In this issue: looking forward to the meeting in Paris, an interview with James Alison, remembering Girard in video interviews, a report from the Dutch Girard Society, and more news and events.

Contents

Letter from the President: Martha Reineke, Rendezvous in Paris

Editor’s Column: Curtis Gruenler, The Joy of Relationality

COV&R Annual Meeting, Paris, France, June 14-17

Girardian Intersections, Online, August 19, 2023

Theology & Peace Annual Gathering, Chicago, IL, October 5-8, 2023

Be Not Conformed: René Girard at 100, Washington, DC, November 3, 2023

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion, San Antonio, TX, November 18-21, 2023

Event Report: Marina Ludwigs, Mimesis Scandinavis

Interview: Erik Buys, James Alison: “God is not a celestial Kim Jong-un”

Program Notes: John Babak Ebrahimian, Remembering Professor René Girard: A Tribute

Gabriel Gutiérrez Javán, Tiempos Miméticos by Jorge Márquez Muñoz

Letter From the President

Rendezvous in Paris

Martha Reineke

In just a few weeks, from June 14 to 17, we will be gathering at the Catholic Institute of Paris (ICP) for our annual meeting, where we will be graciously hosted by Professor Camille Riquier, Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy at the Institute. Founded in 1875, the Catholic Institute of Paris is the inheritor of the medieval liberal arts colleges and lies in the tradition of the Sorbonne, the oldest academic institution in France. We are deeply honored to be in partnership with such a prestigious university in Paris, which previously honored René Girard by conferring on him the 2009 Doctor Honoris Causa. We are grateful to have received this invitation from Dean Riquier after the war in Ukraine necessitated that we no longer meet as originally planned in Romania.

We will be partnering for the annual meeting with the Association Recherches Mimétiques. Emmanuelle Chantre and Paul Dumouchel have been working tirelessly on the on-site logistics of the conference. With registration for the conference nearly complete and the conference schedule finalized, I am delighted to tell you that the meeting will be the largest in the history of COV&R annual meetings. We have over 150 registrants, with further registrations expected  between now and the first day of the conference. Moreover, the conference will feature the most extensive international representation in the history of COV&R annual meetings. Every continent except Antarctica will be represented among our attendees; at the moment, we have registered scholars from twenty-seven countries. Attendance will mirror in its geographical expanse mimetic theory’s breadth of influence around the world.

between now and the first day of the conference. Moreover, the conference will feature the most extensive international representation in the history of COV&R annual meetings. Every continent except Antarctica will be represented among our attendees; at the moment, we have registered scholars from twenty-seven countries. Attendance will mirror in its geographical expanse mimetic theory’s breadth of influence around the world.

We are so very appreciative of all the means that ICP is so generously putting at our disposal to make the partnership of COV&R, ARM, and ICP on this auspicious occasion an unqualified success.

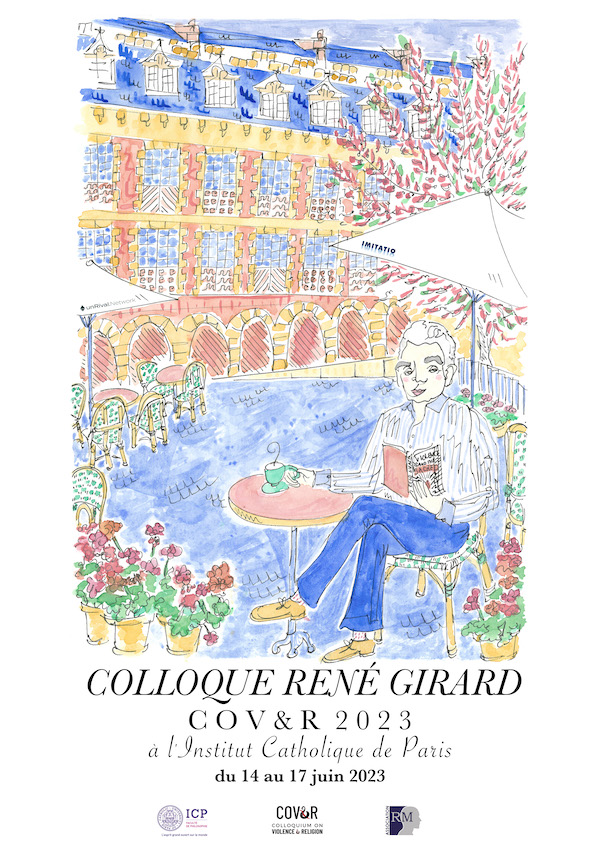

I am delighted to announce that, in celebration of this wonderful occasion, a commemorative poster featured here has been created by the talented Paris-based artist Celia Marie Petersen. Conference registrants will be able to purchase it now and pick it up at the conference.

I look forward to meeting many of you in Paris!

Editor’s Column

The Joy of Relationality

Curtis Gruenler

What I enjoy most about editing this Bulletin is how it keeps me in touch with people in the COV&R community. We not only share an interest, but that interest is one that we find to be a key to understanding human relationality itself. Further, we find it a guide to more harmonious and fulfilling relationships. It is an especially congenial group. I feel fortunate to occupy a position that comes with a routine for keeping up with people.

Central to COV&R’s relational life since its inception has been its annual meeting. This year, we have the special joy of meeting jointly with the Association Recherches Mimétiques, to which we are deeply grateful for hosting our meeting in Paris. From where I sit, it has seemed that the French-speaking and English-speaking mimetic theory communities have operated on separate tracks, so I am excited for our paths to cross. (If anyone would be interested in the possible collaborative writing project on mimetic theory and literary theory I discussed in my previous column, please let me know. I would love to talk to you in Paris!)

While there are abundant signs of interest in mimetic theory outside of academia, most academic disciplines remain, for a host of reasons, resistant to it. Those of us committed to academic work need each other for intellectual friendship, yet few of us can afford to make COV&R our primary academic guild because our disciplines oblige us to membership in a more mainstream disciplinary associations. Meanwhile, COV&R remains committed to including what we have tended to call “practitioners,” who make up an increasing proportion of our membership. In an ever-changing media landscape, while facing the climate crisis and sorting out what has changed after the COVID-19 pandemic, we are looking for new ways to connect while keeping up the routines of meetings and publications that have served us well. I look forward to conversations in Paris about the future of mimetic theory and the mimetic theory community.

My greatest pleasure as editor has been working with Matthew Packer, who has served as book review editor since I started in 2016. By my count, that makes 92 reviews he has solicited and edited. Matt will be very reluctantly stepping away from his editorial role after this issue, though he will remain a member of the COV&R board. Thanks, Matt!

As the volume of books engaging with mimetic theory and worthy of attention from mimetic theorists has grown, so has the task of arranging for reviews. We could like to try appointing several book review editors, with areas of responsibility organized by language and, perhaps secondarily, by academic discipline. For those in academic positions with service expectations, being a book review editor would be something to include on a c.v. If anyone would like to inquire about being involved in COV&R in this way, or would like to nominate someone as a possible candidate, please let me know. Or talk to me in Paris!

News

A 20% discount is now available to COV&R members for the two most recent volumes in Michigan State University Press’s series Violence, Mimesis & Culture: Alterity by Jean-Michel Oughourlian, translated by Andrew McKenna, and Violence and the Oedipal Unconscious, volume 1: The Catharsis Hypothesis by Nidesh Lawtoo. Three volumes published in 2022 also qualify for the 20% discount: The Time Has Grown Short: René Girard, or the Last Law by Benoît Chantre, translated by Trevor Cribben Merrill; Toward an Islamic Theology of Nonviolence: In Dialogue with René Girard by Adnane Mokrani; and Jean-Pierre Dupuy’s How to Think about Catastrophe: Toward a Theory of Enlightened Doomsaying. In addition, a 30% discount is available on selected titles from the backlist with a purchase of three or more. For more information, please see this page in the members section of the COV&R website. The same page includes a discount code for ordering through Eurospan, which has better shipping rates when ordering from Europe than ordering directly through MSUP.

Michigan State University Press has also announced two new Studies in Violence, Mimesis & Culture titles due out later this year: Mimetic Theory and Its Shadow: Girard, Milbank, and Ontological Violence by Scott Cowdell and Violence and the Mimetic Unconscious, volume 2: The Affective Hypothesis by Nidesh Lawtoo.

The Mimesis collection published by Universidad Francisco de Vitoria has announced its first book: Acabar a Clausewitz. Conversations with Benoît Chantre, a Spanish translation of the last work written by René Girard, with a preface by Benoît Chantre and some final reflections by René Girard himself, which appeared for the first time in the expanded and enriched French edition published by Grasset in November 2022. This volume will be followed by a series of titles: (Neo)Fascismo: contagio, comunidad, mito by Nidesh Lawtoo; Dostoievski: del doble a la unidad, the only work by René Girard not yet translated into Spanish; Voces desde la oscuridad. Goya, Büchner, Verga, Weil, Kafka, by Giuseppe Fornari; and Crítica girardiana a la teoría de Girard. Un homenaje, by Cesáreo Bandera.

In November, the seminar organized annually by the research group in mimetic theory based at the University Francisco de Vitoria, Violencia y Sociedad, will celebrate the centenary of the birth of René Girard, “continuing the celebrations that will begin with the annual meeting of COV&R,” writes organizer David Garcia-Ramos Gallego. “The seminar will be dedicated to exploring the voices of the new victims, thus expanding the understanding of the victim as a central phenomenon of mimetic theory and of the texts that today’s victims produce—texts that must be reconstructed and thought from the silence, manipulation, disinformation, and cultures of cancellation, political correctness, new radicalizations, neo-fascisms, populisms, and other isms that spread through social networks and new languages.” For more information, contact David or Blanca Millán.

Submissions are due 1 June 2023 for an issue of Revista Interdisciplinar De Teoría Mimética. Xiphias Gladius on the theme “New radicalities, new victims. Approaching the current phenomena of radicalization.” See the call for papers.

The website Syndicate is running an online symposium on Brian Robinette’s outstanding new book The Difference Nothing Makes: Creation, Christ, Contemplation. Contributors include some names familiar to COV&R: Scott Cowdell, S. Mark Heim, Chelsea King, and James Alison. Brian also spoke about the book recently at the quarterly speaker series sponsored by Theology & Peace; a recording is available on their YouTube channel.

Thanks to Berry Vorstenbosch for his report on the recent history of the Dutch Girard Society below. An article by a member of this group, Els Launspach, is newly published on our member articles page: “Reading Shakespeare’s King Richard III against the Grain.”

Lastly, from a link posted to the Facebook group “René Girard’s Mimetic Theory”: 34 podcasts about Girard and mimetic theory.

Forthcoming Events

COV&R Annual Meeting

Partnering with Association Recherches Mimétiques

The Catholic Institute of Paris

June 14-17, 2023

A Celebration of René Girard’s 100th Birthday:

The Future of Mimetic Theory

Full information, including plenary speakers, schedule, and accommodations is available here. The registration page is here.

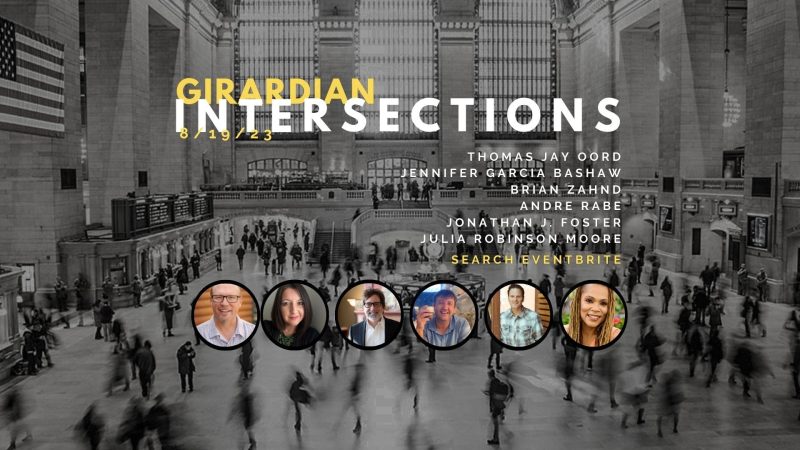

Girardian Intersections

Online

August 19, 2023

Four hours of Girardian goodness sponsored by Center for Open and Relational Theology with scholars and artists like––

- Jonathan J. Foster, author of Theology of Consent: Mimetic Theory in an Open and Relational Universe, introducing mimetic theory.

- Julia Robinson Moore, professor and founder of The Equity in Memory and Memorial Project, speaking at the intersection of Girard and the Af/Am experience.

- Brian Zahnd, best-selling author, and pastor giving insight at the intersection of Girard and the Church.

- Andre Rabe, author and founder of the Mimesis Academy speaking about his doctoral dissertation which lives at the intersection of Girard and the philosopher, Alfred North Whitehead.

- Jennifer Garcia Bashaw, from The Bible with Normal People, professor and author of Scapegoats: The Gospel through the Eyes of Victims, illuminating the intersection of Girard and the Bible.

The event is hosted by best-selling author and open and relational theologian Dr. Thomas Jay Oord.

Get in on the discounted early price of $19.99

Normal price of $29.99 kicks in 30 days from event start.

Theology & Peace Annual Gathering

Chicago, Illinois

October 5-8, 2023

Plenary speakers will be Adam Ericksen, pastor of Clackamas United Christian Church, OR, and Executive Director of The Raven Foundation, and Dr. Sharon Baker Putt, Professor of Theology at Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, and author most recently of A NonViolent Theology of Love: Peacefully Confessing the Apostle’s Creed. Dr. Putt presented ideas from her newest book at the Theology & Peace Quarterly Speaker Series on February 23, 2023. Click here to view her presentation.

The meeting will be held at the Casa Iskali Our Lady of Guadalupe Campus located outside of Chicago. For complete information and registration, see the Theology & Peace website.

Be Not Conformed: René Girard at 100

NOVITATE Conference

Catholic University of America, Washington, DC

November 3, 2023 (note new date)

The first NOVITATE gathering will host a full day of presentations, panels, and dialogue, concluding with a dinner banquet to honor Girard’s legacy. Abstract submissions, due June 30, are welcome from anyone who is interested in the work of Girard and how it relates to the theme, “Be Not Conformed.” Conference presenters will have their registration fee waived and may receive an additional stipend for speaking. Apply to attend here.

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion

San Antonio, Texas

November 18-21, 2023

Registration is open for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion and the Society for Biblical Literature. COV&R is sponsoring two sessions:

Session 1: “Policing, Disability, and Conversion: Mimetic Theory in Contemporary Conversation”

Saturday morning, 90 minutes, time and location TBD

- Lyle Enright (UnRival Network), “Archimedes and René Girard: Cultivating and Replicating Mimetic Theory’s ‘Eureka Moment’ through Conversion Stories”

- Susan McElcheran (University of St. Michael’s College, Toronto), “Philosophies of Intellectual Disability in Conversation with Mimetic Theory”

- Charles Bellinger (Brite Divinity School), “Mimetic Theory and the Training of Police Officers”

Session 2: “Roundtable Session on Brian Robinette’s The Difference Nothing Makes. Creation, Christ, Contemplation”

Sunday morning, 2 hours, time and location TBD

Presider: Grant Kaplan (Saint Louis University)

Roundtable Participants:

- John Betz (University of Notre Dame)

- Amy Maxey (Oblate School of Theology)

- Chris Haw (University of Scranton)

- Grant Kaplan (Saint Louis University)

- Brian Robinette (Boston College)

Business meeting to follow the conclusion of this session.

Event Report

Mimesis Scandinavis

Marina Ludwigs

The Girardian Society of Scandinavia, Mimesis Scandinavis, had its second annual conference on May 12-13, 2023. The conference took place in Stockholm, Sweden, on the campus of Stockholm University. The common theme of the conference was event in Girardian theory and the place of evental thinking within mimetic analysis. Nine participants, coming from Sweden, Norway, Finland, and the U.S., took part in the conference on the topics ranging from literature, to film, to performance, to religion, to city planning, and to a general elaboration of Girard’s theory through the prism of a recently published tome by Bernard Perret. All presentations generated lively discussions, and the conference was judged by the group to be successful based both on the quality of the contributions and variety of topics. The date and location of the next meeting has not yet been determined.

Here is a list of the presenters and their titles:

- Per Bjørnar Grande. “Girardian Theory in Relation to Religious Theory of the 20th century: Otto, Durkheim, Eliade, Berger”

- Anders Olsson. “Bernard Perret’s critical synthesis Violence des dieux, violence de l’homme. René Girard, notre contemporain (2023)”

- Klas A. M. Eriksson. “Modernism and Sacrifice in 20th century Stockholm – The Klara Neighboorhood as a Scapegoat for the Old World’s Urban Misery”

- William A Johnsen. “‘The Missing Mother’ and the Continuing Fecundity of René Girard”

- Hanna Mäkelä. “The Victim’s Voice is Heard: Race, Class, Gender, and the Sacrificial Crisis in Sarah Moss’s novel Ghost Wall”

- Alexandra Urakova. “A Gift with No Giver: The Narrative of Sacrifice in Maylis de Kerangal’s Mend the Living”

- Joakim Wrethed. “The Girardian Event and the Literary Event: The Scapegoat and Revelation in Alice Munro’s ‘Runaway’”

- Marina Ludwigs. “Mimetic Desire and the Event of Narrative Closure in 2022 film Aftersun”

- Charlotta Palmstierna Einarsson. “Difference and Creativity: The Role of Desire in Deleuze and Girard”

Interview

James Alison: “God is not a celestial Kim Jong-un”

Erik Buys

Editor’s note: This is the English original of an interview COV&R board member Erik Buys conducted and translated into Dutch for the April 5, 2023 edition of the weekly magazine Tertio. Thanks, Erik!

In Jesus, God makes himself known as a forgiving victim. That idea is central to the work of Roman Catholic priest and theologian James Alison. Among other things, it is the result of a thorough dialogue with the cultural theory of René Girard. In addition, the Brit is best known for his commitment to the LGBTQ+ community, to which he himself belongs.

In Jesus, God makes himself known as a forgiving victim. That idea is central to the work of Roman Catholic priest and theologian James Alison. Among other things, it is the result of a thorough dialogue with the cultural theory of René Girard. In addition, the Brit is best known for his commitment to the LGBTQ+ community, to which he himself belongs.

That James Alison’s books are deeply inspiring is not only evidenced by the enthusiastic recommendations of well-known readers such as Timothy Radcliffe, Richard Rohr, Monica Furlong, or Rowan Williams. The author is also constantly invited to give lectures and lead retreats. He rarely is in Madrid for a long time, where he currently lives. “I am traveling around the United States and am currently staying in the Minneapolis Jesuit community,” he clarified while video-calling Tertio. “The crucified one reveals himself as a forgiving love, through and beyond death,” emphasizes the gentle thinker.

Whoever says forgiveness also says sin. According to some, a sense of sin is at the root of guilt and shame with which the Church has kept people under wraps for centuries. What do you make of that statement?

That has certainly been the case too often. Usually we assume that we sin first and then receive the conditions for forgiveness: “If you repent, I will forgive you.” As a result, we end up in a world of emotional blackmail. That mentality is terrible. It turns God into a petulant tyrant. It makes faith a convenient tool for shaming people and controlling them.

And yet you see the doctrine of original sin as a source of joy in your book The Joy of Being Wrong. Why?

To understand that, you have to think forgiveness and sin in the right order. The essential Christian understanding is that forgiveness precedes repentance. You see that, for example, in the parable of the prodigal son. I prefer to call it the parable of the self-effacing father. When his youngest son reappears, clearly driven by opportunistic considerations, the father runs towards him in a most undignified manner. When the elder son turns up, he comes out to him like a servant, and begs his son to come in. At no point does he behave in a patriarchal manner. He does not disgrace his younger son. He sets no conditions for forgiving him. He does not magnify his possible feelings of shame. His other son, who remained at home, wants to do so. But shame would prevent the youngest son from acknowledging sincerely where he falls short. And then he does not get anywhere. The proper definition of sin is: that which can be forgiven. When we no longer have to be ashamed of one another, we can receive forgiveness and take responsibility for our actions, genuinely. Then we can grow. The teaching on original sin can be reformulated as the teaching on our capacity to be forgiven. It is, put another way, the teaching about our capacity to grow in who we are from the beginning and what we are called to. Thus, the capacity to be forgiven constitutes our access to the fullness of creation, to an existence that is much richer. The joyful news is that we have that capacity in common with each other. One human being has no more original sin than another (laughs).

So the awareness of sin is liberating, if understood properly?

If sin is what you can be forgiven for, an awareness of sinfulness is actually a relief. It is not frightening. You are not at the mercy of sin. In contrast, there are fixed laws and dynamics to which you may be subject, such as mental illness. You then have to learn to deal with that. At worst, straitjackets and cages await. In contrast, the notion of sin suggests a flexibility in our process of becoming. We can always become more human. Saying “I am a sinner” should not be seen as a form of self-flagellation; rather it is the sign of being relaxed enough about being forgiven that I don’t need to justify myself. True forgiveness is not an accusation. When people are accused, they try to justify themselves. The danger is that they then shift the blame to others to defend themselves.

To understand the notion of sin as an accusation would be wrong?

That is a perversion, indeed. The Gospel leaves no doubt about that. A right understanding of sinfulness prevents you from judging others. On the contrary, you discover that you are like others in that respect. Designating someone as the bad guy who is radically different from you and a group of like-minded people, on the other hand, maintains an oppressive, even violent social structure of fear and shame.

We are constantly in danger of getting stuck in violent structures. What role does Jesus of Nazareth play in our liberation from those?

Let me explain that with an analogy. Imagine what it’s like sometimes in high schools. A group unites against a misfit, a certain Fernando. I tell his story, by the way, in the book series Jesus the Forgiving Victim. Several students make Fernando feel that he does not belong, for whatever obtuse reason. In their eyes, perhaps he wears the wrong clothes, or he is not rich enough and so on. Some no doubt breathe a sigh of relief that they themselves are not the group’s piss-poor. Indeed, precisely because they fear that, they actively make fun of Fernando, while others relate to him with mostly indifference. No one wants to be on the spot of shame and embarrassment. And the best way to avoid that is to make sure that someone like Fernando occupies that spot in their place. To make a long story short: Fernando leaves school, but returns after six months. Imagine that he suddenly does wear the supposedly right clothes and turns out to be rich and powerful. Once again, the frightened will seek security, but this time by gaining favor with Fernando. They conveniently blame their past misbehavior toward him on the bad influence of one supposedly real bully (or a negligible group of bullies). By doing so, they are already reducing the risk of falling into the place of shame themselves. In their place, someone has to pay who represents evil. So they play the violent game they have always played: the group unites against one (small group) who is considered radically different.

The Gospel offers another possible scenario. In its light, Fernando returns as he has always been, but clearly without seeking revenge or providing moralistic criticism. On the contrary, he forgives his fellow students because he actually likes them. He knows that in reality they are quite nice and actually have a lot going for them. So the fearful no longer have to hunt for yet another victim to occupy the place of shame in their place. They no longer have to shift responsibility for their behavior onto someone else. They can learn to be together in a different, nonviolent way and discover that as a surprising aspect of themselves. Jesus works something similar, but on a general human level. He invites us to play a game governed not by fear and shame, but by mutual forgiveness.

Sometimes we say that others should be ashamed of themselves. You claim that Jesus occupies the place of shame voluntarily. Does God play the game of shame and disgrace as well?

Not at all! God is not a celestial Kim Jong-un who needs masses of militarized people to stroke his ego and who will cut your head off if you refuse to do so. Our world produces those kinds of leaders. When Jesus is crucified, he satisfies a human propensity for violence. He does not satisfy divine wrath or anything like that, which does not exist anyway. Jesus embodies the generosity of God, even when man shows his worst side.

Nevertheless, that generosity is destroyed by death?

No, Jesus even makes death a sign of that generosity. He does not allow himself to be blackmailed by a fear of violence and death. That allows him to occupy the place of shame without being controlled by it. He does not answer violence with violence, even unto death, which constitutes a love that prevents people from being victims of violence. The resurrection of the crucified Jesus is contained in his forgiving presence. That presence invites us to become partakers of a love that is in no way fascinated by suffering and death. It opens the way for a life that no longer depends on death.

What does that life look like?

It enables you, for example, to stand up for justice non-violently, without worrying about the possible negative consequences of that for your reputation, or even your life. A quote from the first letter of John formulates that condition well: “We have passed from death to life; we know it, because we love our brothers. Man without love is still in the realm of death” (1 Jn 3:14).

I cannot emphasize enough that our lives are more in need of deliverance from shame than from sin. Shame drives us much more strongly than the things for which we can take responsibility. Dealing with shame is much more important than dealing with sin. And that can only be done by someone who is affectionate to us, someone who is very close to us and respects our fears. You need someone who respects the delicate nature of where we are, and who does not bring us more shame. By occupying the place of shame, that person can hold us tenderly and allow us to let go of our shame. The place of shame is the place no one wants to occupy themselves. It is the place we avoid by conspiring with others against someone who is put there in our place. But when it is occupied by someone who is affectionate to us, we no longer have to play that game of collusion. Remember the story of Fernando, which we were talking about a moment ago. He loves and forgives his fellow students instead of taking revenge. As a result, the former bullies don’t have to shift their responsibility to someone they can shame. The father in the parable of the prodigal son, who is actually disgraced by his two sons, also acts like Fernando, and so does Jesus. Then an inclusive way of communicating with others who are disgraced becomes possible. From there, a new kind of community and a new kind of living together can grow.

Forgiving love breaks through the condition in which we are stuck because of shame. That is partly what is meant by resurrection. It means that the fear of losing things no longer dominates us. We may have to testify about an iniquity someone has suffered, and we will be at risk because of it. We won’t find that worthwhile if we are guided primarily by the fear of exclusion, violence and death. For the great and powerful will often win.

In today’s world of social media, some people supposedly stand up for justice, but it seems they use their actions to flaunt a good image.

Yes, in that case standing up for justice becomes a way to get revenge. Or to build a reputation. Virtue signaling, as it is called. If, on the other hand, you dwell in the generosity that is not defined by fear, you are willing to lose because you cannot actually lose. You are already held up in what is greater than any loss. When you have no fear of losing, you can do what love asks of you in any context. Then you feel no need to score in a cheap way, by virtue signaling or by revenge, or by appearing to be a winner. Then you can stand up for others, with the necessary risks, although of course you must not endanger your fellow human beings. And the more people do that, the more the frightening beast disappears that feeds on our fear and shame.

Do you have to know Jesus to live that kind of life?

The generosity that makes itself known in a special way in the life of Jesus is also at work elsewhere. Often we see that people know what that means without all the religious paraphernalia. Conversely, we find that the Jesus story is sometimes told and lived very poorly in supposedly Christian circles. I invariably look for the real thing, both inside and outside church walls, and try to find opportunities for imitation in that.

Would you ever step away from the Church?

All institutions are sacrificial. They sustain themselves by setting boundaries and thus organizing forms of exclusion. This does not mean that we should destroy institutions—which in itself is also sacrificial—because then you get other ones subject to the same logic. Those who create a supposedly pure group to distinguish themselves from a Church with scandals are already playing the game of shame again. And then sooner or later you fall back into forms of fear-mongering hypocrisy. The question is how to subvert the sacrificial excesses of an institution from within. The synodal process under the impetus of Pope Francis seeks to address that, among other things.

There is a dire need for forgiveness, even within the Church. What if you do not arrive at forgiveness?

Forgiveness can never be a demand, because then you get bogged down in a moralizing argument again. You don’t have to be ashamed if you can’t forgive (yet). Apart from that, we must not forget that by forgiving you are not so much doing the wrongdoers a favor, but primarily yourself. A process of forgiveness prevents your life from being controlled by the evil that is done to you. Sometimes we chew on evil, as if it feeds us. It then gives us an identity. Of course it is necessary to acknowledge someone as a survivor of sexual abuse, but for the person in question you may hope that such evil eventually becomes a detail in their biography. Forgiveness is a call to freedom: “Don’t let the people who don’t have your best interests at heart get you, don’t give them free rental space in your head.” Forgiveness is the opposite of a command that turns you into a doormat. A process of forgiveness frees you from the identity in which you were trapped. It invites you into the adventure of a life of greater joy. Think of the withdrawing father from the parable already mentioned. He rejoices over his reunited family and just wants to throw a party, without his one son being ashamed or his other being bitter.

An Easter feast?

Indeed! (laughs)

Program Notes

Remembering Professor René Girard: A Tribute

John Babak Ebrahimian

Editor’s note: This article accompanies a collection of 27 interviews conducted with people who knew René Girard over the course of his academic career.

Among artists, thinkers, and geniuses who I’ve met and worked with, no one has influenced and changed my life more than Professor René Girard. I knew about him when I was a teenager and lived in Paris. There I saw him on Bernard Pivot’s television program Apostrophes. Yet it took till the summer of 1992 when I made an appointment with his secretary, Margret Tompkins, to talk to him about his books, theory, and ideas.

Among artists, thinkers, and geniuses who I’ve met and worked with, no one has influenced and changed my life more than Professor René Girard. I knew about him when I was a teenager and lived in Paris. There I saw him on Bernard Pivot’s television program Apostrophes. Yet it took till the summer of 1992 when I made an appointment with his secretary, Margret Tompkins, to talk to him about his books, theory, and ideas.

We started off by talking about Shakespeare and theater, which naturally led to discussing life, art, literature, religion, and the state of the world. He always smiled, listened patiently, and answered honestly and often with a warm laughter. My interaction and encounter with him enabled me to ask him the most simple or complicated questions. He loved and welcomed challenges with either a direct look, or with a smile and warm laughter. That summer as we discussed life, literature, culture, his books and theory, I asked him directly: “Professor Girard, if you say God exists, then why did he let World War II take place?” That question led to summer-long discussions where we met over coffee or lunch at the University coffee house.

The summer of 1992 I became his student, friend, and teaching assistant shortly after. With time, I also got to know to know his wife, Martha, and his children, Martin, Daniel and Mary.

The encounter was a revolution. If my meeting and encounter with him changed me 180 degrees, I wanted to know how he impacted his other students, colleagues, and friends. I set out to discover this by asking five simple questions from all those who knew him and had worked with him. The collection of the interviews as it stands is a rich testament to Professor Girard both as a scholar as well as a genuine and gracious human being and individual. They begin with his early days at Johns Hopkins and SUNY Buffalo and move on to cover his years at Stanford University and COV&R.

This tribute project is now posted on this YouTube channel for those who are interested in Professor Girard, his life, his thought, and his legacy.

Letter from the Netherlands

Still Going Strong: The Dutch Girard Society, 2009-2023

Berry Vorstenbosch

“It is remarkable that the group, which currently has only about forty people on its mailing list, has held together all these years.” These words were written by James G. Williams in his book Girardians: The Colloquium on Violence and Religion, 1990-2010. We find them in his introductory portrait of the Dutch Girard Society, who organized the 2007 COV&R conference in Holland. So, Williams’s observation was made more than ten years ago. And yes, we are still holding together, we are still thriving. Our mailing list has expanded to 62 addressees, which is still a very small number.

Here I want to give an update from the year 2009, which is about the time I joined the group, and which is also the year when we, with the help of a grant from Imitatio, registered as Stichting Girard Studiekring (Foundation Girard Study Circle). By then the circle was already twenty-eight years in existence, and those interested in our history can read more about it in Williams’s book.

Describing the group Williams continues: “Those who attend come from all over Holland, so the dedication for meeting and fellowship for learning is strong.” Here I must add that we have welcomed a number of Belgian participants. Also, Williams’s description of the meetings still holds: “When I asked a number of them what held the Circle together for so many years, their unanimous response was that the discussions were very interdisciplinary, in keeping of course with being followers of Girard and the mimetic theory. The meetings are casual and relaxed, and persons of widely varying backgrounds feel free to enter into the conversation.”

A part of the procedure is giving a turn to every visitor for commenting on the text that has been read or the passage being studied. This “ritual,” devised in the past by Michael Elias, and being already firmly in place when I joined the group, is very helpful in preventing the mimetic turmoil that so often arises in the arenas of free discussions.

Though the number of meetings each year (five) has remained constant in these years, we did have our worries about attendance. Neither the fear of implosion, nor the hope for expansion, proved to be justified. We are still going strong, with ups and downs, with people only visiting our group once or a couple of times and other people staying around. At the moment, our meetings usually are attended by some fifteen people. This is also the place to commemorate the two members who have frequently visited the COV&R conference: André Lascaris and Sonja Pos.

Once having become an official organization, our first chairman was Michael Elias, who had been a convener for some fifteen years by then. In this role he was later followed by Rob Gast. Other people who have been members of the “board” or organizing committee are Thérèse Onderdenwijngaard, Simon Simonse, and Els Launspach. At present we have Hans Weigand as our chairman, Hubert Darthenay as the treasurer, Jannet Delver as a board member, and I am the secretary, also taking care of the website.

Here I also must mention Joost Dancet, who has been of great help in giving our own website a facelift, and who is also the writer of many articles on mimetic theory and poetry on the website Poezieleesgroup De Reyghere.

In the past fourteen years we have organized a lot of events aside from our five-time-a-year gatherings. To begin with, in 2010 and 2012, also with the support of Imitatio, Thérèse Onderdenwijngaard twice organized a Summer School in mimetic theory at the ISVW (International School for Philosophy) in Leusden. Certainly, a number of Bulletin readers will have memories, either as a teacher or as a participant, of these summer events.

Another initiative we are proud to mention is the starting up of the Girard Lectures in the Netherlands, originally scheduled for once every two years. We now can look back on four lectures in total, given by Hans Achterhuis (2014), Willem Jan Otten (2016), Johan Graafland (2018) and Marcel Poorthuis (2020), some of them being quite well-known in cultural life in Holland. Also, we have organized a number of meetings with other study groups in Holland—one dealing with the work of Emmanuel Levinas, another with the work of Eugen Rosenstock-Hussey.

Then, between 2010 and the present day, we have organized two jubilee festivities for our 30th and 40th anniversary. I already mentioned that the true founding year was 1981, so yes, we are way older than COV&R 😉! At the jubilee in 2011 we presented the book Rond de Crisis, a collection of still valuable essays about mimetic theory in Dutch, edited by Michael Elias and André Lascaris and written by the members themselves. Together with Nico Keizer de book was presented in the Balie theater in Amsterdam.

This same theater was the place of our jubilee ten years later. This time we opted for a film fragment festival entitled Violence and Desire in Film, which was also broadcasted as a live stream. In this program Joachim Duyndam discussed a number of film fragments with Arnon Grunberg, one of the best-known novelists and columnists in the Netherlands. Due to copyright permission, the recording of this program cannot be put online, but if you are interested, we can send you a private link.

The period of the coronavirus lockdowns forced us to use and further discover the possibilities of digital meetings. Initially, being confined at home during the lockdown, we met at a higher frequency than we used to, with our Belgian members Erik Buys and Joost Dancet joining in, as well as Simon Simonse from Nairobi. Also, we had a number of sessions in English on the work of and attended by Per Grande, Julia Robinson Moore, Mark Anspach, and Wolfgang Palaver. These sessions were appreciated very much by our members, and we hope to continue scheduling new international meetings in the future.

Then, last year, Hans Weigand, assisted by our French member Hubert Darthenay, created a new translation of Girard’s first book—I will give the title in Dutch—De romantische leugen en de romaneske waarheid. Already in 1986 Hans created a translation of this book, then also assisted by Hubert. At present I am working on a translation of Nidesh Lawtoo’s (New) Fascism: Contagion, Community, Myth for the same publisher, Uitgeverij Noordboek. This publisher is seriously interested in mimetic theory, so the possibility exists that more translations will follow in the future.

The 2023 COV&R conference in Paris now is really getting close. Daan Savert and Bart Leenman are two of our younger members, who will be visiting COV&R for the first time. Bart Leenman will offer a presentation on Giorgio Agamben, which already has had a try-out in one of our sessions. Thérèse Onderdenwijngaard will, together with Martha Reineke, participate in a session on Wolfgang Palaver’s Transforming the Sacred into Saintliness. Joachim Duyndam, Michael Elias, and I will offer a session on “Madness, Religion and Mimetic Theory.” As to psychosis, Michael Elias and I both are experiential experts and have recently written a book about our experiences: Michael Elias published an autobiographical novel Hanesteen (Alectorius) in 2020, and I published a more theoretical work De overtocht: Filosofische blik op een psychose (The Crossing: Philosophical View on a Psychosis) in 2021.

I will end by mentioning five members many COV&R conference visitors will know. First of all, there is Erik Buys, prolific writer of books, articles, and website pages, whose wonderful website Mimetic Margins now has migrated to Scapegoat Shadows. Then there is Simon Simonse, whose magnum opus Kings of Disaster has been presented several times in the past years. Furthermore, there is Els Launspach, who has done several projects on Shakespeare in the past years, one of them on a high school. Her work helps remind us that Girard was very much a student of literary texts. (Editor’s note: see her “Reading Shakespeare’s King Richard III against the Grain” on the member articles page.)

If there were awards for Girardian achievements, Hubert Darthenay—apart from making good chances for the award for the best-dressed Girardian—would stand out as the one who has virtually visited all COV&R conferences. Apart from his help in translations and his role as a treasurer, Hubert’s contributions to discussions are always remarkable, be it only for his in-depth knowledge of nuances in the French language.

And last but not least, I must mention Wiel Eggen, who has a tremendous erudition and was the first one to find out that Jean-Paul Sartre had written about René Girard. Being both anthropologist and theologian, Wiel’s interest lies in the field of philosophical history of the monotheistic religions—at present, with the war in Ukraine in the background, with a focus on the dialogue with the Orthodox Church. In the oncoming issue of Contagion, Wiel will present an article about his anthropological work in Central-African Republic in the early seventies.

A summary of almost fifteen years of activity will never be complete. As for our members, a larger list of regular visitors of our meetings can be found on our website.

Personally, I feel the sense of community has not profoundly changed since the days I joined the Dutch Girard Society. This sense of community is carried, not by religious uniformity, but a sense of truth. Though we have our mutual differences, we share the belief that in many ways mimetic theory is looking in the right direction.

If you want to know more about the Dutch Girard Society, if you want a link of the film fragment festival or if you have a suggestion for offering a presentation for our group, please send a mail to [email protected]. And you always can take a look on our website: www.girard.nl.

Book Review

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the Bulletin editor, Curtis Gruenler.

Tiempos Miméticos

I: De inicios del siglo XX a la II Guerra Mundial

II: De la II Guerra Mundial al desmembramiento de la URSS

Jorge Márquez Muñoz, coordinador

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2022

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2022

455 + 339 pages

Gabriel Gutiérrez Javán

Universidad del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico

Editor’s note: Thanks to James Alison for translating this review from Spanish. Both volumes are currently available online at these sites: volume I and volume II. For a review in Spanish of a previous book by Jorge Márquez Muñoz, Anatomía de la teoría mimética. Aportaciones a la filosofía política, see here.

A few months ago, UNAM published Tiempos Miméticos (“Mimetic Times”), a work edited by Dr. Jorge Márquez Muñoz. Márquez, a professor in the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences at UNAM, is the foremost Mexican authority in the field of mimetic theory, which is to say, the thought of René Girard that has inspired at one and the same time the neuroscientist discoverers of mirror neurons and Peter Thiel, one of Silicon Valley’s greatest thinkers and entrepreneurs, while also making an impact simultaneously in anthropology and theology, and both economic and political theory.

Márquez’s publications dealing with Mimetic Theory began more than fifteen years ago with Las Claves de la Gobernabilidad (“The Keys of Governability”). The two volumes of Tiempos Miméticos are his most recent and extensive work in this field. Of the articles in these volumes, about 75% were written by Márquez himself, with the rest contributed by his UNAM colleague Pablo González Ulloa and a team of students.

We are given the history of the 20th century analysed through the categories of mimetic theory—not the whole of the 20th century, but from the end of the First World War until the dismemberment of the Soviet Union. Given that the possible sources from which to narrate such a history are infinite, Márquez concentrates only on the vision of Paul Johnson. This seems a good choice for an analysis based on mimetic theory: first because Johnson was a historian of the first rank and a master for other great contemporary historians. And second because Johnson constructed his history of the 20th century with a huge amount of biographical data and strips naked the rivalries and mimetic inspirations of the great personalities of the time. Johnson narrates history by means of flesh-and-blood people, which is just what mimetic theory also seeks, fleeing as it does from great metaphysical theories. These it calls “romantic lies.”

The authors of Tiempos Miméticos conduct a Girardian reading of each of the long and beautiful chapters of Johnson’s Modern Times. It is as if each chapter were interpreting a Shakespeare play (which Girard does in Shakespeare: A Theater of Envy), but instead of Hamlet and Othello we get Hitler and Kennedy.

Readers of Tiempos Miméticos will find the work to be dense; but with a little patience, they will learn a great deal: the history of the terrible 20th century; how so many big decisions were taken; mimetic theory; and a series of critiques of the conspiratorial “Big Theories” which simplify reality.

Each chapter has as its title a modified version of the title of one of the works of Girard or others of his school. For example: “I saw Hitler fall like lightning” tells the story of the second half of the Second World War and alludes to Girard’s own I See Satan Fall like Lightning.

Furthermore, each chapter is in reality a stand-alone essay. We are given a combination of theory, history, abstraction, and human beings in action. Together they yield a tale well-told, even when it is recounting the worst atrocities. The quotations from Paul Johnson and those of the authors inspired by mimetic theory are naturally complementary. It would even seem, on occasion (and the authors of Tiempos Miméticos observe this), as though Johnson had prior knowledge of mimetic theory (though this was not, in fact, the case). For illustration, here is a quote which is, to my mind, brilliantly apropos:

Proust and Joyce, the two great harbingers and centre-of-gravity-shifters, had no place for each other in the Weltanschauung they inadvertently shared. They met in Paris on 18 May 1922, after the first night of Stravinsky’s Renard, at a party for Diaghilev and the cast, attended by the composer and his designer, Pablo Picasso. Proust, who had already insulted Stravinsky, unwisely gave Joyce a lift home in his taxi. The drunken Irishman assured him he had not read one syllable of his works and Proust, incensed, reciprocated the compliment, before driving on to the Ritz where he had an arrangement to be fed at any hour of the night.

Six months later he was dead, but not before he had been acclaimed as the literary interpreter of Einstein in an essay by the celebrated mathematician Camille Vettard. Joyce dismissed him, in Finnegans Wake, with a pun: ‘Frost bitte’ (p. 11).