik des Evangeliums / Politics of the Gospel, containing essays in German and in English. It was wonderful that among the English contributions are an introductory greeting by Martha Girard and essays by several long-standing COV&R members (for a complete list of contents and free download of the work, go here).

While writing this piece for the Bulletin, a comparison almost forces itself into my mind: Wolfgang seems to me like a one-person colloquium on violence and religion. Not that he would only converse with himself—far from that—but that he is so intent on conversing with different experts in various fields that he as a person is almost like COV&R as an organization. Wolfgang is a Catholic theologian, specializing in Catholic social teaching and ethics of peace. His interests and expertise, however, go far beyond that. He sees how literature, psychology, philosophy, computer science, economics, interreligious dialogue, and, of course, politics are all related to that. Wolfgang’s strength is that he connects all these fields and more and probes them about the core questions that interest him. If COV&R, like him, continues to draw on the particular fields of expertise of its members, yet also goes on to look beyond each of them and combines their perspectives and insights into something bigger, so that each learns from the others, we are on a good way as an organization.

If we heed Wolfgang’s admonition to respect the opponent in an argument as an equal, with whom—despite all rivalry—we are brother or sister, this will continue to enliven our discussions but sustain the friendship that so many enjoy within COV&R. Wolfgang and I share a deep respect for first COV&R President Raymund Schwager; therefore I dare suggest that we might even go a step further than just respecting an opponent as our equal as brother or sister. Schwager advocated for integrating one’s opponent’s legitimate concern into one’s own standpoint, thereby enabling a good and fruitful outcome to a controversy.

It is true that we do not have an objective criterion for when a concern is legitimate and when it is not. But the mere acknowledgement that there might be a legitimate concern in a standpoint opposed to mine will help me to watch out for it and maybe discover it. Wolfgang was an ardent scholar of René Girard and is an acknowledged expert in mimetic theory. Yet, he never went about it in a “dogmatic” way but truly accepted all three elements named in the colloquium’s objective, namely “to explore, criticize, and develop the mimetic model of the relationship between violence and religion.”

One last tentative comparison: In his characterization of Wolfgang Palaver, our Dean, Wilhelm Guggenberger, likened him to a squirrel that was stocking up on nuts for the winter, with the slight difference that Wolfgang was not gathering nuts to survive winter but literature to expand his knowledge. At COV&R we are doing the same: producing, gathering, storing thoughts in writing and other media and making it available to whoever is interested. I am confident that we will continue to do so—and hopeful that Wolfgang will still be available for us with his advice, his wisdom, and his calm presence.

One last tentative comparison: In his characterization of Wolfgang Palaver, our Dean, Wilhelm Guggenberger, likened him to a squirrel that was stocking up on nuts for the winter, with the slight difference that Wolfgang was not gathering nuts to survive winter but literature to expand his knowledge. At COV&R we are doing the same: producing, gathering, storing thoughts in writing and other media and making it available to whoever is interested. I am confident that we will continue to do so—and hopeful that Wolfgang will still be available for us with his advice, his wisdom, and his calm presence.

Editor’s Column

Gatherings, Publications, and Videos

Curtis Gruenler

This issue features two articles by COV&R members about current events: Roberto Solarte’s piece about reconciliation in Colombia and Mark Anspach’s piece about pacifist victims of the October 7 attack by Hamas. Mark’s piece is longer than what the Bulletin usually publishes, but its remarkable gathering from published sources of a story that has not to our knowledge been told, along with analysis from a Girardian perspective, makes it both important and urgent. For another, more hopeful look at the sort of things that go underreported, I appreciated Thomas Friedman’s column in the November 22 New York Times, “The Rescuers.” Susan Connelly, author of East Timor, René Girard and Neocolonial Violence: Scapegoating as Australian Policy, has also applied mimetic theory to the current violence in “Enemy Twins: Israel and Hamas Unite to Massacre Innocents.” The Bulletin welcomes comment on its articles and reflections on events and issues of interest from all COV&R members.

There will be more information about next summer’s annual meeting coming to COV&R members soon by email, including the call for papers and instructions for reserving lodgings at a discount. For reports on events this fall celebrating the centenary of René Girard’s birth, and an announcement of one more later this month, see below.

A 20% discount is available to COV&R members for the seven most recent volumes in Michigan State University Press’s Studies in Violence, Mimesis & Culture and Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory, up through Violence and the Mimetic Unconscious, volume 2: The Affective Hypothesis by Nidesh Lawtoo. The others are: Scott Cowdell’s Mimetic Theory and Its Shadow: Girard, Milbank, and Ontological Violence; Alterity by Jean-Michel Oughourlian, translated by Andrew McKenna; Violence and the Oedipal Unconscious, volume 1: The Catharsis Hypothesis by Nidesh Lawtoo; The Time Has Grown Short: René Girard, or the Last Law by Benoît Chantre; Toward an Islamic Theology of Nonviolence: In Dialogue with René Girard by Adnane Mokrani; and Jean-Pierre Dupuy’s How to Think about Catastrophe: Toward a Theory of Enlightened Doomsaying. The 20% discount is also available for pre-orders of two books due out early next year: The World of René Girard, interviews conducted by Nadine Dormoy in 1988 and translated from French by William Johnsen, and Cormac McCarthy: An American Apocalypse by Marcus Wierschem. In addition, a 30% discount is available on selected titles from the backlist with a purchase of three or more. For more information, please see this page in the members section of the COV&R website. The same page includes a discount code for ordering through Eurospan, which has better shipping rates when ordering from Europe than ordering directly through MSUP.

The current COV&R YouTube videos are now listed on a page on the website. It’s an extensive collection, including several separate playlists. The most recent addition is a professionally produced reprise of a panel on “Religion, Madness, and Mimetic Theory” from last summer’s COV&R meeting in Paris. Hosted by Joachim Duyndam, this panel’s exploration of various relationships between religion, madness, and mimetic theory starts from the life experiences of the two main presenters Michael Elias and Berry Vorstenbosch. Both were able to overcome their psychoses with the help of insights from mimetic theory.

Julie and Tom Shinnick will be hosting a new read-aloud-and-discuss Zoom group on The Scapegoat by René Girard, weekly on Monday nights at 6:30-8:00 Central Time starting January 15. Julie writes: “This is the first book we will have read that is actually by René Girard himself. The Scapegoat gives a good overview explanation of Girard’s theories. It includes Girard’s beautiful and illuminating discussions of several key biblical texts: the Gerasene demoniac, the beheading of John the Baptist, the gospel Passion narratives, Peter’s denial, etc. Used copies of the book are available on amazon.com and abebooks.com (new ones also, but the used ones cost less). For people unfamiliar with the read-aloud format, we take turns reading aloud from the text, stopping for discussion and comments when anyone has a question or comment to make, so progress may seem slow. (Please note: listeners who do not want to read aloud are very welcome.) The read-aloud format provides an opportunity for rich discussion which members have greatly appreciated. It also helps readers and listeners slow down from our busy lives for a weekly period of reflection in a small community. We only read 10-20 pages a week, so it is easy to catch up if people have to miss a session or two. We record each session for anyone who misses a meeting and wants a copy. The recordings are private, and only sent to members who request them. About a week before the meeting I’ll send out a link for the zoom.” If you are interested, please email Julie.

The commentary below on the classic Christmas film “It’s a Wonderful Life,” and the short story on which it is based, also serves as an invitation to participate in the online discussion Mimesis at the Movies hosted by COV&R’s partner organization Theology & Peace. Note also that Theology & Peace has rescheduled its next annual gathering for June 10-13, 2024.

For a children’s book informed by Girardian insights about human history, see Cory and the Seventh Story by Brian McLaren and Gareth Higgins. The seven stories are also the focus of the latest season of McLaren’s podcast Learning How to See, produced by the Center for Action and Contemplation.

The podcast EI Weekly Listen recently featured a reading of an article by Wolfgang Palaver on violence and religion. Harper’s Magazine published an extended, rather quirky and personal, but nonetheless engaging and substantial essay, “Overwhelming and Collective Murder: The Grand, Gruesome Theomries of René Girard,” occasioned by the new Penguin Classics anthology of Girard, All Desire Is a Desire for Being, edited by Cynthia Haven. The September 13 issue of L’Express includes a review of Benoît Chantre’s new René Girard: Biographie.

If you have news of publications or events, or would like to submit a commentary, please contact me.

Forthcoming Events

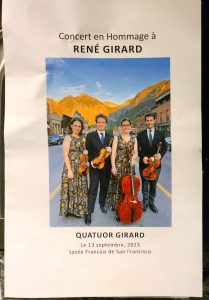

Hommáge á René Girard

á l’occasion du centenaire de sa naissance

Paris / Avignon

December 14-17, 2023

This series of events in honor of René Girard on the centenary of his birth will feature two concerts by the Quatuor Girard and the Orchestre national Avignon-Provence, one at the Collège des Bernardins in Paris on December 14 and the other at the Palais des Papes in Avignon on December 17. The Paris concert will be followed the next day by a symposium at the Collège des Bernardins on the theme “René Girard, lecteur de l’écriture” with the participation of, among others, Benoît Chantre and Wolfgang Palaver. Further information is available here.

The Porch Gathering

Montreat, North Carolina

March 7-10, 2024

James Alison and Julia Robinson Moore are both featured speakers at the “festival-meets-retreat” dedicated to “transformative storytelling.” Information and registration is available here.

Theology & Peace Annual Gathering

Chicago, Illinois

June 10-14, 2024

Plenary speakers will be Father James Alison, priest, author, and theologian and Adam Ericksen, pastor of Clackamas United Christian Church, OR, and Executive Director of The Raven Foundation.

James Warren will be presenting an explanation of mimetic theory. Chaplain Ellen Corcella will share her explorations of the interconnections between faith, spirit, trauma and resilience that have revealed ways we can further embrace our faith and enhance our resilience.

The meeting will be held at the Casa Iskali Our Lady of Guadalupe Campus located outside of Chicago. For complete information and registration, see the Theology & Peace website.

Desire among the Ruins:

Mimesis and the Crisis of Representation

COV&R Annual Meeting

Mexico City

June 26-29, 2024

Sponsored by Universidad Iberoamericana and hosted at the Colegio de San Ildefonso, COV&R’s annual meeting is being organized by board member Tania Checchi.

Filled with palaces and museums, Baroque churches and Art Deco buildings, Mexico City’s architectural history spans more than half a millennium, and new archeological discoveries are being made almost every year. San Ildefonso is located in the heart of Mexico City, just behind the Cathedral and next to the archeological site of what was the most important Pre-Hispanic religious center, Templo Mayor. Its situation at the crossroads of these two major cultural landmarks makes it the ideal venue for our conference.

The theme, “Desire among the Ruins: Mimesis and the Crisis of Representation,” opens up a dialogical and critical space for discussing what kind of motives, aspirations, and even hopes are inscribed into our need for images, taking into account from a mimetic point of view not only their sacrificial origin and their concomitant problematic status, but also their almost infinite capacity for transformation and renewal. The “ruins” of the title evoke both the actual archeological sites that will surround us during the conference, with their archaic echoes and demands, and the actual “ruin of representation” announced by Levinas à propos the crisis of traditional epistemologies and, most importantly, the crisis of meaning experienced from the 20th century on. Given this situation, we must ask along with René Girard: is desire condemned to walk among the ruins of its mimetic failures or can it open up to the truly desirable, an alterity whose frailty no violence can reduce or silence? And finally, can images be the vehicle of this conversion?

Mexico City offers comfortable accommodations at a wide range of prices. Mexican cuisine was declared a Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010 by UNESCO and Mexico City’s array of all Mexico’s traditional food as well as experimental new Mexican cuisine will make for an unforgettable cuilinary experience.

A full call for papers will be sent to COV&R members soon. Proposals related to the conference theme as well as other topics pertaining to mimetic theory will be welcome from anyone. Further information will be available on a conference website by early 2024, including details about travel, accommodations, travel grants, the Raymund Schwager essay competition, plenary speakers, and special programs taking advantage of the cultural riches in and around Mexico City.

Letter from… Bogotá

From Public Apologies to

the Difficulties of Granting Forgiveness

Roberto Solarte

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana

Editor’s note: This article was translated and adapted for the COV&R Bulletin by Carlos Mora, Rubén García, Juan Contreras, John J. Estrada, and Roberto Solarte. It originally appeared here. The Bulletin welcomes commentary on current events from all COV&R members.

These days, everyone on the planet is witnessing in terror the war that has broken out between Hamas and the state of Israel. Just as in the case of Russia’s war against Ukraine, one can always argue “good reasons” for murdering defenseless civilians. The mass murder of children has placed us before an apocalyptic panorama, where many nations have an interest in asserting themselves against others, even if they destroy humanity in the attempt. How can we address this serious situation from mimetic theory when we are in the global south?

Nevertheless, an event in Colombia opens some hope for us. But this hope does not shine enough, given the limitations that make our institutions true mechanisms of exclusion, secretly based on violence. During the presidential administration of Uribe (2002-2010), 6402 young people were killed and presented as guerrillas killed in combat. These killings are known as “false positives.” Nineteen of these youths lived in Soacha, the municipality south of Bogotá that has served as a point of arrival for hundreds of thousands of peasants who lost their land and were forced to be displaced.

The act of “public apology” to the relatives of the wrongly named “false positives” of Soacha took place on October 3, 2023, in a small and reserved space in the Plaza de Bolivar, in downtown Bogotá. Most of these family members are the mothers of the murdered youths. It was done in “compliance with ACT 033 (2015) of the Truth and Responsibility Recognition Chamber of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and the orders established by” other courts (Mindefensa, 4/10/2023). It was a long and strenuous process because some legal actions were ignored or obstructed during the presidential administrations of Santos (2010-2018) and Duque (2018-2022). On behalf of the state, the current government assumed the responsibility of asking for these “apologies” in public, for the acts committed during Uribe’s administration under the “ministerial directive 029 of 2005”, signed by the Minister of Defense in that administration, Camilo Ospina, to “regulate the payment of rewards, avoid misunderstandings on the part of the Public Force and give transparency to the incentive policy” (El Espectador 11/1/2008).

The act of “public apology” to the relatives of the wrongly named “false positives” of Soacha took place on October 3, 2023, in a small and reserved space in the Plaza de Bolivar, in downtown Bogotá. Most of these family members are the mothers of the murdered youths. It was done in “compliance with ACT 033 (2015) of the Truth and Responsibility Recognition Chamber of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and the orders established by” other courts (Mindefensa, 4/10/2023). It was a long and strenuous process because some legal actions were ignored or obstructed during the presidential administrations of Santos (2010-2018) and Duque (2018-2022). On behalf of the state, the current government assumed the responsibility of asking for these “apologies” in public, for the acts committed during Uribe’s administration under the “ministerial directive 029 of 2005”, signed by the Minister of Defense in that administration, Camilo Ospina, to “regulate the payment of rewards, avoid misunderstandings on the part of the Public Force and give transparency to the incentive policy” (El Espectador 11/1/2008).

This policy was continued by the next minister, Juan Manuel Santos, who served for almost three years in the ministry, from which he only resigned when he was called to trial for his political responsibility in the so-called forced disappearances of young people. It is not surprising that in his government, when he signed the peace agreement with the FARC-EP guerillas, there was no progress in the fulfillment of these legal requirements. The government of Duque blocked this public obligation by focusing all its efforts in destroying the peace agreement. Duque and his former Ministry of Defense, Molano, were accused of the crimes committed by the state forces against young people during the National Strike and the Social Outbreak of September 2020. Nor is it strange that Álvaro Uribe uses his media resources to deepen the harm on the victim’s families and to insist in the denial of his responsibility.

In fact, the current government did not limit itself to excusing the state, but its representatives went ahead asking for forgiveness. In the words of the current president of Colombia, Gustavo Petro: “As president of the Republic of Colombia, of this one which is a popular government, I allow myself to ask for your forgiveness, mothers.” In the same sense, the Minister of Defense, Iván Velásquez, pronounced: “On behalf of the State, the current Ministry of Defense, the Military Forces, the National Army, we ask forgiveness from you, mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, husbands, children, relatives and the entire population for the reprehensible acts of forced disappearance and which were later presented as casualties in combat. We ask forgiveness for these crimes that shame us before the world.” The same tone was followed by General Ospina, current commander of the army, who maintained that the institution must become legitimate in “the protection and respect for life,” as well as in preserving human rights and international humanitarian law; he acknowledged that the military institution caused the death of the young people of Soacha and, therefore, said, “we offer our heartfelt and sincere apologies and ask, with the humility that characterizes a soldier of the homeland, for forgiveness.”

The central aspect of “public apologies” was the act of apology itself, which consisted in honoring and dignifying the victims’ names and recognizing that they were innocent civilians. These young men were leading the ordinary lives of the youth of Soacha, where many of the families are victims of forced displacement. They were educated in the effort to move forward and, in their innocence, were seduced by the need to obtain a job. However, they were hoodwinked and the promise of a better life quickly turned into their disappearances and murders, which were neither false nor positive.

They became victims of the state forces because of the double mentality of stigmatization against the youth of the poorest sectors and the dangerous custom of “social cleansing.” On one side, the order of the military commanders was to implement a kind of “purification” of those who are potentially dangerous, but they applied it against youths from the poorest neighborhoods, assuming that they were dangerous because of their social condition. The paradox here is that most those who committed these crimes are, precisely, young people from similar sectors, pressured by the demands of their high commands. And these, in turn, acted at the service of avarice, which “leads to murder, leads to killing,” as President Petro said: “They killed those young people because they wanted to return to government, because if they did not remain in power, the business would be over.”

But forgiveness remains incomplete, because those who gave the order refuse to recognize it, including the moral and political responsibility that corresponds to former Presidents Uribe and Santos. Also, because several media echo the discourses that justify the state’s violence, generating a society in which a huge block of people believe that it is legitimate to kill those who have been unjustly stigmatized as guerrillas, drug dealers, hitmen, drug users, delinquents, criminals, in other words, young people from poorest sectors. Also, because several of the institutions of justice hide the facts and make it difficult to find the truth. For this reason, several of the mothers and family members have refused to give their forgiveness and continue to demand that those who gave the orders assume their responsibility.

Paradoxes of human rights and the public sphere

Ever since the military and police forces began to be accused of violating human rights, in the dark days of the “security statute,” at the end of the ’70s, the response of the state has been to educate armed forces in human rights; this continues to be the state’s reaction. In the shadow of this compromise, the paramilitary groups, whose history is public knowledge, were set up. In the testimonies gathered by the Truth Commission, paramilitary violence was always protected by the military and police forces.

Human rights are the ethical core of the rule of law. The state is organized to guarantee and defend them. The latter is done through the control and exercise of “legitimate” armed power. The problem in Colombia, as in any state that understands its internal conflicts in terms of friends and enemies, is that human rights have become ineffective, because the perpetrators are obliged to comply with them, but only understand that they fulfill their duty by violating them, killing civilians.

Something that can symbolize this paradox is the double fence that prevented access to the public event in Bolivar Square. The democratic rule of law, even in a leftist government, cannot fail to act per its double core: it cannot defend human rights except by exercising violence, and, therefore, by violating human rights with justification such as those we have heard from the mouths of those responsible for these state crimes. In the same way, the actual government does not manage to make a public act that has the name it should have: request for forgiveness by the representatives of the state to the victims of state crimes. It can only manage to make a closed act, public only in the sense that the media was present, and that the long ceremony was transmitted live. Then, the state only reaches, in the best of its versions, a virtual public, because the participation in the square was excluded beforehand. The democratic state, guarantor of human rights, only manages to carry out a public act excluding the public. The reasons, as always, sound very valid: the protection of these victims threatened by the same powerful people who took away their relatives.

These paradoxes have no resolution within the logic of the rule of law, guarantor of human rights through the “legitimate exercise of violence.” To seek alternatives, we can propose to move towards a society where conflicts can be resolved through dialogue, as President Petro proposed to the mothers of Soacha. But the rule of law will always contain that unconfessable, invisible core of victims that it necessarily produces. So, perhaps, what we can do is to propose to move forward in dismantling the mechanisms that produce victims in all our relationships and ways of being with other people, exposing these mechanisms without producing new victims. It is a matter of building a society that does not generate more victims of any kind. As René Girard taught us: “Sooner or later, either humanity will renounce violence without sacrifice or it will destroy the planet” (Battling to the End, p. 21).

Letter from… the Negev

When Pacifists Are Victims

Mark R. Anspach

Editor’s note: The Bulletin welcomes commentary on current events from all COV&R members. To view the footnotes, click on “Read More” then click on the footnote number.

They descended from the sky like angels of death. They rode on paragliders and were joined by swarms of armed men in cars. One of their first targets was Netiv HaAsarah. The wall around the village displayed a dove and the words “Path to Peace” above a colorful mosaic. Over the years, thousands of visitors from around the world had added tiles to the mosaic as tokens of their hope for peace.1 But these visitors were different. They were bent on murder and left a score of dead inhabitants in their wake.

Netiv HaAsarah, a moshav or agricultural collective, was originally located in the Sinai peninsula. After Israel returned the Sinai to Egypt for the sake of peace, the residents packed up and left, moving to a new site in the Negev desert. The Negev is where some 1200 Israelis were killed by Hamas on October 7.

We are accustomed to hearing about conflict between Palestinian Arabs and aggressive, right-wing West Bank settlers. It is important to note that the victims this time were not settlers in disputed territory. The Negev is inside the Green Line; it has been part of Israel since 1949. In fact, the stretch of desert bordering the Gaza Strip had already been assigned to the Jews in the 1947 United Nations partition plan.

Moreover, many of the communities attacked by Hamas were kibbutzes known for their left-wing politics, and many of the victims were pro-Palestinian peace activists. The highest death toll was at a desert rave devoted to love and harmony where young people danced under a giant Buddha statue. They were not killed for being obstacles to peace or colonizers. They were killed simply for being Israeli Jews.

In this article, we tell some of their stories through the words of the survivors. We then propose a new explanatory framework for understanding the massacres in the light of René Girard’s anthropological theory.

The Supernova music festival

Raif Rashed, an Israeli Druze Arab who lives in Hackensack, was visiting family in Israel when his younger brother asked him to help cater the annual music festival. “It’s peace-loving people who come to enjoy electronic music,” Rashed told the New Jersey Record. “We know all of them. They are friendly. They come to eat with us. We spend the night talking with them and joking around.”

In keeping with the festival’s pacific spirit, the organizers prohibited attendees from bringing weapons. When the terrorists arrived with automatic rifles and rocket-propelled grenade launchers, the victims were defenseless. “They came to kill us and we had nothing,” Rashed said.2 Another survivor voiced similar sentiments in an interview with Tablet. He remembered hiding with friends in a bush surrounded by shooting: “I had nothing on me.” One thought ran through his mind: “The only thing I want is a weapon. I want something to protect us.”3

Rashed fled with others into a nearby forest and watched the rampage unfold from behind the trees. He could make out some of what the attackers were saying in Arabic: “I hate them! I hate them!” or “Get into the truck!” He heard a woman beg for her life while the terrorists joked and laughed at her. “Then, they pulled her by the hair and shot her in the head. I saw them beating kids with hammers,” Rashed recalled. “I saw them lynching kids.” After many hours, when Rashed finally ventured out of his hiding place, he was relieved to see an Israeli tank roll in.4

Ismail Alqrinawi, one of four Bedouin cousins who rescued dozens of festival goers by making numerous trips back and forth in a jeep, says he is haunted by flashbacks of stacked-up corpses.5 As for Raif Rashed, he is still struggling to comprehend what happened. “Why did they come to kill kids? They were only 20, 25 years old. I never hated anyone… I speak three languages and we all get along. Here, because they are Jews and they speak Hebrew they have to die?”6

Kibbutz Nir Oz

Irit Lahav survived the massacre at Nir Oz by barring the safe room door with a vacuum cleaner and the oar from a rowboat. Lahav describes herself as a pro-Palestinian peace advocate. “My mother used to tell me I was more Palestinian than the Palestinians themselves,” she said. She was one of many volunteers who drove Gaza residents to hospital appointments in Tel Aviv. Back in 2005, when Israel pulled out of the Gaza Strip, she had been sure things would improve. “They got what they want. They got their own land. Finally peace will come,” she thought. “And I was totally shocked. Two months later, missiles were landing on us.”7

Two abductees from Nir Oz, Yocheved and Oded Lifshitz, were among the kibbutz’s founders. Yocheved was one of the first hostages to be freed while Oded at this writing is still missing. Hamas rousted Yocheved, 85, from her bed, detaching her from her oxygen device. She said after her release that she had been treated well in captivity but noted that Hamas gunmen had beaten her with sticks on the way to Gaza and then forced her to walk miles to her prison in damp subterranean tunnels. “I went through hell,” she remarked. When she was freed, she nevertheless shook the hand of one of her captors and told him “Shalom.”8

Yocheved’s husband Oded Lifshitz, 83, a leftwing journalist, learned to speak Arabic and strove to build good relations with the kibbutz’s Arab neighbors. “My father spent his life fighting for peace,” said his daughter Sharone. Noam Sagi, the son of another hostage, said that “Sharone’s dad had medals from the PLO” honoring his efforts on behalf of Palestinian Arabs. Oded Lifshitz also helped Bedouin nomads of the Negev Desert recover lost land. Like Irit Lahav, Oded Lifshitz regularly drove patients from Gaza for treatment in Israeli hospitals. Then terrorists from Gaza came for him.9

Ada Sagi, 75, a widowed peace activist, was also kidnapped from Nir Oz (she was freed on November 28). The Associated Press writes that Ada was born in Tel Aviv but chose to move to a kibbutz because of “the ideals of equality and humanity on which the communal settlements were built.” Ada’s son Noam declared at a London press conference, “My mother’s mission was to build bridges through communicating.” She learned Arabic and went on to teach the language to other Israelis in order to foster better relations with their Arab neighbors. “Maybe I’m a fantasist,” Noam Sagi said, “but my hope is that they realise that they actually kidnapped 80 people from this community who are all peace activists.”10

Noam returned to his childhood home with a reporter and was disturbed to see a trail of blood leading from the misnamed “safe room” to the house’s front door. He worried about how his mother would survive without her inhaler but counted himself lucky that she was alive. “There are a lot of places that have been burned to the ground and you can’t even bury anyone because they’re just teeth,” he said.

Visiting one such house, he explained how the terrorists achieved their end: “They drilled into the gas pipes and then turned them in so the gas goes into the house. People either come out and die, or they just then throw a match in and kill them.” Some of the victims at Nir Oz were Holocaust survivors. “People who survived the Holocaust found themselves facing another one,” Noam Sagi observed.11

The echos of the Shoah are not mere chance. The Hamas murderers are the direct ideological descendants of the Jew-hating Islamic supremacists in Palestine who allied themselves with Hitler during World War II. Hamas itself is a Palestinian offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood. According to University of Maryland historian Jeffery Herf, the Brotherhood’s founder, Hassan al-Banna, had been “an ardent admirer of Hitler since he first read Mein Kampf.”12 During the current war, Israeli troops found an annotated Arabic copy of Mein Kampf along with weapons and explosives in a Hamas base in Gaza.13

In 1941, a failed pro-Nazi coup in Iraq culminated in the farhud (“violent dispossession”), a pogrom not unlike the one organized by Hamas today. Here is how Edwin Black, author of the 2010 book The Farhud: Roots of the Arab-Nazi Alliance in the Holocaust, describes the carnage: “Hundreds of Jews were cut down by sword and rifle, some decapitated. Babies were sliced in half and thrown into the Tigris river. Girls were raped in front of their parents. Parents were mercilessly killed in front of their children. Hundreds of Jewish homes and businesses were looted, then burned.”14

In a sad epilogue to those long-ago events, an elderly Iraqi Jew fell victim to the Hamas massacre at Nir Oz. Sa’id David Moshe, 75, a vegetable farmer, was killed at the kibbutz and his wife Adina, 72, taken captive (she was freed on November 24). Born in Iraq, Moshe moved to Israel as a baby with his family in 1950.15 Between 1950 and 1951, some 120,000 Iraqi Jews emigrated to Israel, fleeing persecution in the land where their ancestors had lived for 2,600 years. Jubilant crowds stoned the trucks carrying the refugees to the airport, mocking the Jews every step of the way.16

Yet Moshe bore no animus against Muslim Arabs. His nephew said that Moshe and his wife “believed in coexistence.” Their daughter Maya Shoshany said Moshe was “a lover of people who believed in peace. He worked with many Bedouins, and when Gaza was still open [before Hamas seized control], he would work with people from there too.”17 Seven decades after his family was driven from Iraq by Muslim Jew-haters, exponents of the same murderous ideology caught up with him in Israel.

Kibbutz Be’eri

Be’eri was one of the worst-hit. More than 130 members of the community were murdered. One of the survivors, Adi Efrat, recounts a surrealistic conversation she had with two terrorists who were tired after a hard day’s work slaughtering Jews. “They told me they had finished what they had done here and they wanted to just go home.” But they needed transportation for the commute back and asked Efrat for her car. She tried to explain that she didn’t own a car. The kibbutz was a socialist community; there were no private cars. “They looked like they didn’t believe me,” Efrat recalls. Then she handed over the immobilizer so that they could get into any of the communal cars. “I told them in Arabic ‘a hundred cars’. They looked excited to know they could have that many.”18

Efrat can communicate in Arabic because her parents immigrated to Israel from Morocco in 1956. They were part of a mass wave of Moroccan Jews fleeing discrimination and persecution. In 1948, a few days after Israel’s declaration of independence, pogroms in the Moroccan cities of Djerada and Oujda had killed dozens of Jews. Four more died at Oujda in 1953. In 1954, mobs sacked the mellahs (ghettos) of Casablanca, Rabat and Petitjean (today Sidi Kacem), burning schools and synagogues.19

Pogroms against Moroccan Jews were nothing new. In 1907, 30 Jews were massacred in Casablanca and, according to a contemporary account, “all the young girls were raped.”20 In 1912, some 60 Jews were murdered in Fez; they were defenseless because the French had confiscated their weapons.21 What changed after 1948 was the existence of a refuge where Jews had the right to fight back. Terrified Jews of the generation of Adi Efrat’s parents now had a place to go. Yet the pogroms never end. “For years we tried to be at peace with them,” Efrat concludes, but it “came back at us like a boomerang. And those people said all the time that they want us dead.”22

Among the murdered at Kibbutz Be’eri was Lilach Havron Kipnis, 60, a social worker who treated children suffering from the trauma of war. Her son Yotam spoke at her funeral about her peace activism: “My mother not only treated the damages of war, she also fought so that future generations would not have to deal with them.” He said that his mother was a member of the antiwar groups Women Wage Peace and Women in Black. Lilach’s husband Eviatar Kipnis, also a peace activist, had been confined to a wheelchair after an accident. Hamas murdered him along with his Filipino caretaker, Paul Vincent Castelvi, who was awaiting the birth of his first child.23

Kipnis’s sister, Dr. Shoshan Haran, 67, was kidnapped from Kibbutz Be’eri. Haran gave up a high-paying job in biotech to found Fair Planet, an NGO that trains African farmers and provides them with seed varieties specially adapted to local conditions. Active in Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Rwanda, Fair Planet says it “has enabled tens of thousands of previously impoverished farmers to earn a good living while providing an estimated million Africans with a reliable source of food.”24

Shoshan Haran’s husband, Avshalom Haran, was murdered on the spot. Their daughter Shaked Haran said her parents had been committed to peace and raised her “to think about the person on the other side of the situation.” After Palestinian workers “couldn’t come anymore because of the security risk,” Shaked recalled, “the kibbutz kept sending them money to help their families.”25 On November 25, Shoshan Haran was freed along with her daughter Adi and Adi’s two children. At this writing, Adi’s husband is still a captive.26

Dr. Hagit Refaeli Mishkin, 48, a school teacher and educator, was murdered near Be’eri. She did not live in the kibbutz but was visiting the area to take part in a planning meeting for Midburn, Israel’s version of the Burning Man festival. Mishkin was the head of the Mofet Institute’s TESFA program, dedicated to integrating students and teachers of Ethiopian origin into the educational system (tesfa means “hope” in Amharic). Her LinkedIn profile credits her with doubling the number of Ethiopian teaching staff in Israel. The Mofet Institute described her as a social activist who “worked tirelessly to create a better, more accepting and tolerant society.”27

Vivian Silver, 74, was one of Israel’s best-known peace activists. After the 2014 Gaza war, she co-founded Women Wage Peace, whose website claims it has 45,000 Israeli members. Before that, Silver had been co-executive director of the Arab-Jewish Center for Empowerment, Equality, and Cooperation (AJEEC) – Negev Institute. AJEEC is a “joint team of Arabs and Jews” that promotes leadership and social involvement among Arab youth, development in the Bedouin community, and the creation of a shared society for Arabs and Jews throughout Israel. The Negev Institute for Strategies of Peace and Economic Development brings community leaders from Africa, Asia and South America to its training center in Beersheba (ajeec-nisped.org.il).

In her spare time, Vivian Silver volunteered to drive Arab patients and their families from Gaza to hospitals in Israel. On October 4, only a few days before the massacre, Silver had marched in Jerusalem with a thousand Jewish and Arab women united for peace under the banner of “The Mother’s Call.” On the morning of October 7, Silver texted her children that she had retreated to a safe room closet after hearing gunfire and shouts outside. Next time, she joked, she would keep a big knife in the closet.28 But there would be no next time. Soon she wrote that the terrorists were in the house: “It’s time to stop joking and say goodbye.” For nearly five weeks, her family thought she had been abducted from Kibbutz Be’eri because her body was not found. Forensic specialists finally identified her remains through DNA analysis after sifting through the ashes.29

Kibbutz Holit

Deborah Martias was killed at Kibbutz Holit shielding her 16-year-old son, who was shot in the abdomen but survived by hiding under his parents’ dead bodies. Deborah’s father, Brandeis Professor Emeritus Ilan Troen, said that she and her husband Shlomi were “idealists” who sent their kids to a school that taught in both Hebrew and Arabic in order to promote better understanding between Jews and Arabs.30

Dr. Hayim Katsman, 32, had returned to Kibbutz Holit after writing a dissertation at the University of Washington on religious Zionist communities. A promising scholar who had won the Association for Israel Studies prize for best graduate paper, Katsman was interested in the relationship between religion and radicalism. “His work helped illuminate some of the very dynamics that have brought us to this horrific moment,” said UW professor Liora Halperin.

Katsman was active with several groups campaigning for peace or the rights of Palestinian Arabs. When terrorists shot through the door of his hiding place, his body absorbed the bullets, saving the woman sheltered behind him, who went on to save two small children. Katsman’s mother recalled that her own mother had fled Hitler’s Germany while her father had survived the Shoah in Poland with false papers. “It’s chilling to me,” she said, “that my son died hiding in a closet.”31

Kibbutz Kfar Aza

Cindy Flash, 67, a retired college administrator, and her husband Igal Flash, 66, a conservation farming instructor, were among the dead at Kfar Aza. “They cared about other people,” their daughter Keren recalled. “They fought for other people’s rights and other people’s voices.”32 Keren Flash said her mother was a lifelong advocate for Palestinian Arabs who had protested Israel’s 2014 war in Gaza. Cindy liked to say, “You don’t solve violence with violence.”33 She will not be protesting the current war in Gaza. On October 7, Hamas carried out the final solution to the existence of Cindy and Igal Flash.

Many other Kfar Aza residents shared their dedication to peace. The kibbutz had a special tradition. Every year, on an early October day when winds were strong, residents would fly “peace kites” along the fence with Gaza as an expression of their good will. This year, the kite festival fell on October 7. Relatives of kibbutz members had arrived the night before. The next morning, Hamas terrorists came with weapons of war and methodically murdered at least 60 unarmed individuals. The body of Aviv Kutz, 54, the founder of the peace kite festival, was found in his bed with his arms around his wife and three children––all dead.34

Other families were bound and tortured before being killed.35 Jamal Warraqi, a Muslim Israeli Arab, was among the first emergency responders. “I saw families, they were slaughtered, a lot of families,” he remembered, still visibly shaken. “I saw a father and mom with three kids, they were tied hands up, hands back… as they were put on their knees in front of each other, then they got shot in the head.”36

For two years before the attack, Hamas had refrained from any new military operations while feigning a newfound interest in the economic well-being of Gaza’s population.37 “We all really believed that things are changing,” said Kfar Aza resident Hanan Dann. “That Hamas has maybe matured from being this terrorist group to being the grown up; taking responsibility for their people, worrying for their welfare. And that concept really blew up in our face.”38

A purifying sacrifice?

The violence of the massacres committed by Hamas is so extreme as to defy easy analysis. An example from a context that has nothing to do with the Arab-Israeli conflict may help us gain perspective. During the Algerian civil war of the 1990s, Islamic extremists carried out comparable massacres of civilians, in some cases wiping out whole villages. Anthropologist Abderrahmane Moussaoui suggests that those acts of violence could in certain respects be understood as “sacrificial rituals.”39

A massacre committed in wartime is not the same thing as a religious sacrifice in the strict sense. But René Girard’s anthropological theory offers “an expanded concept of sacrifice in which the sacrificial act in the narrow sense plays only a minor part.”40 For Girard, many different forms of violence, from impromptu lynchings to solemn rites performed at sacrificial altars, are ultimately rooted in the same scapegoat mechanism. Between “spontaneous outbursts of violence” and formal religious rituals, Girard writes, “innumerable intermediate stages exist.”41

Girard’s theoretical approach does not invalidate other ways of understanding any given instance of violence, but it often makes visible aspects that would otherwise go unnoticed. Let us ask, therefore, whether the massacres perpetrated by Hamas are sacrificial in Girard’s sense. Abderrahmane Moussaoui affirms that the violence of the massacres committed by Algerian extremists was sacrificial insofar as it aimed at “protecting the majority of the population by ‘purifying’ it of a minority (sacrificial victim) deemed dangerous.” Citing René Girard and others, Moussaoui adds that the “the main goal of all sacrifice” is to improve well-being and “reestablish an order and harmony.”42

If we wish to apply this definition to the recent massacres of Israeli civilians, we need to ask what form of order or harmony the violence aims to reestablish. Is there some time-honored way of organizing society that in the eyes of Hamas has been lost and needs restoring? The Islamist group’s avowed goal is not simply to end the occupation of disputed territories; it is to eliminate Israel entirely. Accomplishing that goal, even if it stopped short of killing all the Jews living there, would, at a minimum, strip them of the right to govern themselves in a free and independent state. We must therefore ask what traditional order is threatened by the very existence of Jewish self-rule in a relatively small corner of the Muslim world.

Once the question is formulated in this way, the answer becomes clear: the existence of Israel subverts the traditional order regulating the place of Jews in Muslim society. As People of the Book, Jews (and Christians) were tolerated on condition that they pay an onerous tax, wear distinctive garb, show deference to Muslims, and submit to a series of humiliating restrictions. In a culture where men rode camels or horses and wore swords, Jews were not allowed to mount on saddles or carry weapons. This last prohibition made Jews vulnerable to physical attack.

The status of Jews was contradictory and precarious; they were integrated into society as perpetual outsiders. “Marginal but not excluded,” as Mark Cohen puts it, Jews could “participate in a wide range of activities” alongside Muslims so long as they never forgot their “lowly rank” and remained “in their place.”43 At once marginal and defenseless, the Jews constituted a permanent reserve of potential victims. “The victim should belong both to the inside and the outside of the community,” René Girard writes. In Girard’s terminology, the Jews were eminently “sacrificeable.”44

Outbreaks of persecution were often motivated by the perception that Jews were getting uppity. In Muslim Granada, a Jew rose to the lofty position of vizier, but his son and successor was assassinated in 1066, and “a mob massacred the entire Jewish community.” According to a contemporary witness, “Both the common people and the nobles were disgusted by the cunning of the Jews, the notorious changes which they had brought about in the order of things.”45

For Islamic supremacists today, the existence in Palestine of uppity Jews who refuse to submit to Muslim rule is a cataclysmic change that threatens the age-old order of things. As Cohen notes, “the presence of Jews and Christians in a marginal situation within the hierarchy of Islam constitutes a structural feature of its social order.”46 When a society’s religious framework “starts to totter,” Girard remarks, “the whole cultural structure seems on the verge of collapse.”47

To Hamas, Zionists are dangerous rebels against the traditional order. In Abderrahmane Moussaoui’s formulation quoted above, sacrificial violence serves to “purify” the population of a “minority (sacrificial victim) deemed dangerous.” The name that Hamas gave the attack underscores the purificatory, cleansing mission assigned to it: “Operation Al Aqsa Flood.”

Unlike Sunni Muslims, Shiites consider Jews and Christians to be carriers of ritual impurity.48 Although Palestinian Arabs are overwhelmingly Sunni, Hamas is sponsored by Iran, the leading Shiite power, and is allied with Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shiite militia. The explanatory framework proposed here makes it possible to understand why Iran and its proxies should be the most virulent holdouts against recognition of a Jewish state. Shiism, Cohen observes, “was usually harsher in its view of how the infidel should be treated.”49 Bernard Lewis describes how Iran was historically less tolerant of Jews and enforced customary restrictions against them much more rigorously than its Sunni neighbors.50

A number of Sunni Arab governments have overcome the archaic outlook exemplified by Hamas and recognize the legitimacy of a Jewish state. This was demonstrated most recently by Israel’s signing of the Abraham Accords with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, followed by normalization agreements with Morocco and Sudan. Many observers believe that the Hamas attack was designed in part to derail negotiations for a new agreement with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s greatest regional rival.

It would therefore be a mistake to interpret the current explosion of violence as an “escalation to extremes” of the broader Arab-Israeli conflict. On the contrary, it is a reaction against the great strides being made toward peaceful coexistence in the region. These developments spell the failure of Hamas’s hardline rejectionist strategy and represent a crisis for the organization. The extreme nature of the violence to which Hamas resorted indicates the gravity of the perceived threat and may be understood in Girardian terms as an attempt to effect a sacrifice powerful enough to resolve the crisis.

One overlooked aspect of the Hamas attack tends to confirm its sacrificial character: the collective participation on the part of Gaza’s population. Such participation is essential to the achievement of what Girard calls violent unanimity. He provides examples where the “sacrificial ceremony requires a show of collective participation, if only in purely symbolic form.”51 In the case of the Hamas attack, a dozen survivors of the Nir Oz massacre told a journalist that gunmen entered the kibbutzes accompanied by civilians, including women and children, who took part in the looting. One survivor said that ordinary men, women and children far outnumbered the armed terrorists.52

The participation of a cross-section of the Gazan population helped insure that the entire community would embrace the violence. Sacrifice and the killing of enemies are mechanisms for generating consensus.53 At least in the short term, Hamas succeeded in uniting its own constituency around the massacre. On the eve of the attack, an Arab Barometer survey revealed that two-thirds of Gazans had little or no trust in Hamas. They blamed the Gaza Strip’s poverty more on Hamas corruption than on Israel.54

But a survey conducted afterwards by the Ramallah-based Arab World for Research and Development firm found that Hamas has reversed the decline in its popularity. Three out of four West Bank Arabs and residents of southern Gaza now have a positive view of Hamas and support its actions on October 7. Fully 98% said the attack made them feel “prouder of their identity as Palestinians.”55 On this point, there was virtual unanimity.

However, the consensus in favor of the Hamas attack did not extend to the Arab citizens of Israel. A poll conducted by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Agam Institute produced diametrically opposite results. More than three out of four Israeli Arabs opposed the Hamas attack and 85% denounced the taking of civilian hostages. The Arab parties present in the Israeli parliament were unanimous in condemning the attack.56 That is a failure for Hamas. It suggests that the violence backfired by reinforcing the unity of the Israeli population.

Epilogue: Moshav Motza

In 1929, the Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini, who would go on to collaborate with the Third Reich, instigated bloody massacres of Jews in localities across Palestine.57 This is not the place for a history of those events. A single little-known example, that of Motza, will suffice for our purposes.

We began with the Hamas attack on the Netiv HaAsarah moshav (agricultural settlement). Motza, a small village built outside Jerusalem in the mid-19th century, was the first moshav in modern Israel. Before the pogroms of 1929, the residents enjoyed good relations with their neighbors. One Jewish woman, Haya Machlef, was a nurse who tended to the local Arabs. In August 1929, a shepherd employed by the Machlef family led a mob to their home. The Arabs raped and killed two daughters and murdered the father and two houseguests. Haya, the nurse, was tortured and left to die.58

Four decades later, after the 1967 war, an Israeli intelligence officer found a secret operational order concerning Motza in captured Jordanian army files. “The inhabitants number about 800 persons, engage in agriculture and have guard details in the colony,” the order noted. “The intention of H.Q. Western Front is to carry out a raid on MOTZA Colony, to destroy it and to kill all its inhabitants.” One company was to do the killing while another blocked rescue operations. When Jordan attacked in 1967, Motza came under heavy shelling, but the units assigned to exterminate the residents were repelled.59

After the war, journalist Howard Singer visited Motza and interviewed two typical residents. Gavriel was born in Jerusalem; his family on his mother’s side had lived there for 500 years. His wife, Alisa, of German Jewish background, was born in Tel Aviv. They lived in a two-story fieldstone house that Gavriel had built with his own hands. Singer asked Alisa whether she had any special reaction upon learning that Arabs from across the border had been planning to kill her. “No, I’m quite sure I didn’t,” she said. “After all they had been telling us that all along.”

“But this is different,” Singer insisted. “A broadcast may be propaganda, but an operational order is a loaded gun pointed at the target. At you.” Gavriel shrugged. “I don’t know why it should come as a surprise to you,” he said. “Civilians? By now we know the rules don’t apply to us. Alisa’s parents got out of Europe in time, but her grandparents did not. They were civilians too, you know. I think the beginning of wisdom is to accept that, you see; the guns will always be pointed at us.”

“No reaction at all then?” Singer asked. Gavriel hesitated before replying. “The only reaction I had—and I think this was true of everyone around here—was, I suppose, a kind of pity. For them, not us.”60

1. Adele Raemer, “Here’s How Women Wage Peace,” Times of Israel, Oct. 19, 2016; PathtoPeaceWall.com.↩

2.Deena Yellin, “NJ man recalls terror of Hamas attack at music festival: ‘They kept shooting and shooting’,” NorthJersey.com, Nov. 10, 2023.↩

3. Liel Leibovitz, “Eyewitness Account of the Rave Massacre,” TabletMag.com, Oct. 8, 2023.↩

4. Yellin, “NJ man recalls terror.”↩

5.“Four Bedouin drove from Rahat to evacuate their cousin in Be’eri; they rescued dozens,” Times of Israel, Nov. 5, 2023.↩

6. Yellin, “NJ man recalls terror.”↩

7. John Jeffay, “Survivors of Kibbutz Nir Oz massacre speak out,” Israel21c.org, Nov. 16, 2023.↩

8. Sarah Fowler, “I went through hell, says elderly hostage released by Hamas,” BBC News, Oct. 24, 2023.↩

9. “Portraits of those held hostage by Hamas after attack on Israel,” APNews, Nov. 9, 2023; Emine Sinmaz, “‘This was her heaven’: son returns to Israel kibbutz where his mother was abducted,” The Guardian, Nov. 13, 2023.↩

10. Danica Kirka and Ami Bentov, “Families in Israel and abroad wait in agony for word of their loved ones,” APNews, updated Oct. 12, 2023; David Rose, “Lifelong peace activist among those kidnapped by Hamas in wave of terror,” Jewish Chronicle, Oct. 12, 2023; Emine Sinmaz, “‘They had no chance’: UK relatives of missing Israelis pray for their release,” The Guardian, Oct. 14, 2023.↩

11. Rose, “Lifelong peace activist among those kidnapped”; Sinmaz, “‘This was her heaven’: son returns to Israel kibbutz.”↩

12. Jeffrey Herf, “Nazi Antisemitism & Islamist Hate,” TabletMag.com, July 6, 2022. Herf cites a number of recent scholarly works, including Matthias Küntzel, Jihad and Jew-Hatred: Islamism, Nazism and the Roots of 9/11 (Telos, 2013) and David Motadel, Islam and Nazi Germany’s War (Harvard, 2014).↩

13. Itamar Eichner, “Herzog: ‘Mein Kampf’ found at Hamas stronghold,” Ynetnews, Nov. 12, 2023.↩

14. Edwin Black, “The expulsion that backfired: When Iraq kicked out its Jews,” Times of Israel, May 31, 2016.↩

15. “Sa’id David Moshe, 75: Yom Kippur War veteran and dedicated farmer,” Times of Israel, Oct. 23, 2023.↩

16. “The expulsion that backfired.”↩

17. “Sa’id David Moshe, 75.”↩

18. Michelle Rosenberg, “‘I was captured by Hamas. They killed 120 on my kibbutz. Somehow I survived’: What Adi Efrat saw and heard at Be’eri,” Jewish News, Nov. 12, 2023.↩

19. Moïse Rahmani, Réfugiés juifs des pays arabes: L’exode oublié (Editions Luc Pire, 2006), p. 131.↩

20. Eunice G. Pollack, Ph.D., “The Oct. 7 massacre and its apologists in historical perspective,” JNS.org, Nov. 9, 2023.↩

21. Rahmani, Réfugiés juifs des pays arabes, pp. 130-31.↩

22. Rosenberg, “I was captured by Hamas.”↩

23. “Lilach Kipnis, 60: Child trauma specialist and peace activist,” Times of Israel, Nov. 10, 2023; “Eviatar ‘Tari’ Kipnis, 65: A skipper and peace activist,” Times of Israel, Oct. 18, 2023; “Paul Vincent Castelvi, 42: Filipino carer’s first child born posthumously,” Times of Israel, Nov. 14, 2023.↩

24. Bernard Dichek, “Shoshan Haran, presumed captive, has dedicated her life to helping African farmers,” Times of Israel, Oct. 19, 2023; FairPlanet.ngo.↩

25. “Portraits of those held hostage”; Irin Carmon, “‘It’s Really Hard to Hold On in This Reality’: Ten members of Shaked Haran’s family are believed to be hostages of Hamas,” New York Magazine, Oct. 17, 2023.↩

26. “Yahel Shoham, 3, and 5 members of her wider family freed; her dad still held in Gaza,” Times of Israel, updated Nov. 25, 2023.↩

27. “Hagit Refaeli Mishkin, 48: Educator, activist & ‘Midburn’ organizer,” Times of Israel, Oct. 29, 2023.↩

28. Sam Lin-Sommer, “Vivian Silver, 74-year-old peace activist, grandmother, and friend, confirmed dead,” Forward, updated Nov. 13.↩

29. Jenni Frazer, “Israeli peace activist believed to be held hostage is confirmed dead,” Jewish News, Nov. 14, 2023.↩

30. “What we know about the Americans missing or killed in Israel,” New York Times, Oct. 12, 2023.↩

31. Beth Harpaz, “He was a peace activist with a PhD. In dying, Hayim Katsman saved 3 other lives,” Forward, Oct. 12, 2023.↩

32. “Cindy and Igal Flash, 67 & 66: ‘They were my inspiration’,” Times of Israel, Oct. 20, 2023.↩

33. Kim Hjelmgaard, “An American mom, 67, spent her life advocating for Palestinian rights. Then Hamas came,” USA Today, updated Oct. 12, 2023; “Who were the Americans killed in Israel? What we know so far,” Washington Post, Oct. 11, 2023.↩

34. Susan Ormiston, “‘They’ve got me’: Father of Israeli woman taken hostage relives daughter’s words as hope for peace fades,” CBC News, Nov. 11, 2023; “Kutz family: Father, mother and three teens die in embrace,” Times of Israel, Oct. 14, 2023.↩

35. Stuart Ramsay, “Israel-Hamas war: Recovered bodies show ‘bloodthirsty’ gunmen ‘took time over torture’,” Sky News, Oct. 16, 2023.↩

36. Eli Berlzon, “Muslim rescuer says Israel kibbutz bloodshed caused by attackers’ hate,” Reuters, Nov. 17, 2023.↩

37. Samia Nakhoul and Jonathan Saul, “How Hamas duped Israel as it planned devastating attack,” Reuters, Oct. 10, 2023.↩

38. Deborah Danan, “1 month after Oct. 7 massacre, the ruins of Kibbutz Kfar Aza testify to its horrors,” JTA.org, Nov. 7, 2023.↩

39. Abderrahmane Moussaoui, De la violence en Algérie: Les lois du chaos (Actes Sud, 2006), p. 54.↩

40. René Girard, Violence and the Sacred (Johns Hopkins, 1977), p. 297.↩

41. Girard, Violence and the Sacred, p. 309.↩

42. Moussaoui, De la violence en Algérie, p. 55.↩

43. Mark R. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages (Princeton, 1994), pp. 112-13.↩

44. Girard, Violence and the Sacred, p. 272.↩

45. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross, p. 164-65.↩

46. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross, p. 113.↩

47. Girard, Violence and the Sacred, p. 49.↩

48. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross, p. 64.↩

49. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross, p. xxi.↩

50. See the first chapter of Bernard Lewis, The Jews of Islam (Princeton, 1984).↩

51. Girard, Violence and the Sacred, p. 100.↩

52. Andrew Tobin, “Children as young as 10 took part in Hamas’s Oct. 7 terror attack, survivors say,” World Israel News, Nov. 17, 2023.↩

53. See Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster: Dualism, Centralism and the Scapegoat King in Southeastern Sudan, 2nd ed. (Fountain, 2017).↩

54. Nicolas Revise, “Rare Survey Details How Gazans Wary of Hamas Before Israel Attack,” Barrons, Nov. 27, 2023.↩

55. Akiva van Koningsveld, “Three in four Palestinians support Hamas’s massacre,” JNS.org, Nov. 17, 2023.↩

56. Théophile Simon, “Le dilemme des Arabes israéliens,” Le Point, Nov. 2, 2023, p. 64.↩

57. On al-Husseini’s collaboration with Hitler, see Herf, “Nazi Antisemitism & Islamist Hate.”↩

58. Aviva and Shmuel Bar-Am, “Motza, first agricultural colony in modern Israel,” Times of Israel, July 20, 2013.↩

59. Howard Singer, Bring Forth the Mighty Men: On Violence and the Jewish Character (Funk & Wagnalls, 1969), pp. 179-80; the original operational order in Arabic is reproduced in the book’s appendix with a facing translation.↩

60. Singer, Bring Forth the Mighty Men, pp. 181-82, 185-86.↩

Event Reports

Be Not Conformed

Curtis Gruenler

It has been remarkable to watch how Luke Burgis, author of Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life, has connected new audiences to mimetic theory. He has appeared on innumerable podcasts and videos, including a “COV&R Convo” with Matt Packer. He has published articles in a number of publications aimed at a broad readership. Anti-Mimetic, his publication on Substack, boasts over 21,000 subscribers and has also been a platform for organizing online events. “Be Not Conformed,” the November 3 conference he organized at The Catholic University of America in honor of the centenary of René Girard’s birth, was a culmination of this work so far. It brought together speakers and participants from a variety of backgrounds, professional and otherwise, most of whom seemed relatively new to Girard. Only a handful of the 57 speakers listed in the program would be familiar from their appearance at COV&R conferences.

It has been remarkable to watch how Luke Burgis, author of Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life, has connected new audiences to mimetic theory. He has appeared on innumerable podcasts and videos, including a “COV&R Convo” with Matt Packer. He has published articles in a number of publications aimed at a broad readership. Anti-Mimetic, his publication on Substack, boasts over 21,000 subscribers and has also been a platform for organizing online events. “Be Not Conformed,” the November 3 conference he organized at The Catholic University of America in honor of the centenary of René Girard’s birth, was a culmination of this work so far. It brought together speakers and participants from a variety of backgrounds, professional and otherwise, most of whom seemed relatively new to Girard. Only a handful of the 57 speakers listed in the program would be familiar from their appearance at COV&R conferences.

The day’s wide-ranging conversation began with a plenary panel featuring three African-American writers and commentators: Thomas Chatterton Williams, who has written about Girard, Coleman Hughes, and Lester Spence. A discussion of how to respond to the current “moment of Black cultural dominance” elicited a very Girardian question from moderator Hollis Robbins, how to avoid joining a mob. Spence answered with a story about Martin Luther King, Jr., saying to Harry Belafonte that he feared that his people were integrating into a burning house. Belafonte asked, “What should we do?” and King replied, “Become the firemen.” One thing this means, Spence added, is broading the perspective, “but respectability always narrows.” Williams pointed to novelist Ralph Ellison’s insights about being black as a discipline, as figured by “the jazz man” encountering situations with improvisation.

The other two plenary panels followed further directions that Burgis’s book has opened up. One, featuring Craig Robins, the developer of the Miami Design District, Alexandra Winokur, president of Christian Dior Couture Americas, and Ryan Resch, vice president of basketball strategy for the Phoenix Suns, addressed how to maintain creative community in settings where awareness of desire and rivalry is especially salient. (This window into the operations of a professional sports team made me think of the Apple TV series Ted Lasso, which strikes me as full of lessons in positive management of mimetic desire.) A panel on new media got a bit sidetracked, despite the best efforts of moderator Ross Douthat, on assigning blame for its problems. I had been hoping to hear more from Hamish McKenzie, co-founder of Substack, about his rationale for an alternative.

Keynote speaker Peter Thiel delivered another version of the address he gave at last summer’s COV&R meeting, “Nihilism Is Not Enough.” Asked in the discussion period whether repentance would be enough, he referred to an oft-cited remark by Girard that we might start by going to church. His call for an ambitious response to the crises of our time concluded with the splendidly ambiguous and provocative sentiment that we need more of the religion of Constantine rather than that of Mother Theresa.

The parallel sessions offered a similarly venturesome array. Readers may remember my thoughts about Girardian notes in Bob Dylan’s most recent album, but Jeff Takacs laid out a tour-de-force comparison of the “twin odysseys” that began almost simultaneously with Girard’s first book and Dylan’s first album. The parallels are astonishing. “Beyond Deceit: René Girard and Luigi Giussani on the Meaning of Desire,” introduced me to a thinker whose work, according to panelists Maria Elena Monzani, Tyler Graham, and Thomas Deutsch, would seem to take an opposite view of desire from Girard’s but, on closer inspection, can enter into a fruitful dialogue with it (one that might extend the similar relation I have explored between Girard and C. S. Lewis). Attendees could get an idea of the parallel sessions they missed courtesy of 227-page book containing drafts of most of the papers.

The conference proper closed with remarks of moving and understated eloquence by Girard’s eldest son, Martin. Thanking the audience for their interest in his father’s ideas, “or what he’d rather call discoveries,” Martin added, “He considered himself a researcher seeking understanding and truth, not an ideologue constructing a fixed, closed system… Now there are labels for it—mimetic theory, the scapegoat mechanism—that make the work seem complete. But the work was never done.” After a particularly vigorous debate, Martin recalled, what his father had to say was, “He might be right.” His father’s advice was to choose good models. He had more to offer about how to live than to go to church. He lived, Martin said, by a code of values, among them humility, forgiveness, treating people with respect, looking out for the vulnerable, peace.

An evening banquet featured an address by Dom Elias Carr, an Augustinian canon and Catholic school administrator whose beginner’s guide to mimetic theory will be published by Word on Fire in 2024. The highlight for me, however, was to see the innaugural Novitāte award for an extraordinary contribution to the conference’s theme go to Cynthia Haven, author of Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard and editor of All Desire Is a Desire for Being: Essential Writings of René Girard as well as her blog, The Book Haven.

Novitāte: New Models of Thought and Desire is to be an annual conference of which this was the first. It’s not clear how much Girard’s work will continue to be the inspiration for later installments, but the name suggests a Girardian diagnosis of how being stuck in old models calls forth a need for something new.

One final note: the conference actually began on the evening of November 2 with a preview screening of “Things Hidden: The Life and Legacy of René Girard,” a full-length documentary directed by Sam Sorich. I was not able to attend, but it was getting a lot of good buzz the next day. A significant amount of post-production work remains to be done, and permissions to be obtained, before it is ready for release, but this will be an event to look forward to.

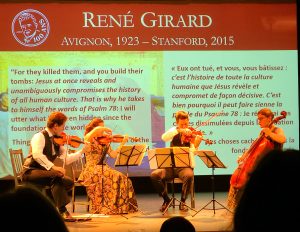

René Girard 100 Year Memorial Concert

Martha Reineke

On behalf of COV&R, I accepted an invitation from the French consulate in San Francisco to attend a reception and memorial concert in honor of René Girard at the Lycée Francais de San Francisco. The event, which featured the Quatuor Girard, took place on September 13, 2023, and included works by Bach, Lekeu, and Mendelssohn. The Quatuor Girard is a string quartet from Avignon, France, comprised of grandnieces and nephews of René Girard. Quotations from Girard’s writings were projected on a screen behind the performers, and grandson Matthew Girard read from his grandfather’s publications. Eldest son Martin Girard offered remarks. Family members from the U.S. and France as well as friends from the Bay Area were well represented at the event. I was able to pay my respects on behalf of COV&R to Martha Girard, René’s wife and a regular attendee at COV&R meetings over many years.

I am deeply appreciative of the French consulate for their recognition of René Girard. Heartfelt sentiments about his life and legacy shared during the evening will be long remembered by everyone who attended.

Commentary

What George Bailey Gave and What George Pratt Received

Andrew McRae

The film It’s a Wonderful Life shows audiences a single person, George Bailey, whose breadth of impact can only be fully appreciated by stepping back to view the town of Bedford Falls as a whole. The character himself cannot take in the full scope of his own life’s work until a guardian angel grants him his wish to have never been born. Then, with merely his corporal presence intact, he investigates his hometown as a stranger and is swiftly bowled over at how drastically people and things have changed.

After the unsettling visit, George Bailey races frantically back to the bridge where he had had his wish granted. He is driven by newfound knowledge of what-would-be-if-he-were-not and by penetrating clarity on all-that-is-because-he-was.

After the unsettling visit, George Bailey races frantically back to the bridge where he had had his wish granted. He is driven by newfound knowledge of what-would-be-if-he-were-not and by penetrating clarity on all-that-is-because-he-was.

Of course, he still faces both the ignominy of being a failed businessman and the high likelihood of going to jail, but these are manageable burdens he will gladly endure. There is simply too much on the other side of the exchange: a great number of lives that stand to be saved (his brother’s along with all the soldiers on two WWII transport ships), a smaller number of lives that will be greatly improved (like Martini the barkeep and Gower the pharmacist), and the four lives in whose very creation he participated as father. With so much to gain, what price wouldn’t a man like George Bailey pay?

Arriving at the bridge, the pleas to his guardian angel take a chiastic structure centered on self-disregard.

(a) Clarence! Clarence! Help me, Clarence!

(b) Get me back! Get me back!

(c) I don’t care what happens to me.

(b’) Get me back to my wife and kids.

(a’) Help me, Clarence, please…

“Please, I want to live again! I want to live again.”

The immense impact of George Bailey’s life extends beyond its effects on other individuals; it also reaches into the realms of societal formations (e.g., the pervading character of the main street business district, the general disposition of locals toward strangers in the bar outside of town). So, George Bailey is not just one being affecting other beings of the same sort; he’s also being of a lower modest order who somehow brings higher order overarching realities into existence.

It’s as if this single man is the lynch pin that holds the whole wholesome town together. So, it is not without coherent reasoning that such a man might willingly yoke the logic of Caiaphas to his own neck.

The Greatest Gift, the 1943 short story upon which the 1946 film is largely based, starts thematically in the same place: a Christmas Eve wish on bridge to have never been born. However, the written work ends somewhere both so similar and so different it makes sense to see its screen adaptation as an inversion. The film discloses myriad threads of influence branching outward from a single individual; and while the short story depicts a similar bundle of threads, they grow out of the community and converge on one spot to create a single person.

Unlike the movie, brother Harry was never a war hero, there are no counterparts to Martini and Gower, and Mary doesn’t need a George to marry and have children. More importantly, George Pratt (not Bailey) is not facing any professional catastrophe or jail time. The short story simply presents its protagonist as an average ordinary who has had enough ordinary.

“I’m stuck here in this mudhole for life, doing the same dull work day after day. Other men are leading exciting lives, but I—well, I’m just a small-town bank clerk that even the Army didn’t want. I never did anything really useful and interesting, and it looks as if I never will. I might just as well be dead. I might better be dead. Sometimes I wish I were. In fact, I wish I’d never been born!”

Pratt also makes a visit through a hometown that is now what has never been his home. When he races hurriedly back to the bridge, he too possesses more knowledge than before and is quite confident in a new perspective illumined by what would have been. However, unlike Bailey, Pratt is not making a wretched utilitarian calculation in which he sacrifices his own standing for the betterment of everyone else. He is basking in the glow of a purely felicitous utilitarian calculation in which everyone without exception stands to come out ahead.