In this issue: reports from COV&R’s annual meeting, four book reviews, many forthcoming events, new publications, and a new Girard society.

Contents

Editor’s Column: Curtis Gruenler, Reviews and News

Justice, Joy, and Storytelling with Iain Coston, Online, August 30, 2023

René Girard 100 Year Memorial Concert, San Francisco, September 13, 2023

James Alison Workshop, Melbourne, September 23, 2023

Public Forum with James Alison, Syndey, October 5, 2023

Theology & Peace Annual Gathering, Chicago, IL, October 5-8, 2023

Be Not Conformed: René Girard at 100, Washington, DC, November 3, 2023

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion, San Antonio, TX, November 18-21, 2023

René Girard Centenary, Paris / Avignon, December 14-17, 2023

COV&R Annual Meeting, Mexico City, Mexico, June 26-29, 2024

Event Report: Curtis Gruenler, Reflections on COV&R’s Annual Meeting, 2023

Letter from…Avignon: Mark R. Anspach, New Girard Society Founded

Mark R. Anspach, The Empire of Value: A New Foundation for Economics, by André Orléan

Musings from the Executive Secretary

Notes from the COV&R Business Meeting in Paris

Nikolaus Wandinger

At the end of the Paris conference fully packed with interesting presentations in plenary and concurrent session, quite a few members still had the energy to attend the Business Meeting of the Colloquium.

There were the usual reports about our finances (doing okay), our publications (still going strong), and our activities at the AAR, of which you will find a preview in this Bulletin.

What attendees were probably most interested in was Tania Checchi’s preview of the plans for next year’s conference in Mexico City. We were almost awed at the advanced stage of the planning and the thoughtful choosing of the theme (Desire among the Ruins: Mimesis and the Crisis of Representation) and of the location, and we almost wished that the conference dates (June 26 to 29, 2024) were already here. You can find Tania’s presentation as a little video on the COV&R YouTube Channel, which allows me to keep writing about it brief.

The final, very important item on the agenda was electing—or in this case re-electing—COV&R officers and board members. The following officers’ terms ended: Executive Secretary Nikolaus Wandinger finished his first three-year term and was eligible for a second term; Bulletin editor Curtis Gruenler finished his second term and was eligible for another term as our by-laws impose no term limits on the editors’ posts. Grant Kaplan also finished his term as our coordinator for the AAR; he did not wish to be renewed and suggested as his successor Chelsea King, who has already worked on his team in the past years. Erik Buys and Stephen McKenna each completed their first term as elected board members and were eligible for a second term.

President Martha Reineke thanked Grant Kaplan for his excellent work at the AAR and the members gathered approved through their applause to Grant in absentia. Maura Junius moved that all mentioned persons be re-elected respectively to the suggested positions, Tania Checchi seconded, and the slate was elected unanimously. Next year, quite a number of officers and board members need successors, as many reach the end of their second term and are not eligible anymore—above all President Reineke. So, thoughts for good persons on that Board are welcome. If you have any, send them to me or to President Reineke.

Meanwhile, ideas about the location and hosts of the 2025 conference were ventured but no clear front-runner emerged at the Business Meeting. The Board will meet online in September; maybe more will be known by then.

Editor’s Column

Reviews and News

Curtis Gruenler

Since there is plenty of writing from me elsewhere in this issue, I will keep my comments here short and get to the news. It was great to see many of you in Paris. I appreciate those who mentioned that they would be interested in helping with book reviews. If you would be interested in writing a review or in helping with the process of finding reviewers and editing reviews, please let me know.

Be sure to check out this issue’s reviews and consider sending them to those you know who might be interested. I’ll be sending Mark Anspach’s review of André Orléan’s rethinking of economics through mimetic theory, The Empire of Value, to my economist colleagues—this important book seems to have been overlooked by economics journals in the English-speaking world. My review of Cynthia Haven’s new, career-spanning collection of pieces by René Girard, All Desire Is a Desire for Being, includes her invitation to send more “maxims” like those that make up the final section; you can email your favorites to her here.

Our list of forthcoming events is longer than ever—maybe it includes some to tell friends about.

A 20% discount is available to COV&R members for the six most recent volumes in Michigan State University Press’s Studies in Violence, Mimesis & Culture and Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory, up through Scott Cowdell’s just released Mimetic Theory and Its Shadow: Girard, Milbank, and Ontological Violence. The others are: Alterity by Jean-Michel Oughourlian, translated by Andrew McKenna, Violence and the Oedipal Unconscious, volume 1: The Catharsis Hypothesis by Nidesh Lawtoo, The Time Has Grown Short: René Girard, or the Last Law by Benoît Chantre, Toward an Islamic Theology of Nonviolence: In Dialogue with René Girard by Adnane Mokrani, and Jean-Pierre Dupuy’s How to Think about Catastrophe: Toward a Theory of Enlightened Doomsaying. In addition, a 30% discount is available on selected titles from the backlist with a purchase of three or more. For more information, please see this page in the members section of the COV&R website. The same page includes a discount code for ordering through Eurospan, which has better shipping rates when ordering from Europe than ordering directly through MSUP. Due out later this year from MSUP is Violence and the Mimetic Unconscious, volume 2: The Affective Hypothesis by Nidesh Lawtoo.

A volume of articles based on the proceedings of the 2019 COV&R annual meeting in Innsbruck, Imagining the Other: Mimetic Theory, Migration, Exclusionary Politics, and the Ambiguous Other, edited by Dietmar Regensburger and Nikolaus Wandinger, is now available from Innsbruck University Press, both in print and online. I welcome inquiries from anyone interested in reviewing it for the Bulletin.

Paul Gifford’s 19,000-word article “René Girard and Mimetic Theory” was recently published on the open-access, web-based St Andrews Encyclopaedia of Theology. Its thorough discussion is supported by up-to-date references to Girard’s own works, further theological developments of his thought by others (including many COV&R members), and critiques. Along similar lines, the journal Modern Theology has made available a pre-publication, web version of “Method in Mimetic Theory: René Girard and Christian Theology” by Anthony J. Scordino from the Department of Theology at the University of Notre Dame.

Also noteworthy is Luke Burgis’s article, “Culture War as Imitation Game: The Timeliness of René Girard’s Case against Idolizing Politics,” a substantial article applying mimetic theory for a broad audience in the Summer 2023 issue of The New Atlantis.

The seminar organized annually by the research group in mimetic theory based at the University Francisco de Vitoria, Violencia y Sociedad, will celebrate the centenary of the birth of René Girard with a program entitled “Volver a Girard” on November 17. “The aim,” writes organizer David Garcia-Ramos Gallego, “will be to explore new victims and new radicalization processes from Girard’s original insights, going back to Girard’s texts to explore and map new territories of violence and victimization.” For more information, contact David or Blanca Millán. Submissions are also still being accepted for an issue of Revista Interdisciplinar De Teoría Mimética. Xiphias Gladius on the theme “New radicalities, new victims: Approaching the current phenomena of radicalization” as well as any other proposal concerning mimetic theory. See the call for papers.

Julie and Tom Shinnick are hosting a new read-aloud-and-discuss Zoom group on Cynthia Haven’s Evolution of Desire: A Life of Rene Girard, weekly on Monday nights at 6:30-8:00 Central time. It began August 7, but new participants are welcome any time. Julie writes: “This might be a good introduction to Girard for newcomers, since Haven not only deals with Girard’s life, but also offers commentary on his works. People can drop in and drop out, since there is not really a problem of keeping up. We only read 10-14 pages a week, since we often have interesting discussions along the way. If someone has to miss a couple of weeks, it is easy to catch up, since we make rather slow progress (10-14 pages per week). I send an email each week that tells where we left off, so if someone has to miss a meeting, they can easily catch up with the reading.” Previous Zoom groups have read Mark Heim’s Saved from Sacrifice: A Theology of the Cross and Gil Bailie’s book, Violence Unveiled: Humanity at the Crossroads, and each has concluded with a meeting attended by the author. Please email Julie if you are interested.

The video tributes to René Girard introduced in our previous issue, interviews with 27 of his students, colleagues, and friends conducted by John Babak Ebrahimian, are now available as a playlist on the COV&R YouTube channel. They go back to Girard’s early career teaching at Johns Hopkins University and feature many prominent COV&R members.

Forthcoming Events

Justice, Joy, and Storytelling with Iain Coston

unRival Spaces

Online

Wednesday, August 30, 2023, 8-9pm EDT

Conversation and Q&A with Iain Coston, a peacebuilder and writer living and working in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City. Sign up for free here.

René Girard 100-Year Memorial Concert

San Francisco

September 13, 2023

The French consulate in San Francisco and the Girard family plan a René Girard memorial concert by the Quatuor Girard at the Lycée Francais de San Francisco, 1201 Ortega Street, at 7:00 pm on Wednesday, September 13, 2023. The concert will be open to the public and feature works by Bach, Lekeu and Mendelssohn. Free tickets can be reserved here.

The Quatuor Girard is a string quartet from Avignon made up of grandnieces and nephews of René Girard. They were very much appreciated by René in his later life and played at his memorial mass at the Eglise de St Germain de Près in 2016. They performed in the chapel of the Institut Catholique during the COV&R annual meeting in Paris last June.

James Alison in Australia

September 23, 2023, 9am-3pm, workshop in Melbourne

October 5, 2023, 7-9:30pm, public forum in Sydney

The Australian Girard Seminar will host of a series of events featuring leading Girardian scholar and pioneering theologian, Rev. Dr. James Alison.

A day-long workshop in Melbourne on Saturday, Sept. 23, “Living relationally with a sideways God: A mimetic anthropology of the Holy Spirit,” will focus on the practical implications of living out the insights of Rene Girard’s mimetic theory. James Alison will particularly explore the role of the Holy Spirit in the formation of virtue, humility, and conscience. The workshop is open to those of all levels, from mimetic theory beginners to those more familiar with Girard’s work. The workshop will begin with an introduction to Girard’s mimetic theory followed by a Q&A with James Alison. Register here ($140, concession $110).

An evening public forum in Sydney on Thursday, Oct. 5, will feature James Alison and fellow panelists:

- Dr Chris Fleming, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Western Sydney University (Moderator)

- Dr Elizabeth Farrelly, architecture critic, essayist, columnist and speaker

- Peter Hidden, AM, KC, Retired Justice of the Supreme Court of New South Wales

- Dr Samir Mahmoud, Islamic Scholar, Cambridge Muslim College UK

It will discuss the escalating crises and polarisations in modernity and how mimetic theory can contribute to understanding and addressing them. There is a general feeling that modernity is in crisis and that we move from one crisis to the next. It seems that we are constantly treating the symptoms—such as inflation, political polarisation, climate change, war, autocracy, social cohesion, mental health, social isolation, family breakdown and religious disaffiliation—but not getting to the core of our problems. It also seems, that as a result, that social cohesion is fraying and violence is becoming more public and extreme. This forum seeks to address the roots of modern crisis (which is manifest in the crises described above). In dialogue with Girard’s analysis and fundamental concepts, the forum will identify the drivers of modernity’s crisis and propose ways to address them. Tickets ($45, concession $30) available here.

Theology & Peace Annual Gathering

Chicago, Illinois

October 5-8, 2023

Plenary speakers will be Adam Ericksen, pastor of Clackamas United Christian Church, OR, and Executive Director of The Raven Foundation, and Dr. Sharon Baker Putt, Professor of Theology at Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, and author most recently of A NonViolent Theology of Love: Peacefully Confessing the Apostle’s Creed. Dr. Putt presented ideas from her newest book at the Theology & Peace Quarterly Speaker Series on February 23, 2023. Click here to view her presentation.

The meeting will be held at the Casa Iskali Our Lady of Guadalupe Campus located outside of Chicago. For complete information and registration, see the Theology & Peace website.

Be Not Conformed: René Girard at 100

NOVITATE Conference

Catholic University of America, Washington, DC

November 3, 2023 (note new date)

The first NOVITATE gathering will host a full day of presentations, panels, and dialogue, concluding with a dinner banquet to honor Girard’s legacy. Abstract submissions, due June 30, are welcome from anyone who is interested in the work of Girard and how it relates to the theme, “Be Not Conformed.” Conference presenters will have their registration fee waived and may receive an additional stipend for speaking. Apply to attend here.

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion

San Antonio, Texas

November 18-21, 2023

Registration is open for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion and the Society for Biblical Literature. COV&R is sponsoring two sessions:

Session 1: “Policing, Disability, and Conversion: Mimetic Theory in Contemporary Conversation”

Saturday morning, 90 minutes, time and location TBD

- Lyle Enright (UnRival Network), “Archimedes and René Girard: Cultivating and Replicating Mimetic Theory’s ‘Eureka Moment’ through Conversion Stories”

- Susan McElcheran (University of St. Michael’s College, Toronto), “Philosophies of Intellectual Disability in Conversation with Mimetic Theory”

- Charles Bellinger (Brite Divinity School), “Mimetic Theory and the Training of Police Officers”

Session 2: “Roundtable Session on Brian Robinette’s The Difference Nothing Makes. Creation, Christ, Contemplation”

Sunday morning, 2 hours, time and location TBD

Presider: Grant Kaplan (Saint Louis University)

Roundtable Participants:

- John Betz (University of Notre Dame)

- Amy Maxey (Oblate School of Theology)

- Chris Haw (University of Scranton)

- Grant Kaplan (Saint Louis University)

- Brian Robinette (Boston College)

Business meeting to follow the conclusion of this session.

Hommáge á René Girard

á l’occasion du centenaire de sa naissance

Paris / Avignon

December 14-17, 2023

This series of events in honor of René Girard on the centenary of his birth will feature two concerts by the Quatuor Girard and the Orchestre national Avignon-Provence, one at the Collège des Bernardins in Paris on December 14 and the other at the Palais des Papes in Avignon on December 17. The Paris concert will be followed the next day by a symposium at the Collège des Bernardins on the theme “René Girard, lecteur de l’écriture” with the participation of, among others, Benoît Chantre and Wolfgang Palaver. Further information is available here.

Desire among the Ruins:

Mimesis and the Crisis of Representation

COV&R Annual Meeting

Mexico City

June 26-29, 2024

Sponsored by Universidad Iberoamericana and hosted at the Colegio de San Ildefonso, COV&R’s annual meeting is being organized by board member Tania Checchi.

Filled with palaces and museums, Baroque churches and Art Deco buildings, Mexico City’s architectural history spans more than half a millennium, and new archeological discoveries are being made almost every year. San Ildefonso is located in the heart of Mexico City, just behind the Cathedral and next to the archeological site of what was the most important Pre-Hispanic religious center, Templo Mayor. Its situation at the crossroads of these two major cultural landmarks makes it the ideal venue for our conference.

The theme, “Desire among the Ruins: Mimesis and the Crisis of Representation,” opens up a dialogical and critical space for discussing what kind of motives, aspirations, and even hopes are inscribed into our need for images, taking into account from a mimetic point of view not only their sacrificial origin and their concomitant problematic status, but also their almost infinite capacity for transformation and renewal. The “ruins” of the title evoke both the actual archeological sites that will surround us during the conference, with their archaic echoes and demands, and the actual “ruin of representation” announced by Levinas à propos the crisis of traditional epistemologies and, most importantly, the crisis of meaning experienced from the 20th century on. Given this situation, we must ask along with René Girard: is desire condemned to walk among the ruins of its mimetic failures or can it open up to the truly desirable, an alterity whose frailty no violence can reduce or silence? And finally, can images be the vehicle of this conversion?

Mexico City offers comfortable accommodations at a wide range of prices. Mexican cuisine was declared a Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010 by UNESCO and Mexico City’s array of all Mexico’s traditional food as well as experimental new Mexican cuisine will make for an unforgettable cuilinary experience.

A full call for papers will be sent to COV&R members in late November or early December. Proposals related to the conference theme as well as other topics pertaining to mimetic theory will be welcome from anyone. Further information will be available on a conference website by early 2024, including details about travel, accommodations, travel grants, the Raymund Schwager essay competition, plenary speakers, and special programs taking advantage of the cultural riches in and around Mexico City.

Event Report

Reflections on COV&R’s Annual Meeting, 2023

Curtis Gruenler

This year’s conference theme looked both to the past, better understanding the development of René Girard’s work on 100th anniversary of his birth, and to the future of mimetic theory. Between these poles emerged a focus on Girard as a historical and political thinker. I’ve tried to organize a brief overview of most of the plenary presentations under these topics, without any attempt to discuss the parallel sessions—except to note how stimulating I found the ones I was able to attend, how much I wished I could have attended the others I heard about afterwards, and how encouraged I was by the number of new participants in COV&R that I got to hear and meet.

Girard’s first hundred years

Several presentations stressed the unity and coherence of Girard’s work from the start. Christine Orsini, vice president of conference co-host the Association Recherches Mimétiques, said that Girard’s work is not a “three-stage rocket”; rather, the first and last books each contain the other, as suggested by the original title of his first book, “Incarnation Romanesque.” The period surrounding what would be published as Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque, “romantic fiction and fictional truth,” was the focus of a preview by ARM president Benoît Chantre of the treasures from unpublished Girard archives and rich intellectual context forthcoming in his massive René Girard: Biographie. Trevor Cribben Merrill, translator and professor of French, carried this thread forward, arguing for an emergent sacramentalism, an identity of spiritual truth and literal truth, in the final chapters of A Theater of Envy: William Shakespeare.

Thomas Pavel, author, most recently, of The Lives of the Novel: A History, beautifully situated Girard within the development of literary scholarship (though perhaps in some ways that only literature teachers could really love) in order to highlight how far ahead of his time he was in connecting the interpersonal with the social, which criticism has tended to keep separate. For Sandor Goodhart, who studied under Girard, he is not just a reader but a reader of readings, of texts that are great because they are already interpreting prior texts. To read these great texts is to restore them to their context in order to recognize their prophetic function of framing choices we can make.

The session on “Oedipus and Beyond” encapsulated the movement from the past to the future of mimetic theory. Imitatio fellow Mark Anspach explicated, through Girard’s writings on Oedipus, how scapegoating was part of the mimetic model from the beginning. Goodhart showed in these same writings Girard’s development of his view that great literature challenges mythic narratives and exposes their violent origins. And COV&R president Martha Reineke looked beyond Oedipus to Sophocles’ Antigone for the possibility of sibling love as an alternative to sacrifice, a positive mimesis. Pavel made a similar gesture toward models of good desire in the depiction of giving in Little Dorritt by Charles Dickens.

The future of mimetic theory

Jean-Michel Oughourlian, collaborator with Girard on Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World and pioneer in developing its interdividual psychology, gave a conspectus of the key tenets that distinguish this approach. Among the reference points he gave for a “new, mimetic psychiatry” was his “impression” that “every neuron has a mirror function”—that is, I take it, that imitation is basic to every mental function in ways that neuroscience has still only begun to fathom.

Andreas Wilmes, editor-in-chief of the Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence, raised concerns about the increasingly technological conception of violence and peace and suggested this has the effect of sacralizing technology. Jean-Pierre Dupuy framed his argument about the paradoxes of nuclear deterrence as part of his continuing dialogue with Girard’s understanding of the escalation to extremes in Battling to the End. An English translation of Dupuy’s The War That Must Not Occur is due out next month.

The philosopher Frédéric Worms, Director at the École Normale Supérieure, Paris, offered a comparison of Girard and his friend Michel Serres as the only two thinkers to confront the problem of “radical violence.” Whereas Serres came to the problem through Girard, he also went farther in building a philosophy of communication to oppose it. Both locate the structure of violence in human relationships and seek to answer it there. While Girard’s approach to individual relationships looked to Christian faith, Serres looks more broadly to love and friendship with the support of the political order—another echo of the Girardian theme of the connection between the interpersonal and the social.

Surprise guest Peter Thiel, entrepreneur and benefactor of COV&R and ARM, offered a tour de force of six things that are “not enough” to answer current stagnation and other looming threats, whether the breakdown of order or its forceful imposition. The inadequacy of all six, philosophy, scapegoating, the Christian catechon, varieties of modernity, decadence, and nihilism, could be seen as extensions of Girardian critiques. When Worms, the host of Thiel’s session, asked what would then be enough—or if not enough, at least necessary and worth keeping—it was reassuring not to hear anything about technology, adaptation, or the free market. Thiel’s reply, that it would be tempting to think that mimesis could be channeled for good in a non-Christian way, called to mind the conclusion of Worms’s own presentation earlier that day.

Wolfgang Palaver of the University of Innsbruck, no doubt the most well-informed person about work applying mimetic theory, concluded the meeting by drawing attention to the volume of recent publications. He highlighted work in archeology, anthropology, and world religions, but also noted one that fits the theme of Girard as a historical and political thinker: the 2019 book by Stephen Holmes and Ian Krastev, The Light That Failed: Why the West Is Losing the Fight for Democracy, which forms from Girard a concept of “political imitation” in order to explain the post-Cold War failure of liberalism around the world through the resentment generated by the imperative to imitate the West.

Girard as historical and political thinker

As Paul Dumouchel, one of the organizers of the meeting, explained, Girard explored the interrelation between literary change and sociopolitical change by seeing both in light of interpersonal relations. From this arose his interest in political issues, though not partisan politics, as well as in the influence of institutional structures on interpersonal relations.

COV&R board member Marinela Blaj, from Alexandru Ioan Cuza University in Romania, reached deep into the cultural past to show the methodology she has developed for applying mimetic theory to conflict between nations through her study of one of the original nation-forming conflicts, the wars between Rome and Carthage.

Bringing things very much up to the present, Elisabetta Brighi of the University of Westminster explored the potential for fruitful dialogue between mimetic theory and a new focus in terrorism studies on the cooperative function of terrorism, how it can be driven by “pro-social acting for the sake of others.” She called for greater contextualization of mimetic theory in order to give it a richer sense of historical development, contingency, and irony.

Humility

Perhaps the meeting’s most fitting tribute to Girard’s legacy can be seen in the fact that it was bookended by a focus on humility. This was the topic of James Alison’s opening talk (a version of which is available at jamesalison.com), and Palaver began his concluding outlook with a reminder that mimetic theory’s explanatory power is inseparable from its humility as a hypothesis rather than a system, as seen in Girard’s own self-corrections. As Alison put it, scapegoating is available everywhere, thus also opportunities to lose gracefully.

Or as Oughourlian observed, “One thing above all cannot be shared: power.” And yet there was something akin to power that we shared in at the meeting. Perhaps part of the future of mimetic theory is to continue the work of articulating what that is in order to hold it up as something to be sought instead.

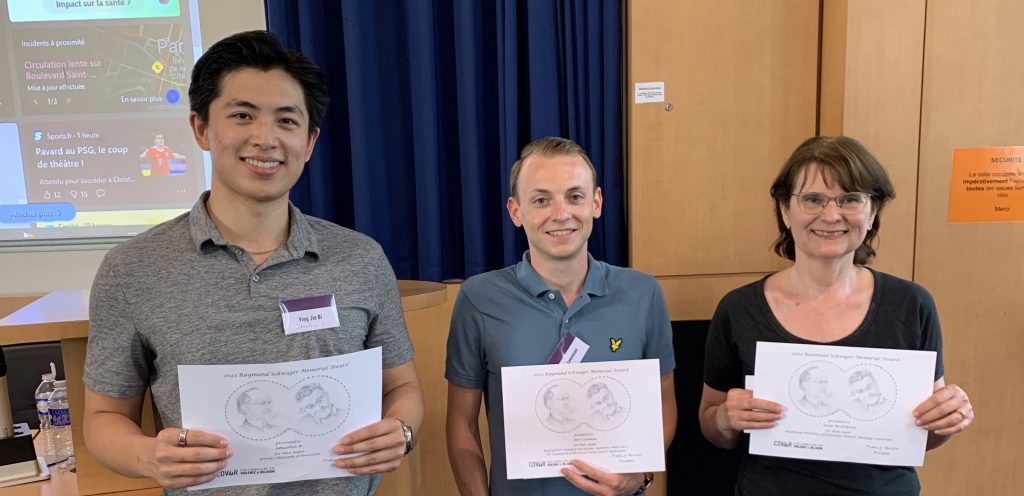

Editors Note: The list of recent winners of the Raymund Schwager Award is now available.

Letter from Avignon

New Girard Society Founded

Mark R. Anspach

In the summer of 2019, a new organization, “La Société des amis de Joseph & René Girard,” was created in Avignon, the Provençal town in the south of France where René was born and raised and where his father, Joseph, was curator of the Palais des Papes. Avignon is also the place where René finished writing his first book, Mensonge romantique (Deceit, Desire and the Novel). After co-founding in 1962 the “Institut d’Avignon,” the French summer program of Bryn Mawr college, René returned to his native city every year for more than 20 years to teach courses there in June and July.

Members of COV&R will be happy to learn that a new generation of Girards is carrying on the family legacy. Marie Girard, René’s great-niece, is the president, and her brother Benoît Girard, a historian like great-grandfather Joseph, edits the Society’s publications. They enlisted the support of René’s wife Martha and his sister Marie as well as that of medieval historian Michel Zink, the successor to René’s chair at the Académie française, who serves as honorary president. The board of directors includes René’s three children, Daniel, Martin, and Mary.

As one of the Society’s first initiatives, Marie Girard and vice-president Alexandre Avril traveled in November 2019 to Stanford, where they spent two weeks at Martha and René’s house cataloging the contents of his personal library. Many of the volumes are annotated by René Girard or inscribed to him by well-known writers such as Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, or Milan Kundera, who, when he gave Girard a copy of his book on the art of the novel, identified himself as a “longtime admirer.”

The Society has organized a number of events this year to mark the centennial of Girard’s birth. An original musical composition will be performed in December by the Quatuor Girard and the Orchestre national Avignon-Provence at the Collège des Bernardins in Paris on December 14 and the Palais des Papes in Avignon on December 17. The Paris concert will be followed the next day by a symposium at the Collège des Bernardins on the theme “René Girard, lecteur de l’écriture” with the participation of, among others, Benoît Chantre and Wolfgang Palaver.

Finally, the Society is launching a new French-language journal, Antigone. The inaugural issue is slated to include texts by Lucien Scubla and Sandor Goodhart as well as the bishop of Nanterre and the rector of the Bordeaux mosque, along with an interview with Michel Zink, “René Girard, le Moyen Age et nous.”

Anyone interested will find more information on the journal, the centennial events, and the Society’s other activities on the French website sajrenegirard.fr.

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the Bulletin editor, Curtis Gruenler.

All Desire Is a Desire for Being: Essential Writings

Curtis Gruenler

Hope College

René Girard

Edited by Cynthia L. Haven

Penguin Classics, 2023

317 pages

Since 1996, English-language readers interested in an introductory overview of the work of René Girard have been well served by The Girard Reader, edited by James Williams and made up mostly of excerpts from Girard’s books that, together, “cover all the basic aspects of Girard’s theory.” Cynthia Haven’s selections in All Desire Is a Desire for Being will serve a similar purpose but with the great difference that almost all of the selections were written to stand alone. While the Reader is packaged for a primarily academic audience, All Desire appears in the Penguin Classics, the most prestigious series in English of books for all educated readers—a sign that Girard’s own work has reached the status of, as he once put it, being read as literature no matter what discipline of knowledge it comes from. During the week it was published, I happened to be in a bookstore on a tourist-oriented street in Galway, Ireland, and, curious how far this new level of visibility might reach, I looked under literature and didn’t see it. But when I asked, lo and behold, there it was, in a small section devoted to philosophy.

Haven’s introduction to All Desire aims at anyone interested in understanding themselves and the world. My go-to piece on Girard and mimetic theory for students of late has been the introduction to Evolution of Desire, Haven’s biography of Girard, but this is even better: concise, accessible, weaving the basic facts of Girard’s life into a personal sense of encounter with the man and his ideas. Haven adapted some of its presentation of Girard’s ideas in a piece just published on Zócalo Public Square. She also previously edited a collection of interviews, Conversations with René Girard: Prophet of Envy, published by Bloomsbury in 2020 and reviewed by COV&R member Chris Fleming for the Los Angeles Review of Books.

A handful of the selections here are given a brief editorial introduction to set their context, but these are kept to a minimum. The back matter comprises a brief chronology of Girard’s life, a list of his books available in English, sources of the selections, and a thorough index.

The selections themselves were originally published for a wide variety of audiences, many of them in out of the way places, so that even someone who already owns all of Girard’s other books will likely want this one too. Perhaps the most surprising source is Ballet Review, where Girard published “Scandal and the Dance: Salome in the Gospel of Mark.” Its argument is also part of a chapter in The Scapegoat, but this version expands some points of explication and offers more on dance and on the arts in general. Plus, like all the pieces here, it assumes little or no prior knowledge of Girard’s work or the terminology of mimetic theory—certainly no more than Haven gives in her introduction.

Some of the selections were written for very broad audiences. The first, a brief two pages titled “Conflict” published in Stanford Magazine in 1986, not long after Girard took up his final academic post there, does little more than urge the importance of the fundamental question about human violence that runs through his work. The second, only a page longer, translated by Haven as “Violence and Foundational Myths in Human Societies” from Le Monde in 2008, gives a helpful overview of Girard’s thinking about religion. Somewhat longer at 13 pages, “Violence and Religion: Cause or Effect?” (from The Hedgehog Review in 2004) introduces his understanding of myth, archaic religion, and the Bible more fully. The best overview of Girard’s thought here, and perhaps anywhere, also a succinct 13 pages, is “Victims, Violence, and Christianity,” originally given as a lecture at Oxford in 1997 and published in The Month, which ceased publication soon after.

One of the highlights is “The Mystic of Neuilly,” the address Girard gave when he was received into the French Academy in 2005, translated for this collection by Trevor Cribben Merrill. By tradition, the topic of such an address is the previous holder of the same chair, in this case a Dominican priest named Ambroise-Marie Carré. Girard’s reading of Father Carré’s writings is, as Haven puts it in her introduction, “sublime,” one of his most searching explorations of the experience of conversion. All the more moving is the care with which he addresses an audience that no doubt represented a great range of perspectives on such matters. The only nod to mimetic theory comes in the very last sentence—I won’t spoil it.

Girard’s own conversion is at the center of a generous excerpt here from his conversations with Michel Treguer published as When These Things Begin. It also includes a classic rendition of Girard’s brilliant interpretation of the story of the woman caught in adultery from the Gospel of John.

Two other selections, besides the one on Salome, also focus on biblical texts. “Peter’s Denial and the Question of Mimesis,” originally published in the Notre Dame English Journal (now Religion & Literature),shares its scriptural analysis with another chapter from The Scapegoat, but here it is framed by Girard’s important comments on literary mimesis and Erich Auerbach’s classic account of it in his book called Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Two brief chapters from Job: The Victim of His People emphasize how this text from the Hebrew Scriptures can illuminate the dynamics of “totalitarian” societies, in ways that have not lost relevance even if the nuances of political labels have shifted since the early 1980s, when these chapters were written.

Treguer says to Girard at one point, “Your extreme rhetorical dexterity makes me a little uneasy” (168), and many of the selections here showcase the uses of that dexterity. In “The Founding Murder in the Philosophy of Nietzsche,” previously published in Violence and Truth with other talks from a 1983 symposium, Girard adopts a playful pose of someone obsessed by an idea and searching the work of the author most likely to contradict it, only to find it confirmed yet again.

Several selections focus on literary texts. Two appeared in Œdipe mimétique by Mark Anspach (2010) and are translated here for the first time: a preface in which Girard uses the example of Oedipus to introduce the main insights of mimetic theory and a brief conversation in which Anspach draws him out on some of the potentially confusing points of its application to Oedipus. An early and challenging article on Camus does not bring mimetic theory to bear but rather exemplifies Girard’s interest in a kind of conversion experience undergone by great authors, like those he had just written about in his first book. Girard argues that La Chute, Camus’s last novel, puts on trial, as it were, the Camus who had written his more famous, early L’Etranger and is thus the greater work. Essays on A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Julius Caesar, two of the plays that get the most attention in Girard’s A Theater of Envy: William Shakespeare, give accessible demonstrations of how he relocates the true greatness of the incomparable dramatist.

In the wonderful “Literature and Christianity: A Personal View,” a talk given at the national meeting of the Modern Language Association (a similar talk was included in his collection Mimesis and Theory), Girard surveys his work as a literary scholar, including its importance for his own conversion. It is one of the best invitations to this aspect of his thought. A short essay “On Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ,” originally published in the French news magazine Le Figaro, takes its focus on the controversial 2004 film as an occasion for reflections on violence, representations of violence, and the Gospels that, as with all of Girard’s work, does not easily align with one side or the other of familiar cultural divides.

In “Belonging” (which already appeared in Contagion, volume 23, 2016, where a note explains the translation of the original title, “Les appartenences”), Girard articulates the relevance of his insights to current social concerns and controversies in a way that spares the usual vocabulary of mimetic theory. Instead it feels as if, even though he was entering his ninth decade when he first gave this talk, he was still trying new ways to get his ideas across.

The final selection consists of 172 “Maxims” culled from throughout Girard’s works. These bring out at once the penetration of his insights and his literary gifts in expressing them. For those already familiar with his work, they will serve to bring its many facets quickly and pleasingly to mind. It is hard to know how they may strike someone new to Girard, but I imagine they would want to know more about where these little bombshells come from. My favorite today (one of many I don’t remember seeing before): “Our unending discords are the ransom of our freedom.” Haven would like to collect more; you’re invited to send your favorites to her here.

One major topic likely to come to mind for many readers new to Girard but not represented here is how he might see other major world religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam, in comparison to his reading of the Judeo-Christian scriptures. The introduction to Mimetic Theory and World Religions, edited by Wolfgang Palaver and Richard Schenk (reviewed here), summarizes the main places he addresses them.

I had wondered how useful this collection might be for teaching. I plan to give it a try in a capstone seminar for undergraduate literature majors, in which Girard will be a major focus, but at lower levels I expect to stick with most of the short pieces from other sources that I already use while adding some of these. Everyone who teaches or leads discussions on Girard, however, will want to consider the riches Haven has gathered.

Unfortunately there are some transcription errors, mostly in the article on Julius Caesar. Most of these are omissions of a few words; the original is available on JSTOR. Also, on page 154, line 2, “presents” should be “prevents.” Let us hope this volume will have more than enough lives for these errors to be corrected.

Note that the book will not be officially released by Penguin U.S. until 2024. For now it is shipping from the U.K. and can be ordered through the Penguin U.K. web page. If you are trying to order from Amazon in the U.S., beware of a bootleg page that some have apparently had trouble with.

The Empire of Value: A New Foundation for Economics

Mark R. Anspach

André Orléan, translated by M. B. DeBevoise

MIT Press, 2014

x + 350 pages

Ask anyone what economics is about. The answer will probably boil down to a single word: money. From the Wall Street trader to the sidewalk panhandler, everybody is chasing after the same thing. Money is the universal object of desire, the one thing of value on which all agree. Except economists. If you ask professional economists what their discipline is about, you are unlikely to get such a crass answer.

Mainstream economists are hopeless romantics. They believe in the enduring value of things—things people strive to possess because they are intrinsically desirable. Economists generally refuse to acknowledge the central importance of money. They conceive of money in purely instrumental terms as an accounting device and a useful tool to facilitate the exchange of scarce goods.

Economists have differed over the years as to what makes those goods valuable. For classical economists from Adam Smith to Karl Marx, value is rooted in the quantity of labor put into producing a good. For today’s neoclassical economists, value derives from the amount of utility that the same good yields the consumer. But that difference is secondary for André Orléan. In The Empire of Value, this eminent French economist contests the very notion that things have an intrinsic value and challenges the absolute dominion (the old meaning of “empire”) that this dogma exercises over his discipline.

However economists have defined value, Orléan argues, they have always fallen into the trap of seeing it as an objective property belonging to the goods themselves. In this traditional conception, money is treated as a mere veil obscuring the real workings of the economy—a veil that, as Joseph Schumpeter puts it in a characteristic passage of his History of Economic Analysis quoted by Orléan (17), “must be drawn aside.” For this reason, economics textbooks typically begin by describing market exchange as if it were essentially a form of barter in which one good is traded for another. “Money prices must give way,” Schumpeter continues, “to the exchange ratios between the commodities that are the really important thing ‘behind’ money prices.”

For André Orléan, the search for a true value “behind” the money price is a wild goose chase. Money itself is the “really important thing”: “the relation to commodities is always a monetary relation.” Money is the founding institution of the market economy; the ceaseless quest for money its defining feature. The universe of the market is “governed by a single, overpowering desire—the desire for money, to which all other desires are subordinate.” This fascination with money “is at the heart of every market economy, its primordial and inexhaustible source of energy” (109-11).

Some anglophone COV&R members may remember Orléan’s early article “Money and Mimetic Speculation” from the collective volume Violence and Truth (Stanford, 1988). Since then, he has published a series of influential works on money in France. The Empire of Value is a revised and enlarged translation of L’Empire de la valeur, which first came out in 2011 and won the Paul Ricoeur Prize. The English edition includes two bonus chapters that lay out the clearest and most convincing analysis of the 2007-2008 financial crisis that we have ever seen. With a new crisis visible on the horizon, The Empire of Value is a timely book to read now. But it is also timeless, a book for all seasons, for it uses mimetic theory to construct a framework of analysis valid for periods of stability and crisis alike. Although written mainly for economists, the book is accessible enough to repay careful study by laypersons.

Most readers will agree that Orléan’s emphasis on the desire for money accurately reflects the world we live in. It is surely a more realistic point of departure for understanding the market than the idea of a barter economy with money added as an afterthought to oil the wheels of exchange. As a number of authors have shown, from Marcel Mauss in The Gift to Marshall Sahlins in Stone Age Economics, premonetary economies are based primarily on gift exchange.

The type of barter posited by economists, where isolated individuals meet their needs by trading useful goods back and forth, was for most of human history the exception rather than the rule. Far from facilitating transactions in which people already engage spontaneously, money institutes a radically new form of exchange; it severs the bonds of solidarity that traditionally unite the members of a group, thereby creating the isolated individual agents whose existence is the premise of economic theory. Orléan calls this state of affairs market isolation.

In the state of market isolation, individuals are cut off not only from each other, but from the means of subsistence. As a result, they must depend on others to survive, and yet they cannot directly coordinate their actions with one another. In this strange situation, relations among people are ostensibly mediated by the circulation of things. The commodities that folks buy and sell occupy center stage; they seem to dominate the action, relegating the interaction of the people themselves to the shadows. This is what Marx called commodity fetishism. Orléan (26) quotes Marx’s famous words: “the definite social relation between men themselves” assumes “the fantastic form of a relation among things.”

In neoclassical economics, consumers rank the things offered in the marketplace against each other, evaluating them precisely in terms of their own individual preferences. A consumer’s relative preferences for different baskets of potential goods are specified mathematically in the form of a utility function. Each consumer has their own personal utility function based on the satisfaction or subjective utility that given goods can be expected to provide that particular individual. Preferences are therefore conventionally held to be fixed and “exogenous,” meaning that the formation of those preferences is external to the operation of the market.

“Such preferences are determined by an intimate encounter between the consumer and the things he desires, without any reference to what other people do,” Orléan (38) writes —“neither what they consume, nor what they desire” (these last words appear only in the French text). The relations among people remain in the background, leaving the spotlight on the tête-à-tête between the individual consumer and the object.

Hopeless romantics that they are, mainstream economists “imagine that individual agents know exactly what they want.” The consumers of neoclassical theory are supposed to be the absolute masters of their own desires, “able by force of will alone to select, from the undifferentiated mass of objects,” those worthy of their favor. As Orléan (50-51) observes, this illusory picture of individual autonomy corresponds to what René Girard calls the “romantic lie.”

Quoting from Girard a key passage on desire, Orléan (51) applies it to economists: “When modern theorists envisage man as a being who knows what he wants… they may simply have failed to perceive the domain in which human uncertainty is most extreme. Once his basic needs are satisfied (indeed, sometimes even before), man is subject to intense desires, though he may not know precisely for what. The reason is that he desires being, something he himself lacks and which some other person seems to possess. The subject thus looks to that other person to inform him of what he should desire in order to acquire that being.”

These lines deserve to be quoted in the opening chapter of every introductory textbook on economics. They restore to the foreground the relations among people that the state of market isolation obscures. The fact that individuals do not coordinate with others the actions they take in the marketplace does not mean that those actions are not profoundly influenced by others. Individual consumer preferences seldom arise in isolation; they are constantly subject to the imitation of models.

But recognizing the mimetic nature of desire is only the first step. Orléan immediately goes on to present the two different regimes of mimetic desire that Girard dubs internal and external mediation. Introducing this distinction proves to be a decisive theoretical move. It allows Orléan to account for both the successes and failures of mainstream economics. This in itself is a signal achievement.

Radical critics often leave the impression that neoclassical theory is utterly out of touch with economic reality. There is ample justification for this criticism, yet it begs the question of why anyone in their right mind would take such a theory seriously. Economic orthodoxy clearly serves an ideological function, but wouldn’t it fail even on those terms if its lack of realism were too obvious? Orléan suggests that the assumptions of neoclassical theory hold up fairly well as long as external mediation prevails. It is when they are confronted with internal mediation that they fall apart.

Orléan shows that the validity of the law of supply and demand depends imperatively on banishing internal mediation. When preferences are fixed and exogenous, consumers have no need to imitate what others do because they already know what objects are worth to them. If the price of a given good rises “too high” compared to the utility consumers expect to derive from it, they will respond by buying less of it, and producers will respond to this drop in demand by lowering their prices again. In this scenario, the falling demand provoked by a rising price constitutes negative feedback that encourages a return to equilibrium.

But the opposite scenario is also possible. What if, rather than sticking doggedly to their own individual utility function, buyers let their preferences be swayed by the behavior of others? “To the extent that the rise in price expresses an increased desire on the part of others to possess a given good, the effect is to intensify the mimetic agent’s own desire” (54). This is what happens with fashionable luxury items, popular new technologies, hot stocks, or fast-appreciating real estate. Here we enter the world of internal mediation, where individuals “no longer know what constitutes worth” and it becomes rational to imitate the desires of others (60).

When a high price is seen as a measure of desirability, the law of supply and demand “no longer holds: the increase in price, rather than causing demand to fall, makes it stronger, which leads to a new rise in price, pushing it still further from its equilibrium level.” The moderating action of negative feedback gives way to the amplifying stimulus of positive feedback, creating a snowball effect. “A perverse dynamic of price and demand is therefore set in motion that, if it is not halted in time, threatens to undermine the entire economic system” (53-54). In the book’s spectacular closing chapters, Orléan demonstrates that precisely this type of dynamic was at work in the subprime crisis, which, though it came on the heels of history’s biggest housing bubble, still caught the majority of economists by surprise.

Mainstream economists are most comfortable with the stability afforded by external mediation. Because they do not understand the way internal mediation favors an escalation to extremes, they perpetually underestimate the threat of a new economic crisis. By contrast, the “strength of the mimetic hypothesis” lies in its ability to accommodate different types of interaction within the same unified framework. “Imitation is a source of stability” when it converges durably on a single model whose legitimacy goes unchallenged. But when “the model loses its position of exteriority,” imitation “produces a contagious dynamic. The mimetic hypothesis therefore makes it possible to analyze both stability and instability, as well as transitions from one state to the other” (60).

When it comes to external mediation, Orléan shows that the neoclassical and Girardian approaches are not incompatible. In external mediation, the model remains aloof from the person doing the imitating, whom we will call, following Girard, the “disciple.” All the imitation is one-way. The disciple imitates the model’s desire, but the model does not imitate the disciple’s desire. Indeed, the disciple has no influence whatsoever on the model. In this sense, there is no interaction between them. Given the lack of interaction, the absence of mutual influence, there is, as Orléan points out, a formal analogy between Girard’s description of external mediation and the neoclassical picture of consumers making decisions in splendid isolation.

This formal analogy exists despite the divergence in underlying assumptions. The consumer of neoclassical theory is nobody’s disciple. Consumers are deemed sovereign, the masters of their own desires. Girardian consumers in the grip of mimetic desire are decidedly not sovereign. In practice, however, a theorist may get away with treating their desires or preferences as if they were fixed and exogenous when those preferences result from imitation of a model that is out of reach rather than from interaction with other consumers in the marketplace.

In these circumstances, there are two possible ways to explain the existence of an exogenous utility function: it is either the consequence of preferences that are naturally stable because they are anchored in a sovereign individual, or else it is the consequence of imitating an external mediator. Orléan is thus able to account for the findings of mainstream economics from his own Girardian perspective. The importance of this is worth underscoring. It means that mimetic theory can encompass the results of mainstream economics within a broader theoretical framework, so that neoclassical consumer behavior is understood as a special case of mimetic behavior encountered in the presence of external mediation.

Who are the external mediators? The Girardian reader may think of prestigious individuals whom throngs of strangers admire from afar: actors, singers, sports stars, billionaires… All these examples are relevant. Orléan devotes much attention to the question of prestige. But he also has something else in mind: not a “who” but a “what.” In the state of market isolation, individual agents treat the values that emerge from their interaction as if they had an independent existence. At the most fundamental level, then, external mediation is something built into the market system itself.

We can see this most clearly in the model of general equilibrium proposed by the French economist Léon Walras, one of the pioneers of neoclassical economics. In Walras’s model, prices emerge from an auction-style bidding process in which they are progressively adjusted in order to balance supply and demand. Price formation is “wholly external to individuals.” Each participant in the auction operates in total isolation; the “transactions take place without agents ever entering into contact with one another,” Orléan writes (44-45). How is this possible? Thanks to the intervention of an imaginary figure who guides the process from the outside: the auctioneer. Here the “what” of external mediation is significantly embodied in a mythical “who.”

But the role of external mediator is also played by commodities themselves once they are conceived as possessing intrinsic value. Relations among people can then be mediated by things; these act like a “third party” that separates individuals and “dispenses with any need for them to be in direct contact with one another” (59). The neoclassical vision of an encounter between individuals equipped with fixed preferences and objects endowed with utilitarian value is not entirely baseless for Orléan. Rather, he sees it as the transitory result of a particular mimetic regime that emerges when preferences and values have been stabilized.

This regime is more precarious than it seems. Utility and preferences are not objective facts established once and for all, Orléan insists. “They are social constructions that, taken together, have the function of preserving and protecting the state of market isolation by blocking the emergence of mimetic rivalries” (87). Social constructions endure as long as faith in them persists. The best illustration of this is money. The value of money depends on people’s belief in it. This unspoken truth bursts out into the open when a loss of confidence provokes a currency crisis. But when a country’s currency appears strong, people take for granted the value of their money and perceive it as independent of their own interaction.

In the final analysis, money is the most essential external mediator in the market economy. It is what allows for transactions between individuals who are strangers to each other. Everyone desires money because everyone knows that everyone else desires it. The “unanimous desire of market actors for money” is what renders exchange possible (124). Money is the expression of a universal mimetic convergence on a single standard of value that is thereby invested with the “power of the multitude.” Once this power assumes the form of the chosen monetary object, it is “distanced from itself and transfigured.” The value that the collectivity bestows on money now appears to be “a part of its nature” (147).

What about the value of ordinary commodities? If their value is not, as traditional economic theory posits, an objective property of the goods themselves, what is its source? How should it be defined? Orléan’s answer is as simple and straightforward as it is surprising: “The value of a good is measured by the quantity of money that this good makes it possible to acquire, that is, by its price. From this it follows that price and value are, at bottom, one and the same thing” (124).

As anyone not a professional economist will tell you, economic value all comes down to money. This view is hardly romantic. At first blush, it may even sound cynical. But in the context of Orléan’s theory, the opposite is true. For money itself, as we just saw, is a collective creation. It draws its power from us. “Value does not reside in objects,” Orléan concludes. “It is produced by human beings acting in concert with one another” (324). The ultimate source of value is none other than the human community.

Every economist—and everyone who wants to understand why we keep blundering from one financial crisis to another—should read André Orléan’s audacious and ambitious book. The Empire of Value lives up to its promise of rebuilding economic theory on sounder foundations. And it does so through a strikingly original use of René Girard’s mimetic theory.

Law’s Sacrifice: Approaching the Problem

of Sacrifice in Law, Literature, and Philosophy

Andrew McKenna

Loyola University Chicago

Edited by Brian W. Nail and Jeffrey A. Ellsworth

Edited by Brian W. Nail and Jeffrey A. Ellsworth

Routledge, 2020

197 pages

The aim of this assembly of twelve essays is plainly stated at the outset: “This volume explores the relationships between law and sacrifice, focusing in particular on how the two institutions relate to questions of violence, power, political agency, and the future of liberal democracies in an era of populist political unrest” (1). These questions have ever preoccupied thinkers since the ancient Greeks; they lie at the center of Renaissance speculation on government, with Hobbes and Machiavelli especially, where human violence is central to their concerns about political foundations. To reorganize these topics around the notion of sacrifice is a welcome effort, as it engages wide-ranging issues raised by current anthropology, including René Girard’s mimetic hypothesis of social organization as originating in sacrificial scapegoating. The sacrificial origin of kingship has long been the focus of anthropological enquiry. Modern social sciences in our Western “disenchanted” culture have detected myriad ersatz versions for ultimately groundless authorizations.

So it is no surprise that Jacques Derrida figures importantly in several of the essays here; on every occasion he has “deconstructed” our customary notions of origin, foundation, and thereby legitimacy, and rationality itself. In his “Introduction,” the editor cites Derrida’s lengthy essay, “The Force of Law,” which first appeared, along with prominent adepts at deconstruction, in the distinguished Cardozo Law Review in 1990. It still bears rereading, not least for taking us back to the reflections of Montaigne, who insists on the “mystic foundation” of law; and Pascal, who follows his Renaissance mentor in this, and locates this “mystique” in human violence. Under the heading “Justice. Force,” he allows that the latter inevitably prevails in any contest; justice without force being powerless, ”impuissant.” Pascal sees the necessity and impossibility of “to put justice end force together,” because, Derrida notes, “justice demands, as justice, recourse to force” (937). The necessity of force is implied, then, in the “juste” in justice (author’s italics emphasizing the idea of getting justice right). Heraclitus got it right the first time—and for all time: “Violence [polemos] is the father and king of all. Some it makes gods, others men; some slaves, and others free” (53). Difference is the matrix of culture and violence is the matrix of difference.

The editor’s introduction gives a good account of Girard’s ideas, which receive sustained attention in “Sacrifice and the Origin of Law,” Wolfgang Palaver’s clear and compact discussion of the role of sacrifice that we don’t wish to acknowledge in legal institutions and practices. Johan Van Der Walt’s lengthy and somewhat meandering contribution, “The Gift of Time and the Hour of Sacrifice,” brings Girard into conversation with the anthropologies of Robertson-Smith on ancient religion, of Hubert and Mauss on gift rituals, and of Georges Bataille’s reflections on Eros and potlatch. Carl Schmitt’s political theology is also engaged here—and often elsewhere; he is a convenient straw man, a foil for the left: there are Derridians and Girardians aplenty, but no Schmittians anywhere to be found, no subscribers to the ideas of this former legal functionary of the Third Reich. Van Der Walt concludes with Derrida’s idea of democracy as something that is always to come, “à venir”—we have to give it time (“donner le temps”). His aim is to account for the current resurgence of populist politics, its violent haste and intolerance of ambiguity and uncertainty, of the complexity, in a word, that political liberalism, on the contrary, allows for. It’s a matter of trust and risk, which for some theologians go by the name of “messianic patience,” as opposed to sweeping and strident guarantees.

Critical scrutiny of liberal democracy is in turn undertaken by Richard Mailey, who, in “Sacrificial Liberalism,” stages a virtual debate between John Rawls and Carl Schmitt. His subtitle, “The Politics of Zeal and its Selective Denial in Rawl’s Political Liberalism” pretty much summarizes his argument. Mailey’s point is to de-differentiate them, a classic deconstructive operation. Where Schmitt’s political theology, founded upon the friend/enemy dyad, is openly sacrificial, as his commentators never fail to point out, Rawls’s criterion of public “reasonableness” is indicted as a “‘God’ concept,” a species of “secular fundamentalism” (159). This is a criticism bolstered by recourse to Chantal Mouffe, who has warned us away from hegemonic proclivities of democratic liberalism. “Zeal” as defined by Rawls herein involves “a relentless struggle to win the world for the whole truth” (153). Girardian epistemology, which makes just such a claim “since the foundation of the world,” is not invited to this debate, but readers can find a vigorous exposition of it in Paul Dumouchel‘s Barren Sacrifice, which is helpfully consulted in a few other essays.

Girard does not figure either in Jeffrey A. Ellsworth’s essay, “The Sacrifice of Law’s Madness,” which examines the unapologetic lawlessness of the Bundy family’s armed resistance to the Bureau of Land Management in 2014. Ellsworth skewers its “crippled epistemology” (172), which also fuels the motivations of the Oklahoma City bomber. Ellsworth rightly deplores the “widespread legal ignorance in the US,” and in turn calls for more public legal education. By “madness” is meant the redemptive urgency of terrorism, a “counter narrative to dominant legal reality” (183). Of course, there is no need of mimetic theory to establish such a difference as that in a culture beset by a veritable plague of gun violence throughout.

In “(Misguided) Self-transcendance and the Imagination of Sacrifice,” Arthur Cools relies principally on the thematics spelled out in Moshe Halbertals in On Sacrifice (2012), while focusing on some essays of Maurice Blanchot that bring writing and revolution into close association—though not obviously to the benefit of the public weal judging by Cools’s concluding statement: “The possibility Blanchot is pointing at is that of a sacrifice which is continuously transgressive and excessive; sacrifice made of rejecting what is given, breaking laws, crossing over limits, not following the rules at [sic] the point of becoming meaningless, of losing everything, of disappearing but always captivating, singular and recursive” (56). That might strike readers as a recipe for anarchy as favored by the early surrealists and more recently by the paving stone throwing of Parisian soixante-huitards. It could also bring to mind the undifferentiating chaos incited by Dionysus in Euripides’ Bacchae, which Girard scrutinizes in Violence and the Sacred. But Cools, like all the other contributors, does not look to literary masterpieces to illustrate or explain his argumentation; instead he calls upon Blanchot’s reading of the myth of Orpheus, celebrating “the boundless impulse of desire” (55). For what it’s worth, Girard’s reading of Euripides, indeed his entire oeuvre, is a properly anthropological critique of just such an “impulse” as that. But perhaps I am misreading the author, for elsewhere he aligns with Halbertals’s claims against “misguided transcendence,” concerning “the role of imagination not only as a support for representing goals and overestimating values, but much more as the negative power which rejects God and world as such and which reveals its boundless and devastating play in the void that results from this rejection” (56). That strikes me as more in line with Girard’s thinking, especially his very high estimation of literary masterpieces, as in Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, that expose our fatuous delusions about desire. Culture, like nature, abhors a vacuum: what fills this “void” is violence, which is resisted by still more violence. Yeats’s image of a “widening gyre” in “The Second Coming” daily takes on real historical pertinence.

In “Law, Authority, and the Sovereign Exception: The (Im)possibility of Political Agency,” Richard Hajarizadeh undertakes to compare and contrast Derrida’s “Force of Law” with Jacques Rancière’s Disagreement Politics and Philosophy, and this with a heavy assist from Giorgio Agamben, Michel Foucault, and Walter Benjamin, in order to conclude upon “law’s self de(con)struction” (106). In sum, “the law is its own negation” (109). This conclusion is not surprising, as it follows a Derridean model to examine concepts not in order to clearly differentiate them from their opposites, but instead to expose their internal contradictions, their difference from themselves, their parasitical relation to what they oppose. No examples, historical or textual, are adduced to illustrate this argument, so perhaps we don’t have to worry about what to do about it.

In “A We not Modeled on the I: The Law of Law,” Samuel A. Kimball also recruits Derrida to expose, also contra Schmitt, the self-contradictions embedded in legal foundations, as “Auto-Affective Self-Illusion” (68), though he confuses the explicitly divine sanction for violence in our Declaration of Independence with the coolly temperate and technical language of our Constitution. On the other hand, he makes good use of Girard’s anti-sacrificial critique in his reading of the role of Poseidon in the Odyssey, which he links with the Pauline paradox in “the imperative to love the one who is other (Rom.13:7).” For Kimball, “This imperative commands all other imperatives. Like the law of law, which is therefore law without law, the imperative of all imperatives is without imperative” (75). No recourse to biblical scholarship or mainstream theology is engaged here, but Girard’s biblical anthropology would help to fill out this picture.

In “Towards a Sacrificial Aneconomy? Georges Bataille and the Aporia of Sacrifice,” Marie Chabbert consult’s Jean-Luc Nancy’s critique of Bataille’s sinister flirtation with sacrificial violence, a disarming wedding of Eros with Thanatos, which is etherealized after WW II. As a matter of fact not cited here, a romance with nonsense, such as Dadaism and Surrealism, issued from the horrific violence of WW I, as French thinkers experienced widespread disillusionment with Western institutions and the shibboleths of bourgeois humanism. The Holocaust, she notes, changed the way to think about all this; rather than a black hole in history, it stands as an end point, the dark mirror of long-term institutional practices coming home to roost. This is Jean-Luc Nancy’s take on it, as available in the words one of his commentators, whom she quotes as follows: “The limit of the thought of sacrifice, its historical limit… is the experience of the death camps, which is perhaps the ultimate horizon of the whole of the modern thinking of sacrifice” (30). Chabbert follows both Blanchot and Nancy in advising us to step away from the worst of Bataille’s lucubrations, while aligning with Derrida’s reading of Bataille. The target here, of course, is metaphysical closure, with aporia as their end point, though it may strike readers as the counsel of despair: “Derrida’s deconstructive strategy emphasizes and maintains the aporetic structure identified in supposedly absolute concepts and unified theories” (38). No wonder that Girard does not appear in these pages (nor anywhere in Derrida’s own writings), for his mimetic hypothesis does accumulate to a unified theory, which repels as many thinkers as it attracts. Chabbert would certainly be among the former. When she embarks on political implications, introducing John Milbank and Jean-Luc Marion into the discussion, we are invited to consider “the imperfection of politics” (40), along with “an uncontaminable openness to change” (40), a phrase lifted from yet another scholar. This harmonizes with van der Walt’s conception, along, I suspect, with most reasonable people, though not in so many words, and so many, many dense formulations, tongue-twisting neologisms, and cumbersome bibliographies. (This kind of writing in several of these essays makes for unnecessarily difficult reading, spawned by acolytes of “French Theory” whose sell-by date should have expired by now.) Democratic institutions and constitutions are by definition dedicated to self-critical renewal, not unlike biblical inspiration. Not unlike Pascal’s wager for faith in eternal salvation, democracy in a desacralized, disenchanted world comes down to a “beau risque à courir.” It’s not a sure bet in our fraught political climate, marked as it is by neofascist clamor, that informs the concerns of a number of these essayists.

Brian W. Nail’s “Homo Sacrificus: Sacrificial Economization and Neoliberal Subjectivity” enlists the rival and complementary anthropologies of Girard and Walter Burkert, whose Homo Necans added yet another modifier to our species’ definition. They are taken on board here “to demystify the violence inherent to the logic of neoliberalism” (79); by this he means a competition-based theory of society that is dominated by “the ideological and institutional symbiosis between states and the industry of global finance” (80) that functions to the benefit of corporate shareholders and that, in his view, has colonized all domains of human subjectivity. The result is “wasted lives,” victims of the “neoliberal security state”; the culprits are, Nail quoting Kimball here, “stratified social institutions that funnel resources up a narrow hierarchy of privilege and power” (88). In the global empire of finance capitalism, depersonalized alibis for agency—terms of trade, market demands, competitive pressures, productivity, efficiency—remove the human factor in the harvests of precarity, when everything is weighed in terms of creditor/debtor relations. A surplus population of “flawed consumers may be regarded as collateral damage of economic progress” (81) due to what Harvey Cox, quoted herein, calls a “market theology” (88). And an imperial corporatocracy “mystifies its own sacrificial logic through rhetorical appeals to the common project of economic nationalism” (94).

Girard himself has concisely pilloried our frantic consumerism in Battling to the End, and Nail’s account can be said to fill out that critical view with multiple references to economic theorists, the bestselling Thomas Picketty, Michael Lewis, and Karl Polanyi among them. Where archaic cultures sacralized violence, socioeconomic stratification and consequent immiseration wrought by capitalism are naturalized, which comes to the same pseudo-foundational thinking. Nail’s solution calls for “social and political cooperation” that is “not exclusively based upon ideological commonality but rather ontobiological mutuality” (97), the goal being “a renewal of the demos and a restoration of communal forms of the social good that are insulated from the corrosive influence of financiarization” (98.) This, after having elaborately argued that nothing is insulated from the systemic, tentacular reach of the corporatocracy. His final remarks return us to “the primordial figure of homo sacrificus (98) with Derrida’s meditation of the Akedah (Van Der Walt goes there too) in The Gift of Death, where he reflects on the possible/impossible range of responsibility: “I put to death, I betray, and lie, I don’t need to raise my knife over my son on Mount Moriah for that. Day and night, at every instant, on all of the Mount Moriahs of the world, I am doing that, raising my knife over what I love and must love, over the other, to this or than other to whom I owe an absolute fidelity, incommensurably” (99). I find that these words resonate with the elder Zosima’s profession of faith in Brothers Karamazov: “Each of us is guilty in everything before everyone, and I most of all.” As we reasonably expect, a truism comes to light: Great minds—Girard, Derrida, Dostoyevsky, for example—think alike.

Awakening: Exploring Spirituality,

Emergent Creativity, and Reconciliation

Timothy Reynolds

Edited by Vern Neufeld Redekop and Gloria Neufeld Redekop

Edited by Vern Neufeld Redekop and Gloria Neufeld Redekop

Lexington Books, 2020

361 pages

Vern and Gloria Neufeld Redekop, in Awakenings, offer to the mimetic theory conversation started by René Girard a companion that will serve to spark conversation about the work of reconciliation.

Both of these editors have published works pertaining to conflict and reconciliation, and here they have brought together scholars whose expertise ranges from theology to literature, conflict to compassionate listening, and psychology to emergent creativity. In less than 400 pages, the writers have managed to pique many interests and raise many questions for creating communities where reconciliation can take place.

While not a book about Girard per se, nor directly related to the mimetic theory for which he is famous, those acquainted with as well as those formed by Girard’s theory will find this work of interest. In fact, this volume could be considered a “next step” for those studying Girard—those who may have found themselves asking, “So Girard identified violence at the foundation of society, now what?”

Whereas Girard’s work focuses on violence bought on through mimesis—and only quelled by the identification and killing of a scapegoat—this volume looks at peaceful reconciliation. Drawing heavily on the work of American biologist/medical doctor Stuart Kauffman on complex systems, this book helps readers understand how reconciliation often emerges from chaotic systems, and even in unexpected ways.

In the first section, about “Science, Emotions, and Re-enchantment,” Kauffman looks at the “re-enchantment of humanity.” He posits, via Max Weber, that the dis-enchantment of humanity began with Isaac Newton and continues into the present. Kauffman says from the beginning of his chapter, “I am advancing the hypothesis that in the biosphere we do not know and we cannot know what will happen, that is, the future cannot be pre-determined” (20). In good, scientific fashion, he then goes on to offer three corollaries that follow from the assumption: (a) the world in which humanity lives is full of “creative” possibilities; (b) “the creative emergence of something new establishes something with its own ontology” (this something cannot be reduced to physics nor be determined by the laws of physics); and (c) “our minds can make a difference to what happens in the world” (20).

Kauffman’s approach throws any given situation of conflict at the mercy of all the players involved. Each of the writers then follows with their own understanding of the process of reconciliation, but a main theme that arises is that, at its foundation, reconciliation is bound to the mercy of listening, speaking, and allowing the eventual outcome to emerge—whatever that outcome might be.