Contents

Letter from the President, Martha Reineke

Musings from the Executive Secretary, Niki Wandinger

Editor’s Column, Curtis Gruenler

Pandemic and Apocalypse, James Alison

Writing an Afterword on Pandemics, Berry Vorstenbosch

Report on the 2020 COV&R Board Meeting, Martha Reineke and Nikolaus Wandinger

COV&R Sessions at the American Academy of Religion

Collaborators Conference, Susan Wright

Collaborators Conference, Suzanne Ross

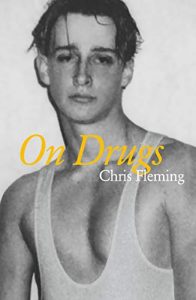

Chris Fleming, On Drugs, reviewed by Kathy Frost

Letter from the President

Forward Together

Martha Reineke

University of Northern Iowa

As I write, a number of universities across the US that opened for fall classes last week already have closed. Yet, even as the Dean of Students has informed me that two of my students are sick with COVID-19, face-to-face classes have begun at my university, which has picked as its motto for the fall semester “Forward Together.” To help pass the time during the first faculty meeting, a colleague shared with me a bingo card with amusing entries that captures the moment well. The center square contains a single word: “unprecedented.” Years from now, anyone reading this issue of the Bulletin will need only give it the briefest of glances to know it was written in the fall of 2020. Truly, we live in unprecedented times.

Although some entities and individuals are responding to our unparalleled circumstances by hitting the pause button, “Forward Together” very well captures the tone of July’s COV&R board meeting. We did postpone our annual meeting due to the coronavirus; nevertheless, in other respects, the Board is energized to make COV&R an even stronger organization in the year ahead. Augmenting our traditional channels, we want to position COV&R on digital platforms to offer mimetic theory as a vital resource for reflecting on world events and the social and cultural issues arising from them. The pandemic has made crystal clear that a digital environment in which mimetic theory can thrive is fast evolving and is highly unlikely to disappear after the pandemic ends. Board members shared confirming examples from our own lives: we teach and regularly host or attend meetings online; we have blogs; we record videos, put them on our YouTube channels, and share them; we contribute to and/or receive digital newsletters; we contribute to or host podcasts; we read daily digitalized articles from a number of popular and academic journals to which we subscribe. A number of us who are not digital natives have seen digitalization take hold in our daily lives only in recent years. Nevertheless, all of us agreed that the transformations we are experiencing are not transitory. Spurred on by the coronavirus, they are here to stay.

Yet, despite the breadth and variety of experiences we shared with each other during the Board meeting, we realized that, if any of us were to develop a communications strategy for COV&R, our personal experiences would not serve as reliable guides. Expertise is required in order to identify target audiences, create appropriate messaging, and best utilize communications platforms. A professional consultant will enable COV&R to explore options broadly and creatively, but also with knowledge and skills that will provide for a comprehensive strategy that has all the components we need to achieve our communication goals.

The Board meeting report offers details of an initiative to which the Board committed at our July meeting to hire a professional consultant to guide COV&R as an organization committed to sharing mimetic theory with a wide and varied audience. With a consultant’s help, we will position our membership to successfully meet communication challenges and opportunities of our time.

I am especially excited by the potential in this initiative to attract new members to COV&R. A number of small scholarly organizations similar to ours are struggling with declining membership. Members who retire from the profession are not being replaced by a younger cohort. In some cases, the downsizing of higher education—colleges and seminaries are closing in the US and contingent (non-tenure/tenure track) faculty now hold 70% of US university teaching positions—accounts for the loss of members. But a factor also seems to be that these organizations have no digital presence, not even websites. By positioning COV&R for a robust digital presence, not only will we be meeting young Girardians or potential Girardians where they hang out but also, and even more important, COV&R will be more inclusive of practitioners of mimetic theory whose areas of formal employment increasingly are located outside the academy. As a consequence of this initiative, mimetic theory will be more able to contribute to enhanced understandings of social and cultural issues with which individuals, communities, and nations are grappling. Mimetic theory is up to this challenge and, thanks to the Board’s forward-looking vision, so also is COV&R. The Board looks forward to sharing updates on this initiative with the membership at our 2021 meeting at Purdue University.

Musings from the Executive Secretary

Positive Models

Niki Wandinger

University of Innsbruck

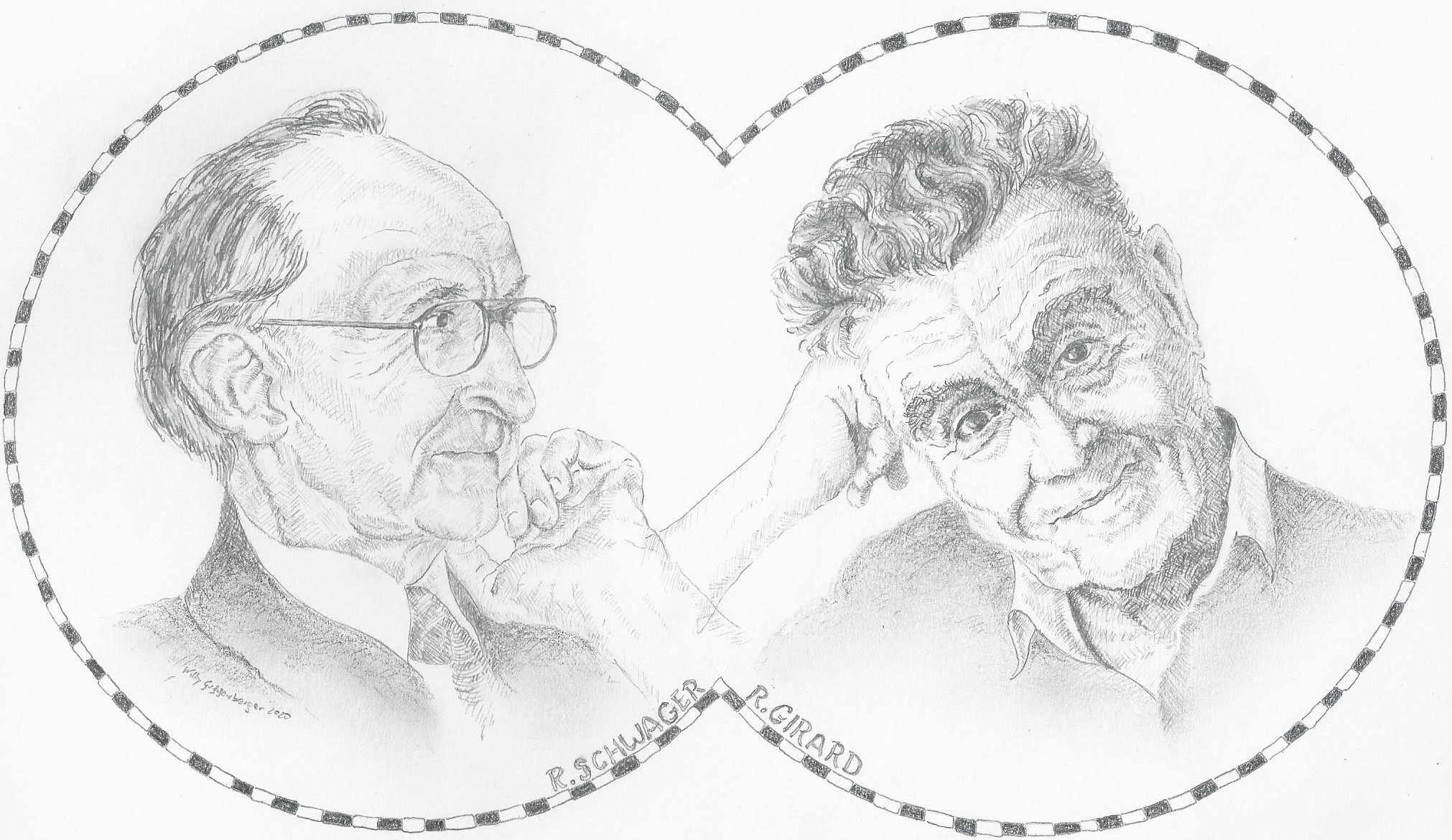

When one of last year’s winners of the Raymund Schwager Memorial Award asked whether there was a certificate in addition to the prize money, we realized that there wasn’t. But we thought there should be. Then the everyday hassles of our academic lives and later the Covid-19 crisis postponed all efforts to design such a certificate. At our online Board Meeting in July, however, we agreed that Maura Junius would design such a certificate. She suggested that a picture of Raymund Schwager, after whom the award is named, could be an element of the certificate. I thought a picture showing Schwager and René Girard together would be nice. When I later talked to my Innsbruck colleagues Wolfgang Palaver and Willy Guggenberger, telling them that I was searching for such a photo, Wolfgang came up with another idea: Why not have a drawing instead of a photo? And he knew where to get it, too. Willy Guggenberger had shown his talent for pencil drawings on many earlier occasions, and he agreed to devote some of his vacation time to create such a drawing. I received it a couple of days ago, and Martha Reineke, Maura, Wolfgang, and I were all quite happy with it.

The overall design of the certificate has not yet been completed, but Willy’s sketch will certainly be an element of the certificate, and the 2019 award winners will be the first to receive it, once the design has been completed. Clearly, Willy has taken two well-known photographs of the two thinkers as models, but he arranged them in his own way, and I think this arrangement does convey a special message about Raymund Schwager’s and René Girard’s relationship.

Raymund is looking at René, while René is looking at the viewers, at us. So, there is a triangulation, but I am not so sure whether the roles of subject, object, and model are clearly distributed. One could argue Schwager is the mediator here because he looks at Girard and directs our gaze – and our desire – also towards him. Yet, Girard looks at us. So, are we his desired objects, whose interest and attention he craves? And in a way, our gaze then wanders back to Schwager, as if to ask: Why is he so interested in the other guy? So, here what seemed to be the model becomes the object of our curiosity, and thereby of our desire. However, one thing is certain: The two are not in a mimetic rivalry. Neither do they stare off against each other, nor do they compete for our attention. In fact, it even seems to me that while Schwager does look at Girard, and Girard does look at us, both also look beyond this immediate focus of their gaze.

And this reminded me of one of the more remarkable passages quite early in their correspondence. In the summer of 1976, Schwager concluded a letter to Girard: “Permit me to finish with a very personal remark: I thank God in my prayers that he has given you this wisdom. At the same time this prayer is ‘the means’ for me to avoid falling into an absurd [literally: ridiculous] rivalry by taking you as model (master of thought).” (René Girard and Raymund Schwager. Correspondence 1974-1991. Translated by Chris Fleming and Sheelah Treflé Hidden. Edited by Scott Cowdell, Chris Fleming, Joel Hodge, and Mathias Moosbrugger. Violence, Desire, and the Sacred 4. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016, p. 33.)

After Schwager passed away, René Girard remarked that Schwager had been the only person who had really made him doubt his theory. Gasps of astonishment in the room! Then the explanation: because he (Schwager) was completely free of rivalrous envy. Schwager’s remark in his letter proves that this did not come just naturally to him. It grew out of his faith life and his trust in the power of prayer. René Girard also trusted in that power and he also avoided rivalry with Schwager. While faith and prayer are not everyone’s means, Willy Guggenberger’s sketch translates what it meant for the friendship of Raymund and René: It meant looking beyond the immediate focus of attention while not losing that focus.

Of course, these are my musings on the drawing, and you might have different ones or none at all. What I want to say for me: If we use Willy’s sketch to adorn the Raymund Schwager Memorial Award, I think we also state that we as a group are willing to live up to that heritage of looking beyond the immediate concerns, of avoiding rivalry by acknowledging the wisdom of the other person. I hope that we succeed.

Editor’s Column

Bob Dylan, Hypermimetic

Curtis Gruenler

Hope College

I’m especially grateful to James Alison and Berry Vorstenbosch for their reflections on the Covid-19 pandemic in this issue. As they both suggest, we are far from finished understanding this collective experience that is at once so familiarly mimetic and also, as Martie Reineke writes in her presidential letter, unprecedented. We welcome further reflections for the November issue (deadline: October 30) and beyond.

Another voice I have appreciate during the pandemic has been Bob Dylan’s, especially on his brilliant new album, Rough and Rowdy Ways. At 79, the great poet of our time is still giving. His songs have always been full of what James Alison calls the intelligence of the victim, nurtured by the folk and blues traditions in which he steeped himself, but flowing ultimately from the Bible. “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” from 1966 was never really about drugs: “Well, they’ll stone ya when… Everybody must get stoned.” The new album pulls the many phases of his career together like never before in what might, alas, be a final artistic statement. As he sings in “Mother of Muses,” a song about the Holy Spirit under various guises, “I’ve already outlived my life by far.” His voice has changed, even from his previous album of original songs, 2012’s Tempest (also a remarkably spiritual album). He sounds both mellower and more penetrating, deeper and more intimate, urgent but echoing with the depths of time.

I could go on and on, but the songs are to be heard more than analyzed. Still, here are some teasers for mimetic readings. “Murder Most Foul,” the 17-minute track about the death of President Kennedy, suggests its sacrificial dimensions and how they are answered by art. “Black Rider” compassionately diagnoses rivalry, scandal, and the satanic. “Crossing the Rubicon” might be about, among other things, and as its title suggests, Christianity and power. The opening track, “I Contain Multitudes,” recognizes the hypermimetic nature of great artists, like Walt Whitman, from whom the title quotes, but I don’t think he means to say that poets are all that special. His art just helps us see how we all contain multitudes.

“False Prophet,” my favorite track, addresses the mantle Dylan has wrestled with his entire career. It might be responding to a comment by Pope Benedict XVI, as discussed by Randy Coleman-Riese on the Cornerstone Forum blog. The song’s refrain rings changes on what it means to bear witness: “I ain’t no false prophet / I just know what I know / I go where only the lonely can go.” He turns the reference to a song by Roy Orbison (an old pal from the Traveling Wilburys) into solidarity with all manner of solitary suffering. Second time: “I ain’t no false prophet / I just said what I said / I’m just here to bring vengeance on somebody’s head.” This sounds like continuing a cycle of retribution, unless the vengeance is a matter of exposure, which some of the song’s lines seem to do to those currently in power. The third and final repetition, and the song’s last lines, have a Christological resonance that at once denies messianic pretensions and claims a place in the line of prophets, from Abel to Zechariah, who continue to speak from beyond the grave: “I ain’t no false prophet – No, I’m nobody’s bride / Can’t remember when I was born and I forgot when I died.” Another line, “I sing songs of love, I sing songs of betrayal”—the two options once victimage is seen, compassion for victims or exposure of wrong—could categorize hundreds of his other songs. My favorite couplet, no more reducible to a mimetic reading than any of the rest of the song, could be what Jesus was writing in the dust when he knelt with the woman caught in adultery in John 8. It’s what I wish I could say, at least to myself, when I see an accusatory look in someone else’s eyes: “What are you lookin’ at – there’s nothing to see / Just a cool breeze that’s encircling me.”

Publishing News

With this issue, we are also adding to the “Member Articles” section of the website another piece of cultural commentary through the lens of mimetic theory: Luke Nelson’s sharp analysis of the film Captain America: Civil War. We welcome comments on this piece as well as further commentaries of this sort, that is, neither reviews nor exhaustive academic articles, but analytical essays drawing on mimetic theory.

I recently received the two latest books on the way to all COV&R members from Michigan State University Press: Desire: Flaubert, Proust, Fitzgerald, Miller, Lana del Rey by Per Bjørnar Grande from the series Breakthroughs in Mimetic Theory and Oedipus; or, The Legend of a Conqueror by Marie Delcourt from Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture. The pandemic has often slowed down shipping but if your copies haven’t arrived in a few week, please email Bill Johnsen.

The 2020 issue of Contagion: Journal of Violence, Mimesis, and Culture, volume 27, has been published. For access, go to COV&R’s membership services site and follow the instructions. You can also access it on Project Muse or JSTOR if your library subscribes to those services.

Wolfgang Palaver’s online annotated bibliography, “René Girard” has been published in the series Oxford Bibliographies in Literary and Critical Theory. It includes 120 references, both primary and secondary, categorized by topic and discipline across the whole field of mimetic theory and can be updated regularly. It requires that your institution subscribe to this bibliography series. I think it is now the best place to start for a bibliographic introduction to the field.

Xiphias Gladius, the journal of the Spanish mimetic theory group, has put out a call for papers for a special issue on “Positive Mimesis: Education and Mimetic Theory.” The deadline for submissions is February 15, 2021. They are also planning a workshop on the same theme for November 19, 2020, at the University Francisco de Vitoria in Madrid.

Finally, we would like to ask for help in finding reviewers for some books that require special combinations of expertise: The Head Beneath the Altar: Hindu Mythology and the Critique of Sacrifice by Brian Collins and the first two volumes of Robert M. Doran’s projected three-volume series The Trinity in History: A Theology of the Divine Mission, Volume One: Missions and Processions and Volume Two: Missions, Relations, and Persons. If you would be interested, or if you know someone who might be willing and qualified, please contact our book review editor, Matthew Packer.

A St. Dominic’s Day Reflection on Pandemic and Apocalypse

James Alison

Madrid

February 2020 found me writing up a paper detailing some Girardian reflections on the Book of Revelation, based on workshops I had conducted in France. So when, in mid-March, we all began to get a sense of what was coming upon us, apocalyptic criteria were fresh in my mind. I had become aware of the two senses of the Apocalyptic, what I call the binary and the ternary. The binary includes all the oppositional realities involving death, fear, and destruction, frequently leading to projections onto God. And the ternary is the slow, quiet bringing into being of the New Creation in the midst of the winding down of all that violent futility. This is what John’s Apocalypse is all about: the bringing into being, by the lamb standing as one slain, of the New Creation, in the midst of the violent winding down of fake sacrality in the period leading up to the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple in 70 AD.

February 2020 found me writing up a paper detailing some Girardian reflections on the Book of Revelation, based on workshops I had conducted in France. So when, in mid-March, we all began to get a sense of what was coming upon us, apocalyptic criteria were fresh in my mind. I had become aware of the two senses of the Apocalyptic, what I call the binary and the ternary. The binary includes all the oppositional realities involving death, fear, and destruction, frequently leading to projections onto God. And the ternary is the slow, quiet bringing into being of the New Creation in the midst of the winding down of all that violent futility. This is what John’s Apocalypse is all about: the bringing into being, by the lamb standing as one slain, of the New Creation, in the midst of the violent winding down of fake sacrality in the period leading up to the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple in 70 AD.

Transferring this to COVID-19, I noticed how the social displacements following the arrival of the coronavirus, itself simply a thing that is, and maybe not even a thing that is alive, could be read in both binary and ternary modes of revelation. The first was obvious and came over us all with the closing down of activities, frontiers, public meeting places. The fear of death, and its heavy presence in Bergamo and Madrid. Then closer to wherever our home might be. The disarray among most Western governments, with leaders, especially in the UK, Brazil, and the US—three countries which are dear to me—being not only incompetent, but effectively sabotaging their own national efforts to provide resilience. Along with the blame displacement came the inevitable spin-off of conspiracy theories, leading to even more death. And finally, people flip-tricked into deadend madness concerning requests to wear face-masks, loudly proclaiming their loyalty to fake gods as they sputtered their way gravewards.

But then the gentler light of ternary revelation, as it becomes clearer what might, and might not be being brought into being as we begin to react. It becomes clear that the world of “fake news” wasn’t a passing matter, but rather that the portions of our governing class that hold power are imaginatively incapable of thinking of governance or any sort of common good. For them holding power is a public relations exercise enabling them more efficiently to feed off what for them was nothing other than the carcass of the state, finding short term ways to make more private money off public misfortune. Hence the epic mishandling of the production of medical material by private companies run by friends and cronies. Hence the refusal to use our countries’ respective central powers to shore up a resilient state for the benefit of all. Their economicist free-market gods simply wouldn’t allow them to do that, but instead demand sacrifice. This entire governing class has been corrupted over time by an entirely parasitic notion of the good: how can we profit from this situation, take advantage of what’s there while we may, the future be damned? This rather than an organic approach: learning to appreciate what is there and making it better, more efficient and more functional for all—what used to be called (almost too long ago to remember) “conservatism.” The gentler light, of that which is coming into being, makes clear what we need going forward, as we learn to cope rationally with these dangerous interactions with little understood created matter, in order to build resilience. Even as, at the same time, the flip side of the same light lays bare the terrible mental consequences of those who have been driven mad by their false gods.

It was as I watched the desperate clinging on to these gods that I wondered what underlies our addiction to fake goodness, this weddedness to oppositional identities and the rewards of parasitical prowess. So much seems linked to false understandings of redemption that are alive and well in the deep culture of the Anglosphere at least, and maybe well beyond it. If your understanding of how Christ saved you was that your radically depraved former nature has been juridically forgiven, covered over by a righteousness God imputes to you, so that you now have assurance of salvation, then of course why be concerned with the world that is passing out of existence, purely a place of sin? This only needs to be slightly secularized and you have the self-righteousness of profiteers feeding off what they consider a carcass. The self-righteousness is purely oppositional, purely dialectical, with culture war serving as the basis for identity in those who have pre-empted God’s justice in their lives. The popularity of that sort of evangelical faith among the neo-liberal elite, the complacent marriage of Friedman and the Presidential Prayer Breakfasts, seems quite coherent.

Lest anyone think that I am making some anti-Evangelical point here, I remind you that the Reformation’s personal assurance of salvation is, as I was taught by the theologian Joseph Ratzinger, merely the application to the modern individual of the much older and more collective assurance of salvation of the medieval Church. That “societas perfecta” now stands revealed as no more than a carapace of righteousness held to by the clerical caste. The collective self-righteousness of the Catholic hierarchy, creating and waging oppositional culture wars in order to sustain their illusion of an assuredly “saved” canonical figment, is scarcely different in its cultural effects from the Reformed variety: within a week of each other, both Franklin Graham and Cardinal Dolan had laid their “flocks” squarely at the feet of their “Chosen One.”

What is to be the shape of the Christian future as we let go of our addiction to these forms of fake goodness? The Ternary—in Christian understanding, the Spirit bringing creation into being “in between”—shows more and more clearly the way things work in between us, how we are in ever more visibly non-total membership of groupings we have taken for granted, so that our relations with them and with each other have constantly to be renegotiated. Yet at the same time we are shown where we may take responsibility, gifted with grace ourselves to be built up as we engage in the process of rebuilding for others.

Given what we have learned from René Girard, might we not start, amidst our growing awareness of the failure of the gods, with what I call the mimetics of shame? That is the way, independent of political or partisan belonging, in which un-recognised shame is triggering us into grasping onto fake forms of goodness, which means mimetically triggering each other into both subtle and caricatural forms of violence against each other. Might we begin to understand how we haven’t allowed Christ close to us if we have not allowed him to come tenderly into our shame and de-toxify it? For so much of what we’ve seen on both sides of the Atlantic has been a desperately aggrieved, reactive pride masking an un-admittable shame—individual, collective, sacred and secularised. And to learn to set each other free from the power of this shame requires an awareness of the One who is coming into our midst, gently undoing our shamed belonging. We are receiving hints like the hermeneutic of 1619—boosted by the New York Times project proposing that date—along with the far greater sense of penitence seen in hugely white participation in BLM, hints like the glimpses of Irish sanity in the face of English madness: the first signs that forgiveness for the sin of the Atlantic Slave Trade, for our self-righteous imperial adventures, is coming alive in our midst; and we may yet be given the chance to retrieve our minds from their corruption into self-defeating madness.

Writing an Afterword on Pandemics

Berry Vorstenbosch

Dutch Girard Society

In January 2020 I finished the Dutch text of a book on psychosis and mimetic theory (the title will be De overtocht—Filosofische blik op een psychose which translates as The Crossing—A Philosophical View on Psychosis). In order to make the reader familiar with mimetic theory, I leaned heavily on the metaphor of the epidemic, focusing on Girard’s treatment of Raskolnikov’s dream in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment as discussed in Girard’s Le Mensonge Romantique et la Vérité Romanesque (1961) and “The Plague in Literature and Myth” (1974). It is this essay, published in To Double Business Bound (1978), I took as the main text for explaining the relationship between Girard’s psychological theorem on mimetic desire and his anthropological theorem on the scapegoat mechanism.

In January 2020 I finished the Dutch text of a book on psychosis and mimetic theory (the title will be De overtocht—Filosofische blik op een psychose which translates as The Crossing—A Philosophical View on Psychosis). In order to make the reader familiar with mimetic theory, I leaned heavily on the metaphor of the epidemic, focusing on Girard’s treatment of Raskolnikov’s dream in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment as discussed in Girard’s Le Mensonge Romantique et la Vérité Romanesque (1961) and “The Plague in Literature and Myth” (1974). It is this essay, published in To Double Business Bound (1978), I took as the main text for explaining the relationship between Girard’s psychological theorem on mimetic desire and his anthropological theorem on the scapegoat mechanism.

In this essay, Girard presents the contemporary age as a world in which epidemics are virtually absent: “Judging from the role of the plague in Western literature up to the present, this metaphor is endowed with an almost incredible vitality, in a world where the plague and epidemics in general have disappeared almost altogether” (138). In January I added a footnote, emphasizing that the essay was written as early as 1974, and that the world had not yet gone through the experience of AIDS, Ebola, or SARS, making Girard’s observation here somewhat outdated.

Then, at the end of March we were in the lockdown. I felt obliged to rewrite the paragraphs in the main text in which I introduce this essay, referring explicitly to the coronavirus. In the Dutch Girard Society, we discussed this essay in a zoom session on April 10th. In May I added an afterword focusing on the pandemic. At that moment I felt I was not at all able to say something definitive about Covid-19. At the moment I write this notice, which is the first week of August, I will be approaching the last moment in which I can update my text before the book will go into print. I still sense my observations about the pandemic might become obsolete just within a couple of weeks.

The governing question in all my thoughts has been, from the beginning on: What type of crisis is this? With this question in mind, I do not mean to find a definite label for pinpointing the crisis. Rather, on the contrary, I want to pay attention to a certain fluidity I feel to be present in this crisis. One of the core insights in “The Plague in Literature and Myth” is that an epidemic, starting out as a medical crisis, as “just” a disease, may cross the barrier of the purely medical and evolve into a mimetic crisis. Girard manages to illustrate his idea with the help of a historical text which underlines the crossing of the border Girard wants to point at. It is worthwhile to quote the passage Girard cites from the French surgeon Ambroise Paré, writing in the 16th century:

At the outbreak of the plague, even the highest authorities are likely to flee, so that the administration of justice is rendered impossible and no one can obtain his rights. General anarchy and confusion then set in and that is the worst evil by which the commonwealth can be assailed: for that is the moment when the dissolute bring another and worse plague into the town (137, emphasis Girard’s).

The idea that one crisis in one area may affect other areas, and even can cause more severe crises in other areas, seemed to me highly insightful and relevant both to psychosis and Covid-19. Girard’s idea that the epidemic often functions as a metaphor for something even more serious, the “mimetic crisis” or the “sacrificial crisis,” is already present in Paré’s words. One crisis may trigger other crises, which, when they get enough momentum, can move beyond containment. Any crisis may theoretically degenerate into a full-blown sacrificial crisis, because mimesis, like viral contagion, runs according to the logic of a feedback-loop.

So here Girard is insightful. But Covid-19, as yet, at the end of July 2020, has not developed into a true mimetic crisis. The horrid scenario sketched by Ambroise Paré, of directly affecting the judiciary system and delivering societies to sheer chaos, nowhere materialized on a national, let alone larger scale. What we are dealing with in 2020 is far more complex than the two-crisis scheme—medical and mimetic—Girard employs in his essay.

We want to use the term “mimetic crisis” here as an equivalent of the term “sacrificial crisis,” that is, a crisis which threatens the community, the village—in our time this would be the “global village”—as a whole. Of course there have been all kinds of mimetic phenomena during Covid-19 so far, but something genuinely apocalyptic, resembling the threat of nuclear warfare—which is often, when referring to the present time, the socio-political paradigm in Girard’s thinking about the “mimetic crisis”—has not taken place.

As to Paré’s “general anarchy and confusion,” that is, as to crimes and misdemeanors, we can even say that during the lockdown in April crime rates have been drastically dropping in most countries. A good burglary is far more difficult to undertake when everybody is obliged to stay at home. Of course, the relationship between crime and the corona outbreak is very complex. Nevertheless, we have a pandemic which sometimes manages to produce effects which are the opposite of what Paré describes.

So, what type of crisis is this? Commentators have been writing about a social crisis, a political crisis, and, more frequently, about an economic crisis. Still there has been a reluctance to relabel this crisis as something predominantly social, political, or economic. Though the economic repercussions are already being strongly felt all over the world, Donald Trump’s tweet, made as early as March 23rd, that the coronavirus cure cannot “be worse than the problem itself,” is still controversial. Up till now the medical mindset seems to prevail in this crisis and the spike-studded virus seems to remain its icon.

Ambroise Paré’s words are, remarkably enough, not accurate for describing what is going on right now. A true 16th century epidemic threatening a whole town is not a model for describing the pandemic we are going through in the beginning of the 21st century. Then, there would have to be a sudden upscaling, a sudden acceleration with only one tipping point where a medical/humanitarian crisis turns into something genuinely world threatening. Up till now we have seen nothing of the sort.

Some members from our Society made the suggestion that the corona crisis should not be seen as a single, isolated crisis, but forms part of a larger pattern. We are living in the Anthropocene, and the way we damage our natural environment has its rebounds. The way we penetrate more and more deeply into the natural world, the way we travel around world, will all have their impact. Plagues have something in common with floods and earthquakes. They are not seen any more as inflictions from a potentially hostile “outside” world, as they still could be in the 16th century. We are living in a period where all kinds of crises may intersect and intermingle, and we may find all kinds of shifts from political to social or economic in any crisis.

I am still pondering the sentences I will have to write in my afterword before the deadline really closes. In a psychosis people often suffer from apocalyptic feelings. There is a whole chapter on this subject in Louis A. Sass’ Madness and Modernism entitled “World Catastrophe.” Yet, in the eyes of this writer, it is only the patients who suffer from those feelings. Girard, we know, takes apocalyptic feelings for real. One of the suggestions I would like to make in the afterword is that, in a truly big crisis the experience of “normal” people will get closer to the experience of people in a state of psychosis. But is this corona crisis already a truly big crisis? Yes, how big is it? Sometimes I feel I still don’t know.

Report on the 2020 COV&R Board Meeting

Martha Reineke, President

Nikolaus Wandinger, Executive Secretary

The Board held a digital meeting on July 8, 2020. In lieu of a business meeting this year, due to the postponement of our annual meeting until 2021, we are summarizing key features of the meeting here.

The Board voted to maintain the same board members given the inability of the membership to attend a business meeting at which a new slate of members could be approved. We truly appreciate the willingness of our current board members to extend their terms.

The Board received the report from the Ad Hoc Communications Committee tasked last year with making a recommendation to the Board about how to create and execute a communications/marketing strategy for COV&R that will support key goals. In discussions last year which the Board shared with the membership, we established this committee in order to facilitate developing the global potential for a robust mimetic theory network under the umbrella of COV&R. Additional goals include: growing the COV&R membership, increasing attendance at the annual meeting, enlarging book sales and author visibility, and raising attendance at regional events (in physical locations and on various digital platforms). After summarizing the meetings they held during the year, the committee recommended the hiring of a marketing specialist to develop a communications strategy to meet these goals.

After discussing this report, the board enthusiastically and unanimously voted to authorize a two-year contract ($20,000 per year) for a part-time Communications Content Director (See the “Letter from the President” in this Bulletin for more on this topic.) The position will be funded from membership dues and solicitations to private individuals and foundations. We plan to have updates on our funding outreach at the 2021 business meeting. It is anticipated that the position will evolve into a permanent, part-time position paid for by growth of membership in a Girard network and paid-content on the digital platform. A search committee was established to develop the position announcement, advertise for the position, interview candidates, and make a hiring recommendation to the Board. The committee will also develop benchmarks for the position. The second-year contract will be contingent on completion of first-year benchmarks. The committee has been asked to complete all work in order that the person can be hired by December 1, 2020.

Other important items on the agenda were: A discussion on whether the COV&R contribution at the AAR should be done online (strong voices for it), the reports on COV&R publications, where Bill Johnsen was able to tell us that finally Contagion was in the Web of Science. Bill also mentioned the latest books in the Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture Series. If anyone has not received their books, they should write to Bill. As the Imitatio grant that enables COV&R members to get those books free of charge runs out next year, the final free books will probably arrive in the fall of 2021. Hopefully the series can then live on its own.

COV&R membership was slightly down at the end of 2019, while it had risen the year before. We will have to see whether the postponement of the Purdue conference, which all on the Board agreed was a good decision, has any negative consequences for membership. On the other hand, the postponement had positive financial consequences, as the sum allocated to the conference was not spent and can be used next year. The treasurer also remarked that COV&R’s expenses for last year’s conference in Innsbruck were very modest.

Curtis suggested that he wanted to change the Bulletin to a more frequent format and estimated that it could be done without overburdening his schedule. He will try to bring more frequent updates. What is still difficult is finding reviewers. Some idea of how to improve that were discussed.

The Board also discussed creating a certificate for the winners of the Raymund Schwager Essay Contest. More on that topic can be read in Niki Wandinger’s “Musings of the Executive Secretary” in this Bulletin.

Forthcoming Events

COV&R at the American Academy of Religion

Online, November 29-December 10, 2020

Times and information on how to attend to be announced.

Session I: Beyond Scapegoats: Marginalized Voices in Conversation with René Girard

Convener and Moderator: Grant Kaplan, Saint Louis University

- Julia Robinson Moore (The University of North Carolina at Charlotte), “Mimetic Theory through the Voices of the Little Rock Nine: Black Scapegoats in the Desegregation of Central High School, 1957-1958.”

- Martha Reineke (University of Northern Iowa), “An Escalation to Extremes: Purity Spirals and Victimization.”

- Chelsea J. King (Sacred Heart University), “Girard, the Feminist? Bringing Mimetic Theory into Dialogue with Feminist Critiques of Sacrifice”

Session II: Mimetic Theory and Christian Spirituality

Convener: Grant Kaplan, Saint Louis University

Moderator: Brian Robinette, Boston College

- Jared Price (Multnomah Biblical Seminary), “‘All Shall Be Well’: Julian of Norwich, Rene Girard, Jacques Lacan, and the ‘Other Side’ of Christian Mysticism”

- Aline Lewis (Graduate Theological Union), “Mimetic Desire in Ignatius of Loyola’s Autobiography”

- Joseph Rivera (Dublin City University), “Eucharist as Contemplative Action: A Girardian Perspective”

Co-Sponsored Session with Nineteenth-Century Theology

Academic Rivalry in the Modern Age: Thinking with Girard and Beyond

Convener: Zachary Purvis

- Grant Kaplan (Saint Louis University), “Brothers or Enemies? Revisiting Academic Rivalry in the Möhler/Baur Debate”

- Bryan Wagoner (Davis and Elkins College), “Franz Overbeck and Carl Albert Bernouilli Through the Lens of Girardian Mimetic Rivalry”

Respondent: Johannes Zachhuber (University of Oxford)

Conference Reports

The Collaborators Conference

Finding Something Precious in the Interconnected Community

Dedicated to Mimetic Theory

Susan Wright

COV&R Board Member and former President of Theology & Peace

Twenty years ago I decided to attend my first COV&R conference, held that year at Boston College. Within minutes of arriving I bumped into Per Grande, who would become a future conference buddy and my dear friend. Following René Girard’s address, as I made my way to the reception, I bumped into Bob Hamerton-Kelly. He introduced me to René, who was very gracious. Over the course of the evening I enjoyed long conversations with Bob and others. I left in the wee hours, my head bursting with ideas and enthusiasm. It was the first of many conferences and late night conversations exploring the implications of mimetic theory.

Twenty years ago I decided to attend my first COV&R conference, held that year at Boston College. Within minutes of arriving I bumped into Per Grande, who would become a future conference buddy and my dear friend. Following René Girard’s address, as I made my way to the reception, I bumped into Bob Hamerton-Kelly. He introduced me to René, who was very gracious. Over the course of the evening I enjoyed long conversations with Bob and others. I left in the wee hours, my head bursting with ideas and enthusiasm. It was the first of many conferences and late night conversations exploring the implications of mimetic theory.

Two years earlier, I had registered for a course in New Testament at Syracuse University. It was there that I met Tony Bartlett and Jim Williams, my first teachers in Mimetic Theory. That simple decision would have a profound impact on my life. How easily it could have been otherwise!

That summer of 2000, having completed my first year at Colgate Rochester Crozier Divinity School, I had just written my first academic papers utilizing mimetic theory, one on the biblical prophets, another for a class in feminist theology. Returning to school inspired by my experience in Boston, I applied René’s texts to a wide range of paper topics from homosexuality and the Anglican Communion, to the sacrifice of Isaac, to Catherine Malabou’s theory of plasticity. For seven years I kept a blog, “No Outcasts.” Every post, whether exploring biblical texts, zombie movies, comics, or popular music, was an exciting exercise in discovering new insights born of mimetic theory. Twenty years of engagement with René’s ideas have confirmed his assertion that the theory asserts itself through the wide range of its application. I suspect many of you can attest to a similar experience.

What has surprised me, above and beyond the breadth of application of René’s original insights, is something that I now count as precious in part because it is all too rare. Over the course of these twenty years I have come to belong to a community that has formed around René’s legacy, a community that includes COV&R, Theology & Peace, Imitatio, Wood Hath Hope, the Raven Foundation, and Newborn Community of Faith—the cluster of groups and organizations that have personally touched my life. That cluster is part of a wider web of interconnected groups across the globe. I can’t think of a community of its kind anywhere. The diversity of applications of René’s thought has given rise to a diverse community that includes conservatives and liberals, people of faith and committed secularists, academics of every stripe and nationality, theologians, clergy, psychologists, school teachers, community activists…and more. COV&R and the larger network it has birthed is more than an academic association, more than an annual conference or online discussion platform. In addition to all this, the community that has formed around mimetic theory has loosed something else that is equally precious and far reaching.

Early in August, while attending the online Collaborators Conference presented by Theology & Peace and the Raven Foundation, I was struck by two things. First, the wide range of participants. In the Zoom chats I was thrilled to spot friends from Kansas City, Canada, and Australia. Then something profound happened. As I listened to Kevin Miller’s opening keynote, Rebecca Adams’s workshop, and David Dark’s presentation on the third day of the conference, I realized that deconstruction and reconstruction can occur simultaneously as a human community struggles to free itself from the negative effects of acquisitive mimesis, mimetic contagion, and sacrificial violence. To borrow Dark’s words: COV&R and the larger community dedicated to mimetic theory has become for me a “community of insight,…a holy resource of thinking through who we are in the world, how to dwell more righteously and thoughtfully within it.” Dark went on to describe the ways this insight, and the self-awareness it promotes, fosters a space, “a clearing for Beloved Community,” that welcomes people from every walk of life, each one coming to terms with their implication in sacrificial violence. Indeed, particular to the community dedicated to mimetic theory is that all our years of conversation, of wrestling with the applications of René’s thought, have, even beyond our various intentions, loosened the bonds of our denial. Understanding intellectually that we are all complicit in sacrificial violence allows us to release our fear and our denial, to become, as Dark says, more confessional. “Within this clearing I…have room for more personal admission in my own complicity in wrong-doing and in my own complicity to demonize others.” Rather than disavow my borrowing of others’ desire, I can, with humor and humility, admit it openly. We come “to see within ourselves the very animus, denial, fear that leads others to demonize.”

In this way the community that formed around mimetic theory cannot help but transcend the academic and theological frameworks through which it’s been articulated. Our long-term, collective engagement with the theory has equipped us with a sophisticated grammar for detecting the many forms of rivalry and collective violence. But lo and behold, this grammar, being self-reflexive, has been acting upon us, “deconstructing us and reconstructing us.” As Brian Robinette describes, I start catching myself in the act of imitation, the ways I’m scandalized.

After twenty years, I count myself very fortunate. I belong to a large extended family scattered across large territories, speaking many languages, from different social and religious contexts. Like most extended families, we disagree about politics, cultural issues, and the “correct” interpretation of René’s ideas. Sometimes we feud on Facebook. But we are atypical in one important respect: we possess a theory that is revolutionary in its implications, which gains relevance with every fresh interpretation. While we cannot escape our humanity, with all its beauty and fragility, and its predilection for violence, we have within our keeping the “infinite possibility,” as David Dark said, to witness to something novel—a human community, who, possessing the tools and the collective wisdom it has gathered over decades, and struggling with its own internal temptations to rivalry and scapegoating, has, intentionally or not, been expanding a space for Beloved Community.

When the Need is Urgent, Take it Slow:

Reflections on the Collaborators Conference

Suzanne Ross

Co-Founder of The Raven Foundation and COV&R Board Member

Many attendees at the Collaborators Conference for the Flourishing of Nonviolent Christianity in August were drawn to our community as a safe place to recover from the damaging effects of having been raised with a judgmental, punishing God. Presenters Kevin Miller, David Dark, and Audrey Assad spoke of their own journeys toward a more loving God and a more inclusive, merciful faith.

Many attendees at the Collaborators Conference for the Flourishing of Nonviolent Christianity in August were drawn to our community as a safe place to recover from the damaging effects of having been raised with a judgmental, punishing God. Presenters Kevin Miller, David Dark, and Audrey Assad spoke of their own journeys toward a more loving God and a more inclusive, merciful faith.

All our presenters encouraged us to imagine the impact Christian life and practice could have on the world if we strove to embody a God of mercy and love for people inside and outside church walls. Many of us are eager for that kind of change in our churches, and during a Q&A someone asked how we might leverage our impact by connecting with other communities and conferences doing similar work. Kevin Miller gave a provocative answer – bigger isn’t necessarily better, he said. Small can have an outsized impact; we can be the leaven in the dough if we have the patience to let the yeast do its thing.

Going Slow for Change

The theme of small and slow rippled through the talks. James Alison emphasized that the key element required to extend mercy to others is to recognize ourselves as also in need of forgiveness. This, he told us, is difficult and slow work because we may have to face our anger, resentments and deepest anxieties.

Audrey Assad graced us with a new song she calls “Mortal” in which she reflects on how hard but also how necessary it is to face our big, painful feelings. To introduce the song she said, “It’s hard to slow down enough to feel everything that we actually have going on in here.” She encouraged us to ask the deep, meaning of life questions even if we are afraid of the answers we might get. In the song she sings a question and her answer, “How does it feel to be mortal? Take it slow, now, take it slow.”

Why is going slow so necessary? Because without slowness we are reactive, and as Kevin warned we are at risk of simply rebuilding a new normal but with different people on the top and bottom. If we don’t go slow, we risk demonizing our opponents as we grasp after quick solutions to difficult problems. As David Dark reminded us, we risk losing sight of the humanity of people in impossible situations, such as policemen charged with carrying out orders or lose their jobs and fail to support their families.

Going Slow for Truth

It is easy to become impatient with slow because there is urgent work to do. Rahim Buford reminded us of the horrors of incarceration and of the need right now to protect poor people from being imprisoned because they cannot afford bail. Rahim offered us a model for alternative Christian community, one that ministers to the least and the last without conditions. He is a pastor of a church that has “left the building” as Julia Robinson Moore put it.

Julia encouraged us to take the time to learn the story of the Christian church’s complicity in racism and other forms of physical, spiritual, and emotional abuse. The point is not to find blame or punish ourselves. Shame cannot be part of this. But the only way to get the truth out into the open, Julia said, is to go slowly and take the time we need to dwell in the forgiveness offered by Christ.

Going Slow for Love

Taking it slow means being patient as we discover new ways to worship together and apart and taking risks like Adam Ericksen is doing to see what may be emerging now. It means learning how to desire the flourishing of ourselves and others, as Rebecca Adams explained. Rebecca told us that God desires our subjectivity, in other words, our flourishing and our freedom. God is therefore both close to us but not completely one with us so that who we are can emerge. That is the essence of love: generally desiring someone else’s freedom.

If we desire the flourishing of another we must begin with humility, in admitting that only the other holds the answer to what their flourishing might look like and that their flourishing will include ours. Interestingly from the mimetic perspective, Rebecca said that by imitating God’s desire for our flourishing, something new will emerge that we have not yet imagined possible.

Nonviolent Christianity is about going slow in the service of urgent needs so that real progress is possible, so authentic differences can emerge and be celebrated. I think that even God doesn’t know what the future holds because human beings like you and me, as wildly unpredictable as we are, have been included in the ongoing work of Creation. I truly believe that God is waiting to be surprised by the new forms of being human that we are in the midst of discovering.

If you missed the Collaborators Conference, you can still access the content! We are offering three different passes so you can join The Collaborators community:

- All-Access Pass: This pass gives you access to keynote, workshop, panel recordings, Audrey Assad’s concert performance, PLUS access to upcoming quarterly live workshops.

- Limited- Access: Keynotes & All Recordings: This pass gives you access to keynote, workshop, and panel recordings, plus Audrey Assad’s concert performance.

- Limited-Access Keynotes Only: This pass gives you access ONLY to keynote presentations and Audrey Assad’s concert performance.

Click here for more details and to purchase your pass!

Comments from Attendees

I believe that men like Rahim and others who have been incarcerated and are now getting out are leaven of the Kingdom of God in our society. We need to meet them, know them, welcome them and let them know that they have so much to teach us. Thank you, Rahim.

…

I will be dipping in and out of the presentations over the next month. Second times through one hears new things. Mostly, though, just so good to hear from thoughtful people trying to find the way to live into these dark times and bring forth love. So nice to be able to sustain connection despite the coronavirus. Thank you for all the effort that went in to making that possible. Here’s to meeting in the flesh next year!

…

Loved connecting with people across the globe that probably wouldn’t happen in person. But missed the “being with each other.”

…

Every opportunity to participate was a Highlight. It was a week of nurturing, seed spreading, and witness … so grateful to have been introduced to more amazing fellow “Becoming” siblings!

…

It was great to see Adam, Lindsey, and Suzanne in action after following them for awhile on video and podcast. I thought the workshops and keynotes were all top rate. Very thought provoking, a lot to ponder. Looking forward to upcoming workshops and presentations. As Lindsey and Suzanne say, I’m an aspiring Christian, and someone who wants to become a “former scapegoater”. Many thanks!

Book Reviews

For inquiries about writing a book review or submitting a book for review,

contact the book review editor, Matthew Packer.

Sophocles, Tragedy, Plague

William E. Cain

Wellesley College

Mark R. Anspach, ed. The Oedipus Casebook: Reading Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, with a new translation of Oedipus Tyrannus, by Wm. Blake Tyrrell. Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture Series. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. 2020. Pages xiv + 459.

Expertly edited by Mark R. Anspach, The Oedipus Casebook: Reading Sophocles’ Oedipus the King is an important contribution to the study of one of the greatest tragic dramas in the Western canon. It is an excellent resource for scholars, teachers, and students, and it will become an essential point of reference for examining the primary text, Sophocles, Greek tragedy, myth, ritual, and sacrifice.

The first part of the Casebook is the play itself, the Greek original on the left-hand page and a new translation by Wm. Blake Tyrrell on the right. The translation is briskly paced and riveting, and is supplemented by cogent annotations. Next are three sections of reprinted essays and excerpts from books, keyed to The Ritual Background, King and Victim, and Oedipus on Trial. The authors include, among others, Walter Burkert, René Girard, Terry Eagleton, Jan-Pierre Vernant, Michel Foucault, and Sandor Goodhart.

We are in the midst of a pandemic, and, in this context of suffering and death, Oedipus the King , c. 429-425 BCE, is all the more disturbingly resonant. It starts with the Priest’s report of a plague that is devastating Thebes:

The fever-bearing god,

A plague most hated, falls upon and strikes the city.

By him is the house of Cadmus emptied, and dark

Hades grows wealthy in wailing and lamentation. (27-30)

Sophocles has keenly in mind the plague that struck Athens in 430 BCE even as it was engaged in a wrenching conflict with Sparta. Perhaps a form of typhus, this plague came in waves for several years, killing as many as 100,000 people, one-third of the city-state’s population. Thucydides contracted the disease but survived—the great leader Pericles did not—and, in his History of the Peloponnesian War, he summarizes its effect on Athenian society: “The catastrophe was so overwhelming that men, not knowing what would happen next to them, became indifferent to every rule of religion or law.”

As David Mulroy has observed, “the play’s action begins with a plague that forces Oedipus to search for a sinner whose presence is polluting the city and angering the gods. There is no evidence that earlier versions of the story featured a plague. It is a detail that Sophocles invented for his dramatization of the story” (Sophocles: Oedipus Rex, 2011). Tyrrell conveys skillfully the scope and scale of the plague, but the Greek is more vivid and unnerving. As G. O. Hutchinson has said, Sophocles at the outset renders the plague “with immense descriptive power. A multiplicity of misfortunes, stressed with abundant anaphora and other devices, are presented as all occurring at this time together…. Present verbs given an urgent sense of a continuous situation now” (“Sophocles and Time,” Sophocles Revisited: Essays Presented to Sir Hugh Lloyd-Jones, ed. Jasper Griffin, 1999).

Memorable as this description is, given by the Priest and reinforced by the Chorus, the plague in Oedipus the King is perplexing: its wounds and ravages are forcibly evoked at the outset, yet it then disappears from the characters’ experiences and memories. Charles Segal makes exactly this point: “Even before the midpoint of the action, the plague is simply forgotten. Oedipus’ search for his origins completely overshadows the sufferings of the city that have set the plot in motion. We hear of the plague for the last time when Jocasta reproaches Oedipus and Creon for quarreling in private while ‘the land suffers from such a disease’” (Oedipus Tyrannus: Tragic Heroism and the Limits of Knowledge, 2nd ed., 2001).

In her stimulating essay in the Casebook, Helene Peter Foley calls attention to this curious feature of the ending and tries to explain it: “All members of the cast, both chorus and protagonists, are distracted from the plague that grips the city by their concern with the fate of Oedipus as destroyer of his own house” (319). As the play winds down, someone should remember the plague. No one does. This prompts Foley to place the blame on Creon: “He ignores the issue of the plague and expresses no sense of urgency about taking immediate action” (319). But it is not Creon who ignores the plague. It is Sophocles who does, deliberately.

“Oedipus promises to solve the mystery and end the plague,” says the scholar-translator Robert Bagg: “He begins a passionate inquest which reveals, when all the facts finally fit together, that it is Oedipus himself who has caused the plague. It is he who is polluting Thebes with his presence: a man who has killed his father and incestuously loved his mother” (Oedipus the King, trans. 1982). But the facts do not fit together, nor are they clear. The main elements of the plot are the plague, the murder of Laïos, the parentage of Oedipus. These are connected, or seem to be, but, in the text itself, the fit, the relationship among them is not precisely defined and articulated.

What Sophocles does is akin to a technique that Stephen Greenblatt has identified in Shakespearean drama:

Shakespeare found that he could immeasurably deepen the effect of his plays, that he could provoke in the audience and in himself a peculiarly passionate intensity of response, if he took out a key explanatory element, thereby occluding the rationale, motivation, or ethical principle that accounted for the action that was to unfold. The principle was not the making of a riddle to be solved, but the creation of a strategic opacity. This opacity, Shakespeare found, released an enormous energy that had been at least partially blocked or contained by familiar, reassuring explanations. (Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, 2004)

In his Oedipus, c. 55 CE, Seneca handles the ending differently. Jocasta, on stage, stabs herself to death with a sword, and the blinded Oedipus says:

All you with bodies burdened by disease

and fighting for your lives, I leave this place.

Look up! For even as I move away,

a gentler spirit animates the sky.

Whoever at death’s door somehow lives on,

let him now gulp great draughts of oxygen.

Go offer hope to those resigned to die;

the pestilence leaves Thebes along with me.

Destructive Fates and sickness’ trembling fear,

wasting, black plague, dementia—come here,

be my companions! All to me are dear. (trans. Rachel Hadas)

The plague will cease because Oedipus, who precipitated it, is departing from the city.

The ending is similar in Voltaire’s Oedipe, 1718. Oedipus has blinded himself; Jocasta is alive, soon to take her own life. The High Priest speaks:

A happy calm is warding off the storms

A most serene sun is rising above your heads.

Contagious fires are no longer lit.

Your tombs which were opening are already shut.

Death is fleeing and the god of heaven and earth

Is announcing his blessings through the voice of thunder. (trans. Frank J. Morlock)

In contrast, in Sophocles’ Oedipus the King the plague might or might not end. There is no mention of it one way or the other.

Through reports from the outside, and recollections from Jocasta, Oedipus has learned about his origins. But has it been proven that he killed Laïos? He might have—he thinks he did. On the other hand: the evidence is more in his mind than it is in the text. John Jones states that Tiresias functions as the authority we should rely on: he is “a prophet; he speaks for the god and his words disclose the hard bedrock truth of the situation” (On Aristotle and Greek Tragedy, 1962). But Sophocles does not reveal “the hard bedrock truth.” The other characters are seeking to establish it and believe that they do, and, as readers and theater-goers, we do versions of the same. We know the myth of Oedipus and import this configuration of relationships into the text so that the action of the play confirms it. But Sophocles gives no definitive answers to the questions he raises. I am reminded of Roland Barthes’s reference, in an essay on Michel Foucault, to “une question cathartique posée au savoir, à tout le savoir.”

From this perspective, the most provocative essays in the Casebook are by Girard, Goodhart, Anspach, and Frederick Ahl. For Girard—who analyzed the Oedipus myth and play on a number of occasions—Sophocles’ text is a deep exploration of mimetic rivalry and scapegoating:

The only distinction between Oedipus and his adversaries is that Oedipus initiates the contest, triggering the tragic plot. He thus has a certain head start on the others. But though the action does not occur simultaneously, its symmetry is absolute…. At first, each of the protagonists believes that he can quell the violence; at the end each succumbs to it. All are drawn unwittingly into the structure of violent reciprocity—which they always think they are outside of, because they all initially come from the outside and mistake this positional and temporary advantage for a permanent and fundamental superiority. (246-247)

Ultimately, according to Girard, “Oedipus fails to fix the blame on Creon or Tiresias. Creon and Tiresias are successful in their efforts to fix the blame on him. The entire investigation is a feverish hunt for a scapegoat, which finally turns against the very man who first loosed the hounds” (256).

The person who indicts Oedipus most harshly (and luridly) is Oedipus himself. As Anspach astutely comments, “not only does Oedipus accept without question that he has married his mother, he instantly assumes that he has murdered his father as well” (236). Someone must be guilty, and all converge on Oedipus—a remorseless enactment of scapegoating that he takes part in. He is determined to know the truth and concludes he has found it. But, as Ahl indicates, his truth may not be the truth. Like others, he hears what he wants to hear (427).

In the accounts of Laïos’ death, there is a potent ambiguity. Was the crime perpetrated by one man or many, by a murderer or murderers? (See lines 99-149, 292-293, 308, 715-716, 842-854.) “What is striking,” Goodhart contends, “is not only that Oedipus may not be the murderer of Laïos, but that there is a curious insistence in the play that the murderers of Laïos may be many” (399). “Rather than an illustration of the myth,” he maintains, “the play is a critique of mythogenesis, an examination of the process by which one arbitrary fiction comes to assume the value of truth” (412; Anspach, 239).

The essays by Girard and the others are compelling. But they falter in a crucial respect. Each implies or declares outright that Oedipus is not guilty. This is what Girard’s insights into religion and culture require—the victim of scapegoating is innocent. As he has argued elsewhere, New Testament revelation brings to light the truth behind Greek myth: “Le récit évangélique refute non seulement la culpabilité de Jesus mais tous les mensonges du même genre, par exemple celui qui fait d’Oedipe un donneur de peste parricide et incestueux” (Quand ses choses commerceront, 1994). But Sophocles does not present this conclusion, and, when we voice it, we are making a judgment that in its speed and certainty resembles the one that Oedipus propounds and clings to. We affirm his innocence; he affirms his guilt. As for Sophocles: he is, intentionally, non-committal.

Perhaps there were many murderers or bandits. Perhaps there was only one. Or, the murderer may be the man among the many who did the actual killing. Oedipus could not be the killer, but he could be. Scapegoats are innocent, except when they are not.

There is another complication that Girard overlooks, and it is expressed in the first words that Oedipus speaks, in his opening address to the afflicted of Thebes: “I have come myself, / Oedipus, called renowned in the estimation of all” (lines 7-8). In these lines, rivalry is not between two persons, as Girard’s classic formulation posits, but between Oedipus and himself—that is, the accomplished and acclaimed person he is and his own conception of the person he must become in the future. Being the renowned Oedipus fills him with pride but is a burden to him too: the person he has to imitate and transcend is himself.

The Priest praises Oedipus as “most powerful in the estimation of all” (line 40). Tyrrell’s repeated “estimation” shows the mirroring of Oedipus’s eminent sense of who he is and the identity by which others celebrate his uniqueness. He triumphed over the monstrous Sphinx, solving the riddle: “What walks on four feet in the morning, two in the afternoon and three at night?” He thereby liberated Thebes, was honored with the kingship, and received Jocasta’s hand in marriage. The Priest says to him: “Come, best of mortals, restore the city again” (line 46). Oedipus’s mimetic competitor is himself. This is his desire and predicament, a maddening one.

Oedipus must be as good or better than the man he became and is. As the action unfolds, this demand on himself, which he generates from his awareness of how he is seen by others, grows intolerable. What Oedipus does, is to resolve this crisis by avowing—before all of the evidence is in, and before it can be sifted through and scrutinized—that he has done the dreadful deeds. Everyone agrees to this, as they should not but as they must. As Girard says, “the firm conviction of the group is based on no other evidence than the unshakable unanimity of its own illogic” (257).

In his essay in the Casebook on scapegoat rituals in ancient Greece, Jan Bremmer tells us that in the myths he has assembled and explicated, the scapegoats “spontaneously” offer themselves: “Such behavior is the rule…. The victims always sacrifice themselves voluntarily” (173). This is the choice, paradoxically fated and free, that Oedipus makes. At once, he is Oedipus, the rival, and the scapegoat, the one who is sinfully different and who therefore must be excluded.

Oedipus, infamous, soon will be exiled. He merits this punishment because he is, he asserts, “most hateful to the gods.” He piercingly states the sentence that Creon should impose: “Send me abroad, away from here” (line 1521). But “most hateful” means singularity, prestige and renown as well as shame. For “my ills, my misfortunes / no man except me can bear” (lines 1414-1415).

In Oedipus at Colonus, Oedipus is extolled for his gift of prophecy, and, we are informed, he died a death nearly divine:

It was some messenger

sent by the gods, or some power of the dead

split open the fundament of earth, with good will,

to give him painless entry. He was sent on his way

with no accompaniment of tears, no pain of sickness;

if any man ended miraculously,

this man did. (lines 1883-1889, trans. David Grene)

This is the man who, at the close of Oedipus the King, had resolved the mimetic crisis he embodied by embracing his guilt for crimes he may or may not have committed. He blinds himself. We cannot take our eyes off him.

Towards Reconciliation

William A. Johnsen

Michigan State University

Paul Gifford, Towards Reconciliation: Understanding Violence and the Sacred after René Girard. Cambridge, UK: James Clarke & Company, 2020. Pages xiv + 148.

Paul Gifford, Towards Reconciliation: Understanding Violence and the Sacred after René Girard. Cambridge, UK: James Clarke & Company, 2020. Pages xiv + 148.

As an editor I appreciate and approve of Paul Gifford’s prose. When his train leaves the station the cars are full. I like that. This book based on a public lecture series is something I didn’t know he was good at, a hybrid now after revision, yet still a very attractive bringing back to the page of what was clearly and eloquently spoken. You can still hear him speaking. (James Clarke & Company should record him or podcast him.)

Yet there are also wonderful examples of “Gifford I” throughout: “Christianity is not—save at first sight, according to a misleading generic taxonomy and/or by convention—‘a religion’ (i.e. one among others). Nor is it ‘the religion’ (i.e. the only one—since ‘religion’ comes in thousands of varieties). Nor is it, either, ‘no kind of religion’ (a ‘faith’ but not a religion, for instance). It is, or it is nothing, the religion and faith, conjoined and interdependent, of the Gospel” (60; Bob Hamerton-Kelly would have loved that).

This is not a book aimed directly at scholars in the sense of being written to persuade scholars first, trickling down to the ordinary (ordinatus) reader. Gifford’s immediate audience is the community of Coventry Cathedral. He lightly chaffs his local audience when he says that England missed the boat on Girard. This slightly disparaging manner is the way the English talk to each other, an attractive modesty, but not to be taken literally (especially if you are not English). This is all good English fun onsite, but reading it in a book, this English professor from the colonies must stress what Gifford acknowledges elsewhere but does not say here (endnote 1), that Pierpaolo Antonello and Harald Wydra at Cambridge have been writing about and teaching mimetic theory for years; Michael Kirwan for an equally long period while at Heythrop, publishing two important books on Girard, conducting day-to-day teaching and advising of English and international students, offering conferences at Heythrop towards the reconciliation of separate religious communities through mimetic theory, commemorated in several volumes of collected essays, and sponsoring a well-attended COV&R conference at St. Mary’s University College at Strawberry Hill co-hosted by Heythrop in 2009. In the north of Ireland the influence of Roel Kaptein and Duncan Morrow has been immense. I will just mention the emerging and important work of Antonio Cerella and Elisabetta Brighi and then stop well short of a proper roll call, saving this (note to self) for someone’s future Contagion bibliographical essay on Girard in the UK.

So when Gifford says early on while discussing the influence of Girard’s Violence and the Sacred, that no one else was talking about the sacred and violence, he is getting to his subject as fast as he can, drawing on one of Schwager and Girard’s (and Chantre’s) special distinctions, the difference between the sacred (archaic violence) and the holy. If you ask at the library reference desk for “violence and religion” instead you will be deluged with articles, books, conferences and internet discussions from all over the planet, including of course countless episodes where Girard was asked if religion was violent. Bring several tote bags to the counter.

In the first four chapters, Gifford is headed towards how mimetic theory can prepare for reconciliation, a key responsibility at Coventry and, to adapt Yeats’s phrase, the most difficult of all work not impossible.

To get there Gifford and the rest of us are always obliged to fashion a working model of mimetic theory in order to launch our own work, so it is good to watch someone else build their model, and very relaxing to have someone take the wheel for us. More importantly, while Gifford is driving we can move our thoughts more productively around his model and ours.

The price of models (and live audiences) is condensation at the expense of complex understanding: to say that communities “invent” sacrifice by “choosing” scapegoats, and neatly “polarizing” off them, all efficiently, “automatically” lined up against (the last) one, can be misleading.

Presenting the scapegoat mechanism as a “self-regulating” mechanism (as we often do, see pages 36-37 and following) probably owes its origin to Des choses cachées of 1978 being directly followed by the prodigious collocation of scientists called in by Jean-Pierre Dupuy for the Disorder/Order conference at Stanford in 1981. “Self-regulating” derives from association to first and second order cybernetics, Varela and autopoiesis, fashioned to free one from needing to find a first cause or causer of the order emerging from disorder. But the danger of tagging the scapegoat mechanism as invention, as self-regulating mechanism, is to think that it works by itself, and there is no reason to think it won’t always work by itself.

And “invented” emphasizes awareness and consciousness too much, the matching of a recognized problem with its solution, like the older, earlier half of Prigogine and Stenger’s “nouveau alliance” for science—the world of classical physics, of causes and reversible forces. Paradoxically, the scapegoat mechanism is better understood through the newer science of the new alliance inaugurated in thermodynamics of irreversible processes, of entropy, and where discoveries are usually made when looking for something else.

Girard’s later favoring of the idea of a nondeterministic mechanism, especially in Evolution and Conversion, leaves room for human error and failure on both ends: that hominids will mostly destroy themselves when the foraging or hunting group gets too big (I put foraging before hunting, thinking that cooperation/sharing must be learned there first), that conflict will more likely break a group apart into smaller surviving groups alienated from each other, that violence might stop at a fifty-fifty stand-off (thus creating the dual systems Simon Simonse discusses), but only the very lucky group will hit on the efficacious misunderstanding of all united against the (last) one. And yet more luck is needed to repeat it accurately with the necessary misunderstanding.

As Gifford gets closer to his endpoint of reconciliation, he can only describe what and how he hopes confronting sides will learn from mimetic theory to find peace. COV&R members and speakers involved directly in peacemaking and reconciliation such as Duncan Morrow, Simon Simonse, and Vern Redekop caution that the closer you get to the scene of contention, the more modest your theorizing must be. Although Gifford chastises workers on the ground, at the trowel’s edge at Çatalhöyük and Göbekli Tepe for disrespecting (his) theorizing (endnote 2), the closer you get (I spent two weeks there), the more modest you become about theory.

COV&R members proselytize, no apologies for that. But how, exactly, do you spread the good of mimetic theory for greater appreciation and understanding? That’s been my job for 15 years at MSU Press and Imitatio, and I’m still not certain. Cynthia Haven’s book was reviewed expansively and positively in places we have not been before, and the effect has spread to other books in the series, especially Girard’s books and Wolfgang Palaver’s Rene Girard’s Mimetic Theory.

I believe (proudly) that somehow all of us are getting it done. Andreas Wilmes’s journal The Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence is both rigorous and exciting. The well-conceived series at Bloomsbury co-edited by Scott Cowdell, Chris Fleming, and Joel Hodge, is now established, and it looks to me like Gifford is starting something at James Clarke & Co (endnote 3). Good for him, good for them, good for all of us.

1 The meetings at Cambridge on Darwin and Girard are themselves examples of vital British interest in mimetic theory, and Wydra, Kirwan, Alison are of course present and included in the two volumes. In Gifford’s co-authored essay with Pierpaolo Antonello on Göbekli Tepe in Can We Survive Our Origins, a full set of pertinent references to the secondary literature is offered. In Towards Reconciliation Gifford cites only an article from The National Geographic on Göbekli Tepe. On my high horse I nevertheless read the article, which is very good and hearteningly solid, just the thing to refer to that his audience might have read themselves.

2 Gifford refers to the multiple authors (Clare, Dietrich, Gresky, Notroff, Peters and Pöllath) of “Ritual Practices and Conflict Mitigation at Early Neolithic Körtik Tepe and Göbekli Tepe, Upper Mesopotamia: A Mimetic Theoretical Approach” in Hodder, Violence and the Sacred in the Ancient Near East (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020) who take up his essay as “the review committee” (p. 56).